The Necessity of a Holistic Peace Building Approach for Effective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Get Study Material on Whatsapp, Send Your Name and City on Whatsapp No

To get study material on Whatsapp, send your Name and City on Whatsapp no. 75972-40000 https://prepmate.in/books/ https://telegram.me/upscprepmate To get study material on Whatsapp, send your Name and City on Whatsapp no. 75972-40000 https://prepmate.in/books/ https://telegram.me/upscprepmate To get study material on Whatsapp, send your Name and City on Whatsapp no. 75972-40000 Table of Contents Polity And Governance ....................................................................................................................... 1 1. Cutting down tribunals (Relevant for GS Prelims, GS Mains Paper II) ............................... 1 2. SC allows abortion of ailing foetus (Relevant for GS Mains Paper II) ................................ 1 3. SC open to liquor sale on city highways (Relevant for GS Prelims, GS Mains Paper II) ............................................................................................................................................................................ 3 4. Selection of ECs must be transparent, SC tells Centre (Relevant for GS Prelims, GS Mains Paper II) ........................................................................................................................................... 4 5. Presidential Election, 2017 – Right to vote or not to vote (Relevant for GS Prelims, GS Mains Paper II) ........................................................................................................................................... 5 6. National Pension Service fortnight (Relevant for -

In/Security in Context: an Inquiry Into the Relational and Contextual Dimensions of In/Security Within

IN/SECURITY IN CONTEXT An inquiry into the relational and contextual dimensions of in/security within the Colombian peace process A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2017 Caroline Delgado School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Table of Contents List of Maps .......................................................................................................................... 8 List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ 8 List of Acronyms .................................................................................................................. 9 Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 11 Declaration .......................................................................................................................... 12 Copyright Statement .......................................................................................................... 13 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. 14 Dedication ........................................................................................................................... 15 CHAPTER ONE: Introduction ........................................................................................ 17 1.1 An Abstract of Everyday -

Bee Round 3 Bee Round 3 Regulation Questions

NHBB Nationals Bee 2018-2019 Bee Round 3 Bee Round 3 Regulation Questions (1) This man's alleged last words were \The battle is at its height - wear my armor and beat my war drums. Do not announce my death." After his death, this man was given the title Chunmugong. A double agent plot led to the removal of this man in favor of a commander who was decisively defeated at the Battle of Chilchonryang. This man was killed during his final victory at the Battle of Noryang, after he defeated 330 Japanese ships with 13 at the Battle of Myeongnyang. For the point, name this \Nelson of the East", a Korean admiral who championed turtle ships. ANSWER: Yi Sun-Sin (2) A politician with this surname, the rival of Dave Pearce, had an affair with burlesque performer Blaze Starr. The Wall Street Journal, jokingly labeled a politician with this surname the \fourth branch of government" due to the immense power he wielded as chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. That man's father, another politician with this surname, was assassinated by Carl Weiss. The \Share Our Wealth Plan", which called for making \Every Man A King", was formulated by a member of, for the point, what Louisiana political dynasty whose members included Earl, Russell, and Huey? ANSWER: Long (accept Earl Long; accept Russell Long; accept Huey Long) (3) This region's inhabitants launched raids against its northern neighbors, called \harvesting the steppes," to fuel its slave trade, which was based out of Kefe. Haci Giray [ha-ji ge-rai] established this region's namesake khanate after breaking off from the Golden Horde. -

The Project of Land Restitution in Colombia: an Illustration of the Civilizing Force of Hypocrisy? Revista Estudios Socio-Jurídicos, Vol

Revista Estudios Socio-Jurídicos ISSN: 0124-0579 [email protected] Universidad del Rosario Colombia Saffon, Maria Paula The Project of Land Restitution in Colombia: An Illustration of the Civilizing Force of Hypocrisy? Revista Estudios Socio-Jurídicos, vol. 12, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2010, pp. 109-194 Universidad del Rosario Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=73315636005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative The Project of Land Restitution in Colombia: An Illustration of the Civilizing Force of Hypocrisy? Maria Paula Saffon* Columbia University, New York, EEUU. Fecha de recepción: 23 de julio de 2010 Fecha de aceptación: 23 de agosto de 2010 ABSTRACT This article offers a theoretical interpretation of the dis- positions on land restitution contained in the famous “Victims’ Bill”, which was debated in the Colombian Congress during the year 2008. The bill included specific mechanisms aimed at guaranteeing the restitution of land to victims of the Colombian armed conflict. At the time, the bill was endorsed by all the main politi- cal actors in the country –notably the government and the elites that support it, on the one hand, and victims’ and human rights organizations and other opposition groups, on the other–. The fact that the restitution of land to victims of the Colombian armed conflict was being considered as a serious possibility by all political actors in the country seemed to indicate the existence of a consensus among actors whose positions are ordinarily opposed, on an issue that has traditionally led to high levels of polarization. -

Revista Universitaria De Historia Militar Volumen 8, Nº 17

2019 ISSN 2254-6111 RUHM Revista Universitaria de Historia Militar Volumen 8, Nº 17 Dossier TERRORISMO DE ESTADO EN LATIONAMÉRICA DURANTE LA SEGUNDA MITAD DEL SIGLO XX Estudios Traducción La milicia concejil de Teruel (Baja Edad Media) Obligaciones militares en los archivos de Mari (s. XIX a. C.) Los caballeros de la Orden de Malta Ensayo El armamento de las guerras civiles yoruba Sobre las guerras civiles El sistema antiaéreo republicano en la Guerra Civil Reseñas La "justicia" de Franco en Calera y Chozas Centro de Estudios de la Guerra R Revista Universitaria de Historia Militar La RUHM está recogida e indexada en ERIHPLUS, Base de datos ISOC, Latindex, DOAJ, MIAR (ISDC 9,3), REBID, CIRC, Sherpa/Romeo, Google Scholar Metric, Dialnet, Sistema de Evaluación de revistas del CONICET (Grupo A), Fuente Academia Plus de la ESCBO, Emerging Sources Citation Index Web of Science Thomson Reuters y el sello de calidad del FECYT. © Centro de Estudios de la Guerra-RUHM (Teruel, España), 2019. EDITA. Centro de Estudios de la Guerra-RUHM (Teruel, España) Revista Universitaria de Historia Militar ISSN: 2254 – 6111 http://ruhm.es Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ruhm.es Twitter: @ruhm_online E–mail: [email protected] IMAGEN DE PORTADA. “Soldados mexicanos en las calles” (30 de julio de 1968). Fotografía de Marcel·li Perelló La Revista Universitaria de Historia Militar es una publicación científica de carácter semestral editada por el Centro de Estudios de la Guerra-RUHM. Esta revista no se identifica necesariamente con los contenidos aquí incluidos. Queda prohibida la reproducción total y/o parcial de cualquier contenido de la revista sin la autorización expresa y por escrito de la dirección. -

Overseas 2017

overSEAS 2017 This thesis was submitted by its author to the School of English and American Studies, Eötvös Loránd University, in partial ful- filment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts. It was found to be among the best theses submitted in 2017, therefore it was decorated with the School’s Outstanding Thesis Award. As such it is published in the form it was submitted in overSEAS 2017 (http://seas3.elte.hu/overseas/2017.html) ALAPSZAKOS SZAKDOLGOZAT Szrogh Bence Anglisztika alapszak Angol szakirány 2017 CERTIFICATE OF RESEARCH By my signature below, I certify that my ELTE B.A. thesis, entitled US-Colombian Relations and the War on Drugs is entirely the result of my own work, and that no degree has previously been conferred upon me for this work. In my thesis I have cited all the sources (printed, electronic or oral) I have used faithfully and have always indicated their origin. The electronic version of my thesis (in PDF format) is a true representation (identical copy) of this printed version. If this pledge is found to be false, I realize that I will be subject to penalties up to and including the forfeiture of the degree earned by my thesis. Date: 18/04/2017 Signed: ........................................................... EÖTVÖS LORÁND TUDOMÁNYEGYETEM Bölcsészettudományi Kar ALAPSZAKOS SZAKDOLGOZAT Amerikai-kolumbiai kapcsolatok és a drogellenes háború US-Colombian Relations and the War on Drugs Témavezető: Készítette: Dr. Szabó Éva Eszter Szrogh Bence egyetemi adjunktus anglisztika alapszak angol szakirány 2017 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 I. The Beginnings of US Influence in Colombia From the Monroe Doctrine to the Beginning of the Cold War .................................... -

The Project of Land Restitution in Colombia: an Illustration of the Civilizing Force of Hypocrisy?

The Project of Land Restitution in Colombia: An Illustration of the Civilizing Force of Hypocrisy? Maria Paula Saffon* Columbia University, New York, EEUU. Fecha de recepción: 23 de julio de 2010 Fecha de aceptación: 23 de agosto de 2010 ABSTRACT This article offers a theoretical interpretation of the dis- positions on land restitution contained in the famous “Victims’ Bill”, which was debated in the Colombian Congress during the year 2008. The bill included specific mechanisms aimed at guaranteeing the restitution of land to victims of the Colombian armed conflict. At the time, the bill was endorsed by all the main politi- cal actors in the country –notably the government and the elites that support it, on the one hand, and victims’ and human rights organizations and other opposition groups, on the other–. The fact that the restitution of land to victims of the Colombian armed conflict was being considered as a serious possibility by all political actors in the country seemed to indicate the existence of a consensus among actors whose positions are ordinarily opposed, on an issue that has traditionally led to high levels of polarization. This consensus is quite puzzling, because it seems to be at odds with the interests and/or the conceptions of justice advocated by these political ac- tors, and because the restitution of land faces enormous Para citar este artículo: Saffon, Maria Paula, “The Project of Land Restitution in Colombia: An Illustration of the Civilizing Force of Hypocrisy?”, Revista Estudios Socio-Jurídicos, 2010, 12,(2), pp. 109-194. * Ph.D. Candidate, Columbia University, Political Science Department. -

War Crimes Prosecution Watch, Vol. 15, Issue 10

PILPG Logo Case School of Law Logo War Crimes Prosecution Watch Editor-in-Chief David Krawiec FREDERICK K. COX Volume 15 - Issue 10 INTERNATIONAL LAW CENTER July 4, 2020 Technical Editor-in-Chief Erica Hudson Founder/Advisor Michael P. Scharf Managing Editors Alexander Peters Faculty Advisor Matthew Casselberry Jim Johnson War Crimes Prosecution Watch is a bi-weekly e-newsletter that compiles official documents and articles from major news sources detailing and analyzing salient issues pertaining to the investigation and prosecution of war crimes throughout the world. To subscribe, please email [email protected] and type "subscribe" in the subject line. Opinions expressed in the articles herein represent the views of their authors and are not necessarily those of the War Crimes Prosecution Watch staff, the Case Western Reserve University School of Law or Public International Law & Policy Group. Contents AFRICA NORTH AFRICA Libya Libya: UN Establishes Fact Finding Body; A Step Toward Accountability (Human Rights Watch) CENTRAL AFRICA Central African Republic Sudan & South Sudan Trial of Alleged Sudan War Criminal Sends Strong Signal, Prosecutor says (Voice of America) Democratic Republic of the Congo Twenty civilians killed in attacks on northeastern Congo villages (Reuters) UN condemns killing of Indonesian peacekeeper in DR Congo (UN News) UNHCR appalled at rising violence against displaced in eastern DRC (Relief Web) WEST AFRICA Côte d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast) Ivorian Ex-Minister Appeals to Return Home as ICC Hearing Looms (Bloomberg) -

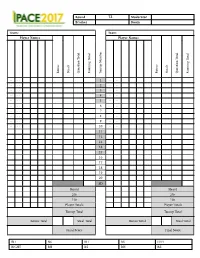

Round Moderator Bracket Room Team

Round 13 Moderator Bracket Room Team: Team: Player Names Player Names Steals Bonus Steals Question Total Running Total Bonus Running Total Tossup Number Question Total .. .. 1 .. .. .. .. 2 .. .. .. .. 3 .. .. .. .. 4 .. .. .. .. 5 .. .. .. .. 6 .. .. .. .. 7 .. .. .. .. 8 .. .. .. .. 9 .. .. .. .. 10 .. .. 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 SD Heard Heard 20s 20s 10s 10s Player Totals Player Totals Tossup Total Tossup Total Bonus Total Steal Total Bonus Total Steal Total Final Score Final Score RH RS BH BS LEFT RIGHT BH BS RH RS PACE NSC 2017 - Round 13 - Tossups 1. None of the title group of these people pay attention to a devotional image of Mary hanging on a tree on the right-hand side of a painting depicting these people at a kermis. In that painting, one of these people with a peacock feather in his hair looks intently at the bagpipe player seated next to him. Another painting titled for these people shows two wheat sheaves held together by a rake above a man with a spoon in his hat. In a painting titled for these people, two of them carry some (*) soup on an unhinged door. Vienna's Kunsthistorisches (KOONST-hiss-TOR-ish-is) Museum has a painting of these people dancing by an artist who showed a paper-crowned bride not feasting in another painting of them. For 10 points, a genre painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder depicts a wedding attended by what lower-class people? ANSWER: peasants [accept The Peasant Dance or The Peasant Wedding; prompt on farmers; prompt on serfs; prompt on things such as poor people] <Bentley> 2. -

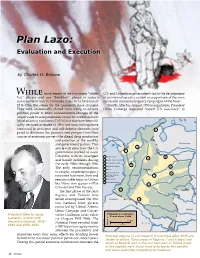

Plan Lazo: Evaluation and Execution

Plan Lazo: Evaluation and Execution by Charles H. Briscoe While involvement of the two major “white- U.S. and Colombian governments led to the development hat” players and one “black-hat” player in today’s of an internal security system to support one of the most narco-terrorist war in Colombia dates to La Violencia of successful counterinsurgency campaigns of the time.1 1948–1966, the stakes for the insurgents have changed. Shortly after his August 1958 inauguration, President They have dramatically shifted from trying to achieve Lleras Camargo requested “expert U.S. assistance” to political power to effect socioeconomic changes in the countryside to using economic power to control sociopo- litical affairs in rural areas.La Violencia may have been offi- cially declared as ended in 1966, but mass killings have continued as insurgent and self-defense elements com- 3 peted to dominate the peasants and prosper from their source of economic power—the illegal drug production and extortion of the wealthy Panama and government justices. This Venezuela article will show how the U.S. 2 government worked to assist 1 Colombia with its insurgent 1 Urabá-Darien 6 4 and bandit problems during 2 Caribe-Since-San Jorge 3 Serranía del Perijá the early 1960s through 1966. 5 4 Magdalena Medio 8 The early recommendations 5 Pacific Bogotá to employ counterinsurgency 6 Saravena-Arauca 8 Andean Orinoco Colombia measures had merit then and 7 Piedmont 7 remain viable today in Colom- 8 Ariarí-Meta 9 Caquetá-Putumayo bia. Many now appear in Plan 8 Colombia and Plan Patriota. -

Welcome to the Jungle: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Colombia

Welcome to the Jungle Counterinsurgency Lessons from Colombia A Contemporary Battlefield Assessment Lionel Beehner Liam Collins by the Modern War Institute May 23, 2019 Welcome to the Jungle: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Colombia Table of Contents Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary..................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 9 Chapter I – History of the War ................................................................................................................. 13 The Insurgency ...................................................................................................................................... 14 The Peace Process ................................................................................................................................. 17 Chapter II – Causes of the Conflict .......................................................................................................... 21 Structural Conditions ............................................................................................................................ 22 Drivers of Violence ............................................................................................................................... -

2016 Delgado Jorge Eduardo 1041615 Ethesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ COUNTER-INSURGENCY IN COLOMBIA THE ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION OF A MILITARY STRATEGIC TRADITION Delgado, Jorge Eduardo Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 COUNTER-INSURGENCY IN COLOMBIA: THE ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION OF A MILITARY STRATEGIC TRADITION By Jorge Eduardo Delgado Supervised by Professor Michael Rainsborough A thesis presented for the degree of Department of War Studies Doctor of Philosophy in War Studies King’s College London May 2016 1 ABSTRACT This research proposes to examine the composition and evolution of the Colombian military’s approach to counter-insurgency since the origins of the internal armed conflict that affects the country.