Cecil B. Demille and the Art Ofapplied Suggestibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

Movie Mirror Book

WHO’S WHO ON THE SCREEN Edited by C h a r l e s D o n a l d F o x AND M i l t o n L. S i l v e r Published by ROSS PUBLISHING CO., I n c . NEW YORK CITY t y v 3. 67 5 5 . ? i S.06 COPYRIGHT 1920 by ROSS PUBLISHING CO., Inc New York A ll rights reserved | o fit & Vi HA -■ y.t* 2iOi5^ aiblsa TO e host of motion picture “fans” the world ovi a prince among whom is Oswald Swinney Low sley, M. D. this volume is dedicated with high appreciation of their support of the world’s most popular amusement INTRODUCTION N compiling and editing this volume the editors did so feeling that their work would answer a popular demand. I Interest in biographies of stars of the screen has al ways been at high pitch, so, in offering these concise his tories the thought aimed at by the editors was not literary achievement, but only a desire to present to the Motion Picture Enthusiast a short but interesting resume of the careers of the screen’s most popular players, rather than a detailed story. It is the editors’ earnest hope that this volume, which is a forerunner of a series of motion picture publications, meets with the approval of the Motion Picture “ Fan” to whom it is dedicated. THE EDITORS “ The Maples” Greenwich, Conn., April, 1920. whole world is scene of PARAMOUNT ! PICTURES W ho's Who on the Screcti THE WHOLE WORLD IS SCENE OF PARAMOUNT PICTURES With motion picture productions becoming more masterful each year, with such superb productions as “The Copperhead, “Male and Female, Ireasure Island” and “ On With the Dance” being offered for screen presentation, the public is awakening to a desire to know more of where these and many other of the I ara- mount Pictures are made. -

Program, Grauman's Chinese Theatre (Text Transcription)

Program, Grauman’s Chinese Theatre Hollywood, California [cover image: sketch of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre] [page 2, borders decorated with floral designs and Chinese characters] PROGRAMME Grauman’s Chinese Theatre offers “GLORIES OF THE SCRIPTURES” A Sid Grauman Presentation, on the Prologue for Cecil B. De Mille’s “THE KINF OF KINGS” By JEANNIE MACPHERSON Overture Grauman’s Chinese Symphony Orchestra, Arthur Kay conductor, Albert Hay Malotte at the mighty Wurlitzer Organ. Locale – the meeting place of the populace I. Twilight prayers of the common people. II. Dance of the Palms – Theodore Kosloff dancers III. Chant of the Israelite High Priests. “The Holy City” – High Priest Chandowsky. IV. The Boy Soprano – Stewart Brady. TABLEAUX A. Joseph and his Brethren. (Just after his sale into slavery). B. Daniel in the Lion’s Den. C. The Star of Bethlehem. D. The Nativity. E. The Flight Into Egypt. [notes at foot of page 2]: M. Ellis Read, house manager; Lester Cole, stage assistant to Mr. Grauman. Musical Score for “the King of Kings” personally created by Dr. Hugo Reisenfeld; Orchestrations by Otto Potoker. [page 3] “THE KING OF KINGS” CAST • Jesus, the Christ – H.B. Warner • Mary, the Mother – Dorothy Cummings • The Twelve Apostles o Peter – Ernest Torrence o Judas – Joseph Schildkraut o James – James Neill o John – Joseph Striker o Matthew – Robert Edeson o Thomas – Sidney D’Albrook o Andrew – David Imboden o Philip – Charles Belcher o Bartholomew – Clayton Packard o Simon – Roberts Ellsworth o James, the less – Charles Requa o Thaddeus – John T. Prince • Mary Magdalene – Jacqueline Logan • Caiaphas, High Priest of Israel – Rudolph Schildkraut • The Pharisee – Sam DeGrasse • The Scribe – Casson Ferguson • Pontius Pilate, Governor of Judaea – Victor Varconi • Proculla, wife of Pilate – Majel Coleman • The Roman Centurion – Montague Love • Simon of Cyrene – William Boyd • Mark – M. -

Chicago (1927)

Closing Night Gala Sunday 26th March | Screening 20:00 Chicago Dir. Frank Urson & Cecil B.DeMille (uncredited) | USA | 1927 | 1h 58m With: Phyllis Haver, Victor Varconi, Virginia Bradford Performing live: Stephen Horne (piano, accordion) & Frank Bockius (percussion) Chicago is the thoroughly modern tale of a publicity hungry, headline grabbing anti-heroine, as addicted to her own reflection as today’s popular culture is to the Selfie. Roxie Hart is the iconic free-spirited 1920’s flapper transformed into a destructively willful, reckless, self-centred and amoral media darling. Taken to the extreme, she’s the troubling threat to the establishment posed by a generation of young women flaunting social conventions, dress codes and manners, enjoying sexual freedom, self-determination and demanding what they most want out of life. Phyllis Haver (1899-1960) plays Roxie to perfection in a sparkling performance of devious charm, ruthless determination and brilliant comic timing. Tonight is a rare opportunity to rediscover her talent and celebrate the work of an almost forgotten star. Haver began her career in cinema accompanying silent films on piano, became a Mack Sennett Bathing Beauty and then got her big break as an actress, appearing in over 35 films for the Sennett Studios from 1916-20 before signing with DeMille-Pathé. She worked with some of the most revered artists of her day including Buster Keaton, Lon Chaney, Howard Hawks, Raoul Walsh and D.W. Griffith. There’s no doubt that Haver’s star quality and comedic flair elevate Chicago above a simple black and white morality tale. Her career defining performance was praised by critics as “astoundingly fine”, an impressive combination of “comedy and tragedy”. -

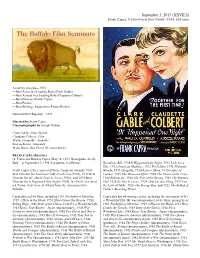

September 3, 2013 (XXVII:2) Frank Capra, IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (1934, 105 Min)

September 3, 2013 (XXVII:2) Frank Capra, IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (1934, 105 min) Academy Awards—1935: —Best Actor in a Leading Role (Clark Gable) —Best Actress in a Leading Role (Claudette Colbert) —Best Director (Frank Capra) —Best Picture —Best Writing, Adaptation (Robert Riskin) National Film Registry—1993 Directed by Frank Capra Cinematography by Joseph Walker Clark Gable...Peter Warne Claudette Colbert...Ellie Walter Connolly...Andrews Roscoe Karns...Shapeley Ward Bond...Bus Driver #1 (uncredited) FRANK CAPRA (director) (b. Francesco Rosario Capra, May 18, 1897, Bisacquino, Sicily, Italy—d. September 3, 1991, La Quinta, California) Broadway Bill, 1934 It Happened One Night, 1933 Lady for a Day, 1932 American Madness, 1932 Forbidden, 1931 Platinum Frank Capra is the recipient of three Academy Awards: 1939 Blonde, 1931 Dirigible, 1930 Rain or Shine, 1930 Ladies of Best Director for You Can't Take It with You (1938), 1937 Best Leisure, 1929 The Donovan Affair, 1928 The Power of the Press, Director for Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), and 1935 Best 1928 Submarine, 1928 The Way of the Strong, 1928 The Matinee Director for It Happened One Night (1934). In 1982 he received Idol, 1928 So This Is Love?, 1928 That Certain Thing, 1927 For a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Film the Love of Mike, 1926 The Strong Man, and 1922 The Ballad of Institute. Fisher's Boarding House. Capra directed 54 films, including 1961 Pocketful of Miracles, Capra also has 44 writing credits, including the screenplay of It’s 1959 A Hole in the Head, 1951 Here Comes the Groom, 1950 a Wonderful Life. -

Moab Area Movie Locations Auto Tours – Discovermoab.Com - 8/21/01 Page 1

Moab Area Movie Locations Auto Tours – discovermoab.com - 8/21/01 Page 1 Moab Area Movie Locations Auto Tours Discovermoab.com Internet Brochure Series Moab Area Travel Council The Moab area has been a filming location since 1949. Enjoy this guide as a glimpse of Moab's movie past as you tour some of the most spectacular scenery in the world. All movie locations are accessible with a two-wheel drive vehicle. Locations are marked with numbered posts except for locations at Dead Horse Point State Park and Canyonlands and Arches National Parks. Movie locations on private lands are included with the landowner’s permission. Please respect the land and location sites by staying on existing roads. MOVIE LOCATIONS FEATURED IN THIS GUIDE Movie Description Map ID 1949 Wagon Master - Argosy Pictures The story of the Hole-in-the-Rock pioneers who Director: John Ford hire Johnson and Carey as wagonmasters to lead 2-F, 2-G, 2-I, Starring: Ben Johnson, Joanne Dru, Harry Carey, Jr., them to the San Juan River country 2-J, 2-K Ward Bond. 1950 Rio Grande - Republic Reunion of a family 15 years after the Civil War. Directors: John Ford & Merian C. Cooper Ridding the Fort from Indian threats involves 2-B, 2-C, 2- Starring: John Wayne, Maureen O'Hara, Ben Johnson, fighting with Indians and recovery of cavalry L Harry Carey, Jr. children from a Mexican Pueblo. 1953 Taza, Son of Cochise - Universal International 3-E Starring: Rock Hudson, Barbara Rush 1958 Warlock - 20th Century Fox The city of Warlock is terrorized by a group of Starring: Richard Widmark, Henry Fonda, Anthony cowboys. -

LAURENCE REID Says

2.S- DECEMBER A BREWSTER MAGAZINE 2 ¢ EILEEN SEDGWICK BesJnr}in£, Tl1e L.-'iensationai Serial E TA THAT €AME TO EA T ,t n upward glance, a spirit of mischief, a "come hither" look- darted from a pair of lovely eyes-all the lovelier because they are fringed by dark, luxuriant lashes. The winsome little co quette brings out the beauty of her eyes by darkening the lashes with WINX and then she worries no more about it, for she knows it is waterproof and will neither run nor smear. Try it yourself. Accentuate the lure of your eyes by darken ing the lashes with WINX. See how much heavier and longer they will seem and how much beauty will be added to your eyes. WINX dries the moment it is applied and one application lasts for days. Absolutely harmless. Brush for applying attached to stopper of bottle. Complete, 75c, black or brown, U. S. and Canada. Mail th.e coupon to-day with 12c for a generous sample of WINX. Another l2c brings a sample of Pert, th.e rouge that won't rub off. ROSS COMPANY 232 West 18~h Street New York Mail rhls COUpOn To·day! ..... .... " , I ' " Add"!! ' . •.. .' " ~:t'l Y:'\:'" C\ £'\ .. _______WINX T.<r.\ +.n ... P '"' c... .. t, .• Advertising Section 3 CECIL B. DE LLE Rising from one triumph to another, now plans a series of pictures to excel anything ever before of/ered- ~9lS: Geraldine Farrar In • Carmen u, a De MilJe ".coop" and a never-to .. be.. forgotten picture, which marked a big .tep forward ill the film indu.trv. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding Aid Prepared by Lisa Deboer, Lisa Castrogiovanni

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding aid prepared by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier and revised by Diana Bowers-Smith. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 04, 2019 Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection , 2006; revised 2008 and 2018. 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 7 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................8 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Highlights.....................................................................................................................................9 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................10 Related Materials ..................................................................................................................................... -

Time Travelers Camporee a Compilation of Resources

1 Time Travelers Camporee A Compilation of Resources Scouts, Ventures, Leaders & Parents…. This is a rather large file (over 80 pages). We have included a “Table of Contents” page to let you know the page numbers of each topic for quick reference. The purpose of this resources to aid the patrols, crews (& adults) in their selection of “Patrol Time Period” Themes. There are numerous amounts of valuable information that can be used to pinpoint a period of time or a specific theme /subject matter (or individual).Of course, ideas are endless, but we just hope that your unit can benefit from the resources below…… This file also goes along with the “Time Traveler” theme as it gives you all a look into a wide variety of subjects, people throughout history. The Scouts & Ventures could possibly use some of this information while working on some of their Think Tank entries. There are more events/topics that are not covered than covered in this file. However, due to time constraints & well, we had to get busy on the actual Camporee planning itself, we weren’t able to cover every event during time. Who knows ? You might just learn a thing or two ! 2 TIME TRAVELERS CAMPOREE PATROL & VENTURE CREW TIME PERIOD SELECTION “RESOURCES” Page Contents 4 Chronological Timeline of A Short History of Earth 5-17 World Timeline (1492- Present) 18 Pre-Historic Times 18 Fall of the Roman Empire/ Fall of Rome 18 Middle Ages (5th-15th Century) 19 The Renaissance (14-17th Century) 19 Industrial Revolution (1760-1820/1840) 19 The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) 19 Rocky Mountain Rendezvous (1825-1840) 20 American Civil War (1861-1865) 20 The Great Depression (1929-1939) 20 History of Scouting Timeline 20-23 World Scouting (Feb.