A World Designed by God Science and Creationism in Contemporary Islam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Piyasa Meydan Muharebesi Kaç Gün Sürer?

Ve huzurlarınızda KETÖ! zun süredir fısıltı halinde duğu, ülkenin tren kazasıyla il- U dolaşan ve “Sıra onlara gili soru sorma ihtimallerinin da gelecek” listesinde yukarı- belirdiği bir zamanda. Moda larda olan kitleden biriydi Ad- tabirle, zamanlaması mani- nan Hoca ve Kedicikleri… Dün dar bir operasyondu yapılan. sürpriz bir operasyon ile Adnan Ki Cem Küçük gibi iktidar tetik- Hoca ve grubuna bağlı 235 kişi çilerinin “bir süre ortalıklarda gözaltına alındı. Tam da dola- görünme” talimatını yerine ge- rın fırladığı, borsanın dibe vur- tirmişti. NACI KARADAĞ’IN YORUMU 7’DE Sıcağa çarpılmayın! ARKA SAYFA’DA GÜNLÜK E-GAZETE — SAYI: 536 12 TEMMUZ 2018 PERŞEMBE WWW.TR724.COM — @TR724COM Unutulan sistem Catenaccio yeniden mi doğuyor! HASAN CÜCÜK’ÜN HABER YORUMU 14’TE Piyasa Meydan Muharebesi kaç gün sürer? ürkiye ekonomi cephesinde kriz- laşılmaya başlandı. Yasama, yürütme “Doları kimin yükselttiğini biliyoruz, T den çıkmak için son fırsatı 24 ve yargı artık Erdoğan’ın iki dudağı- hesabını verecekler.” ültimatomu ile Haziran 2018 Pazar günü heba etti. nın arasında. Erdoğan kararname muharebenin koordinatları hakkın- Aile şirketi gibi idare etme vekâletini ile devleti kendi tasavvur ettiği çiz- da hayli ipucu vermişti. Erdoğan ken- seçimde Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi giye çekiyor. AKP mahallesinde bile, disini başkomutan olarak görebilir. (AKP) lideri Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’a “Bu kadarı da ayıp. O kadar yetişmiş Amma velakin yatırımcı kurşun as- veren 26 milyon kişi (yüzde 52) irtifa insan varken Hazine’nin anahtarını ker ne de piyasa muharebe yapıla- kaybeden uçağın sert iniş yapmasını damada vermenin müdafaa edilecek cak bir meydanıdır. “İlle de çarpışaca- tercih etti. Piyasa Erdoğan’ın başkan bir tarafı yok.” sesleri yükseliyor. -

Franc-Maçonnerie, Sectes…Et Témoins De Jéhovah

Au nom de Allah le Tout Miséricordieux le Très Miséricordieux Franc-maçonnerie, Sectes…et Témoins de Jéhovah LIVRE 11 - Les Livres de Ribaat - 1er Édition 1433H / Septembre 2012 2ème Édition 1440H / Septembre 2018 SOMMAIRE ° Introduction. ° Les schismes engendrés du Diable. ° La Franc-maçonnerie mondiale. ° Les Charlatans sous couvert de piété. ° Le Mormonisme. ° Les Témoins de Jéhovah. ° Ahmed Deedat décrypte le mot « Jéhovah ». ° Débats religieux : Ribaat, les Mormons et Témoins de Jéhovah. ° Le Prophète Jésus (paix sur lui) n‟est pas une divinité IV. ° Les Livres 43 & 44. ° Conclusion. INTRODUCTION LIVRE 11 : FRANC-MAÇONNERIE, SECTES…ET TÉMOINS DE JÉHOVAH Ribaat Dans la Maison de l‟araignée surnommée « Nouvel ordre mondial », comploté durement par les chefs Jésuites/Juifs noachides au Vatican avec leurs plus serviles subordonnés, vous trouverez d‟autres sectes rapprochées à décrypter. Le bénéfice à en tirer n‟est pas de rentrer dans ces pièges d‟Iblis le djinn lapidé, mais de les désavouer et de vous éloigner d‟eux comme la peste pour votre Libération et Résistance Intellectuelle. Et dans le même temps, un retour à la prime nature dans le chemin droit de l‟adoration de votre propre Créateur Allah, le Dieu Unique. Tels sont les buts de la vie, avec une récompense et un châtiment éternel, au Jour de la Résurrection, au Jour des Comptes. Allah le Très Grand dit : « Dirige tout ton être vers la religion exclusivement [pour Allah], telle est la nature que Allah a originellement donnée aux hommes - pas de changement à la création de Allah -. Voilà la religion de droiture ; mais la plupart des gens ne savent pas. -

Evolution Education Around the Globe Evolution Education Around the Globe

Hasan Deniz · Lisa A. Borgerding Editors Evolution Education Around the Globe Evolution Education Around the Globe [email protected] Hasan Deniz • Lisa A. Borgerding Editors Evolution Education Around the Globe 123 [email protected] Editors Hasan Deniz Lisa A. Borgerding College of Education College of Education, Health, University of Nevada Las Vegas and Human Services Las Vegas, NV Kent State University USA Kent, OH USA ISBN 978-3-319-90938-7 ISBN 978-3-319-90939-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90939-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018940410 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

The Evolution Deceit

About The Author Now writing under the pen-name of HARUN YAHYA, Adnan Oktar was born in Ankara in 1956. Hav- ing completed his primary and secondary education in Ankara, he studied arts at Istanbul's Mimar Sinan Univer- sity and philosophy at Istanbul University. Since the 1980s, he has published many books on political, scientific, and faith-related issues. Harun Yahya is well-known as the author of important works disclosing the imposture of evo- lutionists, their invalid claims, and the dark liaisons between Darwinism and such bloody ideologies as fascism and com- munism. Harun Yahya's works, translated into 63 different lan- guages, constitute a collection for a total of more than 45,000 pages with 30,000 illustrations. His pen-name is a composite of the names Harun (Aaron) and Yahya (John), in memory of the two esteemed Prophets who fought against their peoples' lack of faith. The Prophet's seal on his books' covers is symbolic and is linked to their con- tents. It represents the Qur'an (the Final Scripture) and the Prophet Muhammad (saas), last of the prophets. Under the guid- ance of the Qur'an and the Sunnah (teachings of the Prophet [saas]), the author makes it his purpose to disprove each funda- mental tenet of irreligious ideologies and to have the "last word," so as to completely silence the objections raised against religion. He uses the seal of the final Prophet (saas), who attained ultimate wisdom and moral perfection, as a sign of his intention to offer the last word. All of Harun Yahya's works share one single goal: to convey the Qur'an's message, encour- age readers to consider basic faith-related is- sues such as Allah's existence and unity and the Hereafter; and to expose irreligious sys- tems' feeble foundations and perverted ide- ologies. -

1 Une Puissante Attraction Chez Les Islamistes Pour Les Contrevérités

Préjugés et convictions intolérantes de musulmans très convaincus (Anciennement : Le Bêtisier islamiste) Par Benjamin LISAN, Le 11/01/2018 « Le doute est à la base du raisonnement scientifique, et une assertion sur laquelle on n’a pas le droit d’émettre un doute ne peut pas être vérifiée et donc n’a aucune valeur scientifique ». 1 Une puissante attraction chez les islamistes pour les contrevérités Les islamistes ont une forte appétence pour les contre-vérité ou thèses (ou « bêtises ») pseudoscientifiques, complotistes … Quand ils ont le choix, ils préfèrent presque toujours choisir une « bêtise », même si elle est grosse comme une montagne, ou un thème étroit d’esprit, que de se dédire. La vérité scientifique n’a aucune espèce d’importance pour eux. Ce qui compte pour eux est que telle « vérité » prouve la « véracité » de l’islam et qu’elle sont compatible / conforme à l’islam. Et aussi de ne pas perdre la face, d’où un enlisement dans l’erreur, les contre-vérités et le mensonge. Si leur « bêtise » est réfutée par leur interlocuteur, ils ne se démontent jamais et rebondissent immédiatement en affirmant une nouvelle « bêtise » (pseudoscientifique, complotiste, délirante …). Dans ce bêtisiers, j’y ai consigné toutes leurs déclarations, caractérisées par des contre-vérités scientifiques ou leur sectarisme (intolérance). Dans ce document, dénommé « bêtisier », ci-après, j’ai classé les « bêtises » entre : 1) « Bêtises » pseudoscientifiques et raisonnement délirants (voire des superstitions), 2) Discours antisémites ou antimaçonniques, 3) Discours homophobe et transphobe, 4) Discours de haine anti-athées. 5) Discours suprémacistes, 6) Versets coraniques et hadiths contredisant les données scientifiques actuelles ou superstitieux, 7) Prises de position religieuses très partisanes ou fanatiques. -

The Mahdi Wears Armani

The Mahdi wears Armani wears Mahdi The The prolific Turkish author Harun Yahya attracted international attention after thousands of unsolicited copies of his large-format and lavishly illustrated book Atlas of Creation were sent free of charge from Istanbul, Turkey, to schools, universities and state leaders worldwide in 2007. This book stunt drew attention to Islamic creationism as a growing phenomenon, and to Harun Yahya as its most prominent proponent globally. Harun Yahya is allegedly the pen name of the Turkish author and preacher Adnan Oktar. Behind the brand name “Harun Yahya”, a highly prosperous religious enterprise is in operation, devoted not merely to the debunking of Darwinism, but THE also to the promotion of Islam. Backed by his supporters, Oktar channels vast financial resources into producing numerous books, dvds, websites and lately also television shows promoting his message. MAHDI The aim of this dissertation is to shed light on the Harun Yahya enterprise by examining selected texts published in the framework of the enterprise. It describes, WEARS analyzes and contextualizes four key themes in the works of Harun Yahya, namely conspiracy theories, nationalism/neo-Ottomanism, creationism and apocalypticism/ Mahdism. The dissertation traces the development of the enterprise from a religious ArMANI community emerging in Turkey in the mid-1980s to a global da‘wa enterprise, and examines the way in which its discourse has changed over time. The dissertation’s point of departure is the notion that the Harun Yahya enterprise and the ideas it promotes must primarily be understood within the Turkish context from which it emerged. Drawing on analytical frameworks from social movement theory and rhetorical analysis as well as contemporary perspectives on Islamic da‘wa and activism, the study approaches Harun Yahya as a religious entrepreneur seeking market shares in the contemporary market for Islamic proselytism by adopting and adapting popular discourses both in the Turkish and global contexts. -

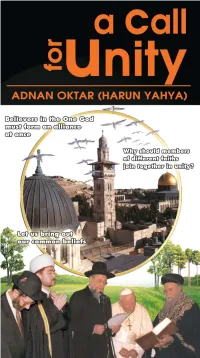

A CALL for UNITY and Placesthematourdisposalisgod

LIFE DID NOT COME INTO BEING BY CHANCE 2 SCIENTIFIC NONSENSE: THE THEORY OF EVOLUTION 4 THE PROOFS OF GOD’S EXISTENCE PERVADE THE ENTIRE UNIVERSE 6 DARWINISM IS A GRAVE THREAT TO COMMUNITIES 8 BELIEVERS IN THE ONE GOD MUST FORM AN ALLIANCE AT ONCE 10 WHY SHOULD MEMBERS OF DIFFERENT FAITHS JOIN TOGETHER IN UNITY? 14 THE THREAT OF RADICALISM: THE GOOD MUST UNITE AGAINST EVIL 15 LET US SPREAD THE FACT OF CREATION TOGETHER 16 A CALL TO BRING OUT OUR COMMON BELIEFS! 18 MUSLIMS ARE DEVOTED TO THE PROPHET JESUS (PBUH) WITH A VERY GREAT LOVE 20 HISTORY IS FULL OF EXAMPLES OF FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN MUSLIMS AND THE PEOPLE OF THE BOOK 22 THE SECOND COMING OF THE PROPHET JESUS (PBUH): GLAD TIDINGS COMMON TO CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS 24 THE SECOND COMING OF THE PROPHET JESUS (PBUH): GLAD TIDINGS COMMON TO CHRISTIAN WORLD 26 MUSLIMS WHO ABIDE BY THE QUR’AN ARE THE MOST MODERN PEOPLE IN THEIR ENVIRONMENTS 28 THE HEART IS ONLY SATISFIED WHEN IT TURNS TO GOD 30 A LAST WORD... 32 here can be no doubt that no- thing in the world is more impor- tant than a human being’s knowing our Creator. Knowing TGod, Who created us, is far more impor- tant and urgent than anything else in our lives. Let us consider the first of those things He has given us that come to mind... We live in a world specially created for life, planned down to the finest detail. But we did no- thing to establish that order. -

The Working Definition of Antisemitism – Six Years After

The Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities The Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary Anti-Semitism and Racism The Working Definition of Antisemitism – Six Years After Unedited Proceedings of the 10th Biennial TAU Stephen Roth Institute's Seminar on Antisemitism August 30 – September 2, 2010 Mémorial de la Shoah, Paris Contents Introduction The EUMC 2005 Working Definition of Antisemitism Opening Remarks: Simone Veil, Yves Repiquet Rifat Bali, "Antisemitism in Turkey: From Denial to Acknowledgement – From Acknowledgement to Discussions of Its Definition" Carole Nuriel, "History and Theoretical Aspects" Michael Whine, "Short History of the Definition" Ken Stern, "The Working Definition – A Reappraisal" David Matas, "Assessing Criticism of the EU Definition of Antisemitism" Dave Rich, "Reactions, Uses and Abuses of the EUMC Definition" Esther Webman, "Arab Reactions to Combating Antisemitism" Joel Kotek, "Pragmatic Antisemitism: Anti-Zionism as a New Civic Religion: The Belgium Case" Michal Navot, "Redux: Legal Aspects of Antisemitism, Holocaust Denial and Racism in Greece Today" Karl Pfeifer, "Antisemitic Activities of the Austrian 'Anti-Imperialists Coordination' (AIK)" Raphael Vago, "(Re)Defining the Jew: Antisemitism in Post-Communist Europe-the Balance of Two Decades" Marcis Skadmanis, "The Achievements of Latvian NGOs in Promoting Tolerance and Combating Intolerance" Yuri Tabak, "Antisemitic Manifestations in the Russian Federation 2009-2010" Irena Cantorovich, "Belarus as a Case Study of Contemporary Antisemitism" -

Sayin Adnan Oktar'in Ilmi Ve Fikri Faaliyetleri Ak Parti'nin Ideolojik Zemininin Oluşmasinda Çok Önemli Bir Vesile Olmuştur

SAYIN ADNAN OKTAR'IN İLMİ VE FİKRİ FAALİYETLERİ AK PARTİ'NİN İDEOLOJİK ZEMİNİNİN OLUŞMASINDA ÇOK ÖNEMLİ BİR VESİLE OLMUŞTUR İÇİNDEKİLER GİRİŞ BÖLÜM 1: SAYIN ADNAN OKTAR VE ARKADAŞLARININ TÜRKİYE’DE SAĞIN İKTİDARA GELEBİLMESİ İÇİN GEREKEN FELSEFİ VE İDEOLOJİK ALT YAPIYI SAĞLAMAK AMACIYLA YAPMIŞ OLDUKLARI SİYASİ FAALİYETLER 1.1. REFAH PARTİSİ’NE SEÇİMLER KAZANDIRAN MODERN VE YENİLİKÇİ GÖRÜNÜM 1.2. SAYIN ADNAN OKTAR’IN ARKADAŞLARI HEM SEÇİM SÜREÇLERİNE KATILARAK HEM DE PARTİ ÜYESİ OLARAK SAYIN ERBAKAN’A VE SAYIN ERDOĞAN’A ÇOK OLUMLU BİR TEVECCÜHÜN OLUŞMASINA VESİLE OLMUŞLARDIR 1.3. SAYIN ADNAN OKTAR’IN ARKADAŞLARI 1994 YEREL YÖNETİM SEÇİMLERİNDE SAYIN ERDOĞAN’IN YANINDA OLUP KENDİSİNİ DESTEKLEMİŞLERDİR 1.4. SAYIN ADNAN OKTAR’IN ARKADAŞLARININ REFAH PARTİSİ’NE VERDİĞİ DESTEK İLE İLGİLİ BASINDA ÇIKAN HABERLERDEN BİR KISMI 1.5. SAYIN ADNAN OKTAR’IN ARKADAŞLARINDAN SAYIN GÜLAY PINARBAŞI’NIN REFAH PARTİSİ’NE KATILIMIYLA İLGİLİ VERDİĞİ RÖPORTAJLARDAN BAZILARI 1.6. SAYIN ADNAN OKTAR’IN SAYIN ERBAKAN’A ve SAYIN ERDOĞAN’A DESTEĞİ İLE İLGİLİ YAPTIĞI AÇIKLAMALARDAN BAZILARI BÖLÜM 2: REFAH PARTİSİ İÇERİSİNDEKİ MODERNLİK KARŞITI ÇIKIŞLAR, 28 ŞUBAT POST-MODERN DARBESİ VE AK PARTİ'NİN KURULUŞU 2.1. AK PARTİ’NİN KURULUŞU VE SAYIN ERDOĞAN’IN MİLLİ GÖRÜŞ GÖMLEĞİNİ ÇIKARTTIM AÇIKLAMASI BÖLÜM3: SAYIN ADNAN OKTAR VE ARKADAŞLARININ TÜRKİYE’DE SAĞIN İKTİDARA GELEBİLMESİ İÇİN GEREKEN FELSEFİ VE İDEOLOJİK ALT YAPIYI SAĞLAMAK AMACIYLA YAPMIŞ OLDUKLARI FİKRİ FAALİYETLER 3.1. SAYIN ADNAN OKTAR’IN 1979’DAN GÜNÜMÜZE TÜRKİYE’DE SOLU VE KOMÜNİZMİ ÇÖKERTMESİ VE BÖYLELİKLE MODERN SAĞIN İNŞAASI 3.2. SAYIN ADNAN OKTAR VE ARKADAŞLARININ FİKRİ ÇALIŞMALARI AK PARTİ’NİN FELSEFİ ZEMİNİNİ OLUŞTURMUŞTUR 3.3. SAYIN DOĞU PERİNÇEK, “AK PARTİ’NİN FELSEFİ ZEMİNİNİ ADNAN OKTAR SAĞLADI” SÖZÜYLE AK PARTİ’NİN İKTİDARA GELİŞİNDE SAYIN ADNAN OKTAR’IN MUAZZAM ETKİSİNİ EN İYİ TAHLİL EDEN KİŞİLERDEN BİRİ OLMUŞTUR 3.4. -

The Theory of Evolution & Intelligent Design Around 1800

The Theory of Evolution & Intelligent Design Paul Schmid-Hempel ETH Zürich Institute for Integrative Biology (IBZ) around 1800: The Holy Script vs. nature • The Holy Script explains the origin of nature and of the organisms • These principles should be identical to what can be observed in nature (“nature is the creation of God”) • To detect the plan of the Creator: Carl von Linné, Isaac Newton,.... 1 Schrift: Genesis (1. Buch Mose) • “In the beginning God created animals and plants...” • ... • on day 3: plants... • on day 5: marine organisms and birds... • on day 6: animals on land, man • i.e. this is more or less simultaneously... Layers & Fossils 2 The book of nature young layers This is not simultaneous. Nature contradicts the Script. old layers The book of nature (1) Independent creation 1817: Baron Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) 1830/33: Charles Lyell (1797-1875) 3 The book of nature (1) Independent creation (2) Descent with modification 1837: Charles Darwin (1809-1882) 1858: Alfred Russell Wallace (1823-1913) Evolution of man 4 Evolution in the genus Homo Darwin: Descent and process 1. Individuals within a population differ in their characteristics (Variation) 2. These characteristics are partly heritable (Heritability) 3. There are more offspring born than can survive and reproduce (Fecundity) 4. Variants with suitable characteristics have higher chances to survive and reproduce (Selection) 5. These variants inevitably will become more frequent (Adaptation) 5 Genetic information: Transmission . Gregor Mendel (1823-1884) Laws of heredity (1860). Modular transmission (“genes”). August Weisman (1834-1914): Soma and germ line. Significance of selection. Hugo de Vries (1848-1935): Re-discovers Mendel’s laws around 1900. -

Turkey: Surveillance, Secrecy and Self-Censorship

SURVEILLANCE, SECRECY AND SELF-CENSORSHIP NEW DIGITAL FREEDOM CHALLENGES IN TURKEY Cover: Istanbul under surveillance. Credits to Boris Thaser. Editors: Sarah Clarke, Marian Botsford Fraser, Ann Harrison Research by Alev Yaman With thanks to: Daniel Bateyko, Alex Charles, Pepe Mercadal Baquero, Ariadna Martin Ribas, Marc Aguilar Soler and Jennifer Yang This publication is a joint report by PEN International and PEN Norway. PEN International promotes literature and freedom of expression and is governed by the PEN Charter and the principles it embodies: unhampered transmission ofthought within each nation and between all nations. Founded in 1921, PEN International connects an international community of writers from its Secretariat in London. It is a forum where writers meet freely to discuss their work; it is also a voice speaking out for writers silenced in their own countries. PEN International is a non-political organisation which holds Special Consultative Status at the UN and Associate Status at UNESCO. International PEN is a registered charity in England and Wales with registration number 1117088. www.pen-international.org Copyright © 2014 PEN International | PEN Norway All Rights Reserved PREFACE 2 TIMELINE 4 Turkey and Online Censorship INTRODUCTION AND 9 RECOMMENDATIONS TURKEY ONLINE 17 and the PEN Declaration on Digital Freedom CHAPTER 1 21 Restrictions on Individual’s Right to Freedom of Expression Online in Turkey CHAPTER 2 33 Online Censorship in Action CHAPTER 3 41 Surveillance and the use of Digital Evidence: The Erosion of Privacy in the Online Sphere CHAPTER 4 53 Online Service Providers and Freedom of Expression in Turkey CHAPTER 5 61 Conclusions and Recommendations ENDNOTES PREFACE The silenced voice of journalist Can Dündar is the preface of this report. -

Intelligent Design and the Assault on Science

Intelligent design and the assault on science Juli Peretó 13 July 2006 Creationism is enjoying a new lease of life. Sanctioned by the slogan "teach the controversy", the theory of intelligent design is gaining a foothold in educational establishments in the US and worldwide. Biochemist Juli Peretó delivers a rebuke to the fallacies and dishonesties of the theory of intelligent design and examines the ambiguous attitude of the Catholic Church towards creationism. Without evolutionary theory, contemporary biology would collapse entirely. Without the evolutionary framework, which is a coherent and fascinating vision of nature, in which cruelty and crudeness are transformed into a marvel of countless forms and behaviours, a glorious view of life connected with the cosmos, Earth, and the rest of the natural phenomena, would lose all its sense and elegance. The only new theory that present-day science could admit would be one that encompasses and perfects the Darwinian view of the natural world, as a step forward that would illuminate the many details of the origins of life that remain to be discovered or that resist our ability to understand the world. There is no way that substituting scientific scrutiny with obscurantism because of lack of data and observations, abandoning confidence in reason and recognising the failure of intelligence, can ever advance knowledge. Why should we accept that there is an impenetrable barrier to reason in the most intimate interstices of cellular structures and the most basic biochemical processes? Creationism, and its latest variant, the so-called “theory of intelligent design”, is inadmissible as an alternative explanation to the theory of evolution because it involves the surrender of reason.