The Underrepresentation of African Americans and the Role of Casting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duties of a Cinematographer in Creating a Film

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, July 2016, Vol. 6, No. 7, 824-827 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2016.07.013 D DAVID PUBLISHING Duties of a Cinematographer in Creating a Film Ikboljon Melikuziev State Institute of Arts and Culture, Tashkent, Uzbekistan The present article deals with the duties, role and methodical peculiarities of a cinematographer in creating a feature film. The development of creating artistic works in the high creative level and its process is comparatively analyzed within the progress of the Uzbek cinematography. Keywords: cinematographer, film director, critic, image, lightness, recurs, production, picture, plastics, rhythm, composition, editing, scenario, method Introduction The art of cinematography has not been studied widely. It is very difficult to express the description of a film by words. One must see the picture and just for this case a cinematographer’s artistic activity of many years needs careful study. They say, it is not written much about a cameraman’s work yet. In our opinion, the essence of their creativity involves expressing the method, plastics and descriptive decision of a ready feature film. The film supposedly is connected only with the name of a director as a single filmmaker. While criticizing a film they usually speak just about a director and leading actors. You can hardly find anything about a cameraman’s work. Naturally, it is not enough. However, a cameraman’s work spent for artistic picture demands a serious analyses and careful study. Undoubtedly, the right stylistics, artistically completeness of the form which strengthens the effective power of a feature film and accepting the film by the audience depends on the cinematographer’s skills. -

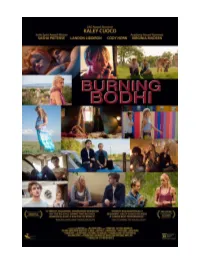

Matthew Mcduffie

2 a monterey media presentation Written & Directed by MATTHEW MCDUFFIE Starring KALEY CUOCO SASHA PIETERSE CODY HORN LANDON LIBOIRON and VIRGINIA MADSEN PRODUCED BY: MARSHALL BEAR DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: DAVID J. MYRICK EDITOR: BENJAMIN CALLAHAN PRODUCTION DESIGNER: CHRISTOPHER HALL MUSIC BY: IAN HULTQUIST CASTING BY: MARY VERNIEU and LINDSAY GRAHAM Drama Run time: 93 minutes ©2015 Best Possible Worlds, LLC. MPAA: R 3 Synopsis Lifelong friends stumble back home after high school when word goes out on Facebook that the most popular among them has died. Old girlfriends, boyfriends, new lovers, parents… The reunion stirs up feelings of love, longing and regret, intertwined with the novelty of forgiveness, mortality and gratitude. A “Big Chill” for a new generation. Quotes: “Deep, tangled history of sexual indiscretions, breakups, make-ups and missed opportunities. The cinematography, by David J. Myrick, is lovely and luminous.” – Los Angeles Times "A trendy, Millennial Generation variation on 'The Big Chill' giving that beloved reunion classic a run for its money." – Kam Williams, Baret News Syndicate “Sharply written dialogue and a solid cast. Kaley Cuoco and Cody Horn lend oomph to the low-key proceedings with their nuanced performances. Virginia Madsen and Andy Buckley, both touchingly vulnerable. In Cuoco’s sensitive turn, this troubled single mom is a full-blooded character.” – The Hollywood Reporter “A heartwarming and existential tale of lasting friendships, budding relationships and the inevitable mortality we all face.” – Indiewire "Honest and emotionally resonant. Kaley Cuoco delivers a career best performance." – Matt Conway, The Young Folks “I strongly recommend seeing this film! Cuoco plays this role so beautifully and honestly, she broke my heart in her portrayal.” – Hollywood News Source “The film’s brightest light is Horn, who mixes boldness and insecurity to dynamic effect. -

The Legality of and Shift in Racial Preferences Within Casting Practices

William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice Volume 26 (2019-2020) Issue 1 First Amendment: Marketplace Morass: Free Speech Jurisprudence and Its Interactions Article 6 with Social Justice November 2019 Who Tells Your Story: The Legality of and Shift in Racial Preferences Within Casting Practices Nicole Ligon Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl Part of the First Amendment Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Repository Citation Nicole Ligon, Who Tells Your Story: The Legality of and Shift in Racial Preferences Within Casting Practices, 26 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 135 (2019), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmjowl/vol26/iss1/6 Copyright c 2020 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl WHO TELLS YOUR STORY: THE LEGALITY OF AND SHIFT IN RACIAL PREFERENCES WITHIN CASTING PRACTICES NICOLE LIGON* INTRODUCTION I. BACKGROUND OF HAMILTON II. TITLE VII AND BFOQ AS APPLIED TO CASTING CALLS III. THE FIRST AMENDMENT AS APPLIED TO HIRING DECISIONS IV. HOW DO PROTECTIONS FOR RACE-BASED CASTING APPLY WHERE CASTING GRANTS PREFERENCE TO WHITE ACTORS AND DISFAVORS MINORITIES? V. ARGUMENTS IN FAVOR OF SUBJECTING CASTING CALLS AND CASTING DECISIONS THAT DISCRIMINATE AGAINST MINORITIES TO LEGAL LIABILITY A. Equity B. Meritocracy VI. TACTICS OUTSIDE THE SCOPE OF LAW REFORM CAN BE MORE EFFECTIVE IN INFLUENCING CASTING PRACTICES A. The Creative Community, Especially Screenwriters, Has the Power to Change Casting Practices B. Audiences Can Help Influence Casting Practices C. Public Recognition May Help Encourage More Equitable Casting Opportunities CONCLUDING THOUGHTS INTRODUCTION When a 2016 casting call1 for the Broadway and touring musical productions of Hamilton specifically sought “non-white men and women ages 20s to 30s,”2 concerns arose regarding its legality. -

Working with Actors | Cilect 1 Sponsors

WORKING WITH ACTORS | CILECT 1 SPONSORS CONTENT Monday 16 November Many thanks to all our sponsors and supporters Conference Registration 6 Tuesday 17 November Keynote Addresses 8 Understanding Acting 12 Workshop 1 16 Workshop 2 18 Workshop 3 20 Workshop 4 22 CILECT Teaching Award 2015 Masterclass 1 24 HFF Tour Presentation 26 Wednesday 18 November Parallel Partner Presentations ADOBE 28 Parallel Partner Presentations ARRI EDC-16 30 Directing Acting 32 Workshop 5 36 Workshop 6 38 Workshop 7 40 Workshop 8 42 CILECT Teaching Award 2015 Masterclass 2 44 CILECT Prize 2015 46 Thursday 19 November CILECT Regional Associations Meetings 50 Perfecting Acting 52 Workshop 9 56 Closing Plenary Discussion 58 CILECT Teaching Award 2015 Masterclass 3 60 ARRI / OSRAM Presentation 62 Friday 20 November Leisure Time Options 64 Addresses 66 2 CILECT | WORKING WITH ACTORS WORKING WITH ACTORS | CILECT 3 Conference Schedule MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY 16 November 2015 17 November 2015 18 November 2015 19 November 2015 20 November 2015 KEYNOTE SPEAKERS PARALLEL PARTNER PRESENTATIONS Introduced by Stanislav Semerdjiev ADOBE CILECT Regional Associations 09.00-10.30 Bettina Reitz – President HFF, Germany Bill Roberts & Michael O’Neill Parallel Meetings Maria Dora Mourão – President CILECT ARRI EDC-16 Andreas Gruber – HFF, Germany Markus Dürr & Peter C. Slansky 10.30-11.00 Coffee Break Coffee Break Coffee Break UNDERSTANDING ACTING DIRECTING ACTING PERFECTING ACTING Presentations & Plenary Discussion Presentations & Plenary Discussion Presentations -

A Look at Race-Based Casting and How It Legalizes Racism, Despite Title VII Laws Latonja Sinckler

Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law Volume 22 | Issue 4 Article 3 2014 And the Oscar Goes to; Well, It Can't Be You, Can It: A Look at Race-Based Casting and How It Legalizes Racism, Despite Title VII Laws Latonja Sinckler Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/jgspl Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Sinckler, Latonja. "And the Oscar Goes to; Well, It Can't Be You, Can It: A Look at Race-Based Casting and How It Legalizes Racism, Despite Title VII Laws." American University Journal of Gender Social Policy and Law 22, no. 4 (2014): 857-891. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sinckler: And the Oscar Goes to; Well, It Can't Be You, Can It: A Look at R AND THE OSCAR GOES TO . WELL, IT CAN’T BE YOU, CAN IT?: A LOOK AT RACE-BASED CASTING AND HOW IT LEGALIZES RACISM, DESPITE TITLE VII LAWS LATONJA SINCKLER I. Introduction ............................................................................................ 858 II. Background ........................................................................................... 862 A. Justifications for Race-Based Casting........................................ 862 1. Authenticity ......................................................................... 862 2. Marketability ....................................................................... 869 B. Stereotyping and Supporting Roles for Minorities .................... 876 III. Analysis ............................................................................................... 878 A. Title VII and the BFOQ Exception ............................................ 878 B. -

P. T. Anderson‟S Dilemma: the Limits of Surrogate Paternity

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Sydney Studies P.T. Anderson's Dilemma P. T. Anderson‟s Dilemma: the Limits of Surrogate Paternity JULIAN MURPHET A while ago now, Fredric Jameson located the Utopian dimension of Coppola‟s first Godfather film (1972) in „the fantasy message projected by the title of this film, that is, in the family itself, seen as a figure of collectivity and as the object of a Utopian longing‟.1 In a late-capitalist America beset by an irreversible „deterioration of the family, the growth of permissiveness, and the loss of authority of the father‟, Coppola‟s Sicilians „project an image of social reintegration by way of the patriarchal and authoritarian family of the past‟. (33) To be sure, the ethnic group may preserve within its anachronistic familial webs a relatively untarnished „Name of the Father‟, that can be trotted out for nostalgic wish-fulfilment on celluloid; but it goes without saying that commercial American cinema has always turned on the institution of the family, to the extent that „in a typical Hollywood product, everything, from the fate of the Knights of the Round Table through the October Revolution up to asteroids hitting the earth, is transposed into an Oedipal narrative‟. 2 Jameson‟s Utopian account of the „ineradicable drive towards collectivity‟ (34) betokened by the family drama in American mass culture surely overlooks that most stubborn obstacle to its realization, both within any given plot, and more practically in everyday life: namely, the father himself. -

Typecasting the Screenwriter Julius Ayodeji Nottingham Trent University UK

To Genre or Not To Genre? Typecasting the Screenwriter Julius Ayodeji Nottingham Trent University UK Abstract: positive reframing of typecasting for the screenwriter. Typecast verb “and don’t worry about being 1. assign (an actor or actress) typecast until you’ve gotten a movie repeatedly to the same type of role, as a made” result of the appropriateness of their Writer, (Go, Big Fish, appearance or previous success in such Charlie’s Angels) John August. roles. (2007) "he tends to be typecast as the caring, intelligent male" Keywords: Storytelling, Authorship, Typecasting, 2. represent or regard (a person or their Characterisation, Psychology role) as fitting a particular stereotype. Introduction Typecasting in the film world is an In his introduction to Augusto Boal’s seminal expression typically applied to the actor. book Games for actors and non-actors This paper will discuss how typecasting translator Adrian Jackson describes for the screenwriter should be seen as a participants in Image Theatre creating a positive shorthand enthusiasm for the series of stills. These groups then suggest titles or themes, before going on to “’sculpt work from that screenwriter that has three-dimensional images under these titles” resonated. (Boal, xix). The psychology of the narrative As a writer for screen and stage myself this surrounding typecasting is ordinarily one idea is analogous of the transition from the as something that should be resisted “if script to screen or page to stage. The thesis you don’t want to be typecast, then you of this paper and the focus of a book being need to fight it every step of the way and developed by its author is that there are a lot never give up.” (Cooper, B. -

FILM ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR At-Large Programmer Wisconsin Union Directorate

FILM ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR At-Large Programmer Wisconsin Union Directorate Accountability: Union Council Report To: WUD Film Director Commitment: Average 8-12 hours weekly Term of Office: May 2020 – May 2021 Monetary Compensation: $30/month Wiscard stipend General Description: The Film Committee is dedicated to the presentation of diverse, challenging programming as well as educational and entertaining films to the University of Wisconsin campus community. The committee also serves as a learning experience for its members regarding the film industry, local film opportunities and leadership roles. The Film Committee researches, plans, coordinates, publicizes and manages up to seven nights of programming a week in the Marquee. The Film Committee also programs an outdoor blockbuster film series during the summer semester. In addition, the Film Committee may offer other special film events, free campus “sneak previews” of major studio releases, the Wisconsin Film Festival, special film series and a variety of other film programs. Associate Director Duties: 1. Aid and oversee WUD Film Committee volunteers in searching for challenging, out of the box programming and oversee volunteers in the programming buckets of HollyWUD (current and classic Hollywood blockbusters), Alternative (independent and documentary films), Marquee After Dark (cult/late night films), International (classic and contemporary international cinema), and special programming. 2. Attend mandatory weekly Film Committee Leadership Team and Film Committee meetings and hold general office hours. 3. Facilitate and oversee weekly subcommittee meeting(s). 4. Administer programming with a comprehensive understanding of fiscal responsibility. Provide overall direction for content and promotion of the program, with assistance from committee members. Offer a presentation of diversity, innovation, and quality in film exhibition. -

Than Digital Makeup: the Visual Effects Industry As Hollywood Diaspora

More Than Digital Makeup: The Visual Effects Industry as Hollywood Diaspora By Sarah K. Hellström Department of Cinema Studies Master’s Thesis 15 hp Master Course 30 hp, VT 2013 Supervisor: Dr. Patrick Vonderau If I hear one more person who comes up to me and complains about [how]‘computer-music has no soul’ then I will go furious, you know. ‘Cause of course the computer is just a tool. And if there is no soul in computer-music then it's because nobody put it there and that's not the computers role, it's the role of the songwriter. He puts down his soul in the song if he wants to. A guitar will never write a song and a computer will never write a song, these are just tools.i - Björk Title: More Than Digital Makeup: The Visual Effects Industry as Hollywood Diaspora Author’s name: Sarah K. Hellström Supervisor: Dr. Patrick Vonderau Abstract This thesis assesses the marginal field (niche unit) of visual effects while taking into account visible and invisible vfx in virtual and actual geographies in Hollywood movies as part of industry-level studies, all the while seeking to bridge the gap between traditional, theoretical approaches of cinema studies and practitioner experience in the context of production culture. The focus of this essay remains on the many temporal aspects of production processes that identify vfx film production as chief, and vfx for television as subsequential. Encouraging scholars to consider a previously limited and repeatedly mislabeled area by demonstrating the pandemic presence of effects and its workers as a form of Hollywood diaspora, this thesis also seeks to demonstrate the need for involvement by means of scholar-practitioner methodologies. -

From the Camera Obscura to Video Assist Author(S): Jean-Pierre Geuens Source: Film Quarterly, Vol

Through the Looking Glasses: From the Camera Obscura to Video Assist Author(s): Jean-Pierre Geuens Source: Film Quarterly, Vol. 49, No. 3 (Spring, 1996), pp. 16-26 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1213467 . Accessed: 15/06/2011 09:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucal. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Film Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org Through Jean-Pierre Geuens the Looking Glasses From the Camera Obscura to Video Assist The oriiginal video assist apparatus put tog;ether by Bruce Hill in 1970 The studio is finally quiet. -

Film Director Agreement (Fiction Film)

FILM DIRECTOR AGREEMENT (FICTION FILM) The Parties to this Agreement are: ___________________ , personal identity code _________, address _____________________________ (hereinafter the ”Director”); and ___________________ , company identity code _________, address _____________________________ (hereinafter the ”Producer”). 1. OBJECT OF THE AGREEMENT 1.1 The Producer will employ the Director for making the film _____________________ (hereinafter the ”Film”) in accordance with the terms and conditions agreed in this Film Director Agreement (hereinafter the ”Agree- ment”). 1.2 The Film will be filmed in ________ format, and its screen time is fixed at ______ minutes. 1.3 The target age limit for the Film shall be ______. 1.4 The production budget for the Film is ___________________ euros. 1.5 The Film shall be based on: a) ________ʼs literary or other work entitled ”______________”. The film rights in respect of the work have been transferred under a separate agreement between the Producer and the holder of the rights. b) Original idea by _________ The manuscript for the Film has been made by: _________________________. The film rights in respect of the manuscript have been transferred under a sepa- rate agreement between the Producer and the holder of the rights. 2. THE DIRECTORʼS JOB DESCRIPTION 2.1 The employment of the Director begins / has begun on ___.___.20___. 1 The Directorʼs work shall be conducted as follows: Preliminary planning between ________ - ________, in total __ days; Filming period between ________ - ________, in total __ days; Post-production work between ________ - ________, in total __ days. The Directorʼs employment will end once the Director has inspected and ap- proved the final form of the Film. -

Dga Independent Filmmakers

Ti West directing In a Valley of Violence INDEPENDENTDGA FILMMAKERS Nicole Holofcener directing Enough Said Dee Rees directing Mudbound It’s YOUR film. The Directors Guild of America is a powerful force that can help you realize your Rodrigo Garcia directing Last Days in the Desert vision regardless of budget. Find out what the DGA is all about. Ryan Coogler directing Creed GREETINGS FROM DGA PRESIDENT THOMAS SCHLAMME Dear Filmmaker: What is independent filmmaking today? Traditionally, independent We support our members working in independent film by films are those that are produced outside of the studio system. More protecting their rights, as well as providing them with the realistically, in the current landscape, with streaming services, day and flexibility to do projects they are passionate about. The Guild’s date releases and ever-changing distribution models, independent has Independent Directors Committees are a concrete embodiment taken on a feeling of otherness – something not mainstream. of this commitment. These Committees – one based in New York and the other based in Los Angeles – host regular gatherings for And here you are. You’ve made a movie that caught attention and it’s independent and low-budget directors. The Committees have playing at a festival or maybe you’ve been lucky enough to secure a also established the very successful Director’s Finder Screening distribution deal. As a director, you may think your responsibilities end Series, which regularly showcases unreleased independent films once the film is completed. Ideally, you’ve handled every creative choice directed by DGA members for an audience of independent during pre-production, through production and into post.