Constructing Identity Between the Myths of Black Inferiority and a Post-Racial America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extensions of Remarks 10509

May 9, 1979 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 10509 MENT REPORT.-The Secretary shall set forth available to the United States Geological -Page 274, line 1, strike "(b) (1)" and in in each report to the Congress under the Survey, the Bureau of Mines, or any other lieu thereof insert "(c) (2)". Mining and Minerals Policy Act of 1970 a agency or instrumentality of the United Page 333, lines 14 and 15, strike "after the summary of the pertinent information States. date of enactment of this Act". (other than proprietary or other confidential (Additional technical amendments to -Page 275, line 8, change "28" to "27" and information) relating to minerals which is Udall-Anderson substitute (H.R. 3651) .) change "33" to "34". EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS A NONFUEL MINERAL POLICY: WE Of course, the usual antagonists are lined These Americans descend from .Japa CAN NO LONGER WAIT up on each side of this policy debate. But, nese, Chinese, Korean, and Filipino an as Nevada Congressman J. D. Santini points cestors, as well as from Hawaii and t'iher out in our p . 57 feature, their arguments Pacific Islands such as Samoa, Fiji, and HON. JIM SANTINI go by one another like ships in the night with nothing happening-until the lid blows Tahiti. In southern California, where OF NEVADA off. we have the greatest concentration of IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES But, how do you get the public excited Asian and Pacific Americans anywhere Wednesday, May 9, 1979 about metal shortages? in the Nation, their valuable involvemept Even Congressman Santini's well-meant in the growth and prosperity of our local • Mr. -

Black Protectionism As a Civil Rights Strategy

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository UF Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship Winter 2005 Black Protectionism as a Civil Rights Strategy Katheryn Russell-Brown University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Katheryn Russell-Brown, Black Protectionism as a Civil Rights Strategy, 53 Buff. L. Rev. 1 (2005), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/82 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UF Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUFFALO LAW REVIEW VOLUME 53 WINTER 2005 NUMBER 1 Black Protectionism as a Civil Rights Strategy' KATHERYN RUSSELL-BROWNt "I AM A MAN"2 INTRODUCTION "Aren't things better today than they were fifty years ago?" This is a common rhetorical query posed by those who 1. This Article presents an expanded analysis of the chapter Black Protectionism, in KATHERYN RUSSELL-BROWN, UNDERGROUND CODES: RACE, CRIME, AND RELATED FIRES 72-96 (2004). t Professor of Law and Director, Center for the Study of Race and Race Relations, University of Florida, Levin College of Law, Gainesville, FL 32611 ([email protected]). The author wishes to thank her husband, Kevin K. Brown, for helping to make the connection between routine news reports of Black offending and the appeal of Black protectionism, and the role that Black organizations play in the exercise of protectionism; her parents, Tanya H. -

Young-Voices-2019.Pdf

2019 young voices /youngvoices The Beast Within Cathy Lu, 17 welcome to young voices 2019 GET PUBLISHED! The writing and art in this magazine was created by in Young Voices 2020 talented young people from all across Toronto. Love what you’re reading here? Their humour, compassion, anger and intelligence Want to be part of it? make these pages crackle and shine. Whether their Submit stories, poems, rants, pieces are about technology, racism, nature, despair, or artwork, comics, photos... love, their expression is clear, passionate and original. Making art is often a solitary pursuit, and for many Submit NOW! See page 79 for details. writers and artists in this magazine, this is the first time they’ve shared their work with a broad audience. As the audience, you’ll find poems and photos, drawings and essays that will challenge you to see the world from Cover Art by new perspectives and maybe inspire you to make your Alicia Tian, 17 own voice heard. All the pieces in the magazine were selected by teens working with professional writer/artist mentors on editorial teams. A big thank you to them all for the thoughtfulness and care they brought to their work. The Young Voices 2019 editorial board: Lillian Allen Mahak Jain Jareeat Purnava Rishona Altenberg Juanita Lam Ken Sparling Zawadi Bunzigiye Olivia Li Phoebe Tsang Leia Kook Chen Wenting Li Patrick Walters Kathryn Dou Barton Lu Chloe Xuan Bessa Fan Furqan Mohamed Maria Yang Lucy Haughton Sachiko Murakami Rain YeYang Monidipa Nath The Young Voices program is supported through the generosity of the Daniels brothers in honour of their mother, Norine Rose, and the Friends of Toronto Public Library, South Chapter. -

Black Heroes in the United States: the Representation of African Americans in Contemporary American Culture

Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue Moderne per la Comunicazione e la Cooperazione Internazionale Classe LM-38 Tesi di Laurea Black Heroes in the United States: the Representation of African Americans in Contemporary American Culture Relatore Laureando Prof.ssa Anna Scacchi Enrico Pizzolato n° matr.1102543 / LMLCC Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 - 1 - - 2 - Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue Moderne per la Comunicazione e la Cooperazione Internazionale Classe LM-38 Tesi di Laurea The Representation of Black Heroism in American Culture Relatore Laureando Prof.ssa Anna Scacchi Enrico Pizzolato n° matr.1102543 / LMLCC Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 - 4 - Table of Contents: Preface Chapter One: The Western Victimization of African Americans during and after Slavery 1.1 – Visual Culture in Propaganda 1.2 - African Americans as Victims of the System of Slavery 1.3 - The Gift of Freedom 1.4 - The Influence of White Stereotypes on the Perception of Blacks 1.5 - Racial Discrimination in Criminal Justice 1.6 - Conclusion Chapter Two: Black Heroism in Modern American Cinema 2.1 – Representing Racial Agency Through Passive Characters 2.2 - Django Unchained: The Frontier Hero in Black Cinema 2.3 - Character Development in Django Unchained 2.4 - The White Savior Narrative in Hollywood's Cinema 2.5 - The Depiction of Black Agency in Hollywood's Cinema 2.6 - Conclusion Chapter Three: The Different Interpretations -

The Lady Onstage by Erin Bregman

The Lady Onstage by Erin Bregman Resource Guide for Teachers Created by: Lauren Bloom Hanover, Director of Education Jeff Denight, Dramaturgy Intern 1 Table of Contents About Profile Theatre 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 The Artists 5 Lesson 1: Historical Context 6 Classroom Activities: 1) Biography and Context 6 2) Knipper and Chekov in Their Own Words 6 3) The Development of The Lady Onstage 8 4) Considering Contemporary Cultural Shifts (Homework) 9 Supplemental Materials 10 Lesson 2: The Process of Play Development 21 Classroom Activities 1) Where Do New Plays Come From? 21 2) Exploring a Play We Know 23 3) How to Start - the Development Process in Action 24 4) Starting Your Own Play (Homework) 24 Supplemental Materials 26 Lesson 3: One Person Plays - A Unique Challenge 34 Classroom Activities 1) Exploring Single-Character Monologues 34 2) Exploring Multi-character Solo Performances 35 3) Writing Your Own Monologue (Homework) 36 Supplemental Materials 38 Lesson 4: Chekhov Today: Translations and Adaptations 41 Classroom Activities 1) Exploring Translations 42 2) Exploring Work Inspired by Chekhov 42 3) Creating Your Own Adaptation 43 Supplemental Materials 44 Lesson 5: Reflecting on the Performance Classroom Activities 1) Classroom Discussion and Reflection 52 2) What We’ve Learned 52 3) Creative Writing (Homework) 53 2 About Profile Theatre Profile Theatre was founded in 1997 with the mission of celebrating the playwright’s contribution to live theater. Each year Profile produces a season of plays devoted to a single playwright, engaging with our community to explore that writer’s vision and influence on theatre and the world at large. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Here I Come with All My Black Girl Magic”: Black Women and Girls’ Experiences in Predominantly White Independent Private Schools

“HERE I COME WITH ALL MY BLACK GIRL MAGIC”: BLACK WOMEN AND GIRLS’ EXPERIENCES IN PREDOMINANTLY WHITE INDEPENDENT PRIVATE SCHOOLS BY DEVEAN R. OWENS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education Policy, Organization and Leadership with a concentration in Diversity and Equity in Education in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2020 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Anjalé Welton, Chair Professor Ruth Nicole Brown Professor Adrienne Dixson Professor Helen Neville Abstract Within independent private schools specifically, Black women and girls endure feelings of rejection, isolation, and inadequacy all whilst trying to maintain their academic or career success and a positive self-perception. Through the lenses of Black Feminist Thought and Critical Race Theory, this dissertation presents Black women and girls’ true experiences in PWIS which defy dominant deficit beliefs. Participants detailed the racism, erasure, and trauma they endured and the detrimental effects these experiences caused in their lives. They also expressed the importance and value of their relationships with one another. These relationships provided them with the affirmation and confidence they needed to believe in and stand up for themselves. Black women and girls engage in various resistance strategies through living authentically, challenging dominant norms, and advocating for themselves and others in the school community. ii Acknowledgements Students & participants… Thank you for inspiring me! Thank you for taking the time to participate in this study. Drs. Welton, Brown, Dixson, Neville, and Zamani-Gallaher… Thank you for challenging me to think more critically and seeing me through this journey. -

Hollywoodland Text.Pdf

HOLLYWOODLAND HOLLYWOODLAND an american fairy tale JENNIFER BANASH Impetus Press PO Box 10025 Iowa City, IA 52240 www.impetuspress.com [email protected] Publisher Note: This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. ISBN 0-9776693-0-0 September 2006 Copyright © 2006 Impetus Press. All rights reserved. for my father I’m going to be in the movies if I have to fuck Bela Lugosi to get there. Actresses are a little like race horses. It’s difficult for us when the race is cancelled. This is an attempt at the ultimate motion picture. ••• 2:00 AM, 82 ° She is in her car when it happens, the black roads around Mulholland winding and twisting, unrolling like the soft dark fabric of a magic carpet. Her eyes blur and she squints them repeatedly, leaning forward to see. The needle on the speedometer flies up past eighty, then ninety, the tendons in her right arm straining, muscles burning as she grips the wheel one-handed. Sierra loves to drive more than anything, the feeling of weightlessness, careening through the air, unstoppable. She was fucking unstoppable. She could feel the kid in the seat next to her getting nervous, moving back and forth in his seat, one hand clutching the belt that cut across his skinny frame. His jeans make a harsh scraping sound. The rasp of denim on leather annoys her, and she closes her eyes. -

Race Trouble: an Exploration of Race Relations in Zebra Crossing, Coconut and the Book of Memory by Meg Vandermerwe, Kopano Matlwa and Petina Gappah

Race Trouble: An exploration of race relations in Zebra Crossing, Coconut and The Book of Memory by Meg Vandermerwe, Kopano Matlwa and Petina Gappah Travis McCabe March 2020 English Studies College of Arts Faculty of Humanities Pietermaritzburg Campus University of Kwa-Zulu Natal 1 DECLARATION Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, in the Graduate Programme in English Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. I, Travis McCabe, declare that 1. The research reported in this thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original research. 2. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. 3. This thesis does not contain other persons’ data, pictures, graphs or other information, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. 4. This thesis does not contain other persons' writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted, then: a. Their words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been referenced b. Where their exact words have been used, then their writing has been placed in italics and inside quotation marks, and referenced. 5. This thesis does not contain text, graphics or tables copied and pasted from the Internet, unless specifically acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the thesis and in the References sections. 12 March 2020 Travis McCabe Supervisor: 214542406 Dr Claire Scott _______________ _______________ Signature Signature 2 Abstract Despite the formalised abolishment of both apartheid and colonialism, it would in many respects be remiss to conclude that the legacy of these systems of oppression do not continue to exert some level of influence on the attitudes and behaviour of individuals and groups. -

Welcome, We Have Been Archiving This Data for Research And

Welcome, To our MP3 archive section. These listings are recordings taken from early 78 & 45 rpm records. We have been archiving this data for research and preservation of these early discs. ALL MP3 files can be sent to you by email - $2.00 per song Scroll until you locate what you would like to have sent to you, via email. If you don't use Paypal you can send payment to us at: RECORDSMITH, 2803 IRISDALE AVE RICHMOND, VA 23228 Order by ARTIST & TITLE [email protected] H & H - Deep Hackberry Ramblers - Crowley Waltz Hackberry Ramblers - Tickle Her Hackett, Bobby - New Orleans Hackett, Buddy - Advice For young Lovers Hackett, Buddy - Chinese Laundry (Coral 61355) Hackett, Buddy - Chinese Rock and Egg Roll Hackett, Buddy - Diet Hackett, Buddy - It Came From Outer Space Hackett, Buddy - My Mixed Up Youth Hackett, Buddy - Old Army Routine Hackett, Buddy - Original Chinese Waiter Hackett, Buddy - Pennsylvania 6-5000 (Coral 61355) Hackett, Buddy - Songs My Mother Used to Sing To Who 1993 Haddaway - Life (Everybody Needs Somebody To Love) 1993 Haddaway - What Is Love Hadley, Red - Brother That's All (Meteor 5017) Hadley, Red - Ring Out Those Bells (Meteor 5017) 1979 Hagar, Sammy - (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay 1987 Hagar, Sammy - Eagle's Fly 1987 Hagar, Sammy - Give To Live 1984 Hagar, Sammy - I Can't Drive 55 1982 Hagar, Sammy - I'll Fall In Love Again 1978 Hagar, Sammy - I've Done Everything For You 1978 1983 Hagar, Sammy - Never Give Up 1982 Hagar, Sammy - Piece Of My Heart 1979 Hagar, Sammy - Plain Jane 1984 Hagar, Sammy - Two Sides -

June 2010 Issue

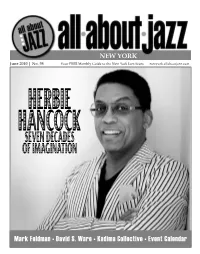

NEW YORK June 2010 | No. 98 Your FREE Monthly Guide to the New York Jazz Scene newyork.allaboutjazz.com HERBIE HANCOCKSEVEN DECADES OF IMAGINATION Mark Feldman • David S. Ware • Kadima Collective • Event Calendar NEW YORK Despite the burgeoning reputations of other cities, New York still remains the jazz capital of the world, if only for sheer volume. A night in NYC is a month, if not more, anywhere else - an astonishing amount of music packed in its 305 square miles (Manhattan only 34 of those!). This is normal for the city but this month, there’s even more, seams bursting with amazing concerts. New York@Night Summer is traditionally festival season but never in recent memory have 4 there been so many happening all at once. We welcome back impresario George Interview: Mark Feldman Wein (Megaphone) and his annual celebration after a year’s absence, now (and by Sean Fitzell hopefully for a long time to come) sponsored by CareFusion and featuring the 6 70th Birthday Celebration of Herbie Hancock (On The Cover). Then there’s the Artist Feature: David S. Ware always-compelling Vision Festival, its 15th edition expanded this year to 11 days 7 by Martin Longley at 7 venues, including the groups of saxophonist David S. Ware (Artist Profile), drummer Muhammad Ali (Encore) and roster members of Kadima Collective On The Cover: Herbie Hancock (Label Spotlight). And based on the success of the WinterJazz Fest, a warmer 9 by Andrey Henkin edition, eerily titled the Undead Jazz Festival, invades the West Village for two days with dozens of bands June. -

Defections by GOP Kill Health Bill For

CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK » TODAY’S ISSUE U DAILY BRIEFING, A2 • TRIBUTES, A5 • WORLD & BUSINESS, B5 • CLASSIFIEDS, B6 • PUZZLES & TV, C3 CLASS B BASEBALL CHAMPION SCRAPPERS ROLL COMING TO COVELLI 50% Baird bests Astro in Game 5 7-run 7th bedevils Batavia Stevie Nicks show set for Sept. 15 OFF SPORTS | B1 SPORTS | B1 VALLEY LIFE | C1 vouchers. DETAILS, A2 FOR DAILY & BREAKING NEWS LOCALLY OWNED SINCE 1869 TUESDAY, JULY 18, 2017 U 75¢ Lordstown police: Pot smuggling via Fusion has occurred before Law enforcement Marijuana bales were found on popular Ford car at rail yard in 2015 seized marijuana in the trunks of Ford By ED RUNYAN ment on Monday Detective Chris Bordonaro of Fusions at dealerships [email protected] provided the de- the Lordstown police said the rail in Portage, Stark LORDSTOWN tails after Jeff Orr, yard notifi ed Lordstown offi cers and Columbiana Last week was not the fi rst time former Trumbull after finding 50 to 100 pounds counties, as well as that marijuana made its way from Ashtabula Group of marijuana attached to the one in Pennsylvania. VINDICATOR The rail car carrying Mexico to the United States inside Law Enforcement EXCLUSIVE Fusion. the Fusions had come the spare-tire compartments of Task Force com- It appeared tape was used to from Hermosillo, Ford Fusions via the CSX rail yard mander, revealed secure the marijuana, and rem- Mexico, and had sat in Lordstown. the case to The Vindicator. nants of the tape were found on idle in Chicago 18 An Aug. 7, 2015, incident at the In that case, bales of marijuana 11 other vehicles, suggesting the hours before coming same rail yard, which is off state were found attached to the un- drugs had been off-loaded from to Lordstown.