Screen Performers Playing Themselves Matthew Crippen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parking Who Was J 60P NAMES WARREN Gary Cooper

Metro, is still working on the same tator state that she was going to thing cute.” He takes me into the day,* had to dye her brown hair is his six- contract she signed when she was marry Lew Ayres when she gets her television room, and there yellow. Because, Director George wife. Seems to year-old daughter Jerilyn dining Mickey Rooney’s freedom from Ronald Reagan. She Seaton reasoned, "They wouldn't me she rates something new in alone, while at the same time she Hollywood: that’s because have a brunette daughter.” the way of remuneration. says quite interesting, watches a grueling boxing match on Back in Film is from Business, Draft May Take Nancy Guild, now recovered from she hasn’t yet had a date with Lew. the radio. Charles Grapewin retiring Hughes, making pictures when he finishes her session with Orson Welles in John Garfield is doing a Bing Gregory Peck gets Robyt Siod- Kay Thompson’s into two his present film, "Sand,” after 52 “Cagliostro,” goes pictures for his Franchot Tone. mak to direct him in "Great Sinner.” Minus Brilliance of Crosby pal, years in the business. And they Schary Williams Bros. —the Clifton Webb “Belvedere Goes That's a break for them both. He in a bit role in Fran- used to the movies were a By Jay Carmody to College,” and “Bastille” for Wal- appears Celeste Holm and Dan Dailey are say pre- carious ferocious whose last Hollywood Sheilah Graham ter Wanger. chot's picture, “Jigsaw.” both so their Coleen profession! Howard Hughes, the independent By blond, daughter North American Richard under (Released by sensation was production of the stupid, bad-taste "The Outlaw," has Burt Lancaster, thwarted in his Conte, suspension Nina Foch is the only star to beat Townsend, in "Chicken Every Sun- Newspaper Alliance.) at 20thtFox for refusing to work in come up with another that has the movie capital talking. -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

HOLLYWOOD – the Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition

HOLLYWOOD – The Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition Paramount MGM 20th Century – Fox Warner Bros RKO Hollywood Oligopoly • Big 5 control first run theaters • Theater chains regional • Theaters required 100+ films/year • Big 5 share films to fill screens • Little 3 supply “B” films Hollywood Major • Producer Distributor Exhibitor • Distribution & Exhibition New York based • New York HQ determines budget, type & quantity of films Hollywood Studio • Hollywood production lots, backlots & ranches • Studio Boss • Head of Production • Story Dept Hollywood Star • Star System • Long Term Option Contract • Publicity Dept Paramount • Adolph Zukor • 1912- Famous Players • 1914- Hodkinson & Paramount • 1916– FP & Paramount merge • Producer Jesse Lasky • Director Cecil B. DeMille • Pickford, Fairbanks, Valentino • 1933- Receivership • 1936-1964 Pres.Barney Balaban • Studio Boss Y. Frank Freeman • 1966- Gulf & Western Paramount Theaters • Chicago, mid West • South • New England • Canada • Paramount Studios: Hollywood Paramount Directors Ernst Lubitsch 1892-1947 • 1926 So This Is Paris (WB) • 1929 The Love Parade • 1932 One Hour With You • 1932 Trouble in Paradise • 1933 Design for Living • 1939 Ninotchka (MGM) • 1940 The Shop Around the Corner (MGM Cecil B. DeMille 1881-1959 • 1914 THE SQUAW MAN • 1915 THE CHEAT • 1920 WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE • 1923 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS • 1927 KING OF KINGS • 1934 CLEOPATRA • 1949 SAMSON & DELILAH • 1952 THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH • 1955 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS Paramount Directors Josef von Sternberg 1894-1969 • 1927 -

To Download Rupert Christiansen's Interview

Collection title: Behind the scenes: saving and sharing Cambridge Arts Theatre’s Archive Interviewee’s surname: Christiansen Title: Mr Interviewee’s forename(s): Rupert Date(s) of recording, tracks (from-to): 9.12.2019 Location of interview: Cambridge Arts Theatre, Meeting Room Name of interviewer: Dale Copley Type of recorder: Zoom H4N Recording format: WAV Total no. of tracks: 1 Total duration (HH:MM:SS): 00:31:25 Mono/Stereo: Stereo Additional material: None Copyright/Clearance: Assigned to Cambridge Arts Theatre. Interviewer’s comments: None Abstract: Opera critic/writer and Theatre board member, Rupert Christiansen first came the Theatre in 1972. He was a regular audience member whilst a student at Kings College, Cambridge and shares memories of the Theatre in the 1970s. Christiansen’s association was rekindled in the 1990s when he was employed to author a commemorative book about the Theatre. He talks about the research process and reflects on the redevelopment that took place at this time. He concludes by explaining how he came to join the Theatre’s board. Key words: Oxford and Cambridge Shakespeare Company, Elijah Moshinsky, Sir Ian McKellen, Felicity Kendall, Contemporary Dance Theatre, Andrew Blackwood, Judy Birdwood, costume, Emma Thompson, Hugh Laurie, Stephen Fry, Peggy Ashcroft and Alec Guinness, Cambridge Footlights, restaurant, The Greek Play, ETO, Kent Opera and Opera 80, Festival Theatre, Sir Ian McKellen, Eleanor Bron. Picturehouse Cinema, File 00.00 Christiansen introduces himself. His memories of the Theatre range from 1972 to present, he is now on the Theatre’s board of trustees. Christiansen describes his first experience of the Theatre seeing a production of ‘As You Like It’ featuring his school friend Sophie Cox as Celia, by the Oxford and Cambridge Shakespeare Company and directed by Elijah Moshinsky [b. -

Cecil B. Demille's Greatest Authenticity Lapse?

Cecil B. DeMille’s Greatest Authenticity Lapse? By Anton Karl Kozlovic Spring 2003 Issue of KINEMA THE PLAINSMAN (1937): CECIL B. DeMILLE’S GREATEST AUTHENTICITY LAPSE? Cecil B. Demille was a seminal founder of Hollywood whose films were frequently denigrated by critics for lacking historical verisimilitude. For example, Pauline Kael claimed that DeMille had ”falsified history more than anybody else” (Reed 1971: 367). Others argued that he never let ”historical fact stand in the way of a good yarn” (Hogg 1998: 39) and that ”historical authenticity usually took second place to delirious spectacle” (Andrew 1989: 74). Indeed, most ”film historians regard De Mille with disdain” (Bowers 1982: 689)and tended to turn away in embarrassment because ”De Mille had pretensions of being a historian” (Thomas 1975: 266). Even Cecil’s niece Agnes de Mille (1990: 185) diplomatically referred to his approach as ”liberal.” Dates, sequences, geography, and character bent to his needs.” Likewise, James Card (1994: 215) claimed that: ”DeMille was famous for using historical fact only when it suited his purposes. When history didn’t make a good scene, he threw it out.” This DeMillean fact-of-life was also verified by gossip columnist Louella Parsons (1961: 58) who observed that DeMille ”spent thousands of dollars to research his films to give them authenticity. Then he would disregard all the research for the sake of a scene or a shot that appealed to him as better movie-making.” As Charles Hopkins (1980: 357, 360) succinctly put it: ”De Mille did not hesitate -

The Force That Can Be Explained Is Not the True Force

100 / DIALOGUE: A Journal of Mormon Thought cipal issue, there are choices to be below; a fellow bird whom you made between better and worse, can look after and find bugs and bad and better, good and good. seeds for; one who will patch your bruises and straighten your ruffled The truest vision of life I know is that bird in the Venerable Bede feathers and mourn over your that flutters from the dark into a hurts when you accidently fly into lighted hall, and after a while flut- something you can't handle. ters out again into the dark. But Ruth [his wife] is right. It is some- If one can overlook the sexism im- thing—it can be everything—to plicit in this idea, The Spectator Bird is have found a fellow bird with a comforting book in that it reaffirms an whom you can sit among the raf- idea which is the basis for faith: that in ters while the drinking, boating, the end, the best in life will not be at the and reciting and fighting go on mercy of the worst. The Force That Can Be Explained Is Not the True Force BENJAMIN URRUTIA Star Wars; from the Adventures of nemesis, Darth Vader, he bears exactly Luke Skywalker. George Lucas. New the same title, "Dark Lord", as the un- York: Ballantine Books, 1976. 220 pp., seen villain of The Lord of the Rings. $1.95 Tolkien's friend and colleague, C. S. Star Wars. Starring Mark Hamill, Lewis, probably deserves some credit Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, Peter Cush- also. -

A Biography of Gary Cooper Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE LAST HERO : A BIOGRAPHY OF GARY COOPER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Larry Swindell | 394 pages | 16 Dec 2016 | Echo Point Books & Media | 9781626545649 | English | none The Last Hero : A Biography of Gary Cooper PDF Book Cooper was one of the top money-making movie stars of all time. It didn't take long for Cooper to realize that stunt work was challenging and risky. The sport-loving family often went on vacations together, taking frequent trips to Europe. The screen icon learned that some friends of his from Montana were working as extras, and Cooper wanted a piece of the action. He was a three-time Academy Award winner in , and All of these were subsequently played by John Wayne. I called Robert Taylor. His brother Arthur Cooper died in May , at the age of Cooper has undoubtedly left his mark on American culture — besides his Old West good guy persona, he's actually the reason why any male today has the first name "Gary. His wife explained, "Gary loved Southampton. O'Doul certainly aimed some harsh criticism at Cooper, saying, "You throw a ball like an old woman tossing a hot biscuit. I've been coasting along. He worked for five dollars per day as an extra, but that was only to fund an art course he wanted to enroll in. He started to attend Catholic Mass more regularly with his wife and daughter and felt moved spiritually. One Hemingway scholar maintained Papa was profoundly impressed that Cooper was such a stud. While Hemingway was a voracious reader and novelist, Cooper barely picked up a book unless it was a movie script. -

IN the COURT of CRIMINAL APPEALS of TENNESSEE at NASHVILLE January 13, 2021 Session

03/22/2021 IN THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS OF TENNESSEE AT NASHVILLE January 13, 2021 Session STATE OF TENNESSEE v. RONALD LYONS, JAMES MICHAEL USINGER, LEE HAROLD CROMWELL, AUSTIN GARY COOPER, AND CHRISTOPHER ALAN HAUSER Appeal from the Criminal Court for Davidson County Nos. 2017-A-79; 2017-B-1143 Cheryl A. Blackburn, Judge ___________________________________ No. M2019-01946-CCA-R3-CD ___________________________________ Ronald Lyons, James Michael Usinger, Lee Harold Cromwell, Austin Gary Cooper, and Christopher Alan Hauser, Defendants, were named in a 302-count indictment by the Davidson County Grand Jury for multiple counts of forgery and fraudulently filing a lien for their role in filing a total of 102 liens against 42 different individuals with the office of the Tennessee Secretary of State. Defendant Cooper was also named in a second indictment for five additional counts of forgery and five additional counts of fraudulently filing a lien. Prior to trial, Defendant Hauser filed a motion to dismiss for improper venue. Defendants Cromwell and Cooper joined in the motion. The trial court denied the motion after a hearing. After a jury trial, each defendant was convicted as charged in the indictment. The trial court sentenced Defendant Cromwell to an effective sentence of twenty-five years; Defendant Cooper to an effective sentence of fifty years; Defendant Lyons to an effective sentence of twenty-two years; Defendant Usinger to an effective sentence of twenty-one years; and Defendant Hauser to an effective sentence of twenty years. After motions for new trial and several amended motions for new trial were filed, the trial court held a hearing. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

Moab Area Movie Locations Auto Tours – Discovermoab.Com - 8/21/01 Page 1

Moab Area Movie Locations Auto Tours – discovermoab.com - 8/21/01 Page 1 Moab Area Movie Locations Auto Tours Discovermoab.com Internet Brochure Series Moab Area Travel Council The Moab area has been a filming location since 1949. Enjoy this guide as a glimpse of Moab's movie past as you tour some of the most spectacular scenery in the world. All movie locations are accessible with a two-wheel drive vehicle. Locations are marked with numbered posts except for locations at Dead Horse Point State Park and Canyonlands and Arches National Parks. Movie locations on private lands are included with the landowner’s permission. Please respect the land and location sites by staying on existing roads. MOVIE LOCATIONS FEATURED IN THIS GUIDE Movie Description Map ID 1949 Wagon Master - Argosy Pictures The story of the Hole-in-the-Rock pioneers who Director: John Ford hire Johnson and Carey as wagonmasters to lead 2-F, 2-G, 2-I, Starring: Ben Johnson, Joanne Dru, Harry Carey, Jr., them to the San Juan River country 2-J, 2-K Ward Bond. 1950 Rio Grande - Republic Reunion of a family 15 years after the Civil War. Directors: John Ford & Merian C. Cooper Ridding the Fort from Indian threats involves 2-B, 2-C, 2- Starring: John Wayne, Maureen O'Hara, Ben Johnson, fighting with Indians and recovery of cavalry L Harry Carey, Jr. children from a Mexican Pueblo. 1953 Taza, Son of Cochise - Universal International 3-E Starring: Rock Hudson, Barbara Rush 1958 Warlock - 20th Century Fox The city of Warlock is terrorized by a group of Starring: Richard Widmark, Henry Fonda, Anthony cowboys. -

Matthew Mcduffie

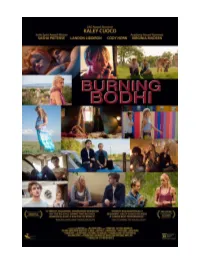

2 a monterey media presentation Written & Directed by MATTHEW MCDUFFIE Starring KALEY CUOCO SASHA PIETERSE CODY HORN LANDON LIBOIRON and VIRGINIA MADSEN PRODUCED BY: MARSHALL BEAR DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: DAVID J. MYRICK EDITOR: BENJAMIN CALLAHAN PRODUCTION DESIGNER: CHRISTOPHER HALL MUSIC BY: IAN HULTQUIST CASTING BY: MARY VERNIEU and LINDSAY GRAHAM Drama Run time: 93 minutes ©2015 Best Possible Worlds, LLC. MPAA: R 3 Synopsis Lifelong friends stumble back home after high school when word goes out on Facebook that the most popular among them has died. Old girlfriends, boyfriends, new lovers, parents… The reunion stirs up feelings of love, longing and regret, intertwined with the novelty of forgiveness, mortality and gratitude. A “Big Chill” for a new generation. Quotes: “Deep, tangled history of sexual indiscretions, breakups, make-ups and missed opportunities. The cinematography, by David J. Myrick, is lovely and luminous.” – Los Angeles Times "A trendy, Millennial Generation variation on 'The Big Chill' giving that beloved reunion classic a run for its money." – Kam Williams, Baret News Syndicate “Sharply written dialogue and a solid cast. Kaley Cuoco and Cody Horn lend oomph to the low-key proceedings with their nuanced performances. Virginia Madsen and Andy Buckley, both touchingly vulnerable. In Cuoco’s sensitive turn, this troubled single mom is a full-blooded character.” – The Hollywood Reporter “A heartwarming and existential tale of lasting friendships, budding relationships and the inevitable mortality we all face.” – Indiewire "Honest and emotionally resonant. Kaley Cuoco delivers a career best performance." – Matt Conway, The Young Folks “I strongly recommend seeing this film! Cuoco plays this role so beautifully and honestly, she broke my heart in her portrayal.” – Hollywood News Source “The film’s brightest light is Horn, who mixes boldness and insecurity to dynamic effect.