Stereoisograms of Octahedral Complexes. I. Chirality and RS-Stereogenicity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Organic Chemistry 2018 More

Introduction to Organic Chemistry 25 Introduction to Organic Chemistry Handout 2 - Stereochemistry OH O O OH enantiomers Me OH HO Me A B NH2 NH2 diastereomers diastereomers diastereomers OH O O OH Me OH HO Me C D NH2 enantiomers NH2 http://burton.chem.ox.ac.uk/teaching.html ◼ Organic Chemistry J. Clayden, N. Greeves, S. Warren ◼ Stereochemistry at a Glance J. Eames & J. M. Peach ◼ The majority of organic chemistry text books have good chapters on the topics covered by these lectures ◼ Eliel Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds (advanced reference text) Introduction to Organic Chemistry 26 ◼ representations of formulae in organic chemistry ◼ skeletal representations are far less cluttered and as a result are much clearer than drawing all carbon and hydrogen atoms explicitly, they also give a much better representation of the likely bond angles and hence hybridisation states of the carbon atoms ◼ skeletal representations allow functional groups (sites of reactivity) to be clearly seen ◼ guidelines for drawing skeletal structures i) draw chains of atoms as zig-zags ii) do not draw C atoms unless there is good reason to draw them iii) do not draw C-H bonds unless there is good reason to draw then iv) do not draw Hs attached to carbon atoms unless there is good reason to draw them v) make drawings realistic Introduction to Organic Chemistry 27 ◼ representing structures in three dimensions ◼ a wedged bond indicates the bond is projecting out in front of the plane of the paper ◼ a dashed bond indicates the bond is projecting behind the plane -

Teaching with SCIGRESS

Teaching with SCIGRESS Exercises on Molecular Modeling in Chemistry Crispin Wong and James Currie, eds. Pacific University Teaching with SCIGRES Molecular Modeling in Chemistry Crispin Wong and James Currie Editors Pacific University Forest Grove, Oregon 2 Copyright statement © 2001 - 2012 Fujitsu Limited. All rights reserved. This document may not be used, sold, transferred, copied or reproduced, in any manner or form, or in any medium, to any person other than with the prior written consent of Fujitsu Limited. Published by Fujitsu Limited. All possible care has been taken in the preparation of this publication. Fujitsu Limited does not accept liability for any inaccuracies that may be found. Fujitsu Limited reserves the right to make changes without notice both to this publication and to the product it describes. 3 Table of Contents Exercises 7 Part 1: General Chemistry Experiment 1 Calculating the Geometry of Molecules and Ions 16 Experiment 2 Kinetics of Substitution Reactions 29 Experiment 3 Sunscreen and Ultraviolet Absorption 38 Part 2: Organic Chemistry Experiment 4 Evaluations of Conformations of Menthone and Isomenthone 46 Experiment 5 The Evelyn Effect 52 Part 3: Physical Chemistry Experiment 6 Investigating the Resonance Stabilization of Benzene 63 Experiment 7 Investigation of the Rotational Barrier in N-N-dimethylacetamide 68 Part 4: Inorganic Chemistry Experiment 8 Polarities of Small Molecules 75 Experiment 9 Structures of Molecules Which Exceed the Octet Rule. 77 Experiment 10 Comparison of Gas Phase Acidities of Binary -

Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry. IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Division VIII Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Division Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry. IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. Prepared for publication by Henri A. Favre and Warren H. Powell, Royal Society of Chemistry, ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4 Chapter P-9 SPECIFICATION OF CONFIGURATION AND CONFORMATION P-90 Introduction P-91 Stereoisomer graphical representation and naming P-92 The Cahn-Ingold-Prelog (CIP) priority system and the Sequence Rules P-93 Configuration specification P-94 Conformation and conformational stereodescriptors P-90 INTRODUCTION This Chapter is concerned only with the main principles for specification of configuration and conformation of organic compounds. The structure of an organic compound is systematically indicated by one or more affixes added to a name that does not itself prescribe stereochemical configuration or conformation; such affixes are generally called ‘stereodescriptors’. Thus, stereoisomers, such as enantiomers, have names that differ only in the stereodescriptors used. In contrast, ‘cis/trans’ isomers may have different names because of different stereodescriptors or names differing in the type of nomenclature. Also, certain retained names imply their own stereochemical description, for example, maleic acid, cholesterol, and other natural products described in Chapter P-10. In order to arrive at an unambiguous description of stereoisomers, Cahn, Ingold, and Prelog (refs. 34, 35) recommended an order of seniority for the ligands (atoms and groups) attached to carbon and other atoms, which is commonly called the ‘CIP priority system’. The priority is established by the application of ‘Sequence Rules’. These rules are discussed in P-92. Their application is then described for stereogenic units, mainly for the most usual compounds encountered in organic chemistry. -

Modular Chemical Descriptor Language (MCDL): Stereochemical Modules Andrei a Gakh1*, Michael N Burnett1, Sergei V Trepalin2, Alexander V Yarkov2

Gakh et al. Journal of Cheminformatics 2011, 3:5 http://www.jcheminf.com/content/3/1/5 METHODOLOGY Open Access Modular Chemical Descriptor Language (MCDL): Stereochemical modules Andrei A Gakh1*, Michael N Burnett1, Sergei V Trepalin2, Alexander V Yarkov2 Abstract Background: In our previous papers we introduced the Modular Chemical Descriptor Language (MCDL) for providing a linear representation of chemical information. A subsequent development was the MCDL Java Chemical Structure Editor which is capable of drawing chemical structures from linear representations and generating MCDL descriptors from structures. Results: In this paper we present MCDL modules and accompanying software that incorporate unique representation of molecular stereochemistry based on Cahn-Ingold-Prelog and Fischer ideas in constructing stereoisomer descriptors. The paper also contains additional discussions regarding canonical representation of stereochemical isomers, and brief algorithm descriptions of the open source LINDES, Java applet, and Open Babel MCDL processing module software packages. Conclusions: Testing of the upgraded MCDL Java Chemical Structure Editor on compounds taken from several large and diverse chemical databases demonstrated satisfactory performance for storage and processing of stereochemical information in MCDL format. Background Java applet to be capable of restoring these coordinates In our previous paper we introduced the Modular Che- to draw a structure. As a result, the current applet algo- mical Descriptor Language (MCDL) for providing a lin- rithm that was developed to process MCDL descriptors ear representation of structural and other chemical can also be used for processing of other coordinate-less information [1]. All MCDL descriptors have two unique structure representations, such as SMILES [3,4] and modules that describe the composition and the connec- InChI [5]. -

IR-9 Coordination Compounds (Draft March 2004)

1 IR-9 Coordination Compounds (Draft March 2004) CONTENTS IR-9.1 Introduction IR-9.1.1 General IR-9.1.2 Definitions IR-9.1.2.1 Background IR-9.1.2.2 Coordination compounds and the coordination entity IR-9.1.2.3 Central atom IR-9.1.2.4 Ligands IR-9.1.2.5 Coordination polyhedron IR-9.1.2.6 Coordination number IR-9.1.2.7 Chelation IR-9.1.2.8 Oxidation state IR-9.1.2.9 Coordination nomenclature: an additive nomenclature IR-9.1.2.10 Bridging ligands IR-9.1.2.11 Metal-metal bonds IR-9.2 Describing the constitution of coordination compounds IR-9.2.1 General IR-9.2.2 Naming coordination compounds IR-9.2.2.1 Sequences of ligands and central atoms within names IR-9.2.2.2 Number of ligands in a coordination entity IR-9.2.2.3 Representing ligands in names IR-9.2.2.4 Charge numbers, oxidation numbers, and ionic proportions IR-9.2.3 Formulae of coordination compounds IR-9.2.3.1 Sequence of symbols within the coordination formula IR-9.2.3.2 Use of enclosing marks IR-9.2.3.3 Ionic charges and oxidation numbers IR-9.2.3.4 Use of abbreviations IR-9.2.4 Specifying donor atoms IR-9.2.4.1 General IUPAC ProvisionalIR-9.2.4.2 The kappa convention Recommendations IR-9.2.4.3 Comparison of the eta and kappa nomenclatures Page 1 of 69 DRAFT 2 April 2004 2 IR-9.2.4.4 Donor atom symbol to indicate points of ligation IR-9.2.5 Polynuclear complexes IR-9.2.5.1 General IR-9.2.5.2 Bridging ligands IR-9.2.5.3 Metal-metal bonding IR-9.2.5.4 Symmetrical dinuclear entities IR-9.2.5.5 Unsymmetrical dinuclear entities IR-9.2.5.6 Trinuclear and larger structures IR-9.2.5.7 Polynuclear -

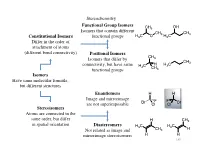

Isomer Overview the Following Table Summarizes the Various Types Of

Chem 201/Beauchamp Topic 7, Stereochemistry 1 Isomer Overview The following table summarizes the various types of isomers we will encounter as we proceed through organic chemistry. Isomers - compounds that have the same formula Constitutional or structural Stereoisomers have their atoms isomers have their atoms attached with the same connectivity, joined together in different but differ in their arrangements in arrangements space chain or skeletal positional functional isomers isomers group isomers Cl O OH butane 1-chloropropane Cl H propanal prop-2-en-1-ol (aldehyde) (allyl alcohol) O O 2-methylpropane 2-chloropropane oxatane propanone (cyclic ether) (ketone) Conformational isomers Enantiomers are mirror Diastereomers are differ by rotation about a image reflections that stereoisomers that single bond and are usually are not superimposable are not mirror images easily interconverted. (different). of one another. CH a. 3 CH3 CH3 OH OH fast H C OH H C OH HO C H fast C C vs. CH3CH2 H2CH3C H H H C OH H C OH HO C H H3C CH3 CH 3 CH3 CH3 CH3 CH H H 3 meso (dl) enantiomers b. fast H CH3 CH3 H E or trans Z or cis (dl) or () enantiomer pairs also called H CH H H 3 geometric isomers and cis/trans isomers CH3 CH3 CH3 H cis trans Chem 201/Beauchamp Topic 7, Stereochemistry 2 Essential Vocabulary of Stereochemistry – terms to know for this topic Chiral center – a tetrahedral atom with four different groups attached, a single chiral center is not superimposable on its mirror image, also called a stereogenic center, and asymmetric center Stereogenic center – any center where interchange of two groups produces stereoisomers (different structures), could be a chiral center producing R/S differences, or an alkene producing E/Z differences or cis/trans in a ring Absolute configuration (R and S) – the specific 3 dimensional configuration about a tetrahedral shape, determined by assigning priorities (1-4) based on the highest atomic number of an atom at the first point of difference. -

An Introduction to Molecular Symmetry

Chapter 3 An introduction to molecular symmetry TOPICS & Symmetry operators and symmetry elements & Point groups & An introduction to character tables & Infrared spectroscopy & Chiral molecules the resulting structure is indistinguishable from the first; 3.1 Introduction another 1208 rotation results in a third indistinguishable molecular orientation (Figure 3.1). This is not true if we Within chemistry, symmetry is important both at a molecu- carry out the same rotational operations on BF2H. lar level and within crystalline systems, and an understand- Group theory is the mathematical treatment of symmetry. ing of symmetry is essential in discussions of molecular In this chapter, we introduce the fundamental language of spectroscopy and calculations of molecular properties. A dis- group theory (symmetry operator, symmetry element, point cussion of crystal symmetry is not appropriate in this book, group and character table). The chapter does not set out to and we introduce only molecular symmetry. For qualitative give a comprehensive survey of molecular symmetry, but purposes, it is sufficient to refer to the shape of a molecule rather to introduce some common terminology and its using terms such as tetrahedral, octahedral or square meaning. We include in this chapter an introduction to the planar. However, the common use of these descriptors is vibrational spectra of simple inorganic molecules, with an not always precise, e.g. consider the structures of BF3, 3.1, emphasis on using this technique to distinguish between pos- and BF2H, 3.2, both of which are planar. A molecule of sible structures for XY2,XY3 and XY4 molecules. Complete BF3 is correctly described as being trigonal planar, since its normal coordinate analysis of such species is beyond the symmetry properties are fully consistent with this descrip- remit of this book. -

Stereochemistry

Lecture note- 2 Organic Chemistry CHE 502 STEREOCHEMISTRY DEPARTMENT OF CHEMISTRY UTTARAKHAND OPEN UNIVERSITY UNIT 4: STEREOCHEMISTRY 1 CONTENTS 4.1 Objectives 4.2 Introduction 4.3 Isomerism 4.4 Structural (Constitutional) Isomerism 4.5 Stereo (Configurational) isomerism 4.5.1 Geometrical Isomerism 4.5.2 Optical Isomerism 4.6 Element of Symmetry 4.7 Stereogenic centre (Stereogenicity) 4.7.1 Optical activity and Enantiomerism 4.7.2 Properties of enantiomerism 4.7.3 Chiral and achiral molecules with two stereogenic centers 4.7.4 Diastereomers 4.7.5 Properties of Diastereomers 4.7.6 Erythro (syn) Threo (anti) diastereomers 4.7.7 Meso compounds 4.8 Relative and absolute configurations 4.8.1 D/L nomenclature 4.8.2 R/S nomenclature 4.8.3 Sequence Rule 4.9 Newman and sawhorse projection formulae 4.10 Fisher flying and wedge formulae 4.11 Racemic mixture (racemates) 4.12 Quasi enantiomers 4.13 Quasi racemates 4.14 Stereochemistry of allenes, spiranes, biphenyls, ansa compounds, cyclophanes and related compounds 4.15 Summary 4.16 Terminal Questions 4.17 Answers 4.1 OBJECTIVES In this unit learner will be able to: ➢ Depict various types of isomerism exhibited by organic compounds and their representation ➢ Analyze the three dimensional depictions of organic compounds and their two dimensional representations. ➢ Learn Stereogenicity, chirality, enantiomerism, diastereomerism, their relative and absolute configurations ➢ Learn about the various stereo chemical descriptors such as (cis-trans, E/Z, D/L, d/l, erythro/threo, R/S and syn/anti) given to organic molecules differ ➢ Describe the stereochemistry of various rigid and complex molecules like spiranes, adamentanes, catenanes, cyclophanes etc. -

Advances in Gold-Carbon Bond Formation: Mono-, Di-, and Triaurated Organometallics

ADVANCES IN GOLD-CARBON BOND FORMATION: MONO-, DI-, AND TRIAURATED ORGANOMETALLICS By JAMES E. HECKLER Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Thesis Advisor: Dr. Thomas G. Gray Department of Chemistry CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY January 2016 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of ____________________________________________________James E. Heckler candidate for the _____________________________Doctor of Philosophy degree*. Carlos E. Crespo-Hernandez (Signed) __________________________________ (chair of the committee) Anthony J. Pearson __________________________________ __________________________________Genevieve Sauve __________________________________Horst von Recum __________________________________Thomas G. Gray (date) ____________________27 July 2015 * We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Dedication To my family and best friends i Table of Contents List of Tables …………………………………………………………………………………….iii List of Figures ……………..………………………………………………………………….......v List of Schemes and Charts..…………………………………………………………………..…..x Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………………….……..xii List of Symbols and Abbreviations ……………………………………………………….....…xiii Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………………..…..xxi Chapter 1. General Introduction ………………….......................................................1 1.1 Fundamental gold chemistry………………………………………………1 1.1.1 Relativistic effects -

Isomers Have Same Molecular Formula, but Different Structures Constitutional Isomers Differ in the Order of Attachment

Stereochemistry Functional Group Isomers CH3 OH Isomers that contain different CH3 CH3 Constitutional Isomers functional groups H3C O H3C Differ in the order of attachment of atoms (different bond connectivity) Positional Isomers CH Isomers that differ by 3 CH3 connectivity, but have same H C H H3C 3 CH functional groups 3 Isomers Have same molecular formula, but different structures Enantiomers H H Image and mirrorimage Br F F Br are not superimposable Cl Cl Stereoisomers Atoms are connected in the same order, but differ H CH3 in spatial orientation Diastereomers H3C H3C Not related as image and CH3 H mirrorimage stereoisomers H H 140 Stereochemistry The types of stereoisomers can in fact be further delineated 1) Conformational Two different conformers of the same compound may have nonsuperimposable mirror images Cl Br The two conformers can be H If the energy of interconversion is interconverted by a bond rotation H H low (< ~20-25 kcal/mol) the two H conformers cannot be separated and thus not considered chiral Br Br H Cl Cl H H H H H H H CO2H HO2C Can also observe with conformational HO2C CO2H enantiomers if the energy to interconvert is O2N NO2 too high NO2 O2N 141 Stereochemistry 2) Configurational Typically when an organic chemist refers to stereoisomers, they generally mean configurational stereoisomers where the two isomers can only be interconverted by breaking a covalent bond (cannot be made equivalent by rotation about any bond) A chiral compound can Enantiomers Br Br have only 1 enantiomer, Nonsuperimposable mirror H H but -

Controlled Synthesis of Topologically Templated

CONTROLLED SYNTHESIS OF TOPOLOGICALLY TEMPLATED CATENANE AND KNOTTY POLYMER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Chemistry University of Houston In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Ajaykumar Bunha May 2013 CONTROLLED SYNTHESIS OF TOPOLOGICALLY TEMPLATED CATENANE AND KNOTTY POLYMER Ajaykumar Bunha APPROVED: Dr. Randolph P. Thummel, Chairman Dr. Rigoberto C. Advincula Dr. Ognjen S. Miljanic Dr. Roman S. Czernuszewicz Dr. Megan L. Robertson Dr. Dan E. Wells, Dean College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to all of those with whom I have had the pleasure to work with during my entire time in graduate school. To my committee members, Dr. Thummel, Dr. Miljanic, Dr. Czernuszewicz, and Dr. Robertson, for their encouraging words, thoughtful criticism, time and attention. To Dr. Rigoberto Advincula, who gave me the opportunity to learn and for his guidance. To the past member of the Advincula group Rams, Guoqian, Cel, Jane, Roderick, Nicel, Ed, Allan, Katie, Subbu, Deepali, and Kim for their support; to the present members Joey, Pengfei, Kat, Al, and Brylee for participating in my learning experience. To my parents and other family members for all their guidances. To my dear wife Megha for her love, support, and patience. iii CONTROLLED SYNTHESIS OF TOPOLOGICALLY TEMPLATED CATENANE AND KNOTTY POLYMER An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Chemistry University of Houston In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Ajaykumar Bunha May 2013 iv ABSTRACT The topologically interesting structure of polymer catenanes and knotty polymers are of high interest for their unique chemical and physical properties. -

The Role of Stochastic Models in Interpreting the Origins of Biological Chirality

Symmetry 2010, 2, 767-798: doi:10.3390/sym2020767 OPEN ACCESS symmetry ISSN 2073-8994 www.mdpi.com/journal/symmetry Review The Role of Stochastic Models in Interpreting the Origins of Biological Chirality Gábor Lente Department of Inorganic and Analytical Chemistry, University of Debrecen, P.O.B. 21, Debrecen, H-4010 Hungary; E-Mail: [email protected] Received: 1 March 2010; in revised form: 29 March 2010; / Accepted: 6 April 2010 / Published: 12 April 2010 Abstract: This review summarizes recent stochastic modeling efforts in the theoretical research aimed at interpreting the origins of biological chirality. Stochastic kinetic models, especially those based on the continuous time discrete state approach, have great potential in modeling absolute asymmetric reactions, experimental examples of which have been reported in the past decade. An overview of the relevant mathematical background is given and several examples are presented to show how the significant numerical problems characteristic of the use of stochastic models can be overcome by non-trivial, but elementary algebra. In these stochastic models, a particulate view of matter is used rather than the concentration-based view of traditional chemical kinetics using continuous functions to describe the properties system. This has the advantage of giving adequate description of single-molecule events, which were probably important in the origin of biological chirality. The presented models can interpret and predict the random distribution of enantiomeric excess among repetitive experiments, which is the most striking feature of absolute asymmetric reactions. It is argued that the use of the stochastic kinetic approach should be much more widespread in the relevant literature.