Where Was the Outrage? the Lack of Public Concern for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

2 a Quotation of Normality – the Family Myth 3 'C'mon Mum, Monday

Notes 2 A Quotation of Normality – The Family Myth 1 . A less obvious antecedent that The Simpsons benefitted directly and indirectly from was Hanna-Barbera’s Wait ‘til Your Father Gets Home (NBC 1972–1974). This was an attempt to exploit the ratings successes of Norman Lear’s stable of grittier 1970s’ US sitcoms, but as a stepping stone it is entirely noteworthy through its prioritisation of the suburban narrative over the fantastical (i.e., shows like The Flintstones , The Jetsons et al.). 2 . Nelvana was renowned for producing well-regarded production-line chil- dren’s animation throughout the 1980s. It was extended from the 1960s studio Laff-Arts, and formed in 1971 by Michael Hirsh, Patrick Loubert and Clive Smith. Its success was built on a portfolio of highly commercial TV animated work that did not conform to a ‘house-style’ and allowed for more creative practice in television and feature projects (Mazurkewich, 1999, pp. 104–115). 3 . The NBC US version recast Feeble with the voice of The Simpsons regular Hank Azaria, and the emphasis shifted to an American living in England. The show was pulled off the schedules after only three episodes for failing to connect with audiences (Bermam, 1999, para 3). 4 . Aardman’s Lab Animals (2002), planned originally for ITV, sought to make an ironic juxtaposition between the mistreatment of animals as material for scientific experiment and the direct commentary from the animals them- selves, which defines the show. It was quickly assessed as unsuitable for the family slot that it was intended for (Lane, 2003 p. -

Spike: the Devil You Know Free

FREE SPIKE: THE DEVIL YOU KNOW PDF Franco Urru,Chris Cross,Bill Williams | 104 pages | 04 Jan 2011 | Idea & Design Works | 9781600107641 | English | San Diego, United States Spike: The Devil You Know - Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel Wiki Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to Spike: The Devil You Know. Want Spike: The Devil You Know Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Spike by Bill Williams. Chris Cross. While out and about drinking, naturally Spike gets in trouble over a girl of course and finds himself in the middle of a conspiracy that involves Hellmouths, blood factories, and demons. Just another day in Los Angeles, really. But when devil Eddie Hope gets involved, they might just kill each other before getting to the bad guys! Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Other Editions 3. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Spikeplease sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. The mini series sees a new character Eddie Hope stumble into Buffyverse alumni, Spike! I enjoyed their conversations but the general story was sort of Then again, that is the Buffyverse way of handling things! Jan 30, Sesana rated it it was ok Shelves: comicsfantasy. Well, that was pointless. The story is dull enough that I doubt the writer was interested in it. -

A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected]

Student Research and Creative Works Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2015 The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/6 Krista Silva The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works I am an inhabitant of the Whedonverse. When I say this, I don’t just mean that I am a fan of Joss Whedon. I am sincere. I live and breathe his works, the ever-expanding universe— sometimes funny, sometimes scary, and often heartbreaking—that he has created. A multi- talented writer, director and creator, Joss is responsible for television series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer , Firefly , Angel , and Dollhouse . In 2012 he collaborated with Drew Goddard, writer for Buffy and Angel , to bring us the satirical horror film The Cabin in the Woods . Most recently he has been integrated into the Marvel cinematic universe as the director of The Avengers franchise, as well as earning a creative credit for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. My love for Joss Whedon began in 1998. I was only eleven years old, and through an incredible moment of happenstance, and a bit of boredom, I turned the television channel to the WB and encountered my first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer . I was instantly smitten with Buffy Summers. She defied the rules and regulations of my conservative southern upbringing. -

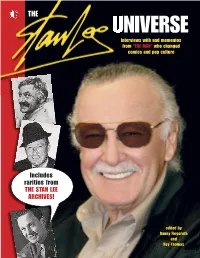

Includes Rarities from the STAN LEE ARCHIVES!

THE UNIVERSE Interviews with and mementos from “THE MAN” who changed comics and pop culture Includes rarities from THE STAN LEE ARCHIVES! edited by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas CONTENTS About the material that makes up THE STAN LEE UNIVERSE Some of this book’s contents originally appeared in TwoMorrows’ Write Now! #18 and Alter Ego #74, as well as various other sources. This material has been redesigned and much of it is accompanied by different illustrations than when it first appeared. Some material is from Roy Thomas’s personal archives. Some was created especially for this book. Approximately one-third of the material in the SLU was found by Danny Fingeroth in June 2010 at the Stan Lee Collection (aka “ The Stan Lee Archives ”) of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, and is material that has rarely, if ever, been seen by the general public. The transcriptions—done especially for this book—of audiotapes of 1960s radio programs featuring Stan with other notable personalities, should be of special interest to fans and scholars alike. INTRODUCTION A COMEBACK FOR COMIC BOOKS by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas, editors ..................................5 1966 MidWest Magazine article by Roger Ebert ............71 CUB SCOUTS STRIP RATES EAGLE AWARD LEGEND MEETS LEGEND 1957 interview with Stan Lee and Joe Maneely, Stan interviewed in 1969 by Jud Hurd of from Editor & Publisher magazine, by James L. Collings ................7 Cartoonist PROfiles magazine ............................................................77 -

Ulating the American Man: Fear and Masculinity in the Post-9/11 American Superhero Film

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2011 Remas(k)ulating the American Man: Fear and Masculinity in the Post-9/11 American Superhero Film Carolyn P. Fisher College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Fisher, Carolyn P., "Remas(k)ulating the American Man: Fear and Masculinity in the Post-9/11 American Superhero Film" (2011). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 402. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/402 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Remas(k)ulating the American Man: Fear and Masculinity in the Post-9/11 American Superhero Film by Carolyn Fisher A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy from The College of William and Mary Accepted for _________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ______________________________________ Dr. Colleen Kennedy, Director ______________________________________ Dr. Frederick Corney ______________________________________ Dr. Arthur Knight Williamsburg, VA April 15, 2011 Fisher 1 Introduction Superheroes have served as sites for the reflection and shaping of American ideals and fears since they first appeared in comic book form in the 1930s. As popular icons which are meant to engage the American imagination and fulfill (however unrealistically) real American desires, they are able to inhabit an idealized and fantastical space in which these desires can be achieved and American enemies can be conquered. -

Little White Booklet

Narcotics Anonymous® Anglicized 1 Foreword This booklet is an introduction to the Fellowship of Narcotics Anonymous. It is written for those men and women who, like ourselves, suffer from a seemingly hopeless addiction to drugs. There is no cure for addiction, but recovery is possible by a programme of simple spiritual principles. This booklet is not meant to be comprehensive, but it contains the essentials that in our personal and group experience we know to be necessary for recovery. Serenity Prayer God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference. Who is an addict? Most of us do not have to think twice about this question. We know! Our whole life and thinking was centred in drugs in one form or another – the getting and using and finding ways and means to get more. We lived to use and used to live. Very simply, an addict is a man or woman whose life is controlled by drugs. We are people in the grip of a continuing and progressive illness whose ends are always the same: jails, institutions, and death. 2 Narcotics Anonymous 3 What is the experience that those who keep coming to our meetings Narcotics Anonymous programme? regularly stay clean. NA is a non-profit fellowship or society of men and Why are we here? women for whom drugs had become a major problem. Before coming to the Fellowship of NA, we could not We are recovering addicts who meet regularly to help manage our own lives. -

Comic Hunter

Comic Hunter - Dark Horse - 2021-09-16 Publisher Imprint Title Number Ext Edition Price Grade Important Format Dark Horse Comics 1001 Nights of Bacchus (1993) 1 5,00 $ Comic Dark Horse Comics 13th Son (2004) 1 4,00 $ Comic Dark Horse Comics 13th Son (2004) 2 4,00 $ Comic Dark Horse Comics 13th Son (2004) 3 4,00 $ Comic Dark Horse Comics 13th Son (2004) 4 4,00 $ Comic Dark Horse Comicsoriginals 3 Story Secret Files of the Giant Man 1 4,00 $ comic Dark Horse Comics 300 (1998) 2 10,00 $ Comic Dark Horse Comics 300 (1998) 3 10,00 $ Comic Dark Horse Comics 47 Ronin (2012) 2 5,00 $ Comic Dark Horse Comics Abe Sapien (2013) 1 A 10,00 $ Abe Sapien #11 Comic Dark Horse Comics Abe Sapien (2013) 2 5,00 $ Abe Sapien #12 Comic Dark Horse Comics Abe Sapien (2013) 3 5,00 $ Abe Sapien #13 Comic Dark Horse Comics Abe Sapien (2013) 4 A Max Fiumara Cover 5,00 $ Abe Sapien #14 Comic Dark Horse Comics Abe Sapien (2013) 4 B Seb Fiumara 7,00 $ Abe Sapien #14 Comic Dark Horse Comics Abe Sapien (2013) 5 5,00 $ Abe Sapien #15 Comic Dark Horse Comics Abe Sapien (2013) 6 4,00 $ Abe Sapien #16 Comic Dark Horse Comics Abe Sapien (2013) 7 5,00 $ Abe Sapien #17 Comic Dark Horse Comics Abe Sapien (2013) 8 A Max Fiumara Cover 5,00 $ Abe Sapien #18 Comic Dark Horse Comics Abe Sapien (2013) 9 A Max Fiumara Cover 4,00 $ Abe Sapien #19 Comic Dark Horse Comics Abe Sapien (2013) 10 5,00 $ Abe Sapien #20 Comic Dark Horse Comics Abe Sapien (2013) 11 4,00 $ Abe Sapien #21 Comic Dark Horse Comics Abe Sapien (2013) 12 4,00 $ Abe Sapien #22 Comic Dark Horse Comics Abe Sapien (2013) -

LCSH Section J

J (Computer program language) J. I. Case tractors Thurmond Dam (S.C.) BT Object-oriented programming languages USE Case tractors BT Dams—South Carolina J (Locomotive) (Not Subd Geog) J.J. Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) J. Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) BT Locomotives USE Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) UF Clark Hill Lake (Ga. and S.C.) [Former J & R Landfill (Ill.) J.J. "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) heading] UF J and R Landfill (Ill.) UF "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clark Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) J&R Landfill (Ill.) Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clarks Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) BT Sanitary landfills—Illinois BT Public buildings—Texas Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) J. & W. Seligman and Company Building (New York, J. James Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) BT Lakes—Georgia USE Banca Commerciale Italiana Building (New UF Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Lakes—South Carolina York, N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) Reservoirs—Georgia J 29 (Jet fighter plane) BT Public buildings—Nebraska Reservoirs—South Carolina USE Saab 29 (Jet fighter plane) J. Kenneth Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) J.T. Berry Site (Mass.) J.A. Ranch (Tex.) UF Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) UF Berry Site (Mass.) BT Ranches—Texas BT Post office buildings—Virginia BT Massachusetts—Antiquities J. Alfred Prufrock (Fictitious character) J.L. Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, N.C.) J.T. Nickel Family Nature and Wildlife Preserve (Okla.) USE Prufrock, J. Alfred (Fictitious character) UF Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, UF J.T. -

Abstract Representing the Trauma of 9/11 in U.S. Fiction

ABSTRACT REPRESENTING THE TRAUMA OF 9/11 IN U.S. FICTION: JONATHAN SAFRAN FOER, DON DELILLO AND JESS WALTER by Bryan M. Santin This thesis explores the relationship between literary narratives and a more popular mythological American narrative that constructs the 9/11 attacks as a base for cultural regeneration, heroism, or redemption. Popular 9/11 narratives tend to offer a mythic foundation for militant belligerency masked as patriotic heroism and a deeply embedded notion of “regeneration through violence” outlined by Richard Slotkin. I contrast these popular narratives with novels by Jonathan Safran Foer (Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close), Don DeLillo (Falling Man) and Jess Walter (The Zero) that stress the complexity of trauma‟s aftermath. The political and ethical value of these literary representations of trauma present nuanced characterological templates for acting-out and working through, which advocate critical self-recognition of post-9/11 American ideology and an emergence from political solipsism. REPRESENTING THE TRAUMA OF 9/11 IN U.S. FICTION: JONATHAN SAFRAN FOER, DON DELILLO AND JESS WALTER A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Bryan M. Santin Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2011 Advisor___________________________ Tim Melley Reader____________________________ Madelyn Detloff Reader___________________________ Martha Schoolman Table of Contents Introduction: 9/11 as Traumatic (Re)Introduction to the Real .................................................1 -

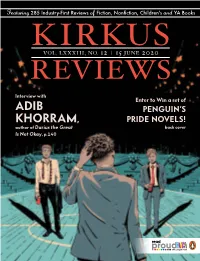

Kirkus Reviews

Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS Interview with Enter to Win a set of ADIB PENGUIN’S KHORRAM, PRIDE NOVELS! author of Darius the Great back cover Is Not Okay, p.140 with penguin critically acclaimed lgbtq+ reads! 9780142425763; $10.99 9780142422939; $10.99 9780803741072; $17.99 “An empowering, timely “A narrative H“An empowering, timely story with the power to experience readers won’t story with the power to help readers.” soon forget.” help readers.” —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews, starred review A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION WINNER OF THE STONEWALL A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION BOOK AWARD WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL 9780147511478; $9.99 9780425287200; $22.99 9780525517511; $8.99 H“Enlightening, inspiring, “Read to remember, “A realistic tale of coming and moving.” remember to fight, fight to terms and coming- —Kirkus Reviews, starred review together.” of-age… with a touch of —Kirkus Reviews magic and humor” A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION —Kirkus Reviews Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s,and YA Books. KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS THE PRIDEISSUE Books that explore the LGBTQ+ experience Interviews with Meryl Wilsner, Meredith Talusan, Lexie Bean, MariNaomi, L.C. Rosen, and more from the editor’s desk: Our Books, Ourselves Chairman HERBERT SIMON BY TOM BEER President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # As a teenager, I stumbled across a paperback copy of A Boy’s Own Story Chief Executive Officer on a bookstore shelf. Edmund White’s 1982 novel, based loosely on his MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] coming-of-age, was already on its way to becoming a gay classic—but I Editor-in-Chief didn’t know it at the time.