Harmful Algal Blooms (Habs) and Desalination: a Guide to Impacts, Monitoring, and Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for Design and Sampling for Cyanobacterial Toxin and Taste-And-Odor Studies in Lakes and Reservoirs

Guidelines for Design and Sampling for Cyanobacterial Toxin and Taste-and-Odor Studies in Lakes and Reservoirs Scientific Investigations Report 2008–5038 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Photo 1 Photo 3 Photo 2 Front cover. Photograph 1: Beach sign warning of the presence of a cyanobacterial bloom, June 29, 2006 (photograph taken by Jennifer L. Graham, U.S. Geological Survey). Photograph 2: Sampling a near-shore accumulation of Microcystis, August 8, 2006 (photograph taken by Jennifer L. Graham, U.S. Geological Survey). Photograph 3: Mixed bloom of Anabaena, Aphanizomenon, and Microcystis, August 10, 2006 (photograph taken by Jennifer L. Graham, U.S. Geological Survey). Background photograph: Near-shore accumulation of Microcystis, August 8, 2006 (photograph taken by Jennifer L. Graham, U.S. Geological Survey). Guidelines for Design and Sampling for Cyanobacterial Toxin and Taste-and-Odor Studies in Lakes and Reservoirs By Jennifer L. Graham, Keith A. Loftin, Andrew C. Ziegler, and Michael T. Meyer Scientific Investigations Report 2008–5038 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2008 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Cyanobacterial Toxins: Saxitoxins

WHO/SDE/WSH/xxxxx English only Cyanobacterial toxins: Saxitoxins Background document for development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality and Guidelines for Safe Recreational Water Environments Version for Public Review Nov 2019 © World Health Organization 20XX Preface Information on cyanobacterial toxins, including saxitoxins, is comprehensively reviewed in a recent volume to be published by the World Health Organization, “Toxic Cyanobacteria in Water” (TCiW; Chorus & Welker, in press). This covers chemical properties of the toxins and information on the cyanobacteria producing them as well as guidance on assessing the risks of their occurrence, monitoring and management. In contrast, this background document focuses on reviewing the toxicological information available for guideline value derivation and the considerations for deriving the guideline values for saxitoxin in water. Sections 1-3 and 8 are largely summaries of respective chapters in TCiW and references to original studies can be found therein. To be written by WHO Secretariat Acknowledgements To be written by WHO Secretariat 5 Abbreviations used in text ARfD Acute Reference Dose bw body weight C Volume of drinking water assumed to be consumed daily by an adult GTX Gonyautoxin i.p. intraperitoneal i.v. intravenous LOAEL Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level neoSTX Neosaxitoxin NOAEL No Observed Adverse Effect Level P Proportion of exposure assumed to be due to drinking water PSP Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning PST paralytic shellfish toxin STX saxitoxin STXOL saxitoxinol -

Save the Reef

Save the Reef A member group of Lock the Gate Alliance www.savethereef.net.au Committee Secretary Senate Standing Committees on Environment and Communications PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Phone: +61 2 6277 3526 Fax: +61 2 6277 5818 [email protected] Submission to the Senate Inquiry on The adequacy of the Australian and Queensland Governments’ efforts to stop the rapid decline of the Great Barrier Reef, including but not limited to: Points a–k. Save the Reef would like to thank this committee for the opportunity to make a submission and would also like to speak further if there is an opportunity at any public hearings. The Great Barrier Reef is Australia’s greatest natural asset. It is a tourism mecca, a 6 billion dollar economic boon as well as a scientific wonderland. It is a World Heritage Listed property and an acknowledged world wonder. The Great Barrier Reef is part of Australia’s very identity. We are failing to protect the Great Barrier Reef. The efforts to stop the rapid decline of the Great Barrier Reef are grossly inadequate. It demonstrates that our current system for protecting the environment is broken. Environmental impact statements, conditions, offsets, regulations, enforcement and even the EPBC act, processes meant to protect the environment are being subverted and the impact is apparent. The holes in the “Swiss Cheese” are lining up and have allowed and are continuing to allow further destruction of the Great Barrier Reef when it needs our protection the most. The recent developments in Gladstone are a clear demonstration of the failure of our systems. -

Sample Chapter Algal Blooms

ALGAL BLOOMS 7 Observations and Remote Sensing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ energy and material transport through the food web, and JSTARS.2013.2265255. they also play an important role in the vertical flux of Pack, R. T., Brooks, V., Young, J., Vilaca, N., Vatslid, S., Rindle, P., material out of the surface waters. These blooms are Kurz, S., Parrish, C. E., Craig, R., and Smith, P. W., 2012. An “ ” overview of ALS technology. In Renslow, M. S. (ed.), Manual distinguished from those that are deemed harmful. of Airborne Topographic Lidar. Bethesda: ASPRS Press. Algae form harmful algal blooms, or HABs, when either Sithole, G., and Vosselman, G., 2004. Experimental comparison of they accumulate in massive amounts that alone cause filter algorithms for bare-Earth extraction from airborne laser harm to the ecosystem or the composition of the algal scanning point clouds. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and community shifts to species that make compounds Remote Sensing, 59,85–101. (including toxins) that disrupt the normal food web or to Shan, J., and Toth, C., 2009. Topographic Laser Ranging and Scanning: Principles and Processes. Boca Raton: CRC Press. species that can harm human consumers (Glibert and Slatton, K. C., Carter, W. E., Shrestha, R. L., and Dietrich, W., 2007. Pitcher, 2001). HABs are a broad and pervasive problem, Airborne laser swath mapping: achieving the resolution and affecting estuaries, coasts, and freshwaters throughout the accuracy required for geosurficial research. Geophysical world, with effects on ecosystems and human health, and Research Letters, 34,1–5. on economies, when these events occur. This entry Wehr, A., and Lohr, U., 1999. -

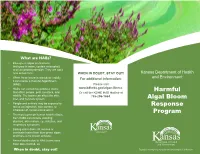

Harmful Algal Bloom Response Program

What are HABs? • Blue-green algae are bacteria that grow in water, contain chlorophyll, and can photosynthesize. They are not a new occurrence. WHEN IN DOUBT, STAY OUT! Kansas Department of Health • When these bacteria reproduce rapidly, For additional information: and Environment it can create a Harmful Algal Bloom (HAB). Please visit • HABs can sometimes produce toxins www.kdheks.gov/algae-illness. Harmful that affect people, pets, livestock, and Or call the KDHE HAB Hotline at wildlife. The toxins can affect the skin, 785-296-1664. liver, and nervous system. Algal Bloom • People and animals may be exposed to toxins via ingestion, skin contact, or Response inhalation of contaminated water. Program • The most common human health effects from HABs can include vomiting, diarrhea, skin rashes, eye irritation, and respiratory symptoms. • Boiling water does not remove or Department of Health inactivate toxins from blue-green algae, and Environment and there is no known antidote. • Animal deaths due to HAB toxins have Department of Health been documented, so: and Environment When in doubt, stay out! To protect and improve the health and environment of all Kansans. How else is KDHE working to What causes HABs? HAB Advisory Levels prevent HABs? Blue-green algae are a natural part of water- Threshold Levels based ecosystems. They become a problem Harmful Algal Blooms thrive in the presence when nutrients (phosphorus and nitrogen) are Watch Warning Closure of excess nutrients such as nitrogen and present in concentrations above what would phosphorus. Thus, KDHE continually works to occur naturally. Under these conditions, algae blue green reduce nutrient input and improve overall can grow very quickly to extreme numbers, cell counts 80,000 250,000 10,000,000 water quality through a series of interrelated resulting in a Harmful Algal Bloom. -

The Spatial and Temporal Distribution and Environmental Drivers Of

THE SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL DISTRIBUTION AND POTENTIAL ENVIRONMENTAL DRIVERS OF SAXITOXIN IN NORTHWEST OHIO Callie A. Nauman A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May 2020 Committee: Timothy Davis, Advisor George Bullerjahn Justin Chaffin © 2020 Callie A. Nauman All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Timothy Davis, Advisor Cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms threaten freshwater quality and human health around the world. One specific threat is the ability of some cyanobacteria to produce multiple types of toxins, including a range of neurotoxins called saxitoxins. While it is not completely understood, the general consensus is environmental factors like phosphorus, nitrogen, and light availability, may be driving forces in saxitoxin production. Recent surveys have determined saxitoxin and potential saxitoxin producing cyanobacterial species in both lakes and rivers across the United States and Ohio. Research evaluating benthic cyanobacterial blooms determined benthic cyanobacteria as a source for saxitoxin production in systems, specifically rivers. Currently, little is known about when, where, why, or who is producing saxitoxin in Ohio, and even less is known about the role benthic cyanobacterial blooms play in Ohio waterways. With increased detections of saxitoxin, the saxitoxin biosynthesis gene sxtA, and saxitoxin producing species in both the Western Basin of Lake Erie and the lake’s major tributary the Maumee River, seasonal sampling was conducted to monitor saxitoxin in both systems. The sampling took place from late spring to early autumn of 2018 and 2019. Monitoring including bi-/weekly water column sampling in the Maumee River and Lake Erie and Nutrient Diffusing Substrate (NDS) Experiments, were completed to evaluate saxitoxin, sxtA, potential environmental drivers, and benthic production. -

Harmful Algal Bloom Online Resources

Harmful Algal Bloom Online Resources General Information • CDC Harmful Algal Bloom-Associated Illnesses Website • CDC Harmful Algal Blooms Feature • EPA CyanoHABs Website • EPA Harmful Algal Blooms & Cyanobacteria Research Website • NOAA Harmful Algal Bloom Website • NOAA Harmful Algal Bloom and Hypoxia Research Control Act Harmful Algal Bloom Monitoring and Tracking • EPA Cyanobacteria Assessment Network (CyAN) Project • NCCOS Harmful Algal Bloom Research Website • NOAA Harmful Algal Bloom Forecasts • USGS Summary of Cyanobacteria Monitoring and Assessments in USGS Water Science Centers • WHO Toxic Cyanobacteria in water: A guide to their public health consequences, monitoring, and management Harmful Algal Blooms and Drinking Water • AWWA Assessment of Blue-Green Algal Toxins in Raw and Finished Drinking Water • EPA Guidelines and Recommendations • EPA Harmful Algal Bloom & Drinking Water Treatment Website • EPA Algal Toxin Risk Assessment and Management Strategic Plan for Drinking Water Document • USGS Drinking Water Exposure to Chemical and Pathogenic Contaminants: Algal Toxins and Water Quality Website Open Water Resources • CDC Healthy Swimming Website - Oceans, Lakes, Rivers • EPA State Resources Website • EPA Beach Act Website • EPA Beach Advisory and Closing On-line Notification (BEACON) • USG Guidelines for Design and Sampling for Cyanobacterial Toxin and Taste-and-Odor Studies in Lakes and Reservoirs • NALMS Inland HAB Program • NOAA Illinois-Indiana and Michigan Sea Grant Beach Manager’s Manual • USGS Field and Laboratory Guide -

Can't Catch My Breath! a Study of Metabolism in Fish. Subjects

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 2017 Can’t Catch My Breath! A Study of Metabolism in Fish. Subjects: Environmental Science, Marine/Ocean Science, Life Science/ Biology Grades: 6-8 Gail Schweiterman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Marine Biology Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Schweiterman, G. (2017) Can’t Catch My Breath! A Study of Metabolism in Fish. Subjects: Environmental Science, Marine/Ocean Science, Life Science/Biology Grades: 6-8. VA SEA 2017 Lesson Plans. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V5414G This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Can’t catch my breath! A study of metabolism in fish Gail Schwieterman Virginia Institute of Marine Science Grade Level High School Subject area Biology, Environmental, or Marine Science This work is sponsored by the National Estuarine Research Reserve System Science Collaborative, which supports collaborative research that addresses coastal management problems important to the reserves. The Science Collaborative is funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and managed by the University of Michigan Water Center. 1. Activity Title: Can’t Catch My Breath! A study of metabolism in fish 2. Focus: Metabolism (Ecological drivers); The Scientific Method (Formulating Hypothesis) 3. Grade Levels/ Subject: HS Biology, HS Marine Biology 4. VA Science Standard(s) addressed: BIO.1. The student will demonstrate an understanding of scientific reasoning, logic, and the nature of science by planning and conducting investigations (including most Essential Understandings and nearly all Essential Knowledge and Skills) BIO.4a. -

Habs in UPWELLING SYSTEMS

GEOHAB CORE RESEARCH PROJECT: HABs IN UPWELLING SYSTEMS 1 GEOHAB GLOBAL ECOLOGY AND OCEANOGRAPHY OF HARMFUL ALGAL BLOOMS GEOHAB CORE RESEARCH PROJECT: HABS IN UPWELLING SYSTEMS AN INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMME SPONSORED BY THE SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE ON OCEANIC RESEARCH (SCOR) AND THE INTERGOVERNMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHIC COMMISSION (IOC) OF UNESCO EDITED BY: G. PITCHER, T. MOITA, V. TRAINER, R. KUDELA, P. FIGUEIRAS, T. PROBYN BASED ON CONTRIBUTIONS BY PARTICIPANTS OF THE GEOHAB OPEN SCIENCE MEETING ON HABS IN UPWELLING SYSTEMS AND THE GEOHAB SCIENTIFIC STEERING COMMITTEE February 2005 3 This report may be cited as: GEOHAB 2005. Global Ecology and Oceanography of Harmful Algal Blooms, GEOHAB Core Research Project: HABs in Upwelling Systems. G. Pitcher, T. Moita, V. Trainer, R. Kudela, P. Figueiras, T. Probyn (Eds.) IOC and SCOR, Paris and Baltimore. 82 pp. This document is GEOHAB Report #3. Copies may be obtained from: Edward R. Urban, Jr. Henrik Enevoldsen Executive Director, SCOR Programme Co-ordinator Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences IOC Science and Communication Centre on The Johns Hopkins University Harmful Algae Baltimore, MD 21218 U.S.A. Botanical Institute, University of Copenhagen Tel: +1-410-516-4070 Øster Farimagsgade 2D Fax: +1-410-516-4019 DK-1353 Copenhagen K, Denmark E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +45 33 13 44 46 Fax: +45 33 13 44 47 E-mail: [email protected] This report is also available on the web at: http://www.jhu.edu/scor/ http://ioc.unesco.org/hab ISSN 1538-182X Cover photos courtesy of: Vera Trainer Teresa Moita Grant Pitcher Copyright © 2005 IOC and SCOR. -

![Cyanobacteria and Cyanotoxin Analysis and Testing Services [As of 3/15/2016]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1563/cyanobacteria-and-cyanotoxin-analysis-and-testing-services-as-of-3-15-2016-1071563.webp)

Cyanobacteria and Cyanotoxin Analysis and Testing Services [As of 3/15/2016]

Cyanobacteria/Cyanotoxin Testing Services List Developed by the NEIWPCC HAB Workgroup (Northeast state health and environmental agency staff). The New England Interstate Water Pollution Control Commission is a non-profit organization established through an act of Congress in 1947. NEIWPCC strives to: coordinate activities and forums that encourage cooperation among the states; educate the public about key environmental issues; support research projects, train environmental professionals, and provide overall leadership in the management and protection of water quality. Cyanobacteria and Cyanotoxin Analysis and Testing Services [As of 3/15/2016] Disclaimer: Individuals and/or companies listed below have been identified as performing services related to cyanobacteria and cyanotoxin analysis. This should not be considered an endorsement by NEIWPCC or any state agency of their qualifications. Public Water Systems considering contracting with any individual or company should verify that they have the adequate training and are competent to perform the work for which they are being considered. Prices should be viewed as guidelines of what to expect for each lab, rather than final quotes – many offer discounts, e.g., for bulk samples. Academy of Natural Sciences – Phycology Section Patrick Center for Environmental Research 1900 Benjamin Franklin Parkway Philadelphia, PA 19103 Tel: (215) 299-1080 Fax: (215) 299-1079 Email General: [email protected] Email Don Charles: [email protected] Email Frank Acker (primary soft-algae taxonomist): [email protected] Services: Identification of algae and algal measurements/biovolume, cell counts, chlorophyll Pricing: (Can give estimate based on sample, and separate the phytoplankton and periphyton in terms of how they are processed) Semiquantitative count (relative abundance, five-point scale, rare to abundant) – $150-200 Algal identification (cell count, biovolume) – $440-550 Chlorophyll (fluorometer) – Call for cost Diatom count – $300 Aquatic Services, Wayne Carmichael, Ph.D. -

Marine Plants in Coral Reef Ecosystems of Southeast Asia by E

Global Journal of Science Frontier Research: C Biological Science Volume 18 Issue 1 Version 1.0 Year 2018 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Online ISSN: 2249-4626 & Print ISSN: 0975-5896 Marine Plants in Coral Reef Ecosystems of Southeast Asia By E. A. Titlyanov, T. V. Titlyanova & M. Tokeshi Zhirmunsky Institute of Marine Biology Corel Reef Ecosystems- The coral reef ecosystem is a collection of diverse species that interact with each other and with the physical environment. The latitudinal distribution of coral reef ecosystems in the oceans (geographical distribution) is determined by the seawater temperature, which influences the reproduction and growth of hermatypic corals − the main component of the ecosystem. As so, coral reefs only occupy the tropical and subtropical zones. The vertical distribution (into depth) is limited by light. Sun light is the main energy source for this ecosystem, which is produced through photosynthesis of symbiotic microalgae − zooxanthellae living in corals, macroalgae, seagrasses and phytoplankton. GJSFR-C Classification: FOR Code: 060701 MarinePlantsinCoralReefEcosystemsofSoutheastAsia Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of : © 2018. E. A. Titlyanov, T. V. Titlyanova & M. Tokeshi. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Marine Plants in Coral Reef Ecosystems of Southeast Asia E. A. Titlyanov α, T. V. Titlyanova σ & M. Tokeshi ρ I. Coral Reef Ecosystems factors for the organisms’ abundance and diversity on a reef. -

Harmful Algal Blooms

NSF GK-12 Graduate Fellows Program Award # DGE-0139171 University of North Carolina at Wilmington Harmful Algal Blooms by Tika Knierim, Department of Chemistry This activity is aligned with the 2001 North Carolina Standard Course of Study for 8th Grade Science: Goal # 1 & 2 Algal species sometimes make their presence known as a massive “bloom” of cells that may discolor the water These “blooms” alter marine habitats Every coastal state has reported major blooms Although they are referred to as harmful algal blooms, not all HABs are toxic Toxic blooms are caused by algae that produce potent toxins that can cause massive fish kills, marine mammal deaths, and human illness There are several types of toxins produced by these harmful algae. .commonly the toxins affect the functioning of nerve and muscle cells Toxic blooms have been responsible for causing diarrhea, vomiting, numbness, dizziness, paralysis, and even death The key is how the toxins move through the food web The key to this scenario is bioaccumulation!! BIOACCUMULATION is the process by which compounds accumulate or build up in an organism at a faster rate than they can be broken down. Some organisms, such as krill, mussels, anchovies, and mackerel, have been found to retain toxins in their bodies Today we are going to do a little activity in order to better understand the concept of bioaccumulation and how toxins are transferred through the food chain. Each person will be assigned one of the following organisms: Krill: Seal: Fish: Killer Whale: There is an outbreak of a Harmful Algal Bloom within the boundaries of this classroom, and there is algae (green beads) spread all over the area.