Amitiza and Linzess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gastrointestinal (GI) Motility, Chronic Therapeutic Class Review

Gastrointestinal (GI) Motility, Chronic Therapeutic Class Review (TCR) March 7, 2019 No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or via any information storage or retrieval system without the express written consent of Magellan Rx Management. All requests for permission should be mailed to: Magellan Rx Management Attention: Legal Department 6950 Columbia Gateway Drive Columbia, Maryland 21046 The materials contained herein represent the opinions of the collective authors and editors and should not be construed to be the official representation of any professional organization or group, any state Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee, any state Medicaid Agency, or any other clinical committee. This material is not intended to be relied upon as medical advice for specific medical cases and nothing contained herein should be relied upon by any patient, medical professional or layperson seeking information about a specific course of treatment for a specific medical condition. All readers of this material are responsible for independently obtaining medical advice and guidance from their own physician and/or other medical professional in regard to the best course of treatment for their specific medical condition. This publication, inclusive of all forms contained herein, is intended to be educational in nature and is intended to be used for informational purposes only. Send comments and suggestions to [email protected]. March 2019 Proprietary Information. Restricted Access – Do not disseminate or copy without approval. © 2004–2019 Magellan Rx Management. All Rights Reserved. FDA-APPROVED INDICATIONS Drug Manufacturer Indication(s) alosetron (Lotronex®)1 generic, . -

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Irritable Bowel Syndrome Similarities and Differences 2 www.ccfa.org IBD Help Center: 888.MY.GUT.PAIN 888.694.8872 Important Differences Between IBD and IBS Many diseases and conditions can affect the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which is part of the digestive system and includes the esophagus, stomach, small intestine and large intestine. These diseases and conditions include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). IBD Help Center: 888.MY.GUT.PAIN 888.694.8872 www.ccfa.org 3 Inflammatory bowel diseases are a group of inflammatory conditions in which the body’s own immune system attacks parts of the digestive system. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Inflammatory bowel diseases are a group of inflamma- Causes tory conditions in which the body’s own immune system attacks parts of the digestive system. The two most com- The exact cause of IBD remains unknown. Researchers mon inflammatory bowel diseases are Crohn’s disease believe that a combination of four factors lead to IBD: a (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). IBD affects as many as 1.4 genetic component, an environmental trigger, an imbal- million Americans, most of whom are diagnosed before ance of intestinal bacteria and an inappropriate reaction age 35. There is no cure for IBD but there are treatments to from the immune system. Immune cells normally protect reduce and control the symptoms of the disease. the body from infection, but in people with IBD, the immune system mistakes harmless substances in the CD and UC cause chronic inflammation of the GI tract. CD intestine for foreign substances and launches an attack, can affect any part of the GI tract, but frequently affects the resulting in inflammation. -

Therapeutic Class Overview Irritable Bowel Syndrome Agents

Therapeutic Class Overview Irritable Bowel Syndrome Agents Therapeutic Class Overview/Summary: This review will focus on agents used for the treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS).1-5 IBS is a gastrointestinal syndrome characterized primarily by non-specific chronic abdominal pain, usually described as a cramp-like sensation, and abnormal bowel habits, either constipation or diarrhea, in which there is no organic cause. Other common gastrointestinal symptoms may include gastroesophageal reflux, dysphagia, early satiety, intermittent dyspepsia and nausea. Patients may also experience a wide range of non-gastrointestinal symptoms. Some notable examples include sexual dysfunction, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, increased urinary frequency/urgency and fibromyalgia-like symptoms.6 IBS is defined by one of four subtypes. IBS with constipation (IBS-C) is the presence of hard or lumpy stools with ≥25% of bowel movements and loose or watery stools with <25% of bowel movements. When IBS is associated with diarrhea (IBS-D) loose or watery stools are present with ≥25% of bowel movements and hard or lumpy stools are present with <25% of bowel movements. Mixed IBS (IBS-M) is defined as the presence of hard or lumpy stools with ≥25% and loose or water stools with ≥25% of bowel movements. Final subtype, or unsubtyped, is all other cases of IBS that do not fall into the other classes. Pharmacological therapy for IBS depends on subtype.7 While several over-the-counter or off-label prescription agents are used for the treatment of IBS, there are currently only two agents approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of IBS-C and three agents approved by the FDA for IBS-D. -

United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,969,514 B2 Shailubhai (45) Date of Patent: Mar

USOO896.9514B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,969,514 B2 Shailubhai (45) Date of Patent: Mar. 3, 2015 (54) AGONISTS OF GUANYLATECYCLASE 5,879.656 A 3, 1999 Waldman USEFUL FOR THE TREATMENT OF 36; A 6. 3: Watts tal HYPERCHOLESTEROLEMIA, 6,060,037- W - A 5, 2000 Waldmlegand et al. ATHEROSCLEROSIS, CORONARY HEART 6,235,782 B1 5/2001 NEW et al. DISEASE, GALLSTONE, OBESITY AND 7,041,786 B2 * 5/2006 Shailubhai et al. ........... 530.317 OTHER CARDOVASCULAR DISEASES 2002fOO78683 A1 6/2002 Katayama et al. 2002/O12817.6 A1 9/2002 Forssmann et al. (75) Inventor: Kunwar Shailubhai, Audubon, PA (US) 2003,2002/0143015 OO73628 A1 10/20024, 2003 ShaubhaiFryburg et al. 2005, OO16244 A1 1/2005 H 11 (73) Assignee: Synergy Pharmaceuticals, Inc., New 2005, OO32684 A1 2/2005 Syer York, NY (US) 2005/0267.197 A1 12/2005 Berlin 2006, OO86653 A1 4, 2006 St. Germain (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 299;s: A. 299; NS et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2008/0137318 A1 6/2008 Rangarajetal.O U.S.C. 154(b) by 742 days. 2008. O151257 A1 6/2008 Yasuda et al. 2012/O196797 A1 8, 2012 Currie et al. (21) Appl. No.: 12/630,654 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (22) Filed: Dec. 3, 2009 DE 19744O27 4f1999 (65) Prior Publication Data WO WO-8805306 T 1988 WO WO99,26567 A1 6, 1999 US 2010/O152118A1 Jun. 17, 2010 WO WO-0 125266 A1 4, 2001 WO WO-02062369 A2 8, 2002 Related U.S. -

Amitiza (Lubiprostone) Capsule, 24 Mcg and 8 Mcg

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH Approval Package for: APPLICATION NUMBER: NDA 021908/S-010 Trade Name: AMITIZA Generic Name: Lubiprostonel Sponsor: Sucampo Pharma Americas, Inc. Approval Date: 11/26/2012 Indications: Amitiza is a chloride channel activator indicated for: Treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation in adults (1.1) Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation in women ≥ 18 years old (1.2) CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: NDA 021908/S-010 CONTENTS Reviews / Information Included in this NDA Review. Approval Letter X Other Action Letters Labeling X Summary Review Officer/Employee List Office Director Memo Cross Discipline Team Leader Review Medical Review(s) Chemistry Review(s) Environmental Assessment Pharmacology Review(s) X Statistical Review(s) Microbiology Review(s) Clinical Pharmacology/Biopharmaceutics Review(s) Risk Assessment and Risk Mitigation Review(s) Proprietary Name Review(s) Other Review(s) Administrative/Correspondence Document(s) X CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: NDA 021908/S-010 APPROVAL LETTER DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Food and Drug Administration Silver Spring MD 20993 NDA 21908/S-010 SUPPLEMENT APPROVAL Sucampo Pharma Americas, Inc. Attention: Jeff Carey Senior Director, Regulatory Affairs 4520 East-West Highway, Suite 300 Bethesda, Maryland 20814 Dear Mr. Carey: Please refer to your Supplemental New Drug Application (sNDA) dated and received March 7, 2012, submitted under section 505(b) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) for Amitiza (lubiprostone) Capsule, 24 mcg and 8 mcg. We acknowledge receipt of your amendment dated May 8, 2012. This Prior Approval supplemental new drug application provides for the following: • Removal of Section 5.1 Pregnancy • Revisions to Section 8.1 Pregnancy and Section 8.3 Nursing Mothers • Addition of Section 17.2 Nursing Mothers We have completed our review of this supplemental application, as amended. -

Identification of Pparγ Ligands with One-Dimensional Drug Profile Matching

Drug Design, Development and Therapy Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH Identification of PPARγ ligands with One-dimensional Drug Profile Matching Diána Kovács1 Introduction: Computational molecular database screening helps to decrease the time and Zoltán Simon2,3 resources needed for drug development. Reintroduction of generic drugs by second medical Péter Hári2,3 use patents also contributes to cheaper and faster drug development processes. We screened, András Málnási-Csizmadia2,4,5 in silico, the Food and Drug Administration-approved generic drug database by means of the Csaba Hegedűs6 One-dimensional Drug Profile Matching (oDPM) method in order to find potential peroxisome László Drimba1 proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) agonists. The PPARγ action of the selected generics was also investigated by in vitro and in vivo experiments. József Németh1 Materials and methods: The in silico oDPM method was used to determine the binding Réka Sári1 potency of 1,255 generics to 149 proteins collected. In vitro PPARγ activation was determined 1 Zoltán Szilvássy by measuring fatty acid-binding protein 4/adipocyte protein gene expression in a Mono Mac 1 Barna Peitl 6 cell line. The in vivo insulin sensitizing effect of the selected compound (nitazoxanide; 1Department of Pharmacology 50–200 mg/kg/day over 8 days; n = 8) was established in type 2 diabetic rats by hyperinsulinemic and Pharmacotherapy, University euglycemic glucose clamping. of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary; 2Drugmotif, Ltd, Veresegyház, Hungary; Results: After examining the closest neighbors of each of the reference set’s members and 3Printnet, Ltd, Budapest, Hungary; counting their most abundant neighbors, ten generic drugs were selected with oDPM. -

Lubiprostone Increases Small Intestinal Smooth Muscle Contractions Through a Prostaglandin E Receptor 1 (EP1)-Mediated Pathway

Lubiprostone Increases Small Intestinal Smooth Muscle Contractions Through a Prostaglandin E Receptor 1 (EP1)-mediated Pathway The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Chan, Walter W., and Hiroshi Mashimo. 2013. “Lubiprostone Increases Small Intestinal Smooth Muscle Contractions Through a Prostaglandin E Receptor 1 (EP1)-mediated Pathway.” Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility 19 (3): 312-318. doi:10.5056/ jnm.2013.19.3.312. http://dx.doi.org/10.5056/jnm.2013.19.3.312. Published Version doi:10.5056/jnm.2013.19.3.312 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11717596 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA J Neurogastroenterol Motil, Vol. 19 No. 3 July, 2013 pISSN: 2093-0879 eISSN: 2093-0887 http://dx.doi.org/10.5056/jnm.2013.19.3.312 Original Article JNM Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility Lubiprostone Increases Small Intestinal Smooth Muscle Contractions Through a Prostaglandin E Receptor 1 (EP1)-mediated Pathway Walter W Chan1,2 and Hiroshi Mashimo1,2,3* 1Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; 2Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; and 3Division of Gastroenterology, VA Boston Health System, Boston, MA, USA Background/Aims Lubiprostone, a chloride channel type 2 (ClC-2) activator, was thought to treat constipation by enhancing intestinal secretion. -

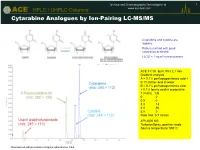

Cytarabine Analogues by Ion-Pairing LC-MS/MS

© Advanced Chromatography Technologies Ltd. 1 ® ACE HPLC / UHPLC Columns www.ace-hplc.com Cytarabine Analogues by Ion-Pairing LC-MS/MS Cytarabine and cytidine are isobaric. Robust method with good separation achieved. LLOQ = 1 ng/ml human plasma ACE 3 C18 3μm, 50 x 2.1 mm Gradient analysis A = 0.1% perfluoropentanoic acid + 0.1% formic acid in water B = 0.1% perfluoropentanoic acid + 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile T (mins) %B 0 0 0.5 0 3.0 13 4.0 90 5.0 0 Flow rate: 0.7 ml/min API 4000 MS TurboIonSpray, positive mode Source temperature: 550°C Reproduced with permission of Agilux Laboratories, USA © Advanced Chromatography Technologies Ltd. 2 ® ACE HPLC / UHPLC Columns www.ace-hplc.com Tricyclic Antidepressants Key: ACE Excel SuperC18 1 Doxepin 2μm, 100 x 3.0mm 1a Doxepin isomer Gradient analysis 1 Imipramine 3 A = 20 mM ammonium formate pH 3.0 2 Desipramine 3 Amitriptyline B = 20 mM ammonium formate pH 3.0 in MeOH:water 9:1 v/v 4 Nortriptyline 1 5 Clomipramine 2 Time (mins) %B 6 0 50 6 70 7 70 7.5 4 5 Flow rate: 1.2ml/min Column temperature: 40°C Injection volume: 2μl Detection: UV, 260nm 1a 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 min © Advanced Chromatography Technologies Ltd. 3 ® ACE HPLC / UHPLC Columns www.ace-hplc.com 15-Hydroxy Lubiprostone in Human Plasma Lubiprostone, a fatty acid derived from prostaglandin E1, is rapidly metabolised to 15-hydroxy lubiprostone. Quantitation is based on 15-hydroxy lubiprostone, with the d4 analogue as internal standard Lowest calibration standard sample containing 2.0pg/ml in human 15-Hydroxy lubiprostone EDTA K3 plasma MW 392.5 ACE Excel 2 C18 2μm, 50 x 3.0mm Isocratic analysis 15-Hydroxy I.S. -

Pharmaceuticals As Environmental Contaminants

PharmaceuticalsPharmaceuticals asas EnvironmentalEnvironmental Contaminants:Contaminants: anan OverviewOverview ofof thethe ScienceScience Christian G. Daughton, Ph.D. Chief, Environmental Chemistry Branch Environmental Sciences Division National Exposure Research Laboratory Office of Research and Development Environmental Protection Agency Las Vegas, Nevada 89119 [email protected] Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Why and how do drugs contaminate the environment? What might it all mean? How do we prevent it? Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada This talk presents only a cursory overview of some of the many science issues surrounding the topic of pharmaceuticals as environmental contaminants Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada A Clarification We sometimes loosely (but incorrectly) refer to drugs, medicines, medications, or pharmaceuticals as being the substances that contaminant the environment. The actual environmental contaminants, however, are the active pharmaceutical ingredients – APIs. These terms are all often used interchangeably Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Office of Research and Development Available: http://www.epa.gov/nerlesd1/chemistry/pharma/image/drawing.pdfNational -

Interactions with HBV Treatment

www.hep-druginteractions.org Interactions with HBV Treatment Charts revised September 2021. Full information available at www.hep-druginteractions.org Page 1 of 6 Please note that if a drug is not listed it cannot automatically be assumed it is safe to coadminister. ADV, Adefovir; ETV, Entecavir; LAM, Lamivudine; PEG IFN, Peginterferon; RBV, Ribavirin; TBV, Telbivudine; TAF, Tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, Tenofovir-DF. ADV ETV LAM PEG PEG RBV TBV TAF TDF ADV ETV LAM PEG PEG RBV TBV TAF TDF IFN IFN IFN IFN alfa-2a alfa-2b alfa-2a alfa-2b Anaesthetics & Muscle Relaxants Antibacterials (continued) Bupivacaine ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Cloxacillin ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Cisatracurium ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Dapsone ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Isoflurane ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Delamanid ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Ketamine ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Ertapenem ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Nitrous oxide ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Erythromycin ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Propofol ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Ethambutol ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Thiopental ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Flucloxacillin ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Tizanidine ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Gentamicin ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Analgesics Imipenem ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Aceclofenac ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Isoniazid ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Alfentanil ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Levofloxacin ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Aspirin ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Linezolid ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Buprenorphine ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Lymecycline ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Celecoxib ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Meropenem ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Codeine ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ for distribution. for Methenamine ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Dexketoprofen ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Metronidazole ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Dextropropoxyphene ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Moxifloxacin ◆ ◆ ◆ -

2015.09 IBS Drug Class Review.Pdf

Drug Class Review Agents Indicated in the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome 56:92 GI Drugs, Miscellaneous Alosetron (Lotronex®) Eluxadoline (Viberzi®) Linaclotide (Linzess®) Lubiprostone (Amitiza®) Tegaserod (Zelnorm®) Final Report September 2015 Review prepared by: Melissa Archer, PharmD, Clinical Pharmacist Irene Pan, PharmD Candidate 2016 Chelsey Hancock, PharmD Candidate 2016 Carin Steinvoort, PharmD, Clinical Pharmacist Gary Oderda, PharmD, MPH, Professor University of Utah College of Pharmacy Copyright © 2015 by University of Utah College of Pharmacy Salt Lake City, Utah. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 Table 1. Comparison of the Agents Indicated in the Treatment of IBS ................................. 5 Disease Overview ........................................................................................................................ 6 Table 2. Summary of IBS Treatment Options ........................................................................ 8 Table 3. IBS Disease Staging System .................................................................................... 11 Table 4. Most Current Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of IBS ..................... 13 Pharmacology .............................................................................................................................. -

OUH Formulary Approved for Use in Breast Surgery

Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Formulary FORMULARY (Y): the medicine can be used as per its licence. RESTRICTED FORMULARY (R): the medicine can be used as per the agreed restriction. NON-FORMULARY (NF): the medicine is not on the formulary and should not be used unless exceptional approval has been obtained from MMTC. UNLICENSED MEDICINE – RESTRICTED FORMULARY (UNR): the medicine is unlicensed and can be used as per the agreed restriction. SPECIAL MEDICINE – RESTRICTED FORMULARY (SR): the medicine is a “special” (unlicensed) and can be used as per the agreed restriction. EXTEMPORANEOUS PREPARATION – RESTRICTED FORMULARY (EXTR): the extemporaneous preparation (unlicensed) can be prepared and used as per the agreed restriction. UNLICENSED MEDICINE – NON-FORMULARY (UNNF): the medicine is unlicensed and is not on the formulary. It should not be used unless exceptional approval has been obtained from MMTC. SPECIAL MEDICINE – NON-FORMULARY (SNF): the medicine is a “special” (unlicensed) and is not on the formulary. It should not be used unless exceptional approval has been obtained from MMTC. EXTEMPORANEOUS PREPARATION – NON-FORMULARY (EXTNF): the extemporaneous preparation (unlicensed) cannot be prepared and used unless exceptional approval has been obtained from MMTC. CLINICAL TRIALS (C): the medicine is clinical trial material and is not for clinical use. NICE TECHNOLOGY APPRAISAL (NICETA): the medicine has received a positive appraisal from NICE. It will be available on the formulary from the day the Technology Appraisal is published. Prescribers who wish to treat patients who meet NICE criteria, will have access to these medicines from this date. However, these medicines will not be part of routine practice until a NICE TA Implementation Plan has been presented and approved by MMTC (when the drug will be given a Restricted formulary status).