Security Vulnerabilities in Open Source Electronic Design Automation Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sun Storage 16 Gb Fibre Channel Pcie Host Bus Adapter, Emulex Installation Guide for HBA Model 7101684

Sun Storage 16 Gb Fibre Channel PCIe Host Bus Adapter, Emulex Installation Guide For HBA Model 7101684 Part No: E24462-10 August 2018 Sun Storage 16 Gb Fibre Channel PCIe Host Bus Adapter, Emulex Installation Guide For HBA Model 7101684 Part No: E24462-10 Copyright © 2017, 2018, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, then the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT END USERS: Oracle programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, delivered to U.S. Government end users are "commercial computer software" pursuant to the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation and agency-specific supplemental regulations. As such, use, duplication, disclosure, modification, and adaptation of the programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, shall be subject to license terms and license restrictions applicable to the programs. -

Amateur Radio Software Distributed with (X)Ubuntu LTS Serge Stroobandt, ON4AA

Amateur Radio Software Distributed with (X)Ubuntu LTS Serge Stroobandt, ON4AA Copyright 2014–2018, licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA Introduction Amateur radio (also called “ham radio”), is a technical hobby Many ham radio stations are highly integrated with computers. Radios are interfaced with com- puters to aid with contact logging, propagation prediction, station spotting, antenna steering, signal (de)modulation and filtering. For many years, amateur radio software has been a bastion of Windows™ ap- plications developed by However, with the advent of the Rasperry Pi, amateur radio hobbyists are slowly but surely discovering GNU/Linux. Most of the software for GNU/Linux is available through package repositories. Such package repositories come by default with the GNU/Linux distribution of your choice. Package management systems offer many benefits in the form of security (you know what you are getting from whom) and ease-of-use (packages are upgraded automatically). No longer does one need to wander the back corners of the internet to find wne or updated software, exposing oneself to the risk of catching a computer virus. A number of GNU/Linux distributions offer freely installable ham-related packages under the “Amateur Radio” section of their main repository. The largest collection of ham radio packages is offeredy b OpenSuse and De- bian-derived distributions like Xubuntu LTS and Linux Mint, to name but a few. Arch Linux may also have whole bunch of ham related software in the Arch User Repository (AUR). 1 Synaptic One way to find and tallins ham radio packages on Debian-derived distros is by using the Synaptic graphical package manager (see Figure 1). -

PLM Weekly Summary Editor: Cimdata News Team 15 January 2021 Contents Cimdata News

PLM Weekly Summary Editor: CIMdata News Team 15 January 2021 Contents CIMdata News ............................................................................................................................................ 2 An Enterprise Digital Transformation Platform – a CIMdata Commentary......................................................2 Aras’ Cloud Strategy – a CIMdata Blog Post ....................................................................................................5 CIMdata Announces its 2021 PLM Market & Industry Forum Series ..............................................................6 CIMdata to Host a Free Webinar on CAD Trends ............................................................................................7 NLign Analytics “Structural Lifecycle Digital Environment” Enables Model-Driven Product Quality – a CIMdata Commentary .......................................................................................................................................8 PTC’s Cloud Strategy – a CIMdata Blog Post ................................................................................................. 13 Acquisitions .............................................................................................................................................. 14 Accenture Acquires Real Protect, Brazil-Based Information Security Company ........................................... 14 Atos to acquire In Fidem to reinforce its cybersecurity position in the North American market .................... 15 Planview -

Simulation Software for Online Teaching of ECE Courses

Paper ID #25855 Simulation Software for Online Teaching of ECE Courses Dr. Alireza Kavianpour, DeVry University, Pomona Dr. Alireza Kavianpour received his PH.D. Degree from University of Southern California (USC). He is currently Senior Professor at DeVry University, Pomona, CA. Dr. Kavianpour is the author and co-author of over forty technical papers all published in IEEE Journals or referred conferences. Before joining DeVry University he was a researcher at the University of California, Irvine and consultant at Qualcom Inc. His main interests are in the areas of embedded systems and computer architecture. c American Society for Engineering Education, 2019 Simulation software for Online teaching of ECE Courses ABSTRACT Online learning, also known as e-learning, has become an increasingly common choice for many students pursuing an education. Online learning requires the student to participate and learn virtually via computer, as opposed to the traditional classroom environment. Although online learning is not for everyone, it's important for prospective students to determine whether or not it's something they would like to pursue. The following are advantages and disadvantages for online learning: Advantages -Online learning provides flexibility because students are able to work when it's convenient for them. Students can do all the homework from any location as long as they have access to a computer. -A student can learn at his or her own pace. -Degrees can be completed in less time compared to traditional universities. -Students have fewer distractions, and it can be less intimidating to participate in the discussions. -Students have the opportunity to connect with and work alongside students from other locations. -

Eagle Tutorial

EAGLE EASILY APPLICABLE GRAPHICAL LAYOUT EDITOR Tutorial Version 5 Schematic – Layout – Autorouter for Linux® Mac® Windows® CadSoft Computer www.cadsoftusa.com 6th Edition 005175100 Copyright © 2010 CadSoft Computer All Rights Reserved CadSoft Computer is a trading division of Newark Corporation. If you have any questions please feel free to contact us: USA and other countries: Phone: +1 (954) 237 0932 Fax: +1 (954) 237 0968 Internet: www.cadsoftusa.com Email: [email protected] Germany and other European countries: Phone: +49 (0)8635 6989-10 Hotline: +49 (0)8635 6989-30 Fax: +49 (0)8635 6989-40 Internet: www.cadsoft.de Email: [email protected] And remember that we offer a free hotline for our customers! Copyright 2010 CadSoft Computer. All rights reserved worldwide. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, digitizing, or otherwise, without the prior consense of CadSoft Computer. Printing this tutorial for your personal use is allowed. Windows is a registered trademark of Microsoft Corporation. Linux is a registered trademark of Linus Torvalds. Mac is a registered trademark of Apple Computer Inc. Table Of Contents 1 What to expect from this Tutorial...............................................................6 2 Features of EAGLE.......................................................................................7 System Requirements...............................................................................7 -

Circuitmaker 2000 (The Symbol Will Be Replaced by a Rectangle)

CircuitMaker® 2000 the virtual electronics lab™ CircuitMaker User Manual advanced schematic capture mixed analog/digital simulation Revision A Software, documentation and related materials: Copyright © 1988-2000 Protel International Limited. All Rights Reserved. Unauthorized duplication of the software, manual or related materials by any means, mechanical or electronic, including translation into another language, except for brief excerpts in published reviews, is prohibited without the express written permission of Protel International Limited. Unauthorized duplication of this work may also be prohibited by local statute. Violators may be subject to both criminal and civil penalties, including fines and/or imprisonment. CircuitMaker, TraxMaker, Protel and Tango are registered trademarks of Protel International Limited. SimCode, SmartWires and The Virtual Electronics Lab are trademarks of Protel International Limited. Microsoft and Microsoft Windows are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. Orcad is a registered trademark of Cadence Design Systems. PADS is a registered trademark of PADS Software. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Printed by Star Printery Pty Ltd ii Table of Contents Chapter 1: Welcome to CircuitMaker Introduction............................................................................................1-1 Required User Background..............................................................1-1 Required Hardware/Software...........................................................1-1 -

Experiences in Using Open Source Software for Teaching Electronic Engineering CAD

Experiences in Using Open Source Software for Teaching Electronic Engineering CAD Dr Simon Busbridge1 & Dr Deshinder Singh Gill School of Computing, Engineering and Mathematics, University of Brighton, Brighton BN2 4GJ [email protected] Abstract Embedded systems and simulation distinguish modern professional electronic engineering from that learnt at school. First year undergraduates typically have little appreciation of engineering software capabilities and file handling beyond elementary word processing. This year we expedited blended teaching through the experiential based learning process via open source engineering software. Students engaged with the entire electronic engineering product creation process from inception, performance simulation, printed circuit board design, manufacture and assembly, to cabinet design and complete finished product. Currently students learn software skills using a mixture of electronic and mechanical engineering software packages. Although these have professional capability they are not available off-campus and are sometimes surprisingly poor in simulating real world devices. In this paper we report use of LTspice, FreePCB and OpenSCAD for the learning and teaching of analogue electronics simulation and manufacture. Comparison of the software options, the type of tasks undertaken, examples of student assignments and outputs, and learning achieved are presented. Examples of assignment based learning, integration between the open source packages and difficulties encountered are discussed. Evaluation of student attitudes and responses to this method of learning and teaching are also discussed, and the educational advantages of using this approach compared to the use of commercial packages is highlighted. Introduction Most educational establishments use software for simulating or designing engineering. Most commercial packages come with an academic licence which restricts access to on-site computers. -

IDF Exporter IDF Exporter Ii

IDF Exporter IDF Exporter ii April 27, 2021 IDF Exporter iii Contents 1 Introduction to the IDFv3 exporter 2 2 Specifying component models for use by the exporter 2 3 Creating a component outline file 4 4 Guidelines for creating outlines 6 4.1 Package naming ................................................ 6 4.2 Comments .................................................... 6 4.3 Geometry and Part Number entries ...................................... 7 4.4 Pin orientation and positioning ........................................ 7 4.5 Tips on dimensions ............................................... 8 5 IDF Component Outline Tools 8 5.1 idfcyl ....................................................... 9 5.2 idfrect ...................................................... 10 5.3 dxf2idf ...................................................... 11 6 idf2vrml 12 IDF Exporter 1 / 12 Reference manual Copyright This document is Copyright © 2014-2015 by it’s contributors as listed below. You may distribute it and/or modify it under the terms of either the GNU General Public License (http://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html), version 3 or later, or the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/), version 3.0 or later. All trademarks within this guide belong to their legitimate owners. Contributors Cirilo Bernardo Feedback Please direct any bug reports, suggestions or new versions to here: • About KiCad document: https://gitlab.com/kicad/services/kicad-doc/issues • About KiCad software: https://gitlab.com/kicad/code/kicad/issues • About KiCad software i18n: https://gitlab.com/kicad/code/kicad-i18n/issues Publication date and software version Published on January 26, 2014. IDF Exporter 2 / 12 1 Introduction to the IDFv3 exporter The IDF exporter exports an IDFv3 1 compliant board (.emn) and library (.emp) file for communicating mechanical dimensions to a mechanical CAD package. -

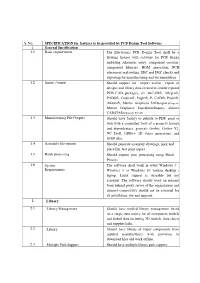

S. No. SPECIFICATION for Features to Be Provided by PCB Design Tool

S. No. SPECIFICATION for features to be provided by PCB Design Tool Software 1 General Specification 1.1 Basic requirements The Electronics PCB Design Tool shall be a floating license with software for PCB design including schematic entry, component creation, component libraries, BOM generation, PCB placement and routing, ERC and DRC checks and exporting for manufacturing and documentation. 1.2 Import / export Should support for import and/or export of designs and library data created in similar reputed PCB CAD packages, viz. OrCAD®, Allegro®, PADS®, Cadstar®, Eagle®, P- CAD®, Protel®, Altium®, Mentor Graphics® DxDesigner®(Import), Mentor Graphics® Expedition(Import), Zuken® CADSTAR®(Import), P-CAD 1.3 Manufacturing File Outputs Should have facility to publish to PDF, print or web with a controlled view of a project's history and dependencies, generate Gerber, Gerber X2, NC Drill, ODB++ 3D video animations, and STEP files. 1.4 Assembly file outputs Should generate assembly drawings, pick and place file, test point report. 1.5 Batch processing Should support post processing using Batch Process 1.6 System The software shall work in 64bit Windows 7 , Requirements Windows 8 or Windows 10 version desktop / laptop. Linux support is desirable but not essential. The software should work on intranet from behind proxy server of the organization and internet connectivity should not be essential for its installation, use and upgrade. 2 Library 2.1 Library Management Should have unified library management based on a single data source for all component models and linked data including 3D models, data sheets and supplier links. 2.2 Library Should have library of major components from reputed manufacturers with provision to download files and work offline. -

Elektronikentwicklung Unter Linux

Elektronikentwicklung unter Linux Clifford Wolf Clifford Wolf, 26. September 2010 http://www.clifford.at/ - p. 1 Einführung ● Behandelte Themen ● Unvollständigkeit Schaltungssimulation Leiterplattenentwurf und Schematic Einführung Compiler und Libraries Mathematik Mechanik Clifford Wolf, 26. September 2010 http://www.clifford.at/ - p. 2 Behandelte Themen Einführung ■ Schaltungssimulation ● Behandelte Themen ● Unvollständigkeit Schaltungssimulation ■ Leiterplattenentwurf und Schematic Leiterplattenentwurf und Schematic Compiler und Libraries ■ Compiler fuer embedded CPUs und ausgewaehlte Libraries Mathematik Mechanik ■ Mathematik ■ Mechanik Clifford Wolf, 26. September 2010 http://www.clifford.at/ - p. 3 Unvollständigkeit Einführung ■ Ich kann nur etwas über die Tools erzaehlen die ich selbst ● Behandelte Themen ● Unvollständigkeit verwende. Schaltungssimulation Leiterplattenentwurf und ■ Schematic Für Hinweise und Ergänzungen bin ich jederzeit offen und Compiler und Libraries dankbar. Mathematik Mechanik Clifford Wolf, 26. September 2010 http://www.clifford.at/ - p. 4 Einführung Schaltungssimulation ● QUCS ● GnuCap ● LTspice ● Java Circuit Simulator ● Icarus Verilog ● GTKWave Schaltungssimulation Leiterplattenentwurf und Schematic Compiler und Libraries Mathematik Mechanik Clifford Wolf, 26. September 2010 http://www.clifford.at/ - p. 5 QUCS Einführung http://qucs.sourceforge.net/ Schaltungssimulation ● QUCS ● GnuCap ■ Sehr sauber implementierter Simulator ● LTspice ● Java Circuit Simulator ● Icarus Verilog ● GTKWave ■ Gute GUI für Schematic-Entry -

Industrial Circuit Board Design and Microprocessor Programming Bachelor of Science Thesis in Mechatronics

Industrial circuit board design and microprocessor programming Bachelor of Science thesis in Mechatronics FREDRIK HÖGBERG Department of Signals and Systems CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Gothenburg, Sweden 2017 REPORT NO. XXXX XXXX Industrial circuit boar! design and %icroprocessor pro$ram%in$ FREDRIK HÖGBERG Depart%ent of Signal and S'ste%s CH)*MERS UNI,ERSIT- OF TE(HNO*OG- Gothenbur$, S/eden 2017 Industrial circuit board design and microprocessor pro$ra%%in$ FREDRIK HÖGBERG FREDRIK HÖGBERG, 2017 Technical report no xxxx544 Depart%ent of Signals and S'ste%s Chal%ers +ni6ersit' of Technolo$' SE-412 96 G;tebor$ S/eden Telephone + 46 (0)31-772 1000 (o6er5 Hot Screen 2000 is an industrial heat press machine that can be used to attach screen prints on clothin$. This thesis will go in to details on ho/ the circuit board and pro$ra% was ma!e for this %achine. Chal%ers Reproservice G;tebor$. S/eden 2017 CHALMERS Signals and Systems, Bachelor@s Thesis XXXX5XX I Abstract The %ain obAect of this proAect is to design and %aBe circuitr' to control a industrial heat press %achine. The circuitr' consist of a 0 la'er boar! containin$ a %icro controller. displa' %odule. )( DC module. te%perature controller and electronics to control electromechanical devices. The fra%e of reference /ill $o through the basics steps in designin$ and %anufacturin$ electrical circ"itry /ith digital and analo$ technolo$y and explain the basics of the most com%on electrical components use! in circuitr' toda'. The fra%e of reference /ill also sho/ ho/ to create sche%atic and circuit design "sin$ Ki()D and ho/ to pro$ra% a Microchi& %icroprocessor in the C pro$ra%ing lan$"a$e. -

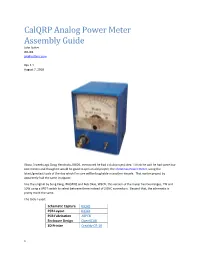

Calqrp Analog Power Meter Assembly Guide John Sutter W1JDS [email protected]

CalQRP Analog Power Meter Assembly Guide John Sutter W1JDS [email protected] Rev 1.1 August 7, 2018 About 3 weeks ago Doug Hendricks, KI6DS, mentioned he had a club project idea. I think he said he had some low cost meters and thought it would be good to spin an old project, the Christmas Power Meter, using the latest/greatest tools of the day which I’m sure will be laughable in another decade. That earlier project by apparently had the same instigator. Like the original by Song Kang, WA3AYQ and Bob Okas, W3CD, this version of the meter has two ranges, 1W and 10W using a SPDT switch to select between them instead of 2 BNC connectors. Beyond that, the schematic is pretty much the same. The tools I used: Schematic Capture KiCAD PCB Layout KiCAD PCB Fabrication AllPCB Enclosure Design OpenSCAD 3D Printer Creality CR-10 1 The Circuit As mentioned earlier the schematic matches the Christmas Power Meter pretty closely. SW1 is used to switch the power from the BNC connector into either the 10W load consisting of four 200 Ω 3 Watt carbon film resistors or the 1W load consisting of two 100 Ω ½ Watt carbon film resistors. The diodes are used as detectors with the resulting voltage filtered by the capacitors. The resistors are used to adjust the full-scale current to 200 μA. More on that later. FIGURE 1 SCHEMATIC A germanium diode was used on the 1 W range due to its lower voltage drop. More on that later. If you decide to use a through hole switch, the maximum shaft diameter is 6.3 mm.