2018 Two Houses.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Digital Movies As Malaysian National Cinema A

Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Hsin-ning Chang April 2017 © 2017 Hsin-ning Chang. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema by HSIN-NING CHANG has been approved for Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Erin Schlumpf Visiting Assistant Professor of Film Studies Elizabeth Sayrs Interim Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT CHANG, HSIN-NING, Ph.D., April 2017, Interdisciplinary Arts Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema Director of dissertation: Erin Schlumpf This dissertation argues that the alternative digital movies that emerged in the early 21st century Malaysia have become a part of the Malaysian national cinema. This group of movies includes independent feature-length films, documentaries, short and experimental films and videos. They closely engage with the unique conditions of Malaysia’s economic development, ethnic relationships, and cultural practices, which together comprise significant understandings of the nationhood of Malaysia. The analyses and discussions of the content and practices of these films allow us not only to recognize the economic, social, and historical circumstances of Malaysia, but we also find how these movies reread and rework the existed imagination of the nation, and then actively contribute in configuring the collective entity of Malaysia. 4 DEDICATION To parents, family, friends, and cats in my life 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Prof. -

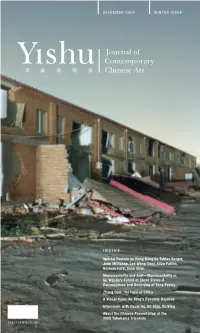

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE Special Feature on Hong Kong By

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE INSIDE Special Feature on Hong Kong by Tobias Berger, John Millichap, Lee Weng Choy, Eliza Patten, Norman Ford, Sean Chen Monumentality and Anti—Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles-A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Zhang Dali: The Face of China A Visual Koan: Xu Bing's Dynamic Desktop Interviews with Oscar Ho, Uli Sigg, Xu Bing About the Chinese Presentation at the 2005 Yokohama Triennale US$12.00 NT$350.00 US$10.00 NT$350.00 Art & Collection Editor’s Note Contributors Hong Kong SAR: Special Art Region Tobias Berger p. 16 The Problem with Politics: An Interview with Oscar Ho John Millichap Tomorrow’s Local Library: The Asia Art Archive in Context Lee Weng Choy 24 Report on “Re: Wanchai—Hong Kong International Artists’ Workshop” Eliza Patten Do “(Hong Kong) Chinese” Artists Dream of Electric Sheep? p. 29 Norman Ford When Art Clashes in the Public Sphere— Pan Xing Lei’s Strike of Freedom Knocking on the Door of Democracy in Hong Kong Shieh-wen Chen Monumentality and Anti-Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles—A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Wu Hung From Glittering “Stars” to Shining El Dorado, or, the p. 54 “adequate attitude of art would be that with closed eyes and clenched teeth” Martina Köppel-Yang Zhang Dali: The Face of China Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky Collecting Elsewhere: An Interview with Uli Sigg Biljana Ciric A Dialogue on Contemporary Chinese Art: The One-Day Workshop “Meaning, Image, and Word” Tsao Hsingyuan p. -

Performance Art

(hard cover) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Master of Arts Fine Arts 2006 LASALLE-SIA COLLEGE OF THE ARTS (blank page) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts) LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts Faculty of Fine Arts Singapore May, 2006 ii Accepted by the Faculty of Fine Arts, LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts). Vincent Leow Studio Supervisor Adeline Kueh Thesis Supervisor I certify that the thesis being submitted for examination is my own account of my own research, which has been conducted ethically. The data and the results presented are the genuine data and results actually obtained by me during the conduct of the research. Where I have drawn on the work, ideas and results of others this has been appropriately acknowledged in the thesis. The greater portion of the work described in the thesis has been undertaken subsequently to my registration for the degree for which I am submitting this document. Lee Wen In submitting this thesis to LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations and policies of the college. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the work may be made available and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. This work is also subject to the college policy on intellectual property. -

SORS-2021-1.2.Pdf

Office of Fellowships and Internships Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC The Smithsonian Opportunities for Research and Study Guide Can be Found Online at http://www.smithsonianofi.com/sors-introduction/ Version 1.1 (Updated August 2020) Copyright © 2021 by Smithsonian Institution Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 How to Use This Book .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Anacostia Community Museum (ACM) ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Archives of American Art (AAA) ....................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Asian Pacific American Center (APAC) .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage (CFCH) ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum (CHNDM) ............................................................................................................................. -

The Self-Organization of Contemporary Art in China, 2001–2012

Bao Dong Rethinking Practices within the Art System: The Self-Organization of Contemporary Art in China, 2001–2012 The Origin of the Term “Self-Organization” in China The term “self-organization” was first used in the context of contemporary Chinese art in 2005 at the Second Guangzhou Triennial curated by Hou Hanru, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and Guo Xiaoyan. Self-organization was one of the special projects of the triennial, and there were two panel discussions on the topic. The exhibition theme “Beyond” focused on the topic of alternative modernity in China and non-Western countries, and the term self-organization was defined by the following statements: “A number of independent art organizations, institutions, and communities have taken an active role in artistic creation and practice” and “their projects are often diverse, flexible” and “self-induced in nature.”1 Altogether, twenty-four self- organized groups2 were included in this project, and for the curators, the concept of “self-organization” was used to differentiate independent and autonomous organizations from those attached to government systems or political parties. This feature is also the fundamental difference between the various artist-run autonomous organizations and the organizations within the conventional art system as constituted by Chinese Artists Association, along with the various academies of painting, art institutes, museums, and so on. In other words, self-organization is considered a force operating outside of the conventional art system, just as the inception, growth, and flourishing of contemporary Chinese art is believed to have been achieved outside of official systems. In terms of any independence from the conventional art system, self- organization is not a new phenomenon in the contemporary Chinese art scene. -

Bingfeng, Dong. "Cinema of Exhibition: Film in Chinese Contemporary Art

Bingfeng, Dong. "Cinema of Exhibition: Film in Chinese Contemporary Art: In conversation with Tianqi Yu Translated by Hui Miao." China’s iGeneration: Cinema and Moving Image Culture for the Twenty-First Century. Ed. Matthew D. Johnson, Keith B. Wagner, Tianqi Yu and Luke Vulpiani. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 73–86. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501300103.ch-004>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 10:59 UTC. Copyright © Matthew D. Johnson, Keith B. Wagner, Tianqi Yu, Luke Vulpiani and Contributors 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 4 Cinema of Exhibition: Film in Chinese Contemporary Art Dong Bingfeng In conversation with Tianqi Yu Translated by Hui Miao Dong Bingfeng is regarded as one of the most active curators and art critics working on Chinese contemporary art and visual culture in mainland China today. In the past eight years he has worked at several different contemporary art museums, including the Guangdong Art Museum, Ullens Center for Contemporary Art and Iberia Center for Contemporary Art. At these leading art institutions, he explored the nature and ontology of the ‘moving image’ in its various forms – video art, new media art, video and film installations – pushing the boundaries of the various forms and decon- structing the moving image culture. Currently, Dong is the artistic director at the Li Xianting Film Fund, where he has implemented an intensive exploration into artists’ films shown in gallery spaces, or what has been recently referred to as ‘cinema of exhibition.’ China’s iGeneration co-editor Tianqi Yu interviewed Dong Bingfeng on the emerging field of ‘cinema of exhibition,’ and in the interview Dong shares some of his views on cinema and moving image culture, particularly among China’s current iGeneration. -

Malaysia's Security Practice in Relation to Conflicts in Southern

LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE Malaysia’s Security Practice in Relation to Conflicts in Southern Thailand, Aceh and the Moro Region: The Ethnic Dimension Jafri Abdul Jalil A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations 2008 UMI Number: U615917 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615917 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Libra British U to 'v o> F-o in andEconor- I I ^ C - 5 3 AUTHOR DECLARATION I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Jafri Abdul Jalil The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted provided that full acknowledgment is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without prior consent of the author. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. -

Big Business, Selling Shrimps: the Market As Imaginary in Post-Mao

For decades critics have written disapprovingly about the relationship between the market and art. In the 1970s proponents of institutional critique wrote in Artforum about the degrading effects of money on art, and in the 1980s Robert Hughes (author of Shock of the New and director of The Mona Lisa Curse) compared the 01/07 deleterious effect of the market on art to that of strip-mining on nature.1ÊMore recently, Hal Foster has disparaged the work of some of the markets hottest art stars – Takashi Murakami, Damien Hirst, and Jeff Koons – declaring that their pop concoctions lack tension, critical distance, and irony, offering little more than “giddy delight, weary despair, or a manic- Jane DeBevoise depressive cocktail of the two.”2 And Walter Robinson has spoken about the ability of the market to act as a kind of necromancer, Big Business, reanimating mid-century styles of abstract painting for the purposes of flipping canvas like Selling real estate – a phenomenon he calls “zombie formalism.”3 Shrimps: The ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊMoralistic attacks against the degrading impact of the market on art are not unique to US- based critics. Soon after the end of the Cultural Market as Revolution, when few people think China had any art market at all, plainly worded attacks on Imaginary in commercialism appeared regularly in the nationally circulated art press. As early as 1979, a n i Jiang Feng, the chair of the Chinese Artists h Post-Mao China C Association, worried in writing that ink painters o a were churning out inferior works in pursuit of M - t 4 s material gain.Ê ÊIn 1983, the conservative critic o P Hai Yuan wrote that “owing to the opportunity for n i y high profit margins, many painters working in oil r a n or other mediums have switched to ink painting.” i g e a s And, what was worse, to maximize their gain, i m o I v these artists “sought to boost their productivity s e a B 5 t e by acting like walking photocopy machines.” In e D k e r the 1990s supporters of experimental oil a n a M painting also came under fire. -

Exhibition Guide

ArTScience MuSeuM™ PreSenTS ceLeBrATinG SinGAPOre’S cOnTeMPOrArY ArT Exhibition GuidE Detail, And We Were Like Those Who Dreamed, Donna Ong Open 10am to 7pm daily | www.MarinaBaySands.com/ArtScienceMuseum Facebook.com/ArtScienceMuseum | Twitter.com/ArtSciMuseum WELCOME TO PRUDENTIAL SINGAPORE EYE Angela Chong Angela chong is an installation artist who Prudential Singapore Eye presents a with great conceptual confidence. uses light, sound, narrative and interactive comprehensive survey of Singapore’s Works range across media including media to blur the line between fiction and contemporary art scene through the painting, installation and photography. reality. She has shown work in Amsterdam Light Festival in the netherlands; Vivid works of some of the country’s most The line-up includes a number of Festival in Sydney; 100 Points of Light Festival innovative artists. The exhibiting artists who are gaining an international in Melbourne; cP international Biennale in artists were chosen from over 110 following, to artists who are just Jakarta, indonesia, and iLight Marina Bay in submissions and represent a selection beginning to be known. Like all the other Singapore. of the best contemporary art in Prudential Eye exhibitions, Prudential 3D Tic-Tac-Toe is an interactive light sculpture Singapore. Prudential Singapore Eye is Singapore Eye aims to bring to light which allows multiple players of all ages to the first major exhibition in a year of a new and exciting contemporary art play Tic-Tac-Toe with one another. cultural celebrations of the nation’s 50th scene and foster greater appreciation of anniversary. Singapore’s visual art scene both locally and internationally. 3D Tic-Tac-Toe, 2014 The works of the exhibiting artists demonstrate versatility, with many of the artists working experimentally Jeremy Sharma Jeremy Sharma works primarily as a conceptual painter. -

Shaping Visions Unites Expressions of Lived and Natural Environments by Five Celebrated Cultural Medallion Recipients

PRESS RELEASE STPI Gallery’s Annual Special Exhibition Shaping Visions unites expressions of lived and natural environments by five celebrated Cultural Medallion recipients Opens to Public: Sunday, 27 Sep – Sunday, 15 Nov 2020 STPI Gallery Free Entry Shaping Visions STPI Gallery is delighted to present its Annual Special Exhibition 2020, Shaping Visions. This year, STPI proudly looks close to home with its selection of five extraordinary artists in Singapore: the late master of Chinese ink Chua Ek Kay; pioneering collage artist Goh Beng Kwan; leading sculptor Han Sai Por; seminal performance artist Amanda Heng; and renowned watercolour painter Ong Kim Seng. Shaping Visions marks the first time these distinguished practitioners — who have each been awarded The Cultural Medallion, the nation’s highest honour for arts and culture practitioners — exhibit together, in an ode to their immense artistic contributions. A testimony of artistic sensibilities and achievements across time Shaping Visions unites each artist’s distinct depictions showcases each artist’s trail-blazing style and expert of natural and built environments, shedding light command of media and materials. As the artists hail on personal reflections of and postures towards an from backgrounds that are largely not printmaking- evolving society. centric, the exhibition will feature a diverse range of expressions that invite moments of pause, suspension By bringing together existing, signature pieces as well and perception. as print-based works produced during their respective residencies -

Art of Tang Da Wu

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Body and communication : the ‘ordinary’ art of Tang Da Wu Wee, C. J. Wan‑Ling 2018 Wee, C. J. W.‑L. (2018). Body and communication : the ‘ordinary’ artof Tang Da Wu. Theatre Research International, 42(3), 286‑306. doi:10.1017/S0307883317000591 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/144518 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0307883317000591 © 2018 International Federation for Theatre Research. All rights reserved. This paper was published by Cambridge University Press in Theatre Research International and is made available with permission of International Federation for Theatre Research. Downloaded on 27 Sep 2021 10:02:22 SGT Accepted and finalized version of: Wee, C. J. W.-L. (2018). ‘Body and communication: The “Ordinary” Art of Tang Da Wu’. Theatre Research International, 42(3), 286-306. C. J. W.-L. Wee [email protected] Body and Communication: The ‘Ordinary’ Art of Tang Da Wu Abstract What might the contemporary performing body look like when it seeks to communicate and to cultivate the need to live well within the natural environment, whether the context of that living well is framed and set upon either by longstanding cultural traditions or by diverse modernizing forces over some time? The Singapore performance and visual artist Tang Da Wu has engaged with a present and a region fractured by the predations of unacceptable cultural norms – the consequences of colonial modernity or the modern nation-state taking on imperial pretensions – and the subsumption of Singapore society under capitalist modernization. Tang’s performing body both refuses the diminution of time to the present, as is the wont of the forces he engages with, and undertakes interventions by sometimes elusive and ironic means – unlike some overdetermined contemporary performance art – that reject the image of the modernist ‘artist as hero’. -

ELMER MISA BORLONGAN Artiste Philippin

www.creationcontemporaine-asie.com ELMER MISA BORLONGAN Artiste philippin Elmer Borlongan, Dynamite Kid, oil on canvas, 2012 ELMER MISA BORLONGAN est un artiste contemporain philippin, connu pour son expressionisme figuratif. Il a obtenu de multiples prix dont le Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) 13 Artist Award en 1994 et le 2004 Award for Continuing Excellence and Service, Metrobank Foundation. De nombreux travaux de l’artiste ont été vendus aux enchères comme 'Quiapo' vendu 209.385 $, son record, par la Leon Gallery, Makati, lors de 'The Magnificent September Auction 2016'. L’ARTISTE Elmer Borlongan est né en 1967 à Manille. Il s’est formé à la peinture sous la direction de Fernando Sena dès l’âge de 11 ans. Il est diplômé de l’University of the Philippines' College of Fine Arts (Major in Painting) (1987). Elmer Borlongan et sa femme, artiste, Plet C. Bolipata, vivent à San Antonio, Zambales. SON OEUVRE Elmer Borlongan peint des histoires du quotidien, de survie et d’endurance au milieu de la pauvreté et du désespoir. Son travail est caractérisé par une figuration stylisée, des têtes chauves, de grands yeux et des membres allongés. Elmer Borlongan a passé son enfance dans les centres-villes urbains de Manille. De fait, ses sensibilités, son choix de sujets et de thèmes, étaient dès le début en phase avec les luttes quotidiennes de la classe ouvrière philippine. C'est surtout sa représentation des sans- abris et des enfants des rues qui a attiré l'attention du monde de l’art philippin sur le jeune artiste au début des années 1990.