Crop Choice and Crop Rotations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sowing: Seed Drills and Planters

SOWING & ITS EQUIPMENT Seeding or sowing is an art of placing seeds in the soil to have good germination in the field. A perfect seeding gives a. Correct amount of seed per unit area. b. Correct depth at which seed is placed in the soil. c. Correct spacing between row-to-row and plant-to-plant. Sowing methods (i) Broadcasting Broadcasting is the process of random scattering of seed on the surface of seedbeds. It can be done manually or mechanically both. When broadcasting is done manually, uniformity of seed depends upon skill of the man. Soon after broadcasting the seeds are covered by planking or some other devices. Usually higher seed rate is obtained in this system. Mechanical broadcasters are used for large-scale work. This machine scatters the seeds on the surface of the seedbed at controlled rates. (ii) Dibbling Dibbling is the process of placing and seeds in holes made in seedbed and covering them. In this method, seeds are placed in holes make at definite depth at fixed spacing. The equipment used for dibbling is called dibbler. It is a conical instrument used to make proper holes in the field. Small hand dibblers are made with several conical projections made in a frame. This is very time consuming process, so it is not suitable for small seeds. Mostly vegetables are sown in this way. (iii) Drilling Drilling consists of dropping the seeds in furrow lines in a continuous flow and covering them with soil. Seed metering may be done either manually or mechanically. The number of rows planted may be one or more. -

Terminology for Integrated Resources Planning and Management

Terminology for Integrated Resources Planning and Management February 1998 compiled and edited by Keya Choudhury and Louisa J.M. Jansen Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Preface An integrated approach to the planning and management of land resources has been developed by FAO since its appointment as Task Manager for the implementation of Agenda 21/Chapter 10 (UN, 1992). The new approach emphasizes two main characteristics: - the active participation of stakeholders at national, provincial and local levels in the process of planning and decision making; and - the integration of technical, institutional, legal and socio-economic aspects. To achieve the implementation of land-use planning and land management cooperation among experts from the disciplines involved and integration of the respective results are required in order to identify and evaluate all biophysical, socio- economic and legal attributes of the land. The glossary aims to contribute to the development of a common technical language in land resources planning and management. The terms, methods and concepts used by the different sectors involved should be understood by all partners in an identical way, independent from their backgrounds and professional experiences. The terms and definitions which are included in this glossary encompass conservation and management of soil, (fresh-) water and vegetation; climate; farming systems; crop production, livestock and fish production; land tenure and sustainable development. The comments and suggestions received -

Design and Fabrication of Manually Operated Seed Sowing Machine

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 06 Issue: 06 | June 2019 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 DESIGN AND FABRICATION OF MANUALLY OPERATED SEED SOWING MACHINE R. Kathiravan1, P. Balashanmugam2 2Assistant professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Annamalai University, Tamilnadu, India (On Deputation) 1Lecturer (Part-time/Guest Lecturer) Department of Mechanical Engineering, Central Polytechnic College, Tharamani, Chennai-113, Tamilnadu, India ---------------------------------------------------------------------***---------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract This article addresses betterment in agricultural to stay alert for fighting to this problem by using different processes. Manually operated seed sowing machine consist of pesticides .pesticide spraying is one of the common mechanisms for sowing of the seed. This mechanism runs operations in agriculture field which requires lots of efforts simultaneously. The essential objective of sowing operation is to carry the pump in farm. It results in shoulder pain so to put the seed in desired depth and provide required spacing badly. This machine contains pesticide spraying too which between the seeds and cover the seeds with soil. We can make it multifunctional. This project addresses improvement achieve optimum yield by proper compaction over the seed in agriculture processes like sowing of seeds on ploughed and recommended row spacing. To meet the demands farmer land and distribution of fertilizer combinable by using have to use new techniques in cropping to increase the yield. mechanisms. Primarily this system works manually, but with The requirements of small scale sowing machines are, they lesser input energy requirement. should be simple in design, affordable for small scale peasant farmers, easy maintenance for effective handling by unskilled Seed sowing machine is a device which helps in the sowing farmers. -

A Review on Seed Sowing Method and Alternative Method for Small Farmers

International Journal of Research in Engineering, Science and Management 194 Volume-2, Issue-7, July-2019 www.ijresm.com | ISSN (Online): 2581-5792 A Review on Seed Sowing Method and Alternative Method for Small Farmers Ashish V. Kadu1, Vipul Rathod2, Vikram Matre3 1Professor, Dept. of Mechanical Engg., Prof. Ram Meghe Institute of Technology and Research, Amravati, India 2,3Student, Dept. of Mechanical Engg., Prof. Ram Meghe Institute of Technology and Research, Amravati, India Abstract: The majority of Indian Population is dependent on method, Seeds are dropped using a bamboo tube agriculture and contributes about 17-18%of India’s GDP. Sowing placed behind the plough. It requires time and seed is the first major process in agriculture. Manually sowing manpower. seed is not effective as the uniform spacing between consecutive 6. Transplanting: In this method, small seed lines are rows and plants cannot be maintained. Tractor aided seed drill is an effective way of sowing but is costly, not affordable, and made in the nursery, and this is planted in fields. requires high maintenance. This paper deals with the introduction A few years back, the use of tractor aided seed drills has of a seed sowing machine, which is easy to operate easy to maintain grown rapidly. It is an effective way of sowing, requires less can sow seeds in uniform spacing. It is made from scrap materials, time, but cost and maintenance is high. Farmers having less so it is cheap and available for small farms. The primary purpose agricultural land could not afford such high prices. So it of this paper is to study traditional ways of sowing seed and suggest becomes crucial to develop an alternative method of seed a machine to overcome limitations that we face in a traditional way of sowing seed. -

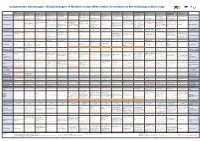

Rotation Chart

Comparative Advantages / Disadvantages of Rotation Crops With Cotton (in relation to the following cotton crop) COTTON SUMMER OILSEEDS SUMMER COARSE GRAINS SUMMER GRAIN LEGUMES WINTER PULSES GREEN MANURES PERENNIAL LEGUME WINTER OILSEEDS WINTER CEREALS BARE Wheat/Barley/ Cotton Sunflowers Soybeans Maize Sorghum Mung Beans Pigeon Peas Chickpeas Faba Beans Dolichos Lablab Vetch Lucerne Canola Safflower Long Fallow Triticale/Oats • Good cash crop. • Stubble breaks down easily. • Has role in cotton IPM as trap • Stubble breaks down easily. • Rarely if ever used as rotation • Low input crop. • Easy to grow cash crop. • Slow breakdown, very slow cycle • Stubble breaks down quickly. • Good stubble cover. • Long planting window. • Has role in cotton IPM as trap • Stubble breaks down quickly. • Has a role in IPM. • Efficient N fixer. • Can make cotton management • Poor stubble cover. • Good short - term cash crop. crop. • Does not aggravate cotton insect crop with cotton. • Improves soil structure. • Sowing time more aligned with of organic carbon. • Good gross margins. • Need corn front to harvest. • Has a role in IPM. crop. • Good cash crop. • Reduces N fertiliser for cotton. • Improves soil structure. more timely and easier . • Specialised harvest equipment. • Short season 90 days requires • Good cash crop. pests. • Good cash crop. • Can aggravate insect pests, cotton harvest. • Highly VAM dependent. • N - fixing legume. • Can aggravate cotton insect pests. • Stubble can be a problem. • Stubble breaks down quickly. • Good N fixer. • Reduces Black Root Rot. • Harbours beneficial insects. • Weed control is critical. General Overview • Can aggravate cotton insect pests. intensive management. • Stubble breaks down quickly. • Good N fixation. • Improve soil structure. -

Modeling and Manufacturing of Versatile Agriculture Machine

International Journal of Research in Engineering, IT and Social Science, ISSN 2250-0588, Impact Factor: 6.565, Volume 09, Special Issue 1, May 2019, Page 178-183 MODELING AND MANUFACTURING OF VERSATILE AGRICULTURE MACHINE K.MANOJ KUMAR REDDY 1 ,K.ASHOK2, K SAI JATHIN 3,M.PAVAN4,B SAI CHARAN5, 1Asst. Professor, 2345 B.Tech Students. Department of Mechanical Engineering,Narayana engineering college,Gudur-524101, India. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT food for three days will quarrel, for a week will fight and fora month or so will die‖. The paper aims on the design, Agriculture is a branch of applied science. development and the fabrication of the Agriculture is the science a and art of vehicle which can dig the soil, sow the farming including cultivating the soil, seeds, soil and pump to spray water .In producing crops and raising livestock. It is recent years the development of the the most important enterprise in the world. autonomous vehicles in the agriculture has Over the years, agricultural practices have experienced increased interest. In the field been carried out by small-holders cultivating of agricultural autonomous vehicle, a between 2 to 3 hectare, using human labor concept is been developed to investigate if and traditional tools such as wooden plough, multiple small autonomous machine could yoke, leveler, harrow, mallot, spade, big be more efficient than traditional large sikle etc. These tools are used in land tractors and human forces. preparation, for sowing of seeds, weeding Keeping the above ideology in mind, and harvesting. a unit with the following feature is designed, Modem agricultural techniques and Ploughing is one of the first steps in equipments are not used by small land farming. -

Study on Factors Affecting the Agricultural Mechanization Level in China Based on Structural Equation Modeling

sustainability Article Study on Factors Affecting the Agricultural Mechanization Level in China Based on Structural Equation Modeling Wei Li, Xipan Wei, Ruixiang Zhu and Kangquan Guo * College of Mechanical and Electronic Engineering, Northwest A&F University, Yangling 712100, China; [email protected] (W.L.); [email protected] (X.W.); [email protected] (R.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-159-2931-7953 Received: 1 November 2018; Accepted: 17 December 2018; Published: 21 December 2018 Abstract: The subsidy policy for the purchase of agricultural machinery and China’s Agricultural Mechanization Promotion Law have been implemented since 1998 and 2004, respectively. The goal of the policy and the law is to improve the agricultural mechanization level (AML) in China. Policymakers expect that the AML could be increased by improving the agricultural equipment level (AEL). The AML in China is affected by many factors. However, only a few studies have investigated the effects of the AEL on the AML. To fill this gap, we built an integrative conceptual framework and estimated a corresponding structural equation model (SEM) using the relevant data collected from 30 provinces (cities and districts) in mainland China. The relevant data cover the years from 2001 to 2014. There are six factors in our framework, including AEL, level of economic development, land resource endowment, benefit factors, policy and environmental factors, and demographic factors. The results showed that the AEL had the greatest impact on the AML. The level of economic development, the demographic factors, and the benefit factors not only directly affected China’s AML but also indirectly affected the AML through the AEL. -

A Beginning Farmer's Guide to Agriculture Words, Terms and Definitions

W 941 A Beginning Farmer’s Guide to Agriculture Words, Terms and Definitions A Beginning Farmer’s Guide to Agriculture Words, Terms and Defnitions l A Compiled by: Mitchell Mote, Extension Agent, Rutherford County Andrew P. Griffth, Associate Professor, Department of Agriculture and Resource Economics Kevin Rose, Extension County Director, Giles County Troy Dugger, Program Coordinator, Center for Proftable Agriculture INTRODUCTION This document is designed as a guide to help new or beginning farmers understand agriculture terminology. There are many terms related to different aspects of agriculture that may not be known to those who have not been involved in farming or have very little farming experience. Many of these terms and their meaning can be found in this document. While this list is not exhaustive of all the terms used in the feld of agriculture, it is prepared with the hope that the terms found in this guide will be useful and provide new and beginning farmers a foundation to better understand agriculture. How to “Talk” Farming Avian HOW TO TALK FARMING A beginning farmer's guide to Agriculture Words, Terms and Definitions Acidic: A soil pH of less than 7.0. The Apiary: A place where honeybees are Avian: Pertaining to poultry and/or fowl. lower the number, the more acidic the kept; colonies of bees in hives. soil will be. The pH scale ranges from Backgrounding: The feeding and 0 to 14, with 7 as neutral. Aquaculture: The commercial management of meat animals from production of aquatic plants or animals the time they are weaned as calves Acre: U.S. -

Glossary of Agronomic Terms (Martin Et Al

Glossary of Agronomic Terms (Martin et al. 1976) A Horizon The surface and subsurface soil that contains most of the organic matter and is subject to leaching. Abscission The natural separation of leaves, flowers, and fruits from the stems or other plant parts by the formation of a special layer of thin-walled cells. Acid soil A soil with a pH reaction of less than 7 (usually less than 6.6). An acid soil has a preponderance of hydrogen ions over hydroxyl ions. Litmus paper turns red in contact with most acid soils. Adventitious Arising from an unusual position on a stem or at the crown of a grass plant. Aerial roots Roots that arise from the stem above the ground. Aftermath The second or shorter growth of meadow plants in the same season after a hay or seed crop has been cut. Agrobiology A phase of the study of agronomy dealing with the relation of yield to the quantity of an added fertilizer element. Agronomy The science of crop production and soil management. The name is derived from the Greek words agros (field) and nomos (to manage). Aleurone The outer layer of cells of the endosperm of the seed. Alkali soil A soil, usually above pH 8.5, containing alkali salts in quantities that usually are deleterious to crop production. Alkaline soil A soil with a pH above 7, usually above pH 7.3. Ammonification The formation of ammonia or ammonium compounds in soils. Amylose The straight-chain fraction of normal starch. 106 Glossary of Agronomic terms Angiosperms The higher seed plants. -

Glossary of Precision Crop Management Terms Compiled for Use in Classroom Teaching by Dr

Glossary Of Precision Crop Management Terms Compiled For Use In Classroom Teaching by Dr. Bruce Erikson, Purdue University August 2017 Sources Glossary of forage terms, Purdue Extension (https://www.agry.purdue.edu/ext/forages/Forage%20Glossary-2010.pdf) A glossary of terms for precision farming, Purdue University, https://www.agriculture.purdue.edu/ssmc/frames/newglossery.htm Agriculture terms and definitions, Maryland Cooperative Extension, http://extension.umd.edu/sites/extension.umd.edu/files/_docs/Agriculture%20Terms2.pdf Precision agriculture seriee, timely information agriculture, natural resourse and forestry. Alabama Cooperative Extension system. https://sites.aces.edu/group/crops/precisionag/Publications/Timely%20Information/Introduction%2 0to%20Precision%20Ag%208-2010.pdf Important precision agriculture terminology, The Ohio State University, https://fabe.osu.edu/programs/precision-ag/other/precision-agriculture-terminology FAO Corporate Document Repository, Glossary of biotenology and Genetic Engineering, http://www.fao.org/docrep/003/X3910E/X3910E04.htm#TopOfPage FAO. 1983. Resolution 8/83 of the Twenty-second Session of the FAO Conference. Rome, 5-23 November 1983. FAO. 1999. The Global Strategy for the Management of Farm Animal Genetic Resources - Executive Brief. (see Glossary, pp. 39-42; the glossary was still evolving, but the draft definitions are those developed by the Panel of Experts assisting FAO to detail the Global Strategy.) USDA-DoA, Agricultural Biotechnology Glossary. https://www.usda.gov/topics/biotechnology/biotechnology-glossary Soil Science Society of America, Glossaruy of Soil Science Terms, https://www.soils.org/publications/soils-glossary Crop Science Society of America glossary of crop science terms, https://www.agronomy.org/publications/crops-glossary# P a g e 1 | 42 International Standard ISO 7256, Sowing equipment – Test Methods – Part 1: Single seed drills (precision drills) Ref. -

Winter Wheat Seedling Emergence from Deep Sowing Depths

CROPS Winter Wheat Seedling Emergence from Deep Sowing Depths William F. Schillinger,* Edwin Donaldson, Robert E. Allan, and Stephen S. Jones ABSTRACT sity (Rohde, 1966). By today's standards, it has poor Growers in low-precipitation (Ͻ300 mm annual) dryland wheat± disease resistance, modest yield potential, and inferior fallow areas of the inland Pacific Northwest need winter wheat (Triti- grain quality; it is also difficult to thresh, and has weak cum aestivum L.) cultivars that emerge from deep sowing depths in straw that causes lodging. Despite these deficiencies, dry soils. Stand establishment is the most important factor affecting Moro is the number-one club-type SWWW grown in winter wheat grain yield in this region. Despite poor resistance to Washington (Hasslen and McCall, 1995), due to its abil- disease, modest grain yield potential, and other problems, the out- ity to emerge from deep sowing depths through thick dated soft white winter wheat (SWWW) cultivar Moro is widely sown soil cover. in these dry areas, due to its excellent emergence ability. All other The climate of the inland Pacific Northwest is charac- SWWW cultivars are semidwarfs that carry emergence-impeding Rht 1 terized by winter precipitation and dry summers. Suc- or Rht2 reduced-height genes. From 12 sowing trials at 2 locations over 4 yr, we compared the emergence capability of Moro to (i) 8 cessful establishment of winter wheat on fallow in late SWWW cultivars and (ii) 16 SWWW advanced experimental Moro- August or early September is dependent on carryover replacement lines. Under both wet and dry soil conditions (soil water soil water from the previous winter. -

Modern Seed Sowing Techniques and Developing Technologies

International Journal of Innovative and Emerging Research in Engineering Volume 4, Issue 3, 2017 Available online at www.ijiere.com International Journal of Innovative and Emerging Research in Engineering e-ISSN: 2394 - 3343 p-ISSN: 2394 - 5494 Modern seed sowing techniques and developing technologies Pratik Hore.a, Goluprasad Gupta.a , Shrikrishn Deshmukh.a,Ashish Dhawale.a,Prof.S.S.Patil.b aB.E. Mechanical Engineering Department, ZCOER, Pune, Maharashtra, India bProf. Mechanical Engineering Department, ZCOER, Pune ,Maharashtra ,India ABSTRACT: India is an agricultural country because 75 % people work in the field. With increase in population, demand for the food is more than the supply. In order to bring down the demand supply gap sowing equipments are important for agriculture sector. Farmers normally complain about low yield growth from sowing seeds. For the growth of agriculture economy in India, mechanization is necessary. The main purpose of mechanization in agriculture is to improve the overall productivity & production. So many researchers work on different technologies in an agriculture sector to reduce human effort and increase crop production .This work helps to study as well as design & development of different techniques for seed sowing processes Keywords: Seed sowing process, techniques, design & development, seeding, labour I. INTRODUCTION Agriculture is the major occupation of the Indian rural people. Basically agriculture sector is the backbone of India’s sustained growth .Mostly, Farmers in India work in an agriculture field manually .Precision seeding reduces wastage of seeds and increase production rate. To increase precision seeding various industries are developing various automatic machines which reduce overall cycle time & cost of labor.