Relationship Between Corals and Fishes on the Great Barrier Reef

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zoology Marine Ornamental Fish Biodiversity of West Bengal ABSTRACT

Research Paper Volume : 4 | Issue : 8 | Aug 2015 • ISSN No 2277 - 8179 Zoology Marine Ornamental Fish Biodiversity of KEYWORDS : Marine fish, ornamental, West Bengal diversity, West Bengal. Principal Scientist and Scientist-in-Charge, ICAR-Central Institute of Fisheries Education, Dr. B. K. Mahapatra Salt Lake City, Kolkata-700091, India Director and Vice-Chancellor, ICAR-Central Institute of Fisheries Education, Versova, Dr. W. S. Lakra Mumbai- 400 061, India ABSTRACT The State of West Bengal, India endowed with 158 km coast line for marine water resources with inshore, up-shore areas and continental shelf of Bay of Bengal form an important fishery resource and also possesses a rich wealth of indigenous marine ornamental fishes.The present study recorded a total of 113 marine ornamental fish species, belonging to 75 genera under 45 families and 10 orders.Order Perciformes is represented by a maximum of 26 families having 79 species under 49 genera followed by Tetraodontiformes (5 family; 9 genus and 10 species), Scorpaeniformes (2 family; 3 genus and 6 species), Anguilliformes (2 family; 3 genus and 4 species), Syngnathiformes (2 family; 3 genus and 3 species), Pleuronectiformes (2 family; 2 genus and 4 species), Siluriformes (2 family; 2 genus and 3 species), Beloniformes (2 family; 2 genus and 2 species), Lophiformes (1 family; 1 genus and 1 species), Beryciformes(1 family; 1 genus and 1 species). Introduction Table 1: List of Marine ornamental fishes of West Bengal Ornamental fishery, which started centuries back as a hobby, ORDER 1: PERCIFORMES has now started taking the shape of a multi-billion dollar in- dustry. -

Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 2017

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 CONTENTS VISION 3 NATIONAL PRIORITY CASE STUDY: SECURING 34 THE FUTURE OF THE GREAT BARRIER REEF MISSION 3 ARTICLE: THE GUARDIANS OF THE GREAT 36 AIMS 3 BARRIER REEF OVERVIEW 3 GRADUATE AND EARLY CAREER TRAINING 38 DIRECTOR’S REPORT 4 CAREER DEVELOPMENT AND ALUMNI 48 RESEARCH IMPACT AND ENGAGEMENT 6 GRADUATE PROFILE: DR VIVIAN LAM 51 RECOGNITION OF EXCELLENCE BY CENTRE 8 NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL LINKAGES 52 RESEARCHERS ARTICLE: CENTURIES-OLD NAUTICAL MAPS REVEAL 57 2017 HIGHLY CITED RESEARCHERS 9 CORAL LOSS MUCH WORSE THAN WE THOUGHT RESEARCH PROGRAM 1: 10 COMMUNICATION, MEDIA AND 58 PEOPLE AND ECOSYSTEMS PUBLIC OUTREACH PROGRAM LEADER PROFILE: 12 GOVERNANCE 62 ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR TIFFANY MORRISON MEMBERSHIP 65 RESEARCH PROGRAM 2: 18 ECOSYSTEM DYNAMICS: PAST, PRESENT PUBLICATIONS 68 AND FUTURE FINANCIAL STATEMENT 80 PROGRAM LEADER PROFILE: 20 DR VERENA SCHOEPF FINANCIAL OUTLOOK 81 RESEARCH PROGRAM 3: 26 2018 ACTIVITY PLAN 82 RESPONDING TO A CHANGING WORLD KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS 83 PROGRAM LEADER PROFILE: 28 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 87 ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR MAJA ADAMSKA ARTICLE: WHY SLIMY FISH LIPS ARE THE SECRET 33 TO EATING STINGING CORAL At the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies we acknowledge the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this nation. We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands and sea where we conduct our business. We pay our respects to ancestors and Elders, past, present and future. The ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies is committed to honouring Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ unique cultural and spiritual relationships to the land, waters and seas and their rich contribution to society. -

Effects of Eutrophication on Stream Ecosystems

EFFECTS OF EUTROPHICATION ON STREAM ECOSYSTEMS Lei Zheng, PhD and Michael J. Paul, PhD Tetra Tech, Inc. Abstract This paper describes the effects of nutrient enrichment on the structure and function of stream ecosystems. It starts with the currently well documented direct effects of nutrient enrichment on algal biomass and the resulting impacts on stream chemistry. The paper continues with an explanation of the less well documented indirect ecological effects of nutrient enrichment on stream structure and function, including effects of excess growth on physical habitat, and alterations to aquatic life community structure from the microbial assemblage to fish and mammals. The paper also dicusses effects on the ecosystem level including changes to productivity, respiration, decomposition, carbon and other geochemical cycles. The paper ends by discussing the significance of these direct and indirect effects of nutrient enrichment on designated uses - especially recreational, aquatic life, and drinking water. 2 1. Introduction 1.1 Stream processes Streams are all flowing natural waters, regardless of size. To understand the processes that influence the pattern and character of streams and reduce natural variation of different streams, several stream classification systems (including ecoregional, fluvial geomorphological, and stream order classification) have been adopted by state and national programs. Ecoregional classification is based on geology, soils, geomorphology, dominant land uses, and natural vegetation (Omernik 1987). Fluvial geomorphological classification explains stream and slope processes through the application of physical principles. Rosgen (1994) classified stream channels in the United States into seven major stream types based on morphological characteristics, including entrenchment, gradient, width/depth ratio, and sinuosity in various land forms. -

Capture, Identification and Culture Techniques of Coral Reef Fish Larvae

COMPONENT 2A - Project 2A1 PCC development February 2009 TRAINING COURSE REPORT CCapture,apture, iidentidentifi ccationation aandnd ccultureulture ttechniquesechniques ooff ccoraloral rreefeef fi sshh llarvaearvae ((FrenchFrench PPolynesia)olynesia) AAuthor:uthor: VViliameiliame PitaPita WaqalevuWaqalevu Photo credit: Eric CLUA The CRISP Coordinating Unit (CCU) was integrated into the Secretariat of the Pacifi c Community in April 2008 to insure maximum coordination and synergy in work relating to coral reef management in the region. The CRISP programme is implemented as part of the policy developed by the Secretariat of the Pacifi c Regional Environment Programme for a contribution to conservation and sustainable development of coral reefs in the Pacifi c he Initiative for the Protection and Management The CRISP Programme comprises three major compo- T of Coral Reefs in the Pacifi c (CRISP), sponsored nents, which are: by France and prepared by the French Development Agency (AFD) as part of an inter-ministerial project Component 1A: Integrated Coastal Management and from 2002 onwards, aims to develop a vision for the Watershed Management future of these unique ecosystems and the communi- - 1A1: Marine biodiversity conservation planning ties that depend on them and to introduce strategies - 1A2: Marine Protected Areas and projects to conserve their biodiversity, while de- - 1A3: Institutional strengthening and networking veloping the economic and environmental services - 1A4: Integrated coastal reef zone and watershed that they provide both locally and globally. Also, it is management designed as a factor for integration between deve- Component 2: Development of Coral Ecosystems loped countries (Australia, New Zealand, Japan and - 2A: Knowledge, benefi cial use and management USA), French overseas territories and Pacifi c Island de- of coral ecosytems veloping countries. -

Microscale Ecology Regulates Particulate Organic Matter Turnover in Model Marine Microbial Communities

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05159-8 OPEN Microscale ecology regulates particulate organic matter turnover in model marine microbial communities Tim N. Enke1,2, Gabriel E. Leventhal 1, Matthew Metzger1, José T. Saavedra1 & Otto X. Cordero1 The degradation of particulate organic matter in the ocean is a central process in the global carbon cycle, the mode and tempo of which is determined by the bacterial communities that 1234567890():,; assemble on particle surfaces. Here, we find that the capacity of communities to degrade particles is highly dependent on community composition using a collection of marine bacteria cultured from different stages of succession on chitin microparticles. Different particle degrading taxa display characteristic particle half-lives that differ by ~170 h, comparable to the residence time of particles in the ocean’s mixed layer. Particle half-lives are in general longer in multispecies communities, where the growth of obligate cross-feeders hinders the ability of degraders to colonize and consume particles in a dose dependent manner. Our results suggest that the microscale community ecology of bacteria on particle surfaces can impact the rates of carbon turnover in the ocean. 1 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA. 2 Department of Environmental Systems Science, ETH Zurich, Zürich 8092, Switzerland. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to O.X.C. (email: [email protected]) NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | (2018) 9:2743 | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05159-8 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 ARTICLE NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05159-8 earning how the composition of ecological communities the North Pacific gyre20. -

Fishes of Terengganu East Coast of Malay Peninsula, Malaysia Ii Iii

i Fishes of Terengganu East coast of Malay Peninsula, Malaysia ii iii Edited by Mizuki Matsunuma, Hiroyuki Motomura, Keiichi Matsuura, Noor Azhar M. Shazili and Mohd Azmi Ambak Photographed by Masatoshi Meguro and Mizuki Matsunuma iv Copy Right © 2011 by the National Museum of Nature and Science, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu and Kagoshima University Museum All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Copyrights of the specimen photographs are held by the Kagoshima Uni- versity Museum. For bibliographic purposes this book should be cited as follows: Matsunuma, M., H. Motomura, K. Matsuura, N. A. M. Shazili and M. A. Ambak (eds.). 2011 (Nov.). Fishes of Terengganu – east coast of Malay Peninsula, Malaysia. National Museum of Nature and Science, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu and Kagoshima University Museum, ix + 251 pages. ISBN 978-4-87803-036-9 Corresponding editor: Hiroyuki Motomura (e-mail: [email protected]) v Preface Tropical seas in Southeast Asian countries are well known for their rich fish diversity found in various environments such as beautiful coral reefs, mud flats, sandy beaches, mangroves, and estuaries around river mouths. The South China Sea is a major water body containing a large and diverse fish fauna. However, many areas of the South China Sea, particularly in Malaysia and Vietnam, have been poorly studied in terms of fish taxonomy and diversity. Local fish scientists and students have frequently faced difficulty when try- ing to identify fishes in their home countries. During the International Training Program of the Japan Society for Promotion of Science (ITP of JSPS), two graduate students of Kagoshima University, Mr. -

Plankton Community Composition, Organic Carbon and Thorium-234 Particle Size Distributions, and Particle Export in the Sargasso Sea

Journal of Marine Research, 67, 845–868, 2009 Plankton community composition, organic carbon and thorium-234 particle size distributions, and particle export in the Sargasso Sea by H. S. Brew1, S. B. Moran1,2, M. W. Lomas3 and A. B. Burd4 ABSTRACT Measurements of plankton community composition (eight planktonic groups), particle size- fractionated (10, 20, 53, 70, and 100-m Nitex screens) distributions of organic carbon (OC) and 234Th, and particle export of OC and 234Th are reported over a seasonal cycle (2006–2007) from the Bermuda Atlantic Time-Series (BATS) site. Results indicate a convergence of the particle size distributions of OC and 234Th during the winter-spring bloom period (January–March, 2007). The observed convergence of these particle size distributions is directly correlated to the depth-integrated abundance of autotrophic pico-eukaryotes (r ϭ 0.97, P Ͻ 0.05) and, to a lesser extent, Synechococcus (r ϭ 0.85, P ϭ 0.14). In addition, there are positive correlations between the sediment trap flux of OC and 234Th at 150 m and the depth-integrated abundance of pico-eukaryotes (r ϭ 0.94, P ϭ 0.06 for OC, and r ϭ 0.98, P Ͻ 0.05 for 234Th) and Synechococcus (r ϭ 0.95, P ϭ 0.05 for OC, and r ϭ 0.94, P ϭ 0.06 for 234Th). An implication of these observations and recent modeling studies (Richardson and Jackson, 2007) is that, although small in size, pico-plankton may influence large particle export from the surface waters of the subtropical Atlantic. -

First Records of the Fish Abudefduf Sexfasciatus (Lacepède, 1801) and Acanthurus Sohal (Forsskål, 1775) in the Mediterranean Sea

BioInvasions Records (2018) Volume 7, Issue 2: 205–210 Open Access DOI: https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2018.7.2.14 © 2018 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2018 REABIC Rapid Communication First records of the fish Abudefduf sexfasciatus (Lacepède, 1801) and Acanthurus sohal (Forsskål, 1775) in the Mediterranean Sea Ioannis Giovos1,*, Giacomo Bernardi2, Georgios Romanidis-Kyriakidis1, Dimitra Marmara1 and Periklis Kleitou1,3 1iSea, Environmental Organization for the Preservation of the Aquatic Ecosystems, Thessaloniki, Greece 2Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, USA 3Marine and Environmental Research (MER) Lab Ltd., Limassol, Cyprus *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] Received: 26 October 2017 / Accepted: 16 January 2018 / Published online: 14 March 2018 Handling editor: Ernesto Azzurro Abstract To date, the Mediterranean Sea has been subjected to numerous non-indigenous species’ introductions raising the attention of scientists, managers, and media. Several introduction pathways contribute to these introduction, including Lessepsian migration via the Suez Canal, accounting for approximately 100 fish species, and intentional or non-intentional aquarium releases, accounting for at least 18 species introductions. In the context of the citizen science project of iSea “Is it alien to you?… Share it”, several citizens are engaged and regularly report observations of alien, rare or unknown marine species. The project aims to monitor the establishment and expansion of alien species in Greece. In this study, we present the first records of two popular high-valued aquarium species, the scissortail sergeant, Abudefduf sexfasciatus and the sohal surgeonfish, Acanthurus sohal, in along the Mediterranean coastline of Greece. The aggressive behaviour of the two species when in captivity, and the absence of records from areas close to the Suez Canal suggest that both observations are the result of aquarium intentional releases, rather than a Lessepsian migration. -

A View of Physical Mechanisms for Transporting Harmful Algal Blooms to T Massachusetts Bay ⁎ Yu Zhanga, , Changsheng Chenb, Pengfei Xueb,1, Robert C

Marine Pollution Bulletin 154 (2020) 111048 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Pollution Bulletin journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/marpolbul A view of physical mechanisms for transporting harmful algal blooms to T Massachusetts Bay ⁎ Yu Zhanga, , Changsheng Chenb, Pengfei Xueb,1, Robert C. Beardsleyc, Peter J.S. Franksd a College of Marine Sciences, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai 201306, PR China b School for Marine Science and Technology, University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth, New Bedford, MA 02744, USA c Department of Physical Oceanography, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA d Integrative Oceanography Division, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Physical dynamics of Harmful Algal Blooms in Massachusetts Bay in May 2005 and 2008 were examined by the Harmful algal bloom simulated results. Reverse particle-tracking experiments suggest that the toxic phytoplankton mainly originated Massachusetts Bay from the Bay of Fundy in 2005 and the western Maine coastal region and its local rivers in 2008. Mechanism Ocean modeling studies suggest that the phytoplankton were advected by the Gulf of Maine Coastal Current (GMCC). In 2005, Lagrangian flow Nor'easters increased the cross-shelf surface elevation gradient over the northwestern shelf. This intensified the Eastern and Western MCC to form a strong along-shelf current from the Bay of Fundy to Massachusetts Bay. In 2008, both Eastern and Western MCC were established with a partial separation around Penobscot Bay before the outbreak of the bloom. The northeastward winds were too weak to cancel or reverse the cross-shelf sea surface gradient, so that the Western MCC carried the algae along the slope into Massachusetts Bay. -

Energetic Costs of Chronic Fish Predation on Reef-Building Corals

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Cole, Andrew (2011) Energetic costs of chronic fish predation on reef-building corals. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/37611/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/37611/ The energetic costs of chronic fish predation on reef-building corals Thesis submitted by Andrew Cole BSc (Hons) September 2011 For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Marine Biology ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies and the School of Marine and Tropical Biology James Cook University Townsville, Queensland, Australia Statement of Access I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that James Cook University will make it available for use within the University Library and via the Australian Digital Thesis Network for use elsewhere. I understand that as an unpublished work this thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and I do not wish to put any further restrictions upon access to this thesis. 09/09/2011 (signature) (Date) ii Statement of Sources Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at my university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. -

Ecomorfologia E Padrões De Abundância De Labridae Em Ilhas Oceânicas E Áreas Da Costa Brasileira

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO ESPÍRITO SANTO CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS E NATURAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS BIOLÓGICAS Ecomorfologia e padrões de abundância de Labridae em ilhas oceânicas e áreas da costa brasileira Gabriel Costa Cardozo Ferreira Vitória, ES Fevereiro, 2015 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO ESPÍRITO SANTO CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS E NATURAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS BIOLÓGICAS Ecomorfologia e padrões de abundância de Labridae em ilhas oceânicas e áreas da costa brasileira Gabriel Costa Cardozo Ferreira Orientador: Jean-Christophe Joyeux Co-orientador: Ronaldo Bastos Francini-Filho Dissertação submetida ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas (Biologia Animal) da Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo como requisito parcial para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Biologia Animal Vitória, ES Fevereiro, 2015 SUMÁRIO Introdução Geral .................................................................................................................. 11 Referências ...................................................................................................................... 14 Capítulo 1 ............................................................................................................................ 18 Variações ontogenéticas em grupos funcionais de Labridae do Atlântico sudoeste ............. 18 Resumo ............................................................................................................................ 18 Abstract ........................................................................................................................... -

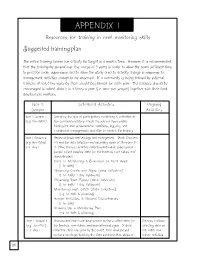

APPENDIX 1 Resources for Training in Reef Monitoring Skills Suggested Training Plan the Entire Training Course Can Actually Be Taught in a WeekS Time

APPENDIX 1 Resources for training in reef monitoring skills Suggested training plan The entire training course can actually be taught in a weeks time. However, it is recommended that the training be spread over the course of 3 years in order to allow the team sufficient time to practice under supervision and to allow the study area to actually change in response to management activities enough to be observed. If a community is being trained by external trainers, at least two visits by them should be planned for each year. The trainees should be encouraged to collect data 2 to 4 times a year (i.e. once per season) together with their local development workers. Year & Scheduled Activities Ongoing Season Activities Year 1. Season 1. Introduce the idea of participatory monitoring & evaluation to (e.g. Nov.-Mar.) key community leaders. Check the site for appropriate biophysical and socioeconomic conditions, logistics, and counterpart arrangements and offer to conduct the training. Year 1. Season 2. Review of basic reef ecology and management. Teach Chapters (e.g. Apr.-May) 1-4 and the data collection and recording steps of Chapters 5- 3-4 days 9. Have trainees practice collecting data while experienced people collect baseline data (on the benthos, reef fishes, and invertebrates). Intro to Monitoring & Evaluation of Coral Reefs (1 hr talk) Observing Corals and Algae [data collection] (1 hr talk/ 1 day fieldwork) Observing Reef Fishes [data collection] (1 hr talk/ 1 day fieldwork) Monitoring Fish Catch [data collection] (1-2 hr talk & planning) Human Activities & Natural Disturbances (1 hr talk) Drawing Up a Monitoring Plan (1-2 hr talk & planning) Year 1.