Thesis Document (13.19Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fort Niagara Flag Is Crown Jewel of Area's Rich History

Winter 2009 Fort Niagara TIMELINE The War of 1812 Ft. Niagara Flag The War of 1812 Photo courtesy of Angel Art, Ltd. Lewiston Flag is Crown Ft. Niagara Flag History Jewel of Area’s June 1809: Ft. Niagara receives a new flag Mysteries that conforms with the 1795 Congressional act that provides for 15 starts and 15 stripes Rich History -- one for each state. It is not known There is a huge U.S. flag on display where or when it was constructed. (There were actually 17 states in 1809.) at the new Fort Niagara Visitor’s Center that is one of the most valued historical artifacts in the December 19, 1813: British troops cap- nation. The War of 1812 Ft. Niagara flag is one of only 20 ture the flag during a battle of the War of known surviving examples of the “Stars and Stripes” that were 1812 and take it to Quebec. produced prior to 1815. It is the earliest extant flag to have flown in Western New York, and the second oldest to have May 18, 1814: The flag is sent to London to be “laid at the feet of His Royal High- flown in New York State. ness the Prince Regent.” Later, the flag Delivered to Fort Niagara in 1809, the flag is older than the was given as a souvenir to Sir Gordon Star Spangled Banner which flew over Ft. McHenry in Balti- Drummond, commander of the British more. forces in Ontario. Drummond put it in his As seen in its display case, it dwarfs home, Megginch Castle in Scotland. -

10-2 157410 Volumes 1-7 Open FA 10-2

10-2_157410_volumes_1-7_open FA 10-2 RG Volume Reel no. Title / Titre Dates no. / No. / No. de de bobine volume RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-05-27 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-08-31 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-11-17 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-12-28 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 William Dummer Powell to Peter Russell respecting Joseph Brant 1797-01-05 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Robert Prescott to Peter Russell respecting the Indian Department - Enclosed: Copy of Duke of 1797-04-26 Portland to Prescott, 13 December 1796, stating that the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada will head the Indian Department, but that the Department will continue to be paid from the military chest - Enclosed: Copy of additional instructions to Lieutenant Governor U.C., 15 December 1796, respecting the Indian Department - Enclosed: Extract, Duke of Portland to Prescott, 13 December 1796, respecting Indian Department in U.C. RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Robert Prescott to Peter Russell sending a copy of Robert Liston's letter - Enclosed: Copy, 1797-05-18 Robert Liston to Prescott, 22 April 1797, respecting the frontier posts RG10-A-1-a -

3676 Tee London Gazette, July 26' 1881

3676 TEE LONDON GAZETTE, JULY 26' 1881. Lieutenant-general the Honourable James William 'Lieutenant-Colonel Oliver Henry Atkins Nicollsv BosvilleMacdonald, C.B., Colonel 21st Hussars. Royal Artillery. Lieutenant-General William Richard Preston. Lieutenant-Colonel Augustus Edmund Warren*,. Lieutenant-General' Thomas Conyngham Kelly, Seaforth Highlanders (Ross-shire Buffs). C.B. ' Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Bennett, the Duke of Lieutenant-General Richard Walter Lacy. Cornwall's Light Infantry. Lieutenant-General Ralph Budd. j Lieutenant-Colonel James Briggs, the Manchester Lieutenant-General John Amber Cole. Regiment. To be Lieutenant-General. Lieutenant-Colonel Edmund Penrose Bingham Major-General James Henry Craig Robertson. Turner, Royal Artillery. 1 Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Andrew Stuart, the= The following- Major-Generals to be Lieu- Royal Scots (Lothian Regiment). tenant-Generals from 1st July, 188.1,. to complete Lieutenant-Colonel Ralph Gore, Royal Artillery. the Establishment allowed for the Royal Engi- Lieutenant-Colonel Somerville George Cameron neers :— Hogge, Princess Charlotte of Wales's (Berkshire Spencer Westmacott, Royal Engineers. Regiment). William Collier Menzies, Royal Engineers. Lieutenant-Colonel Hubert Le Cocq, Royal (Iate= Sir Robert Michael Laffan, K.C.M.G., Royal Bombay) Artillery. Engineers. Lieutenant-Colonel Philip Alexander Anstruther The undermentioned General Officers to be Twynam, the East Yorkshire Regimenr. Supernumerary to the Establishment, under the Lieutenant-Colonel John Sidney Hand, the Essex. provisions of Article. 24 I of the Royal War- Regiment. rant of 25th June, 1881 :->- Lieutenant-Colonel Harry McLeod, Royal (late General Robert Cornelia, Lord Napier of Mag- Madras) Artillery. dala, G.C.B., G.C.S.I., Colonel-Commandant. Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Edward Torriano, . Royal (late Bengal) Engineers. -

Chapter Xxiv

CHAPTER XXIV. Crown lands management Waste lands in seigniories Government officials Army bills redeemed Banking Political situation, 1816 The two Papineaus Sessions of 1817-1819 Death of George III., 1820 A speech of Louis-Joseph Papineau. To portion out the lands amongst the militia, General Drummond, the administrator of the province (1815), was constrained to have recourse to the officials of a department in which enormous abuses existed. The lands were divided up between favourites. So much territory had been given away that Drummond informed the minister that there was no more room on the River St. Francis for the establishment of the immigrants and the discharged soldiers. Every one had pounced down upon that immense pasture ground. From 1793 to 1811, over three million acres had been granted to a couple of hundred privileged applicants. Some of them secured as much as sixty to eighty thousand acres as, for example, Governor Milnes, who took nearly seventy thousand as his share. These people had no intention of ever improving the land by clearing it of the forest. As it cost them nothing, they purposed leaving the same in a wild state until such time as the development of the neigh- bourhood by colonization would increase the value of the whole. Another vexatious land question arose out of the vast domains granted by the King of France to the so-called seigneurs which were intended, by the letter and spirit of the grants themselves, to be given to the settlers whenever they wished for them. Large tracts of these still remained unoc- cupied and the seigneurs had often expressed the desire to get them as their own property in free and common socage, whilst the country people main- tained that they were to be kept en seigneurie according to the intention of the sovereign who first granted them. -

Un Imbroglio Territorial En Montérégie Au Temps Du Bas-Canada: La Seigneurie De La Salle

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL UN IMBROGLIO TERRITORIAL EN MONTÉRÉGIE AU TEMPS DU BAS-CANADA: LA SEIGNEURIE DE LA SALLE MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN HISTOIRE PAR HÉLÈNE TRUDEAU OCTOBRE 2007 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques Avertissement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supérieurs (SDU-522 - Rév.ü1-2ü06). Cette autorisation stipule que «conformément à l'article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs, [l'auteur] concède à l'Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d'utilisation et de publication de la totalité ou d'une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l'auteur] autorise l'Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire, diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de [son] travail de recherche à des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l'Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n'entraînent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l'auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire, [l'auteur] conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire.» AVANT-PROPOS Des voyageurs ont rapporté d'Angleterre un recueil contenant la reproduction de 169 pages manuscrites et portant les mentions «Transcripts of Colonial Office Records» et «From Public Record Office, London.». -

Constitution and Government 33

CONSTITUTION AND GOVERNMENT 33 GOVERNORS GENERAL OF CANADA. FRENCH. FKENCH. 1534. Jacques Cartier, Captain General. 1663. Chevalier de Saffray de Mesy. 1540. Jean Francois de la Roque, Sieur de 1665. Marquis de Tracy. (6) Roberval. 1665. Chevalier de Courcelles. 1598. Marquis de la Roche. 1672. Comte de Frontenac. 1600. Capitaine de Chauvin (Acting). 1682. Sieur de la Barre. 1603. Commandeur de Chastes. 1685. Marquis de Denonville. 1607. Pierredu Guast de Monts, Lt.-General. 1689. Comte de Frontenac. 1608. Comte de Soissons, 1st Viceroy. 1699. Chevalier de Callieres. 1612. Samuel de Champlain, Lt.-General. 1703. Marquis de Vaudreuil. 1633. ii ii 1st Gov. Gen'l. (a) 1714-16. Comte de Ramesay (Acting). 1635. Marc Antoine de Bras de fer de 1716. Marquis de Vaudreuil. Chateaufort (Administrator). 1725. Baron (1st) de Longueuil (Acting).. 1636. Chevalier de Montmagny. 1726. Marquis de Beauharnois. 1648. Chevalier d'Ailleboust de Coulonge. 1747. Comte de la Galissoniere. (c) 1651. Jean de Lauzon. 1749. Marquis de la Jonquiere. 1656. Charles de Lauzon-Charny (Admr.) 1752. Baron (2nd) de Longueuil. 1657. D'Ailleboust de Coulonge. 1752. Marquis Duquesne-de-Menneville. 1658. Vicomte de Voyer d'Argenson. j 1755. Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal. 1661. Baron Dubois d'Avaugour. ! ENGLISH. ENGLISH. 1760. General Jeffrey Amherst, (d) 1 1820. James Monk (Admin'r). 1764. General James Murray. | 1820. Sir Peregrine Maitland (Admin'r). 1766. P. E. Irving (Admin'r Acting). 1820. Earl of Dalhousie. 1766. Guy Carleton (Lt.-Gov. Acting). 1824. Lt.-Gov. Sir F. N. Burton (Admin'r). 1768. Guy Carleton. (e) 1828. Sir James Kempt (Admin'r). 1770. Lt.-Gov. -

Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-8-2020 "The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812 Joseph R. Miller University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Joseph R., ""The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3208. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3208 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE MEN WERE SICK OF THE PLACE”: SOLDIER ILLNESS AND ENVIRONMENT IN THE WAR OF 1812 By Joseph R. Miller B.A. North Georgia University, 2003 M.A. University of Maine, 2012 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine May 2020 Advisory Committee: Scott W. See, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-advisor Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Co-advisor Liam Riordan, Professor of History Kathryn Shively, Associate Professor of History, Virginia Commonwealth University James Campbell, Professor of Joint, Air War College, Brigadier General (ret) Michael Robbins, Associate Research Professor of Psychology Copyright 2020 Joseph R. -

The Limits of Social Mobility: Social Origins and Career Patterns of British Generals, 1688-1815

The London School of Economics and Political Science The Limits of Social Mobility: social origins and career patterns of British generals, 1688-1815 Andrew B. Wood A thesis submitted to the Department of Economic History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, November, 2011 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 88,820 words. 2 Abstract Late eighteenth-century Britain was dominated by two features of economic life that were a major departure from previous eras, the economic growth of the Industrial Revolution and almost constant warfare conducted on a previously unprecedented scale. One consequence of this was the rapid expansion, diversification and development of the professions. Sociologists and economists have often argued that economic development and modernisation leads to increasing rates of social mobility. However, historians of the army and professions in the eighteenth-century claim the upper levels of the army were usually isolated from mobility as the highest ranks were dominated by sons of the aristocracy and landed elite. -

B 46 - Commission of Inquiry Into the Red River Disturbances

B 46 - Commission of inquiry into the Red River Disturbances. Lower Canada RG4-B46 Finding aid no MSS0568 vols. 620 to 621 R14518 Instrument de recherche no MSS0568 Pages Access Mikan no Media Title Label no code Scope and content Extent Names Language Place of creation Vol. Ecopy Dates No Mikan Support Titre Étiquette No de Code Portée et contenu Étendue Noms Langue Lieu de création pages d'accès B 46 - Commission of inquiry into the Red River Disturbances. Lower Canada File consists of correspondence and documents related to the resistance to the settlement of Red River; the territories of Cree and Saulteaux and Sioux communities; the impact of the Red River settlement on the fur trade; carrying places (portage routes) between Bathurst, Henry Bathurst, Earl, 1762-1834 ; Montréal, Lake Huron, Lake Superior, Lake Drummond, Gordon, Sir, 1772-1854 of the Woods, and Red River. File also (Correspondent) ; Harvey, John, Sir, 1778- consists of statements by the servants of 1 folder of 1 -- 1852(Correspondent) ; Loring, Robert Roberts, ca. 5103234 Textual Correspondence 620 RG4 A 1 Open the Hudson's Bay Company and statements textual e011310123 English Manitoba 1815 137 by the agents of the North West Company records. 1789-1848(Correspondent) ; McGillivray, William, related to the founding of the colony at 1764?-1825(Correspondent) ; McNab, John, 1755- Red River. Correspondents in file include ca. 1820(Correspondent) ; Selkirk, Thomas Lord Bathurst; Lord Selkirk; Joseph Douglas, Earl of, 1771-1820(Correspondent) Berens; J. Harvey; William McGillivray; Alexander McDonell; Miles McDonell; Duncan Cameron; Sir Gordon Drummond; John McNab; Major Loring; John McLeod; William Robinsnon, and the firm of Maitland, Garden & Auldjo. -

Guide to Canadian Sources Related to Southern Revolutionary War

Research Project for Southern Revolutionary War National Parks National Parks Service Solicitation Number: 500010388 GUIDE TO CANADIAN SOURCES RELATED TO SOUTHERN REVOLUTIONARY WAR NATIONAL PARKS by Donald E. Graves Ensign Heritage Consulting PO Box 282 Carleton Place, Ontario Canada, K7C 3P4 in conjunction with REEP INC. PO Box 2524 Leesburg, VA 20177 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1: INTRODUCTION AND GUIDE TO CONTENTS OF STUDY 1A: Object of Study 1 1B: Summary of Survey of Relevant Primary Sources in Canada 1 1C: Expanding the Scope of the Study 3 1D: Criteria for the Inclusion of Material 3 1E: Special Interest Groups (1): The Southern Loyalists 4 1F: Special Interest Groups (2): Native Americans 7 1G: Special Interest Groups (3): African-American Loyalists 7 1H: Special Interest Groups (4): Women Loyalists 8 1I: Military Units that Fought in the South 9 1J: A Guide to the Component Parts of this Study 9 PART 2: SURVEY OF ARCHIVAL SOURCES IN CANADA Introduction 11 Ontario Queen's University Archives, Kingston 11 University of Western Ontario, London 11 National Archives of Canada, Ottawa 11 National Library of Canada, Ottawa 27 Archives of Ontario, Toronto 28 Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library 29 Quebec Archives Nationales de Quebec, Montreal 30 McCord Museum / McGill University Archives, Montreal 30 Archives de l'Universite de Montreal 30 New Brunswick 32 Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, Fredericton 32 Harriet Irving Memorial Library, Fredericton 32 University of New Brunswick Archives, Fredericton 32 New Brunswick Museum Archives, -

Canadian Association for Irish Studies 2019 Conference

CANADIAN ASSOCIATION FOR IRISH STUDIES 2019 CONFERENCE IRISH BODIES AND IRISH WORLDS May 29 – June 1 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME John Molson School of Business Conference Centre, 9TH Floor Concordia University 1450 Guy Street, Montreal, Quebec, H3G 1M8 We acknowledge that Concordia University is located on unceded Indigenous lands. The Kanien’kehá:ka Nation is recognized as the custodians of the lands and waters on which we gather today. Tiohtiá:ke/Montreal is historically known as a gathering place for many First Nations. Today, it is home to a diverse population of Indigenous and other peoples. We respect the continued connections with the past, present and future in our ongoing relationships with Indigenous and other peoples within the Montreal community. MAY 29, 2019 Graduate Student Master-Class with Kevin Barry and Olivia Smith 3:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. School of Irish Studies, McEntee Reading Room (1455 boul. De Maisonneuve West, H 1001) Registration & Opening Reception 5:00 p.m. to 6:15 p.m. School of Irish Studies, McEntee Reading Room & Engineering Lab (1455 boul. De Maisonneuve West, H 1001 & H 1067) Exclusive Preview – Lost Children of the Carricks A documentary by Dr. Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin Opening words by His Excellency Jim Kelly Ireland’s Ambassador to Canada and Dr. André Roy Dean of the Faculty of the Arts and Science 6:45 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. (De Sève Cinema, 1400 Boulevard de Maisonneuve West, Ground Floor) MAY 30, 2019 Registration – 9:00 to 9:30 a.m. PANEL 1 – MORNING SESSION – 9:30 a.m. -

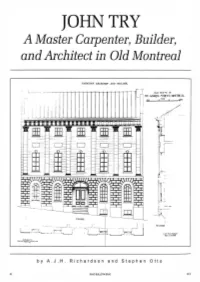

JOHN TRY a Master Carpenter, Builder, and Architect in Old Montreal

JOHN TRY A Master Carpenter, Builder, and Architect in Old Montreal CANADIAN ARCHITEC" AND BUILUER. OUl ltU\ '~1 ·: IS ST. G.\I JI-<!f:l. Sll{l'.t-:T. MON1l{I ':.\L ......____..__''"-"'......__?r-e. _/ ~..,.- ... : ... · ~- . , I I C fril .""'-"" t liunt.'~ M.. \.\oC\., U . ~ by A. J.H. Richardson and Stephen Otto 32 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 22:2 Figure 1 (previous page). House on St Gabriel Street, Montreal, measured and drawn by Cecil Scott Burgess in 1904 and reproduced in the supplement to Csnsdisn Archit1ct snd Buildsr 18, no. 211 (July 1905). This is the house built for David Ross in 1813-.15. (Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library) Figure 2 (left). Watercolour of the interior of Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal, 1852; James Duncan (1806·1881), artist. (McCord Museum of Canadian History, M6015) ohn Try was likely born in 1779 or 1780; when he died suddenly on 14 August 1855, on holiday at Saco near Portland, Maine, he was said to be seventy-five years Jold and a native of England.1 His exact birthplace has not been identified. Nor is it known where he was trained in his trade as a carpenter, although his rapid success in Canada suggests he arrived here well qualified. Try appears to have emigrated to Montreal in 1807. Confirmation for this year is found in a statement he made in 1841: "I have resided in this City thirty-four years."2 More circumstantial evidence exists in an application that David Ross, a lawyer, made in 1814 to the Governor-in-Chief to allow either "Daniel Reynard Architect and Stucco worker," or "--Roots Plasterer and Stucco worker," both of Boston, to enter the province to work on a large house Ross was building in Montreal (figure 1) .3 Vice-regal consent was needed because a state of war still existed between Britain and the United States.