Handout VIII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

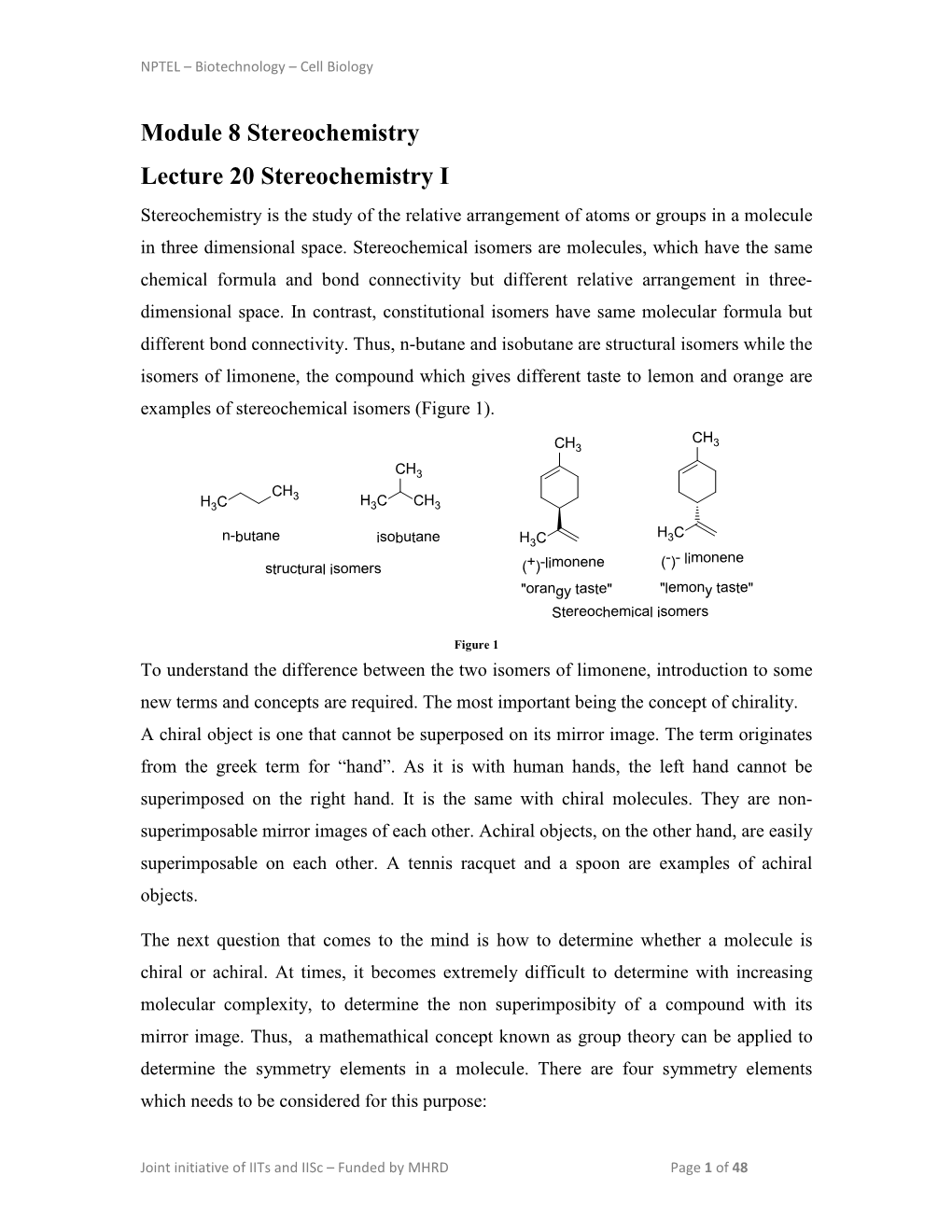

Recommended publications

-

A Practical Approach to Chiral Separations by Liquid Chromatography

A Practical Approach to Chiral Separations by Liquid Chromatography Edited by G. Subramanian Weinheim • New York VCH Basel • Cambridge • Tokyo Contents 1 An Introduction to Enantioseparation by Liquid Chromatography Charles A. White and Ganapathy Subramanian 1.1 Introduction 1 1.1.1 What is Chirality? 1 1.1.2 What Causes Chirality? 2 1.1.3 Why is Chirality Important? 4 1.2 Industries which Require Enantioseparations 4 1.2.1 Pharmaceutical Industry 4 1.2.2 Agrochemical Industry 5 1.2.3 Food and Drink Industry 6 1.2.4 Petrochemical Industry 6 1.3 Chiral Liquid Chromatography 7 1.3.1 Type I Chiral Phases 8 1.3.2 Type II Chiral Stationary Phases 10 1.3.3 Type III Chiral Stationary Phases 10 1.3.3.1 Microcrystalline Cellulose Triacetate and Tribenzoate 10 1.3.3.2 Cyclodextrins 11 1.3.3.3 Crown Ethers 11 1.3.3.4 Synthetic Polymers •. 12 1.3.4 Type IV Chiral Stationary Phases 13 1.3.5 Type V Chiral Stationary Phases 13 1.3.6 Mobile Phase Additives 14 1.3.6.1 Metal Complexes 14 1.3.6.2 Ion-pair Formation 15 1.3.6.3 Uncharged Chiral Additives 15 1.4 The Future 16 2 Modeling Enantiodifferentiation in Chiral Chromatography Kenny B. Lipkowitz 2.1 Introduction 19 2.2 Modeling 19 # VIII Contents 2.3 Computational Tools 22 2.3.1 Quantum Mechanics 22 2.3.2 Molecular Mechanics 23 2.3.3 Molecular Dynamics 24 2.3.4 Monte Carlo Simulations 24 2.3.5 Graphics 25 2.4 Modeling Enantioselective Binding in Chromatography 26 2.4.1 Type I CSPs 26* 2.4.2 Type II CSPs 41 2.4.3 Type III CSPs 44 2.5 Related Studies 49 2.6 Summary 50 3 Regulatory Implications and Chiral Separations Jeffrey R. -

Compact Hyperbolic Tetrahedra with Non-Obtuse Dihedral Angles

Compact hyperbolic tetrahedra with non-obtuse dihedral angles Roland K. W. Roeder ∗ January 7, 2006 Abstract Given a combinatorial description C of a polyhedron having E edges, the space of dihedral angles of all compact hyperbolic polyhe- dra that realize C is generally not a convex subset of RE [9]. If C has five or more faces, Andreev’s Theorem states that the correspond- ing space of dihedral angles AC obtained by restricting to non-obtuse angles is a convex polytope. In this paper we explain why Andreev did not consider tetrahedra, the only polyhedra having fewer than five faces, by demonstrating that the space of dihedral angles of com- pact hyperbolic tetrahedra, after restricting to non-obtuse angles, is non-convex. Our proof provides a simple example of the “method of continuity”, the technique used in classification theorems on polyhe- dra by Alexandrow [4], Andreev [5], and Rivin-Hodgson [19]. 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification. 52B10, 52A55, 51M09. Key Words. Hyperbolic geometry, polyhedra, tetrahedra. Given a combinatorial description C of a polyhedron having E edges, the space of dihedral angles of all compact hyperbolic polyhedra that realize C is generally not a convex subset of RE. This is proved in a nice paper by D´ıaz [9]. However, Andreev’s Theorem [5, 13, 14, 20] shows that by restricting to compact hyperbolic polyhedra with non-obtuse dihedral angles, E the space of dihedral angles is a convex polytope, which we label AC R . It is interesting to note that the statement of Andreev’s Theorem requires⊂ ∗rroeder@fields.utoronto.ca 1 that C have five or more faces, ruling out the tetrahedron which is the only polyhedron having fewer than five faces. -

Using Information Theory to Discover Side Chain Rotamer Classes

Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing 4:278-289 (1999) U S I N G I N F O R M A T I O N T H E O R Y T O D I S C O V E R S I D E C H A I N R O T A M E R C L A S S E S : A N A L Y S I S O F T H E E F F E C T S O F L O C A L B A C K B O N E S T R U C T U R E J A C Q U E L Y N S . F E T R O W G E O R G E B E R G Department of Molecular Biology Department of Computer Science The Scripps Research Institute University at Albany, SUNY La Jolla, CA 92037, USA Albany, NY 12222, USA An understanding of the regularities in the side chain conformations of proteins and how these are related to local backbone structures is important for protein modeling and design. Previous work using regular secondary structures and regular divisions of the backbone dihedral angle data has shown that these rotamers are sensitive to the protein’s local backbone conformation. In this preliminary study, we demonstrate a method for combining a more general backbone structure model with an objective clustering algorithm to investigate the effects of backbone structures on side chain rotamer classes and distributions. For the local structure classification, we use the Structural Building Blocks (SBB) categories, which represent all types of secondary structure, including regular structures, capping structures, and loops. -

Prebiological Evolution and the Metabolic Origins of Life

Prebiological Evolution and the Andrew J. Pratt* Metabolic Origins of Life University of Canterbury Keywords Abiogenesis, origin of life, metabolism, hydrothermal, iron Abstract The chemoton model of cells posits three subsystems: metabolism, compartmentalization, and information. A specific model for the prebiological evolution of a reproducing system with rudimentary versions of these three interdependent subsystems is presented. This is based on the initial emergence and reproduction of autocatalytic networks in hydrothermal microcompartments containing iron sulfide. The driving force for life was catalysis of the dissipation of the intrinsic redox gradient of the planet. The codependence of life on iron and phosphate provides chemical constraints on the ordering of prebiological evolution. The initial protometabolism was based on positive feedback loops associated with in situ carbon fixation in which the initial protometabolites modified the catalytic capacity and mobility of metal-based catalysts, especially iron-sulfur centers. A number of selection mechanisms, including catalytic efficiency and specificity, hydrolytic stability, and selective solubilization, are proposed as key determinants for autocatalytic reproduction exploited in protometabolic evolution. This evolutionary process led from autocatalytic networks within preexisting compartments to discrete, reproducing, mobile vesicular protocells with the capacity to use soluble sugar phosphates and hence the opportunity to develop nucleic acids. Fidelity of information transfer in the reproduction of these increasingly complex autocatalytic networks is a key selection pressure in prebiological evolution that eventually leads to the selection of nucleic acids as a digital information subsystem and hence the emergence of fully functional chemotons capable of Darwinian evolution. 1 Introduction: Chemoton Subsystems and Evolutionary Pathways Living cells are autocatalytic entities that harness redox energy via the selective catalysis of biochemical transformations. -

Chapter 3 • Ratio: Cnh2n+2

Organic Chemistry, 5th Edition Alkane Formulas L. G. Wade, Jr. • All C-C single bonds • Saturated with hydrogens Chapter 3 • Ratio: CnH2n+2 Structure and Stereochemistry • Alkane homologs: CH3(CH2)nCH3 of Alkanes • Same ratio for branched alkanes H H H H H H CH H C C C C H H H H C CCH Jo Blackburn H H H H H H Richland College, Dallas, TX H => Butane, C4H10 Dallas County Community College District Chapter 3Isobutane, C H 2 © 2003, Prentice Hall 4 10 Common Names Pentanes H H H H H H H CH • Isobutane, “isomer of butane” H C C C C C H H H • Isopentane, isohexane, etc., methyl H H H H H H H C CCC H branch on next-to-last carbon in chain. H H H H • Neopentane, most highly branched n-pentane, C5H12 isopentane, C5H12 • Five possible isomers of hexane, CH3 18 isomers of octane and 75 for H3C C CH3 decane! CH3 => => neopentane, C5H12 Chapter 3 3 Chapter 3 4 Longest Chain IUPAC Names • The number of carbons in the longest • Find the longest continuous carbon chain determines the base name: chain. ethane, hexane. (Listed in Table 3.2, • Number the carbons, starting closest to page 81.) the first branch. • If there are two possible chains with the • Name the groups attached to the chain, same number of carbons, use the chain using the carbon number as the locator. with the most substituents. • Alphabetize substituents. H3C CH CH CH • Use di-, tri-, etc., for multiples of same 2 3 CH3 substituent. -

Stereochemistry of Alkanes and Cycloalkanes

STEREOCHEMISTRY OF ALKANES AND CYCLOALKANES CONFORMATIONAL ISOMERS 1 CONFORMATIONAL ISOMERS • Stereochemistry concerned with the 3-D aspects of molecules • Rotation is possible around C-C bonds in open- chain molecules • A conformation is one of the many possible arrangements of atoms caused by rotation about a single bond, and a specific conformation is called a conformer (conformational isomer). 2 SOME VOCABULARY • A staggered conformation is the conformation in which all groups on two adjacent carbons are as far from each other as possible. • An eclipsed conformation is the conformation in which all groups on two adjacent carbons are as close to each other as possible. • Dihedral angle is angle between the substituents on two adjacent carbons; changes with rotation around the C-C bond 3 MORE VOCABULARY • Angle strain is the strain caused by the deformation of a bond angle from its normal value. • Steric strain is the repulsive interaction caused by atoms attempting to occupy the same space. • Torsional strain is the repulsive interaction between two bonds as they rotate past each other. Torsional strain is responsible for the barrier to rotation around the C-C bond. The eclipsed from higher in energy than the staggered form. 4 CONFORMATION OF ETHANE • Conformation- Different arrangement of atoms resulting from bond rotation • Conformations can be represented in 2 ways: 5 TORSIONAL STRAIN • We do not observe perfectly free rotation • There is a barrier to rotation, and some conformers are more stable than others • Staggered- most stable: -

A Reminder… Chirality: a Type of Stereoisomerism

A Reminder… Same molecular formula, isomers but not identical. constitutional isomers stereoisomers Different in the way their Same connectivity, but different atoms are connected. spatial arrangement. and trans-2-butene cis-2-butene are stereoisomers. Chirality: A Type of Stereoisomerism Any object that cannot be superimposed on its mirror image is chiral. Any object that can be superimposed on its mirror image is achiral. Chirality: A Type of Stereoisomerism Molecules can also be chiral or achiral. How do we know which? Example #1: Is this molecule chiral? 1. If a molecule can be superimposed on its mirror image, it is achiral. achiral. Mirror Plane of Symmetry = Achiral Example #1: Is this molecule chiral? 2. If you can find a mirror plane of symmetry in the molecule, in any achiral. conformation, it is achiral. Can subject unstable conformations to this test. ≡ achiral. Finding Chirality in Molecules Example #2: Is this molecule chiral? 1. If a molecule cannot be superimposed on its mirror image, it is chiral. chiral. The mirror image of a chiral molecule is called its enantiomer. Finding Chirality in Molecules Example #2: Is this molecule chiral? 2. If you cannot find a mirror plane of symmetry in the molecule, in any conformation, it is chiral. chiral. (Or maybe you haven’t looked hard enough.) Pharmacology of Enantiomers (+)-esomeprazole (-)-esomeprazole proton pump inhibitor inactive Prilosec: Mixture of both enantiomers. Patent to AstraZeneca expired 2002. Nexium: (+) enantiomer only. Process patent coverage to 2007. More examples at http://z.umn.edu/2301drugs. (+)-ibuprofen (-)-ibuprofen (+)-carvone (-)-carvone analgesic inactive (but is converted to spearmint oil caraway oil + enantiomer by an enzyme) Each enantiomer is recognized Advil (Wyeth) is a mixture of both enantiomers. -

Pyrethroid Stereoisomerism: Diastereomeric and Enantiomeric Selectivity in Environmental Matrices – a Review

Orbital: The Electronic Journal of Chemistry journal homepage: www.orbital.ufms.br e-ISSN 1984-6428 | Vol 10 | | No. 4 | | Special Issue June 2018 | REVIEW Pyrethroid Stereoisomerism: Diastereomeric and Enantiomeric Selectivity in Environmental Matrices – A Review Cláudio Ernesto Taveira Parente*, Claudio Eduardo Azevedo-Silva, Rodrigo Ornellas Meire, and Olaf Malm Laboratório de Radioisótopos, Instituto de Biofísica, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Av. Carlos Chagas Filho s/n, bloco G, sala 60, subsolo - 21941-902. Cidade Universitária, Rio de Janeiro, RJ. Brasil. Article history: Received: 30 July 2017; revised: 10 October 2017; accepted: 08 March 2018. Available online: 11 March 2018. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17807/orbital.v10i4.1057 Abstract: Pyrethroids are chiral insecticides characterized by stereoisomerism, which occurs due to the presence of one to three asymmetric (chiral) carbons, generating one or two pairs of cis/trans diastereomers, and two or four pairs of enantiomers. Diastereomers have equal chemical properties and different physical properties, while enantiomer pairs, have the same physicochemical properties, with exception by the ability to deviate the plane of polarized light to the right or to the left. However, stereoisomers exhibit different toxicities at the metabolic level, presenting enzyme and receptor selectivity in biological systems. Studies in aquatic organisms have shown that toxic effects are caused by specific enantiomers (1R-cis and 1R-trans) and that those cause potential estrogenic effects (1S-cis and 1S- trans). In this context, the same compound can have wide-ranging effects in organisms. Therefore, several studies have highlighted pyrethroid stereochemical selectivity in different environmental matrices. The analytical ability to distinguish the diastereomeric and enantiomeric patterns of these compounds is fundamental for understanding the processes of biotransformation, degradation environmental behavior and ecotoxicological impacts. -

![Chapter 5: Stereoisomerism [Sections: 5.1-5.9]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1578/chapter-5-stereoisomerism-sections-5-1-5-9-331578.webp)

Chapter 5: Stereoisomerism [Sections: 5.1-5.9]

Chapter 5: Stereoisomerism [Sections: 5.1-5.9] 1. Identifying Types of Isomers Same MolecularFormula? NO YES A B C compounds are not isomers Same Connectivity? NO YES D E Different Orientation constitutional of Substituents isomers in Space? verify by: A vs B? • have different names (parent name is different or numbering [locants] of substituents) A vs C? • nonsuperimposable C vs D? YES NO D vs E? C vs E? B vs E? stereoisomers same molecule verify by: • both must have the same name • two must be superimposable P: 5.57 2. Defining Chirality • a chiral object is any object with a non-superimposable mirror image • the mirror image of a chiral object is not identical (i.e., not superimposable) • an achiral object is any object with a superimposable mirror image • the mirror image of an achiral object is identical (i.e., superimposable) # different types of groups and/or atoms the central atom is attached to: mirror image superimposable? chiral? • molecules can also be chiral • the mirror image of a chiral molecule is non-superimposable and is therefore an isomer • since the two mirror image compounds have the same connectivity, they are NOT constitutional isomers • the two mirror image compounds are nonsuperimposable due to different orientations of substituents in space: stereoisomers • non-superimposable stereoisomers that bear a mirror-image relationship are enantiomers • stereoisomers that do NOT bear a mirror-image relationship are diastereomers stereoisomers Mirror Image Relationship? NO YES diastereomers enantiomers verify by: verify by: • names differ by cis/trans, E/Z or • names differ by by having different R and S having exactly configurations at one or more opposite R and S chirality centers (but not exactly configurations at opposite configurations from each every chirality center other) 3. -

Introduction to Organic Chemistry 2018 More

Introduction to Organic Chemistry 25 Introduction to Organic Chemistry Handout 2 - Stereochemistry OH O O OH enantiomers Me OH HO Me A B NH2 NH2 diastereomers diastereomers diastereomers OH O O OH Me OH HO Me C D NH2 enantiomers NH2 http://burton.chem.ox.ac.uk/teaching.html ◼ Organic Chemistry J. Clayden, N. Greeves, S. Warren ◼ Stereochemistry at a Glance J. Eames & J. M. Peach ◼ The majority of organic chemistry text books have good chapters on the topics covered by these lectures ◼ Eliel Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds (advanced reference text) Introduction to Organic Chemistry 26 ◼ representations of formulae in organic chemistry ◼ skeletal representations are far less cluttered and as a result are much clearer than drawing all carbon and hydrogen atoms explicitly, they also give a much better representation of the likely bond angles and hence hybridisation states of the carbon atoms ◼ skeletal representations allow functional groups (sites of reactivity) to be clearly seen ◼ guidelines for drawing skeletal structures i) draw chains of atoms as zig-zags ii) do not draw C atoms unless there is good reason to draw them iii) do not draw C-H bonds unless there is good reason to draw then iv) do not draw Hs attached to carbon atoms unless there is good reason to draw them v) make drawings realistic Introduction to Organic Chemistry 27 ◼ representing structures in three dimensions ◼ a wedged bond indicates the bond is projecting out in front of the plane of the paper ◼ a dashed bond indicates the bond is projecting behind the plane -

Chapter 4: Stereochemistry Introduction to Stereochemistry

Chapter 4: Stereochemistry Introduction To Stereochemistry Consider two of the compounds we produced while finding all the isomers of C7H16: CH3 CH3 2-methylhexane 3-methylhexane Me Me Me C Me H Bu Bu Me Me 2-methylhexane H H mirror Me rotate Bu Me H 2-methylhexame is superimposable with its mirror image Introduction To Stereochemistry Consider two of the compounds we produced while finding all the isomers of C7H16: CH3 CH3 2-methylhexane 3-methylhexane H C Et Et Me Pr Pr 3-methylhexane Me Me H H mirror Et rotate H Me Pr 2-methylhexame is superimposable with its mirror image Introduction To Stereochemistry Consider two of the compounds we produced while finding all the isomers of C7H16: CH3 CH3 2-methylhexane 3-methylhexane .Compounds that are not superimposable with their mirror image are called chiral (in Greek, chiral means "handed") 3-methylhexane is a chiral molecule. .Compounds that are superimposable with their mirror image are called achiral. 2-methylhexane is an achiral molecule. .An atom (usually carbon) with 4 different substituents is called a stereogenic center or stereocenter. Enantiomers Et Et Pr Pr Me CH3 Me H H 3-methylhexane mirror enantiomers Et Et Pr Pr Me Me Me H H Me H H Two compounds that are non-superimposable mirror images (the two "hands") are called enantiomers. Introduction To Stereochemistry Structural (constitutional) Isomers - Compounds of the same molecular formula with different connectivity (structure, constitution) 2-methylpentane 3-methylpentane Conformational Isomers - Compounds of the same structure that differ in rotation around one or more single bonds Me Me H H H Me H H H H Me H Configurational Isomers or Stereoisomers - Compounds of the same structure that differ in one or more aspects of stereochemistry (how groups are oriented in space - enantiomers or diastereomers) We need a a way to describe the stereochemistry! Me H H Me 3-methylhexane 3-methylhexane The CIP System Revisited 1. -

Predicting Backbone Cα Angles and Dihedrals from Protein Sequences by Stacked Sparse Auto-Encoder Deep Neural Network

Predicting backbone C# angles and dihedrals from protein sequences by stacked sparse auto-encoder deep neural network Author Lyons, James, Dehzangi, Abdollah, Heffernan, Rhys, Sharma, Alok, Paliwal, Kuldip, Sattar, Abdul, Zhou, Yaoqi, Yang, Yuedong Published 2014 Journal Title Journal of Computational Chemistry DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.23718 Copyright Statement © 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.. This is the accepted version of the following article: Predicting backbone Ca angles and dihedrals from protein sequences by stacked sparse auto-encoder deep neural network Journal of Computational Chemistry, Vol. 35(28), 2014, pp. 2040-2046, which has been published in final form at dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcc.23718. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/64247 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Predicting backbone Cα angles and dihedrals from protein sequences by stacked sparse auto-encoder deep neural network James Lyonsa, Abdollah Dehzangia,b, Rhys Heffernana, Alok Sharmaa,c, Kuldip Paliwala , Abdul Sattara,b, Yaoqi Zhoud*, Yuedong Yang d* aInstitute for Integrated and Intelligent Systems, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia bNational ICT Australia (NICTA), Brisbane, Australia cSchool of Engineering and Physics, University of the South Pacific, Private Mail Bag, Laucala Campus, Suva, Fiji dInstitute for Glycomics and School of Information and Communication Technique, Griffith University, Parklands Dr. Southport, QLD 4222, Australia *Corresponding authors ([email protected], [email protected]) ABSTRACT Because a nearly constant distance between two neighbouring Cα atoms, local backbone structure of proteins can be represented accurately by the angle between Cαi-1−Cαi−Cαi+1 (θ) and a dihedral angle rotated about the Cαi−Cαi+1 bond (τ).