The Black Body As Archive of Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young-Voices-2019.Pdf

2019 young voices /youngvoices The Beast Within Cathy Lu, 17 welcome to young voices 2019 GET PUBLISHED! The writing and art in this magazine was created by in Young Voices 2020 talented young people from all across Toronto. Love what you’re reading here? Their humour, compassion, anger and intelligence Want to be part of it? make these pages crackle and shine. Whether their Submit stories, poems, rants, pieces are about technology, racism, nature, despair, or artwork, comics, photos... love, their expression is clear, passionate and original. Making art is often a solitary pursuit, and for many Submit NOW! See page 79 for details. writers and artists in this magazine, this is the first time they’ve shared their work with a broad audience. As the audience, you’ll find poems and photos, drawings and essays that will challenge you to see the world from Cover Art by new perspectives and maybe inspire you to make your Alicia Tian, 17 own voice heard. All the pieces in the magazine were selected by teens working with professional writer/artist mentors on editorial teams. A big thank you to them all for the thoughtfulness and care they brought to their work. The Young Voices 2019 editorial board: Lillian Allen Mahak Jain Jareeat Purnava Rishona Altenberg Juanita Lam Ken Sparling Zawadi Bunzigiye Olivia Li Phoebe Tsang Leia Kook Chen Wenting Li Patrick Walters Kathryn Dou Barton Lu Chloe Xuan Bessa Fan Furqan Mohamed Maria Yang Lucy Haughton Sachiko Murakami Rain YeYang Monidipa Nath The Young Voices program is supported through the generosity of the Daniels brothers in honour of their mother, Norine Rose, and the Friends of Toronto Public Library, South Chapter. -

LCSH Section J

J (Computer program language) J. I. Case tractors Thurmond Dam (S.C.) BT Object-oriented programming languages USE Case tractors BT Dams—South Carolina J (Locomotive) (Not Subd Geog) J.J. Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) J. Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) BT Locomotives USE Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) UF Clark Hill Lake (Ga. and S.C.) [Former J & R Landfill (Ill.) J.J. "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) heading] UF J and R Landfill (Ill.) UF "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clark Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) J&R Landfill (Ill.) Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clarks Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) BT Sanitary landfills—Illinois BT Public buildings—Texas Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) J. & W. Seligman and Company Building (New York, J. James Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) BT Lakes—Georgia USE Banca Commerciale Italiana Building (New UF Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Lakes—South Carolina York, N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) Reservoirs—Georgia J 29 (Jet fighter plane) BT Public buildings—Nebraska Reservoirs—South Carolina USE Saab 29 (Jet fighter plane) J. Kenneth Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) J.T. Berry Site (Mass.) J.A. Ranch (Tex.) UF Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) UF Berry Site (Mass.) BT Ranches—Texas BT Post office buildings—Virginia BT Massachusetts—Antiquities J. Alfred Prufrock (Fictitious character) J.L. Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, N.C.) J.T. Nickel Family Nature and Wildlife Preserve (Okla.) USE Prufrock, J. Alfred (Fictitious character) UF Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, UF J.T. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Great Movie Soundtracks, Part 2

Great movie soundtracks brought to you by HOOPLA! With HOOPLA, you can stream movies, television, e-books, audiobooks and comics – and also music. They carry over 7000 soundtracks, so I narrowed it down to my twenty favorites. Here’s part two of my favorites. La La Land (2016) Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling star Mia, an aspiring actress/barista, and Sebastian, a struggling jazz musician, who fall in love in backdrop of Los Angeles; an homage to the old musicals with a modern twist. The Oscar winning soundtrack includes original, catchy tunes, my favorite being the opening number “Another Day of Sun” – a dance sequence filmed on a real LA Freeway. The Mambo Kings (1992) Armand Assante and Antonio Banderas star as the musician brothers Cesar and Nestor who leave Cuba for America in the 1950’s, hoping to hit the top of the Latin music scene. Soundtrack features many big names from the world of latin jazz and salsa music, including songs by Arturo Sandoval, Celia Cruz, Tito Puente, and Mambo All-Stars. Mamma Mia! (2008) A bride-to-be tries to find her real father told using hit songs by the popular 1970’s group ABBA. If you need an ABBA fix, here it is. National Lampoon's Animal House (1978) John Belushi stars in one of the most irreverent, politically incorrect comedies of all time - follows a group of rowdy fraternity brothers at the fictional Faber College in 1962 and all their shenanigans. Soundtrack includes early sixties classics by Sam Cooke, Lloyd Williams, Paul & Paula, and Stephen Bishop. -

Where Was the Outrage? the Lack of Public Concern for The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by TopSCHOLAR Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 8-2014 Where Was the Outrage? The Lack of Public Concern for the Increasing Sensationalism in Marvel Comics in a Conservative Era 1978-1993 Robert Joshua Howard Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Howard, Robert Joshua, "Where Was the Outrage? The Lack of Public Concern for the Increasing Sensationalism in Marvel Comics in a Conservative Era 1978-1993" (2014). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1406. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1406 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHERE WAS THE OUTRAGE? THE LACK OF PUBLIC CONCERN FOR THE INCREASING SENSATIONALISM IN MARVEL COMICS IN A CONSERVATIVE ERA 1978-1993 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Robert Joshua Howard August 2014 I dedicate this thesis to my wife, Marissa Lynn Howard, who has always been extremely supportive of my pursuits. A wife who chooses to spend our honeymoon fund on a trip to Wyoming, to sit in a stuffy library reading fan mail, all while entertaining two dogs is special indeed. -

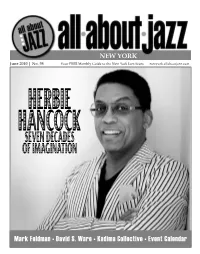

June 2010 Issue

NEW YORK June 2010 | No. 98 Your FREE Monthly Guide to the New York Jazz Scene newyork.allaboutjazz.com HERBIE HANCOCKSEVEN DECADES OF IMAGINATION Mark Feldman • David S. Ware • Kadima Collective • Event Calendar NEW YORK Despite the burgeoning reputations of other cities, New York still remains the jazz capital of the world, if only for sheer volume. A night in NYC is a month, if not more, anywhere else - an astonishing amount of music packed in its 305 square miles (Manhattan only 34 of those!). This is normal for the city but this month, there’s even more, seams bursting with amazing concerts. New York@Night Summer is traditionally festival season but never in recent memory have 4 there been so many happening all at once. We welcome back impresario George Interview: Mark Feldman Wein (Megaphone) and his annual celebration after a year’s absence, now (and by Sean Fitzell hopefully for a long time to come) sponsored by CareFusion and featuring the 6 70th Birthday Celebration of Herbie Hancock (On The Cover). Then there’s the Artist Feature: David S. Ware always-compelling Vision Festival, its 15th edition expanded this year to 11 days 7 by Martin Longley at 7 venues, including the groups of saxophonist David S. Ware (Artist Profile), drummer Muhammad Ali (Encore) and roster members of Kadima Collective On The Cover: Herbie Hancock (Label Spotlight). And based on the success of the WinterJazz Fest, a warmer 9 by Andrey Henkin edition, eerily titled the Undead Jazz Festival, invades the West Village for two days with dozens of bands June. -

The Case of Imposed Identity for Multiracial Individuals

YOUR PERCEPTION, MY REALITY: THE CASE OF IMPOSED IDENTITY FOR MULTIRACIAL INDIVIDUALS A Dissertation by NICHOLE CRYSTELL BOUTTÉ-HEINILUOMA Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2012 Major Subject: Sociology Your Perception, My Reality: The Case of Imposed Identity for Multiracial Individuals Copyright 2012 Nichole Crystell Boutté-Heiniluoma YOUR PERCEPTION, MY REALITY: THE CASE OF IMPOSED IDENTITY FOR MULTIRACIAL INDIVIDUALS A Dissertation by NICHOLE CRYSTELL BOUTTÉ-HEINILUOMA Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joe Feagin Committee Members, Sarah Gatson Alex McIntosh Jane Sell Head of Department, Jane Sell August 2012 Major Subject: Sociology iii ABSTRACT Your Perception, My Reality: The Case of Imposed Identity for Multiracial Individuals. (August 2012) Nichole Crystell Boutté-Heiniluoma, B.A., Texas A&M University; M.I.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joe Feagin Prior to this exploratory study, issues of multiracial identity development and imposed identity had not been explored in great detail. This study sought to expand the current knowledge base by offering an examination of a) multiracial identity development for different bi/multiracial backgrounds, b) the influence of the perception of race on social interactions (imposed identity), and c) racial identification in the public and private spheres from the perspective of multi-racial individuals. A literature based survey was developed and piloted with an expert panel to increase face and content validity. -

2020 PRODUCT CATALOG 2 Call Sales Support at 800-325-7354 Page 04 Introduction TABLE 06 PRE-PEN® (Benzylpenicilloyl Polylysine Injection USP)

2020 PRODUCT CATALOG 2 Call Sales Support at 800-325-7354 page 04 Introduction TABLE 06 PRE-PEN® (benzylpenicilloyl polylysine injection USP) 07 Center-Al® (allergenic extract, alum precipitated) OF 08 Sublingual Immunotherapy Tablets 09 ODACTRA® CONTENTS 10 GRASTEK® 11 RAGWITEK® 12 Allergen Extracts 13 Pollen Extracts 16 Pollen Mixes 17 Molds 17 Smuts 18 Insects 18 Epidermals 19 Foods/Ingestants 21 Standardized Extracts 22 Pollen 22 Pollen Mixes 22 Epidermals 22 Mites 23 Ancillary Products 24 Normal Saline with Phenol (NSP) 24 Albumin Saline with Phenol (HSA) 24 50% Glycerin 25 Sterile Empty Vials (SEV) 26 Amber Sterile Empty Vials (SEV) 27 Non-Sterile Dropper Vials, Dropper Tips, Pumps 28 Colored Caps for Vials 28 Miscellaneous (labels, information sheets, etc.) 29 Allergy Diagnostics 29 Diagnostic Controls 29 Skin Testing Systems 30 Syringes 30 Mixing Syringes 30 Safety Syringes 30 Standard Syringes 31 Trays 32 Package Inserts 57 Fax Order Form 58 Ordering Information You are encouraged to report patient reactions to skin testing and/or immunotherapy to ALK. Our contact information is toll-free 1-855-216-6497 or email [email protected] ALK is a global allergy solutions company, with a wide range of allergy treatments, products and services that meet the unique needs of allergy sufferers, their families and healthcare professionals. ALK is committed to helping as many people with allergy as possible, which means providing your practice with quality supplies and services to help your business thrive and provide your patients with educational materials to support immunotherapy awareness and improve compliance. From our extensive selection of allergy extracts, skin testing devices, unique products, and patient resources, we are committed to helping you improve the lives of more allergic patients. -

The “Pop Pacific” Japanese-American Sojourners and the Development of Japanese Popular Music

The “Pop Pacific” Japanese-American Sojourners and the Development of Japanese Popular Music By Jayson Makoto Chun The year 2013 proved a record-setting year in Japanese popular music. The male idol group Arashi occupied the spot for the top-selling album for the fourth year in a row, matching the record set by female singer Utada Hikaru. Arashi, managed by Johnny & Associates, a talent management agency specializing in male idol groups, also occupied the top spot for artist total sales while seven of the top twenty-five singles (and twenty of the top fifty) that year also came from Johnny & Associates groups (Oricon 2013b).1 With Japan as the world’s second largest music market at US$3.01 billion in sales in 2013, trailing only the United States (RIAJ 2014), this talent management agency has been one of the most profitable in the world. Across several decades, Johnny Hiromu Kitagawa (born 1931), the brains behind this agency, produced more than 232 chart-topping singles from forty acts and 8,419 concerts (between 2010 and 2012), the most by any individual in history, according to Guinness World Records, which presented two awards to Kitagawa in 2010 (Schwartz 2013), and a third award for the most number-one acts (thirty-five) produced by an individual (Guinness World Record News 2012). Beginning with the debut album of his first group, Johnnys in 1964, Kitagawa has presided over a hit-making factory. One should also look at R&B (Rhythm and Blues) singer Utada Hikaru (born 1983), whose record of four number one albums of the year Arashi matched. -

Creative Cosmetics, 2Nd Edition, English Illustrations: Ashley Greenleaf and Thames & Kosmos LLC

EXPERIMENT MANUAL Please observe the safety information below, the advice for supervising adults on page 1, the safety rules on page 3, and the information about hazardous substances (chemicals) and their environmentally sound disposal, the first aid information, and the other safety information on the inside front cover. WARNING. Not suitable for children under 8 years. For use under adult supervision. Read the instructions before use, follow them and keep them for reference. Keep the kit out of reach of children under 8 years old. Contains glass that may break. Contains some chemicals which present a hazard to health. Do not allow chemicals to come into contact with any part of the body, particularly the mouth and eyes (except as instructed in the manual). Keep small children and animals away from experiments. WARNING — This set contains chemicals that may be harmful if misused. Read cautions on individual containers and in manual carefully. Not to be used by children except under adult supervision. Franckh-Kosmos Verlags-GmbH & Co. KG, Pfizerstr. 5-7, 70184 Stuttgart, Germany | +49 (0) 711 2191-0 | www.kosmos.de Thames & Kosmos, 301 Friendship St., Providence, RI, 02903, USA | 1-800-587-2872 | www.thamesandkosmos.com Thames & Kosmos UK Ltd, Goudhurst, Kent, TN17 2QZ , United Kingdom | 01580 212000 | www.thamesandkosmos.co.uk › › › SAFETY INFORMATION Warning! • Parts in this kit have functional sharp points, corners, or edges. There is a risk of injury. • Always store this experiment kit in a cool place that is inaccessible for small children. Always close containers tightly and keep them away from sources of ignition or open flames (e.g. -

Homosocial Hunger in Blaxploitation Film and Pornography

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Genealogies of the Stud: Homosocial Hunger in Blaxploitation Film and Pornography Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0ss28816 Author Ali, Mohammed Syed Publication Date 2016 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Genealogies of the Stud: Homosocial Hunger in Blaxploitation Film and Pornography THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History by Mohammed Syed Ali Thesis Committee: Assistant Professor Allison Perlman, Chair Assistant Professor Emily Thuma Associate Professor Sharon Block 2016 © 2016 Mohammed Syed Ali DEDICATION To my friends, family, and fellow troublemakers. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS vi INTRODUCTION: The Subject of Gender 1 SOURCES AND METHODS 6 PART 1: Theoretical Lens: Narratives of Genre, Dialectics of Pornography 9 Blaxploitation and Pornography, Men and Masculinity 12 Homosocial Hunger: Desire and Consumption Between Men 19 PART 2: Black and White Male Appetites: Disciplined Consumption and Utopian Hungers in Black is Beautiful 25 PART 3: Blackness and Gender: Politics and Palatability in Sweet Sweetback’s Badaaassss Song 35 PART 4: Between Black and White Men: Homosocial Hunger and Class Anxiety in Shaft and Lialeh 53 CONCLUSION: Epistemologies of Hunger 69 REFERENCES 73 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 3.1 Sweetback Before Removing Bra 42 Figure 3.2 Sweetback Removing Bra (Before Transition) 43 Figure 3.3 Sweetback Removing Bra (After Transition) 44 Figure 4.1 Shaft’s Girlfriend on the Couch 58 Figure 4.2 Buford Sleeping in the Girls’ Room 59 Figure 4.3 Arlo Seduces Rogers 62 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my heartfelt thanks to my committee chair, Professor Allison Perlman, for her critical insights, labor, and time. -

Addressing the 'C' in Aces Webinar Transcript

Mighty Fine, MPH, CHES, moderator: Hello, everyone, my name is Mighty Fine and I’m the director of the Center for Public Health Practice and Professional Development at the American Public Health Association. I’m pleased to be with you all today for our webinar, “Addressing the “C” in ACEs, Combating the Nation's Silent Crisis.” So, I’d just like to say that we have quite the lineup for you all today so hopefully you'll engage with us through the chat feature. Type in your questions as we move through the day. We will be together for quite some time and we want to make sure that you are a part of this dialogue, so please be sure to type any questions or comments in the chat feature and we will be tracking them. Today's webinar has been approved for 3.5 continuing education credits and we want to disclose that none of the speakers or the planners have any conflict of interest to disclose. Again, just some of the accreditation statements for your reference; we will be offering CME, CNE, C PH, CHES, and if you want a certificate of participation, you can get one of those as well. Please keep in mind, after the close of this webinar you will receive information on a link to claim your credits. And you must do so before the deadline of June 14, 2021 in order to obtain the credits. Be sure to do that before the system closes otherwise you won't be able to get those 3.5 credits.