Contractor Performance on Mega Projects – Avoiding the Pitfalls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aurora on Pirie

AURORA ON PIRIE soliD structural REPutation tructural Systems is one of Australia’s leading providers of specialist installation of post-tensioning. The components used by Structural CreatinG WHat Matters Sengineering, contracting and manufacturing services to the Systems on the project were specific to their particular process, which construction and mining sectors. Established in 1959 the company has consisted of high tensile strand, galvanised ducts, metal castings, ith over 80 years of experience within the Australian building Priorities for Baulderstone throughout the duration of the strata-title expanded to include offices throughout Australia, the Middle East and the anchor block and wedges and grout to fill the system after the concrete and infrastructure industry, Baulderstone were the design and project were safety, program and quality. Baulderstone completed the United Kingdom. is placed. construct contractor of choice for the Aurora on Pirie project in Adelaide. project with their trademark optimal safety record and the development practically completed defect free. An acknowledged leader in the post-tensioning field, Structural Systems Structural Systems’ industry-leading expertise in post-tensioning is For this multi-story office building, Baulderstone actioned a raft has a solid reputation for service, quality and innovation. Providing on-site currently being actioned on the Adelaide Desalination Project, World slab alternative for the construction which ultimately proved to be a Baulderstone’s body of work extends throughout Australia and includes; labour and materials, Structural Systems has assisted in building some of Park, 140 North Terrace and the Walkerville Town Centre. time-saving solution for the project. In conjunction with a specialised the Sydney Opera House, Melbourne Etihad Stadium, Sydney’s Anzac the world’s largest buildings, bridges and dams. -

Megabang for Megabucks: Driving a Harder Bargain on Megaprojects

Megabang for megabucks Driving a harder bargain on megaprojects Marion Terrill, Owain Emslie, and Lachlan Fox May 2021 Megabang for megabucks: Driving a harder bargain on megaprojects Grattan Institute Support Grattan Institute Report No. 2021-04, May 2021 Founding members Endowment Supporters This report was written by Marion Terrill, Owain Emslie, and Lachlan The Myer Foundation Fox. Nat Manawadu provided extensive research assistance and made National Australia Bank substantial contributions. Susan McKinnon Foundation We would like to thank numerous government and industry participants Affiliate Partners and officials for their helpful comments and insights. Ecstra Foundation The opinions in this report are those of the authors and do not Origin Energy Foundation necessarily represent the views of Grattan Institute’s founding Susan McKinnon Foundation members, affiliates, individual board members, reference group members, or reviewers. The authors are responsible for any errors or Senior Affiliates omissions. Cuffe Family Foundation Grattan Institute is an independent think tank focused on Australian Maddocks public policy. Our work is independent, practical, and rigorous. We aim Medibank Private to improve policy by engaging with decision makers and the broader The Myer Foundation community. Scanlon Foundation We acknowledge and celebrate the First Nations people on whose Trawalla Foundation traditional lands we meet and work, and whose cultures are among the Wesfarmers oldest continuous cultures in human history. Westpac For further information on Grattan’s programs, or to join our mailing list, Affiliates please go to: www.grattan.edu.au. You can make a donation to support Allens future Grattan reports here: www.grattan.edu.au/donate. Ashurst This report may be cited as: Terrill, M., Emslie, O., and Fox, L. -

Lend Lease - Springfield Lakes South West Brisbane

Lend Lease - Springfield Lakes South West Brisbane Information Memorandum Contents 1. About Lend Lease .................................................................................................................................. 3 1.1 Springfield Lakes Residential Community ..................................................................................... 6 1.2 Springfield Lakes from the air ....................................................................................................... 8 2. Introduction to Springfield Lakes .......................................................................................................... 9 3. The Location .......................................................................................................................................... 9 4. Local Growth Drivers ........................................................................................................................... 10 4.1 Education .................................................................................................................................... 10 4.2 Transport ..................................................................................................................................... 11 4.3 Shopping and Lifestyle ................................................................................................................ 11 4.4 Sports and outdoor Lifestyle ....................................................................................................... 12 4.5 Queensland’s -

Inner Brisbane Heritage Walk/Drive Booklet

Engineering Heritage Inner Brisbane A Walk / Drive Tour Engineers Australia Queensland Division National Library of Australia Cataloguing- in-Publication entry Title: Engineering heritage inner Brisbane: a walk / drive tour / Engineering Heritage Queensland. Edition: Revised second edition. ISBN: 9780646561684 (paperback) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Brisbane (Qld.)--Guidebooks. Brisbane (Qld.)--Buildings, structures, etc.--Guidebooks. Brisbane (Qld.)--History. Other Creators/Contributors: Engineers Australia. Queensland Division. Dewey Number: 919.43104 Revised and reprinted 2015 Chelmer Office Services 5/10 Central Avenue Graceville Q 4075 Disclaimer: The information in this publication has been created with all due care, however no warranty is given that this publication is free from error or omission or that the information is the most up-to-date available. In addition, the publication contains references and links to other publications and web sites over which Engineers Australia has no responsibility or control. You should rely on your own enquiries as to the correctness of the contents of the publication or of any of the references and links. Accordingly Engineers Australia and its servants and agents expressly disclaim liability for any act done or omission made on the information contained in the publication and any consequences of any such act or omission. Acknowledgements Engineers Australia, Queensland Division acknowledged the input to the first edition of this publication in 2001 by historical archaeologist Kay Brown for research and text development, historian Heather Harper of the Brisbane City Council Heritage Unit for patience and assistance particularly with the map, the Brisbane City Council for its generous local history grant and for access to and use of its BIMAP facility, the Queensland Maritime Museum Association, the Queensland Museum and the John Oxley Library for permission to reproduce the photographs, and to the late Robin Black and Robyn Black for loan of the pen and ink drawing of the coal wharf. -

LEND LEASE APPROACH Our Approach to Sustainability Supports Our Aim to Be the Leading International Property and Infrastructure Group

SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2011 MESSAGE FROM STEVE MCCANN Welcome to Lend Lease’s 2011 Sustainability Report. Sustainability is part of how we do business at Lend Lease. Every day we consider the environmental, social, ethical and financial impacts of what we do. Safety first Operating Incident & Injury Free is the most important challenge we face, and it is essential to the ongoing success of our operations. Our Asia, EMEA and Americas businesses reported no fatalities in the 2011 financial year, however we deeply regret that one person lost his life in our Australian operations. Over the past five years, our efforts to make safety the responsibility of every individual, not only the safety teams, have resulted in improved incident frequency rates and an 80 per cent reduction in our fall of person incidents. This year, we focused on safety leadership, improving our operating disciplines and driving appropriate behaviours to embed a positive safety culture. We will continue to prioritise safety and drive uncompromising leadership through our businesses. Caring for our environment We are constantly identifying, understanding and mitigating the environmental impacts of our projects. This year we continued to invest in clean technologies, expanded our green building practices and helped lead the industry through partnerships and advocacy to generate environmental change. We are proud to be one of fourteen organisations partnering with the United States administration, under President Obama, to increase energy efficiency under the Better Buildings Challenge. In the past year, we implemented an integrated Environmental, Health and Safety (EH&S) Management System that provides us with a company-wide global framework to identify risk, manage the impact of our activities, and continuously improve our performance. -

Lend Lease Securityholder Review 2011

LEND LEASE SECURITYHOLDER REVIEW 2011 QUICK FACTS & HIGHLIGHTS Lend Lease achieved earnings growth across all regions and continued to build a strong development pipeline n New infrastructure business in Australia following acquisition of Abigroup, Baulderstone and Conneq n Over 17,000 employees, an increase of over 6,000 employees from the 2010 financial year n Funds under management of $10.9 billion n Credit rating (Standard & Poor’s/Moody’s) of BBB-/Baa3 (stable) Asia Americas Asia Americas Asia Americas 50% 31% 9%EMEA Australia EMEA Australia EMEA Australia increase increase increaseInfrastructure Millions of hours worked Infrastructure Millions of hours worked Infrastructure Millions of hours worked 500 10120 250 1080 250 10 250 Operating 460 1139 225 729 225 9 225 Profit after .0 .0 420 77 10677 8 200 648 200 8 200 485.3 1.4 7 8. Tax ($ million) 11 380 997 175 567 175 7 175 445.9 10 435.9 Earnings per Distribution per $161.7m 340 Security (cents) 926 Security (cents)150 486 150 6 150 300 855 125 405 125 5 125 260 784 100 324 100 4 100 323.6 20.5c 2.9c .4 85.6 1 0 41.0 1 67 291.7 220 713 75 243 75 3 75 65. 35. 32. 180 642 50 162 50 2 50 140 571 25 18 25 1 25 07 08 09 10 07 08 09 10 07 08 09 10 11 11 11 100 500 07 08 09 10 11 0 00 07 08 09 10 11 0 0 07 08 09 10 11 0 n Profit growth in all regions n The Group achieved milestones n 41 perNotes cent of Operating Profit Notes Notes contributed to an increase in on major projects and after• TaxAustralian was financial distributed year (July - June )to • Australian financial year (July - June) • Australian financial year (July - June) Operating Profit after Tax of recycled assets. -

Exelarm Security & Communications

Exelarm Security & Communications Here follows a cross-section of Exelarm Construction Industry clients. We invite you, without reservation, to contact them should you wish to do so. Abigroup Nursecall/Security/Paging/Evacuation Adco Construction Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Alimack Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation All State Electrical Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation AJS Electrical Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Austin Construction Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Austin Arenco Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Australand Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation BBS Construction Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Banabelle Electrics Security/Nursecall Barclay Mowlem Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Barnwell Cambridge Electrical Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Battison Electrical Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Belmorgan Property Development Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Baulderstone Hornibrook Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Buildcorp Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Built Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Buildform Australia Pty Ltd Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Bovis Lendlease Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Byrne Lewis Construction Security/Nursecall CCH Security/Nursecall CCL NSW [Now Walters] Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation CCL ACT [Now Walters] Security/Nursecall CCL Melbourne [Now Walters] Security/Nursecall City Electrical Services Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Civil & Civic [Now Bovis Lendlease] Security/Nursecall/Paging/Evacuation Construction -

Second Further Amended Statement of Claim Filed

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA (FCA) NEW SOUTH WALES REGISTRY - FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA GENERAL DIVISION No: NSD757/2012 NOTICE OF FILING This document was filed electronically in the FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA (FCA) on 31/03/2014. DETAILS OF FILING Document Lodged: Amended Document File Number: NSD757/2012 File Title: Stephen Hopkins and another named in the Schedule as Trustees for the Hopkins Superannuation Fund v AECOM Australia Pty Ltd ACN 093 846 925 (formerly known as Maunsell Australia Pty Ltd) District Registry: NEW SOUTH WALES REGISTRY - FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA Dated: 1/04/2014 Registrar Note This Notice forms part of the document and contains information that might otherwise appear elsewhere in the document. The Notice must be included in the document served on each party to the proceeding. Form 17 Rule 8.05(1)(a) Second further amended statement of claim (Filed with leave of Nicholas J granted on 13 March 2014) No 757 of 2012 Federal Court of Australia District Registry: New South Wales Division: General Stephen Hopkins and another as Trustees for The Hopkins Superannuation Fund Applicants AECOM Australia Pty Ltd (ACN 093 846 925) (formerly known as Maunsell Australia Pty Ltd) First Respondent RiverCity Motorway Management Limited (Administrators appointed) ACN 117 343 361 Second Respondent RiverCity Motorway Services Pty Ltd (Administrators appointed) (Receivers and Managers appointed) ACN 117 139 992 Third Respondent And others named in the Schedule Preliminary 1. This proceeding is commenced as a representative -

ASX Announcement

ASX Announcement Results for Announcement to the Market Preliminary Final Report – Listing Rule 4.3A 30 August 2012 Lend Lease Group today announces its results for the year ended 30 June 2012. Attached are the following documents: Preliminary Final Report (Appendix 4E) Full Year Consolidated Financial Report Management Discussion & Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations Portfolio Report Five Year Profile Directors’ Report Consolidated Financial Statements Independent Auditor’s Report For further information, please contact: Investor Relations: Corporate Affairs: Sally Cameron Iwona Polski Group Executive - Investor Relations Media & External Communications Manager Tel:02 9236 6464 Tel: 02 9237 5034 Lend Lease Corporation Limited ABN 32 000 226 228 1 and Lend Lease Responsible Entity Limited ABN 72 122 883 185 AFS Licence 308983 as responsible entity for Lend Lease Trust ABN 39 944 184 773 ARSN 128 052 595 Level 4, 30 The Bond Telephone +61 2 9236 6111 30 Hickson Road Facsimile +61 2 9252 2192 Millers Point NSW 2000 www.lendlease.com Australia Lend Lease Group Appendix 4E Lend Lease Group (‘the Group’) comprises Lend Lease Corporation Limited (‘the Company’) ABN 32 000 226 228 and Lend Lease Trust (‘LLT’) ARSN 128 052 595 the responsible entity of which is Lend Lease Responsible Entity Limited ABN 72 122 883 185 Preliminary Final Report for the financial year ended 30 June 2012 (previous corresponding period being the financial year ended 30 June 2011) Results for Announcement to the Market Profit After Tax June 2012 June 2011 % A$m A$m Change Revenue 11,547.5 8,926.7 29.4 Profit after tax attributable to securityholders 501.4 492.8 1.7 Stapling of the Company Shares and LLT Units Shares in the Company and units in LLT are traded as one security under the name of Lend Lease Group on the Australian Securities Exchange (‘ASX’). -

Kurilpa Bridge

KURILPA BRIDGE BAULDERSTONE BRISBANE QLD verything about Brisbane’s Kurilpa Bridge is a finely tuned balancing To achieve this extraordinary civic infrastructure feat took 25 In addition, feeder barges were utilised to deliver supplies including A Voluntary Impact Statement was carried out before works commenced, act, from the tensegrity structure itself to the construction process, Baulderstone Queensland staff, and fifty separate subcontractors and structural steel and precast concrete elements, steel reinforcement which resulted in mitigation plans for marine impacts, such as silt booms managed by Baulderstone Queensland. suppliers ranging from crane companies to barges. Project Manager Paul and cables. around key working areas in the river. Stathis estimated 1,100 individual site inductions were carried out, and A world-first in design and engineering terms, the bridge combines tension that at any one time there were 65 people active on-site. “There were a The design of piers and marine piling had to be made strong enough Baulderstone has previous experience on other Brisbane River Bridge and compression elements in such a way some of the main supports lot of specialists involved,” he said. to withstand the impact of a barges sent out of control by a major icons, namely the William Jolly Bridge, the Victoria Road Bridge and appear to be floating. An estimated 550 tonnes of structural steel, including flood event. the Story Bridge. Other major projects currently being completed approximately 6.8 kilometres of spiral strand cable are incorporated into Construction commenced with site establishment in October 2007, with by Baulderstone include the Gibson Island Water Treatment Plant, the pedestrian and cycleway which spans the Brisbane River between the completion due September 2009. -

ROBERT BILECKIJ PARTNER Sydney Australia

ROBERT BILECKIJ PARTNER Sydney Australia Robert is a partner in our Corporate and Funds Practice. +61 2 9322 4390 +61 418 388 629 [email protected] BACKGROUND Robert holds both a Bachelor of Laws and a Bachelor of Business degree and is admitted to practice in NSW. His experience in the property and financial services industries include periods of secondment to Lendlease (as acting General Counsel) and MLC. Robert is also a member of the Property Council of Australia’s Corporate Finance Working Group. KEY SERVICES KEY SECTORS Real Estate Funds Real Estate Mergers & Acquisitions Banks and other Financial Institutions EXPERIENCE Robert advises on corporate transactions, fund raisings, funds management, mergers and acquisitions and joint ventures. His practice spans a number of sectors including real estate, infrastructure and financial services, with a focus on the property funds management industry. Robert has acted extensively on establishing, investing into and transacting with a broad range of funds structures and assets, through which he has gained a deep knowledge of key drivers and market settings. Recent experience includes: restructure (via a series of trust schemes) and listing of the Aventus Retail Property Fund establishing the investment vehicles for the A$6 billion Barangaroo development in Sydney acting for Lendlease on establishing a joint venture with Ping An and Mitsubishi for the A$1.5 billion Circular Quay Towers project acting for Lendlease on its A$1.06 billion acquisition of Valemus (Abigroup and Baulderstone) acting for Wesfarmers on the sale of its underwriting business to IAG acting for NAB on its A$825 million acquisition of the Aviva Australia life insurance and wealth management platform © HERBERT SMITH FREEHILLS LLP 2021. -

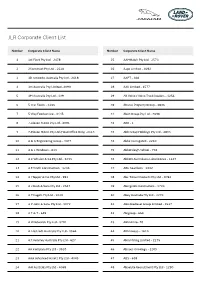

JLR Corporate Client List

JLR Corporate Client List Number Corporate Client Name Number Corporate Client Name 1 1st Fleet Pty Ltd - 2478 25 AAMHatch Pty Ltd - 2573 2 2Construct Pty Ltd - 2620 26 Aapc Limited - 4092 3 3D networks Australia Pty Ltd - 2618 27 AAPT - 468 4 3m Australia Pty Limited -4090 28 AAV Limited - 1577 5 3M Australia Pty Ltd - 139 29 AB Volvo / Volvo Truck Dealers - 1256 6 5 Star Foods - 3166 30 Abacus Property Group - 3036 7 5 Way Foodservice - 3145 31 Abah Group Pty Ltd - 2698 8 7-eleven Stores Pty Ltd - 4091 32 ABB - 1 9 7-Eleven Stores Pty Ltd (Head Office Only) -2113 33 Abb Group Holdings Pty Ltd - 4093 10 A & G Engineering Group - 3473 34 Abbe Corrugated - 2210 11 A & L Windows - 613 35 Abbotsleigh School - 702 12 A C Whalan & Co Pty Ltd - 3233 36 Abbott Australasia Laboratories - 1247 13 A E Smith Construction - 1236 37 ABC Seamless - 1002 14 A I Topper & Co. Pty Ltd - 991 38 Abc Tissue Products Pty Ltd - 4094 15 A J Bush & Sons Pty Ltd - 2647 39 Abergeldie Contractors - 1724 16 A P Eagers Pty Ltd - 3020 40 Abey Australia Pty Ltd - 3270 17 A P John & Sons Pty Ltd - 1072 41 ABG Biodiesel Group Limited - 1537 18 A T & T - 649 42 Abigroup - 650 19 A W Edwards Pty Ltd - 3701 43 ABN Amro -70 20 A. Hartrodt Australia Pty Ltd - 3564 44 ABN Group - 1610 21 A.T. Kearney Australia Pty Ltd - 627 45 Abra Mining Limited - 2275 22 AA Company Pty Ltd - 3510 46 Abraxis Oncology - 2209 23 AAA Advanced Assets Pty Ltd - 4045 47 ABS - 638 24 AAI Australia Pty Ltd - 4068 48 Absolute Recruitment Pty Ltd - 1290 JLR Corporate Client List Number Corporate Client