The Case of Imposed Identity for Multiracial Individuals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young-Voices-2019.Pdf

2019 young voices /youngvoices The Beast Within Cathy Lu, 17 welcome to young voices 2019 GET PUBLISHED! The writing and art in this magazine was created by in Young Voices 2020 talented young people from all across Toronto. Love what you’re reading here? Their humour, compassion, anger and intelligence Want to be part of it? make these pages crackle and shine. Whether their Submit stories, poems, rants, pieces are about technology, racism, nature, despair, or artwork, comics, photos... love, their expression is clear, passionate and original. Making art is often a solitary pursuit, and for many Submit NOW! See page 79 for details. writers and artists in this magazine, this is the first time they’ve shared their work with a broad audience. As the audience, you’ll find poems and photos, drawings and essays that will challenge you to see the world from Cover Art by new perspectives and maybe inspire you to make your Alicia Tian, 17 own voice heard. All the pieces in the magazine were selected by teens working with professional writer/artist mentors on editorial teams. A big thank you to them all for the thoughtfulness and care they brought to their work. The Young Voices 2019 editorial board: Lillian Allen Mahak Jain Jareeat Purnava Rishona Altenberg Juanita Lam Ken Sparling Zawadi Bunzigiye Olivia Li Phoebe Tsang Leia Kook Chen Wenting Li Patrick Walters Kathryn Dou Barton Lu Chloe Xuan Bessa Fan Furqan Mohamed Maria Yang Lucy Haughton Sachiko Murakami Rain YeYang Monidipa Nath The Young Voices program is supported through the generosity of the Daniels brothers in honour of their mother, Norine Rose, and the Friends of Toronto Public Library, South Chapter. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

If You Are Going to Say You're Afro-Latina That Means That You Are Black

“If you are going to say you’re Afro-Latina that means that you are Black”: Afro-Latinxs Contesting the Dilution of Afro-Latinidad Rene Ayala Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Final Research Paper 15 May 2019 Ayala 1 The second half of the 2010’s has brought an increase in the visibility of, and conversations about, Afro-Latinx identity in the United States. Afro-Latinx, in its simplest definition, is a term that describes Latin Americans and Latin American Descendants who are of African Descent. While Afro-Latinidad as a concept and an identity has existed for decades, both in Latin America and the United States, the current decade has brought many advances in terms of the visibility of Afro-Latinidad and Afro-Latinx people in the United States. Univision, one of the five main Spanish language news channels targeted towards Latinxs living the United States, in late 2017 promoted Ilda Calderon, an Afro-Colombian news anchor, to main news anchor on their prime-time news program Noticiero Univsion (Hansen 2017). This promotion makes her the first Afro-Latina to anchor the news in Univsion’s history as well as the first Afro-Latina to anchor in any major network in the U.S. The decision comes at the heel of the networks airing of Calderon’s interview with a Ku Klux’s Klan Leader in August of 2017 (Univision 2017). The interview was particularly interesting because it showed the complexities of Afro-Latinidad to their Latinx audience. The network has historically been criticized for their exclusion and erasure of Afro-Latinxs in both their coverage of news that occurs in Latin America and the U.S. -

Defining Race: Addressing the Consequences of the Law’S Failure to Define Race

PEERY.38.5.4 (Do Not Delete) 6/2/2017 2:55 PM (RE)DEFINING RACE: ADDRESSING THE CONSEQUENCES OF THE LAW’S FAILURE TO DEFINE RACE Destiny Peery† Modern lawmakers and courts have consistently avoided discussing how to define race for legal purposes even in areas of law tasked regularly with making decisions that require them. This failure to define what race is in legal contexts specifically requiring such determinations, and in the law more broadly, creates problems for multiple actors in the legal system, from plaintiffs deciding whether to pursue claims of discrimination, lawyers deciding how to argue cases, and legal decision-makers deciding cases where race is not only relevant but often central to the legal question at hand. This Article considers the hesitance to engage with questions of racial definition in law. Drawing on findings from social psychology to demonstrate how race can be defined in multiple ways that may produce different categorizations, this Article argues that the lack of racial definition is problematic because it leaves a space for multiple definitions to operate below the surface, creating not only problematic parallels to a bad legal past but also producing inconsistency. The consequences of this continued ambiguity is illustrated through an ongoing dilemma in Title VII anti-discrimination law, where the courts struggle to interpret race, illustrating the general problems created by the law’s refusal to define race, demonstrating the negative impact on individuals seeking relief and the confusion created as different definitions of race are applied to similar cases, producing different outcomes in similar cases. -

Thin Lizzy Colour Match Kit

Thin Lizzy Colour Match Kit Find the perfect shade of 6in1, Mineral Foundation or Concealer Crème to match your skin tone. Finding the shade that’s right for you: Our skin tone and complexion can change throughout the season, so you may be one shade in winter and a slightly darker shade in summer with the increase of sun exposure. To find your perfect shade: Swipe the colours that look closest to your skin tone on your jaw line down to your neck. The shade that matches your neck is the one you should choose. Warm or Cool Tones: Do you wear fake tan? If so you may need to go a shade darker than your regular colour and a warm tone will probably blend in better. For Rosy / Cool Skin tones – for skin that blushes or burns easily For Fair Skin For Medium Skin Light Skin with Pink undertones Medium Skin with yellow undertones Tends to look better with Silver jewellery Tends to look better with Gold jewellery Celebrity reference: Drew Barrymore, Celebrity reference: Cameron Diaz, Kate Winslet Celine Dion, Kate Hudson For Olive / War Skin tones – for skin that tans easily without burning For very fair skin For Fair Skin Light Skin with Pink undertones Light Skin with neutral undertones Tends to look better with Silver jewellery Always burns before tanning Celebrity reference: Kate Middleton Celebrity reference: Adele, Amy Adams, Taylor Jennifer Anniston Swift For Medium Skin For Medium-Dark Skin Medium Skin with Yellow undertones Very Gold, Light Tan, Honey Skin tones Tends to look better with Gold Jewellery Common shade in Mediterranean / Latin Celebrity reference: Diane Kruger, Celine Dion demographic, tans easily Lucy Liu, Penelope Cruz Celebrity reference: Kim Kardashian, Paula Patton, Halle Berry For Dark Skin For Deep Dark Skin Tan with neutral undertones, deep olive skin tones Rich brown with yellow undertones Common Shade in African American demographic, Common Shade in Pacific Island demographic Tans very easily Celebrity reference: Janet Jackson Celebrity reference: Jennifer Lopez Mary J. -

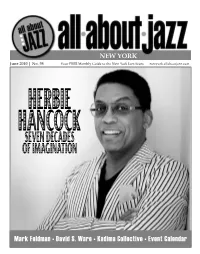

June 2010 Issue

NEW YORK June 2010 | No. 98 Your FREE Monthly Guide to the New York Jazz Scene newyork.allaboutjazz.com HERBIE HANCOCKSEVEN DECADES OF IMAGINATION Mark Feldman • David S. Ware • Kadima Collective • Event Calendar NEW YORK Despite the burgeoning reputations of other cities, New York still remains the jazz capital of the world, if only for sheer volume. A night in NYC is a month, if not more, anywhere else - an astonishing amount of music packed in its 305 square miles (Manhattan only 34 of those!). This is normal for the city but this month, there’s even more, seams bursting with amazing concerts. New York@Night Summer is traditionally festival season but never in recent memory have 4 there been so many happening all at once. We welcome back impresario George Interview: Mark Feldman Wein (Megaphone) and his annual celebration after a year’s absence, now (and by Sean Fitzell hopefully for a long time to come) sponsored by CareFusion and featuring the 6 70th Birthday Celebration of Herbie Hancock (On The Cover). Then there’s the Artist Feature: David S. Ware always-compelling Vision Festival, its 15th edition expanded this year to 11 days 7 by Martin Longley at 7 venues, including the groups of saxophonist David S. Ware (Artist Profile), drummer Muhammad Ali (Encore) and roster members of Kadima Collective On The Cover: Herbie Hancock (Label Spotlight). And based on the success of the WinterJazz Fest, a warmer 9 by Andrey Henkin edition, eerily titled the Undead Jazz Festival, invades the West Village for two days with dozens of bands June. -

Notions of Beauty & Sexuality in Black Communities in the Caribbean and Beyond

fNotions o Beauty & Sexuality in Black Communities IN THE CARIBBEAN AND BEYOND VOL 14 • 2016 ISSN 0799-1401 Editor I AN B OX I LL Notions of Beauty & Sexuality in Black Communities in the Caribbean and Beyond GUEST EDITORS: Michael Barnett and Clinton Hutton IDEAZ Editor Ian Boxill Vol. 14 • 2016 ISSN 0799-1401 © 2016 by Centre for Tourism & Policy Research & Ian Boxill All rights reserved Ideaz-Institute for Intercultural and Comparative Research / Ideaz-Institut für interkulturelle und vergleichende Forschung Contact and Publisher: www.ideaz-institute.com IDEAZ–Journal Publisher: Arawak publications • Kingston, Jamaica Credits Cover photo –Courtesy of Lance Watson, photographer & Chyna Whyne, model Photos reproduced in text –Courtesy of Clinton Hutton (Figs. 2.1, 4.4, 4.5, G-1, G-2, G-5) David Barnett (Fig. 4.1) MITS, UWI (Figs. 4.2, 4.3) Lance Watson (Figs. 4.6, 4.7, G.3, G-4) Annie Paul (Figs. 6.1, 6.2, 6.3) Benjamin Asomoah (Figs. G-6, G-7) C O N T E N T S Editorial | v Acknowledgments | ix • Articles Historical Sociology of Beauty Practices: Internalized Racism, Skin Bleaching and Hair Straightening | Imani M. Tafari-Ama 1 ‘I Prefer The Fake Look’: Aesthetically Silencing and Obscuring the Presence of the Black Body | Clinton Hutton 20 Latin American Hyper-Sexualization of the Black Body: Personal Narratives of Black Female Sexuality/Beauty in Quito, Ecuador | Jean Muteba Rahier 33 The Politics of Black Hair: A Focus on Natural vs Relaxed Hair for African-Caribbean Women | Michael Barnett 69 Crossing Borders, Blurring Boundaries: -

The Genetics of Human Skin and Hair Pigmentation

GG20CH03_Pavan ARjats.cls July 31, 2019 17:4 Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics The Genetics of Human Skin and Hair Pigmentation William J. Pavan1 and Richard A. Sturm2 1Genetic Disease Research Branch, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, USA; email: [email protected] 2Dermatology Research Centre, The University of Queensland Diamantina Institute, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland 4102, Australia; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2019. 20:41–72 Keywords First published as a Review in Advance on melanocyte, melanogenesis, melanin pigmentation, skin color, hair color, May 17, 2019 genome-wide association study, GWAS The Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics is online at genom.annualreviews.org Abstract https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genom-083118- Human skin and hair color are visible traits that can vary dramatically Access provided by University of Washington on 09/02/19. For personal use only. 015230 within and across ethnic populations. The genetic makeup of these traits— Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2019.20:41-72. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Copyright © 2019 by Annual Reviews. including polymorphisms in the enzymes and signaling proteins involved in All rights reserved melanogenesis, and the vital role of ion transport mechanisms operating dur- ing the maturation and distribution of the melanosome—has provided new insights into the regulation of pigmentation. A large number of novel loci involved in the process have been recently discovered through four large- scale genome-wide association studies in Europeans, two large genetic stud- ies of skin color in Africans, one study in Latin Americans, and functional testing in animal models. -

Genetic Determinants of Skin Color, Aging, and Cancer Genetische Determinanten Van Huidskleur, Huidveroudering En Huidkanker

Genetic Determinants of Skin Color, Aging, and Cancer Genetische determinanten van huidskleur, huidveroudering en huidkanker Leonie Cornelieke Jacobs Layout and printing: Optima Grafische Communicatie, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Cover design: Annette van Driel - Kluit © Leonie Jacobs, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the author or, when appropriate, of the publishers of the publications. ISBN: 978-94-6169-708-0 Genetic Determinants of Skin Color, Aging, and Cancer Genetische determinanten van huidskleur, huidveroudering en huidkanker Proefschrift Ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van rector magnificus Prof. dr. H.A.P. Pols en volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op vrijdag 11 september 2015 om 11:30 uur door Leonie Cornelieke Jacobs geboren te Rotterdam PROMOTIECOMMISSIE Promotoren: Prof. dr. T.E.C. Nijsten Prof. dr. M. Kayser Overige leden: Prof. dr. H.A.M. Neumann Prof. dr. A.G. Uitterlinden Prof. dr. C.M. van Duijn Copromotor: dr. F. Liu COntents Chapter 1 General introduction 7 PART I SKIn COLOR Chapter 2 Perceived skin colour seems a swift, valid and reliable measurement. 29 Br J Dermatol. 2015 May 4; [Epub ahead of print]. Chapter 3 Comprehensive candidate gene study highlights UGT1A and BNC2 37 as new genes determining continuous skin color variation in Europeans. Hum Genet. 2013 Feb; 132(2): 147-58. Chapter 4 Genetics of skin color variation in Europeans: genome-wide association 59 studies with functional follow-up. -

An Ethnographic Study in Barkly East

Land as a Site of Remembrance: An Ethnographic Study in Barkly East By Karen Nortje Supervisor: Dr. R. Ebr.- Vally A THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS University of the Witwatersrand Department of Social Anthropology 2006 1 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the ways in which people in Barkly East, a small town in the Eastern Cape, attribute feelings of belonging to the land they own and work. In a country such as South Africa, where the contestation of land is prominent and so integral to the political and social discourse, questions related to the idea of belonging are necessary and important. Significant questions addressed by this thesis are: Who belongs and why do they feel they belong? More importantly, the question of who does not belong, is addressed. In Barkly East a tug of war exists between groups and individuals who want matters to remain constant and those who need the status quo to change. What stands out, moreover, in this community, is its duality on many levels of society, which is played out both consciously and unconsciously. This duality is also manifested through social, racial and economic relations, and is supported by an unequal access to land. This thesis identifies three main elements which contribute to the creation of narratives of belonging in Barkly East. Firstly, history and the perception of history create strong links between personal and communal identity, which in turn reinforces and legitimises claims of belonging. Secondly, hierarchy in terms of gender and race plays an important part in this narration, as some residents are more empowered in this process due to either their gender or race. -

2020 PRODUCT CATALOG 2 Call Sales Support at 800-325-7354 Page 04 Introduction TABLE 06 PRE-PEN® (Benzylpenicilloyl Polylysine Injection USP)

2020 PRODUCT CATALOG 2 Call Sales Support at 800-325-7354 page 04 Introduction TABLE 06 PRE-PEN® (benzylpenicilloyl polylysine injection USP) 07 Center-Al® (allergenic extract, alum precipitated) OF 08 Sublingual Immunotherapy Tablets 09 ODACTRA® CONTENTS 10 GRASTEK® 11 RAGWITEK® 12 Allergen Extracts 13 Pollen Extracts 16 Pollen Mixes 17 Molds 17 Smuts 18 Insects 18 Epidermals 19 Foods/Ingestants 21 Standardized Extracts 22 Pollen 22 Pollen Mixes 22 Epidermals 22 Mites 23 Ancillary Products 24 Normal Saline with Phenol (NSP) 24 Albumin Saline with Phenol (HSA) 24 50% Glycerin 25 Sterile Empty Vials (SEV) 26 Amber Sterile Empty Vials (SEV) 27 Non-Sterile Dropper Vials, Dropper Tips, Pumps 28 Colored Caps for Vials 28 Miscellaneous (labels, information sheets, etc.) 29 Allergy Diagnostics 29 Diagnostic Controls 29 Skin Testing Systems 30 Syringes 30 Mixing Syringes 30 Safety Syringes 30 Standard Syringes 31 Trays 32 Package Inserts 57 Fax Order Form 58 Ordering Information You are encouraged to report patient reactions to skin testing and/or immunotherapy to ALK. Our contact information is toll-free 1-855-216-6497 or email [email protected] ALK is a global allergy solutions company, with a wide range of allergy treatments, products and services that meet the unique needs of allergy sufferers, their families and healthcare professionals. ALK is committed to helping as many people with allergy as possible, which means providing your practice with quality supplies and services to help your business thrive and provide your patients with educational materials to support immunotherapy awareness and improve compliance. From our extensive selection of allergy extracts, skin testing devices, unique products, and patient resources, we are committed to helping you improve the lives of more allergic patients. -

The “Pop Pacific” Japanese-American Sojourners and the Development of Japanese Popular Music

The “Pop Pacific” Japanese-American Sojourners and the Development of Japanese Popular Music By Jayson Makoto Chun The year 2013 proved a record-setting year in Japanese popular music. The male idol group Arashi occupied the spot for the top-selling album for the fourth year in a row, matching the record set by female singer Utada Hikaru. Arashi, managed by Johnny & Associates, a talent management agency specializing in male idol groups, also occupied the top spot for artist total sales while seven of the top twenty-five singles (and twenty of the top fifty) that year also came from Johnny & Associates groups (Oricon 2013b).1 With Japan as the world’s second largest music market at US$3.01 billion in sales in 2013, trailing only the United States (RIAJ 2014), this talent management agency has been one of the most profitable in the world. Across several decades, Johnny Hiromu Kitagawa (born 1931), the brains behind this agency, produced more than 232 chart-topping singles from forty acts and 8,419 concerts (between 2010 and 2012), the most by any individual in history, according to Guinness World Records, which presented two awards to Kitagawa in 2010 (Schwartz 2013), and a third award for the most number-one acts (thirty-five) produced by an individual (Guinness World Record News 2012). Beginning with the debut album of his first group, Johnnys in 1964, Kitagawa has presided over a hit-making factory. One should also look at R&B (Rhythm and Blues) singer Utada Hikaru (born 1983), whose record of four number one albums of the year Arashi matched.