Juilliard Orchestra Alan Gilbert , Conductor Giorgio Consolati , Flute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

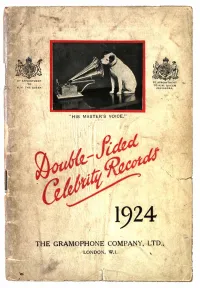

029I-HMVCX1924XXX-0000A0.Pdf

This Catalogue contains all Double-Sided Celebrity Records issued up to and including March 31st, 1924. The Single-Sided Celebrity Records are also included, and will be found under the records of the following artists :-CLARA Burr (all records), CARUSO and MELBA (Duet 054129), CARUSO,TETRAZZINI, AMATO, JOURNET, BADA, JACOBY (Sextet 2-054034), KUBELIK, one record only (3-7966), and TETRAZZINI, one record only (2-033027). International Celebrity Artists ALDA CORSI, A. P. GALLI-CURCI KURZ RUMFORD AMATO CORTOT GALVANY LUNN SAMMARCO ANSSEAU CULP GARRISON MARSH SCHIPA BAKLANOFF DALMORES GIGLI MARTINELLI SCHUMANN-HEINK BARTOLOMASI DE GOGORZA GILLY MCCORMACK Scorn BATTISTINI DE LUCA GLUCK MELBA SEMBRICH BONINSEGNA DE' MURO HEIFETZ MOSCISCA SMIRN6FF BORI DESTINN HEMPEL PADEREWSKI TAMAGNO BRASLAU DRAGONI HISLOP PAOLI TETRAZZINI BI1TT EAMES HOMER PARETO THIBAUD CALVE EDVINA HUGUET PATTt WERRENRATH CARUSO ELMAN JADLOWKER PLANCON WHITEHILL CASAZZA FARRAR JERITZA POLI-RANDACIO WILLIAMS CHALIAPINE FLETA JOHNSON POWELL ZANELLIi CHEMET FLONZALEY JOURNET RACHM.4NINOFF ZIMBALIST CICADA QUARTET KNIIPFER REIMERSROSINGRUFFO CLEMENT FRANZ KREISLER CORSI, E. GADSKI KUBELIK PRICES DOUBLE-SIDED RECORDS. LabelRed Price6!-867'-10-11.,613,616/- (D.A.) 10-inch - - Red (D.B.) 12-inch - - Buff (D.J.) 10-inch - - Buff (D.K.) 12-inch - - Pale Green (D.M.) 12-inch Pale Blue (D.O.) 12-inch White (D.Q.) 12-inch - SINGLE-SIDED RECORDS included in this Catalogue. Red Label 10-inch - - 5'676 12-inch - - Pale Green 12-inch - 10612,615j'- Dark Blue (C. Butt) 12-inch White (Sextet) 12-inch - ALDA, FRANCES, Soprano (Ahl'-dah) New Zealand. She Madame Frances Aida was born at Christchurch, was trained under Opera Comique Paris, Since Marcltesi, and made her debut at the in 1904. -

October 30, 2018

October 30, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window “Music is the social act of communication among people, a gesture of friendship, the strongest there is.” —Malcolm Arnold Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Franck The Breezes (A Symphonic Poem) National Orchestra of Belgium/Cluytens EMI Classics 13207 Awake! 00:13 Buy Now! Vivaldi Trio in G minor for Winds, RV 103 Camerata of Cologne Harmonia Mundi 77018 054727701825 00:23 Buy Now! Brahms Piano Trio No. 1 in B, Op. 8 Trio Fontenay Teldec 9031-76036 090317603629 01:01 Buy Now! Warlock Capriol Suite English Sinfonia/Dilkes EMI 62529 077776252926 01:12 Buy Now! Respighi The Birds Orpheus Chamber Orchestra DG 437 533 N/A 01:32 Buy Now! Mozart String Quartet No. 17 in B flat, K. 458 "Hunt" Alban Berg Quartet Teldec 72480 090317248028 02:00 Buy Now! Handel Flute Sonata in A minor Bruggen/Bylsma/van Asperen Sony 60100 074646010020 Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95 "From the 02:12 Buy Now! Dvorak Houston Symphony/Eschenbach Virgin 91476 075679147622 New World" 03:00 Buy Now! Boccherini Cello Concerto No. 3 in G Bylsma/Tafelmusik/Lamon DHM 7867 054727786723 03:17 Buy Now! Schumann Manfred Overture, Op. 115 Royal Concertgebouw/Haitink Philips 411 104 028941110428 03:30 Buy Now! Franck Violin Sonata in A Mintz/Bronfman DG 415 683 028941568328 First Suite in E flat, Op. 28 No. 1 (for military 03:59 Buy Now! Holst Central Band of the RAF/Banks EMI 49608 077774960823 band) 04:11 Buy Now! Mozart Symphony No. -

June WTTW & WFMT Member Magazine

Air Check Dear Member, The Guide As we approach the end of another busy fiscal year, I would like to take this opportunity to express my The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT heartfelt thanks to all of you, our loyal members of WTTW and WFMT, for making possible all of the quality Renée Crown Public Media Center content we produce and present, across all of our media platforms. If you happen to get an email, letter, 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue or phone call with our fiscal year end appeal, I’ll hope you’ll consider supporting this special initiative at Chicago, Illinois 60625 a very important time. Your continuing support is much appreciated. Main Switchboard This month on WTTW11 and wttw.com, you will find much that will inspire, (773) 583-5000 entertain, and educate. In case you missed our live stream on May 20, you Member and Viewer Services can watch as ten of the area’s most outstanding high school educators (and (773) 509-1111 x 6 one school principal) receive this year’s Golden Apple Awards for Excellence WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 in Teaching. Enjoy a wide variety of great music content, including a Great Chicago Production Center Performances tribute to folk legend Joan Baez for her 75th birthday; a fond (773) 583-5000 look back at The Kingston Trio with the current members of the group; a 1990 concert from the four icons who make up the country supergroup The Websites wttw.com Highwaymen; a rousing and nostalgic show by local Chicago bands of the wfmt.com 1960s and ’70s, Cornerstones of Rock, taped at WTTW’s Grainger Studio; and a unique and fun performance by The Piano Guys at Red Rocks: A Soundstage President & CEO Special Event. -

Richard Lert Papers 0210

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt638nf3ww No online items Finding Aid of the Richard Lert papers 0210 Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Hirsch The processing of this collection and the creation of this finding aid was funded by the generous support of the National Historic Publications and Records Commission. USC Libraries Special Collections Doheny Memorial Library 206 3550 Trousdale Parkway Los Angeles, California, 90089-0189 213-740-5900 [email protected] June 2010 Finding Aid of the Richard Lert 0210 1 papers 0210 Title: Richard Lert papers Collection number: 0210 Contributing Institution: USC Libraries Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 58.51 Linear feet70 boxes Date (inclusive): 1900-1981 Abstract: This collection consists of Richard Lert's video and audio recordings of performances, rehearsals and lectures, personal papers and his music score library. Lert was born in Vienna and trained as an orchestral conductor in Germany. He moved to the United States in 1932 with his family and was the conductor of the Pasadena Symphony Orchestra from 1932 until his retirement in 1972. creator: Lert, Richard, 1885-1980 Biographical Note Richard Lert was born September 19, 1885, in Vienna, Austria. He trained as an orchestral conductor under Arthur Nikisch and began his career in Darmstadt, Germany, where he met and married his wife, Vicki Baum, in 1916. They had two sons. Lert held posts in Frankfurt, Kiel and Hannover before becoming the music director of the Berlin National Opera. Lert and his family moved to Los Angeles in 1932, where he became the music director of the Pasadena Symphony Orchestra. -

Il Trovatore Was Made Stage Director Possible by a Generous Gift from Paula Williams the Annenberg Foundation

ilGIUSEPPE VERDItrovatore conductor Opera in four parts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano and production Sir David McVicar Leone Emanuele Bardare, based on the play El Trovador by Antonio García Gutierrez set designer Charles Edwards Tuesday, September 29, 2015 costume designer 7:30–10:15 PM Brigitte Reiffenstuel lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Il Trovatore was made stage director possible by a generous gift from Paula Williams The Annenberg Foundation The revival of this production is made possible by a gift of the Estate of Francine Berry general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the San Francisco principal conductor Fabio Luisi Opera Association 2015–16 SEASON The 639th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S il trovatore conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance ferr ando Štefan Kocán ines Maria Zifchak leonor a Anna Netrebko count di luna Dmitri Hvorostovsky manrico Yonghoon Lee a zucena Dolora Zajick a gypsy This performance Edward Albert is being broadcast live on Metropolitan a messenger Opera Radio on David Lowe SiriusXM channel 74 and streamed at ruiz metopera.org. Raúl Melo Tuesday, September 29, 2015, 7:30–10:15PM KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Il Trovatore Musical Preparation Yelena Kurdina, J. David Jackson, Liora Maurer, Jonathan C. Kelly, and Bryan Wagorn Assistant Stage Director Daniel Rigazzi Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Yelena Kurdina Assistant to the Costume Designer Anna Watkins Fight Director Thomas Schall Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Cardiff Theatrical Services and Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Lyric Opera of Chicago Costume Shop and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ms. -

Signing Day Brings High School Students

the Irving Rambler www.irvingrambler.com “The Newspaper Irving Reads” February 08, 2007 Obituaries Page 14-15 THIS Movie Times Page 3 Artist exhibit their Vintage Tea invitation Police & Fire Page 2 Boundless Expressions Page 8 Puzzles Page 13 WEEK Sports Page 4-5 Page 6 TTeexasxas RailroadRailroad CommissionCommission recommendsrecommends gasgas ratesrates bebe reducedreduced Texas Railroad Commission Atmos Mid-Tex, a division of charging ratepayers at the same resolutions requiring Atmos to jus- Cities’ decision to the Texas Rail- judges recently ruled that natural Atmos Energy Corporation, is the time the company was reporting tify the monopoly rates it was road Commission and asked the gas rates currently charged by monopoly provider of natural gas that it was earning more money for charging the city and their citizens Commission to approve a $60 mil- Atmos Mid-Tex should be reduced to 1.5 million customers through- shareholders than did TXU Gas, for natural gas. Based on the in- lion rate increase. by $23 million on an annual basis out North Central Texas. Jay the previous utility owner. More formation provided by Atmos, the After a three-week hearing, and that ratepayers are entitled to Doegey, city attorney for the City than 80 city councils throughout city councils voted to reduce the Railroad Commission judges a $2.5 million refund of improper of Arlington, and Chairman of the North Texas individually adopted Atmos’ rates. Atmos appealed the See CITIES, Page 11 surcharges. city coalition challenging Atmos’ The judges’ 186-page decision rates, pointed out that cities have to lower rates is the result of an regulatory authority over natural action initiated by more than 80 gas rates that are charged custom- Texas cities including Irving to ers within city limits and can use investigate whether the rates that that power to ensure monopoly Atmos was charging its customers rates are just and reasonable. -

Monday Playlist

December 23, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “I pay no attention whatever to anybody's praise or blame. I simply follow my own feelings.” — WA Mozart Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online The Christmas Tree, and A Pine Forest in Sleepers, Awake! 00:01 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Dresden State Orchestra/Poschner Sony Classic 88875031652 888750316523 Winter ~ The Nutcracker, Op. 71 Lute Suite in A minor (originally C minor), 00:10 Buy Now! Bach Julian Bream RCA 5841 07863558412 BWV 997 00:31 Buy Now! Mozart Violin Concerto No. 5 in A, K. 219 "Turkish" Frang/Arcangelo/Cohen Warner Classics 0825646276776 825646276776 01:01 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Piano Trio No. 2 in C minor, Op. 66 Perlman/Ma/Ax Sony Classical 52192 886975219223 St. Olaf Choir/Nidaros Cathedral Girls' 01:32 Buy Now! Traditional O come, all ye faithful St. Olaf Records 3501 610295350126 Choir/Armstrong/Brevik 01:38 Buy Now! Mercadante Flute Concerto in E minor Galway/I Solisti Veneti/Scimone RCA 7703 07863577032 02:01 Buy Now! Lauridsen O magnum mysterium Los Angeles Master Chorale/Salamunovich RCM 19605 707651960522 02:07 Buy Now! Leontovych Carol of the Bells Los Angeles Master Chorale/Salamunovich RCM 19605 707651960522 02:09 Buy Now! Schubert Symphony No. 1 in D, D. 82 Hanover Band/Goodman Nimbus 5198 083603519827 02:38 Buy Now! Brahms Cello Sonata No. 1 in E minor, Op. 38 Nelsova/Johannesen CBC 2018 059582201824 Christmas at the Opera House, with Bob 03:00 Buy Now! Chapman Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op. -

Il Trovatore

Synopsis Act I: The Duel Count di Luna is obsessed with Leonora, a young noblewoman in the queen’s service, who does not return his love. Outside the royal residence, his soldiers keep watch at night. They have heard an unknown troubadour serenading Leonora, and the jealous count is determined to capture and punish him. To keep his troops awake, the captain, Ferrando, recounts the terrible story of a gypsy woman who was burned at the stake years ago for bewitching the count’s infant brother. The gypsy’s daughter then took revenge by kidnapping the boy and throwing him into the flames where her mother had died. The charred skeleton of a baby was discovered there, and di Luna’s father died of grief soon after. The gypsy’s daughter disappeared without a trace, but di Luna has sworn to find her. In the palace gardens, Leonora confides in her companion Ines that she is in love with a mysterious man she met before the outbreak of the war and that he is the troubadour who serenades her each night. After they have left, Count di Luna appears, looking for Leonora. When she hears the troubadour’s song in the darkness, Leonora rushes out to greet her beloved but mistakenly embraces di Luna. The troubadour reveals his true identity: He is Manrico, leader of the partisan rebel forces. Furious, the count challenges him to fight to the death. Act II: The Gypsy During the duel, Manrico overpowered the count, but some instinct stopped him from killing his rival. The war has raged on. -

Nielsen Flute Concerto Clarinet Concerto Aladdin Suite

SIGCD477_BookletFINAL*.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 22/12/2016 13:24 Page 1 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. Also available… NIELSEN FLUTE CONCERTO CLARINET CONCERTO 1 1 3 6 4 4 ALADDIN SUITE D D C C G G I I S S SAMUEL COLES FLUTE Bruckner: Symphony No.9 Schubert: Symphony No.9 Philharmonia Orchestra Philharmonia Orchestra MARK VAN DE WIEL CLARINET Christoph von Dohnányi Christoph von Dohnányi SIGCD431 SIGCD461 PAAVO JÄRVI “Beautifully prepared account ... Dohnányi’s new recording "This performance ... goes for broke and succeeds, to the is distinguished by the clarity with which it presents evident rapture of the audience. The Philharmonia is up to Bruckner’s score as well as the excellence of its sound.” all Dohnanyi's and Schubert's steep demands, and I was left Gramophone with a feeling of exhausted exhilaration." BBC Music Magazine Flute Concerto Producer – Andrew Cornall recorded live at Royal Festival Hall, 19 November 2015 Engineer – Jonathan Stokes Editor, Mixing & Mastering – Jonathan Stokes Clarinet Concerto Cover Image – Shutterstock recorded live at Royal Festival Hall, 19 May 2016 Design – Darren Rumney Aladdin Suite P2017 Philharmonia Orchestra recorded at Henry Wood Hall, 20 May 2016 C2017 Signum Records 20 1 291.0mm x 169.5mm SIGCD477_BookletFINAL*.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 22/12/2016 13:24 Page 23 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. PAAVO JÄRVI CARL NIELSEN 1865-1931 reflection and prettiness. 15 years had passed NIELSEN Flute Concerto since the first performance of Nielsen’s Violin PaavFo LJäUrvTi iEs cCurrOenNtlyC CEhiRefT COonductor of the NHK Symphony Orchestra, Artistic Director of the Concerto when the Flute Concerto was DeutCschLeA KRamImNeErpThi lChaOrmNonCie EanRdT thOe founder of the Estonian Festival Orchestra, which brings Allegro moderato introduced in Paris in 1927. -

Toscanini IV – La Scala and the Metropolitan Opera

Toscanini IV – La Scala and the Metropolitan Opera Trying to find a balance between what the verbal descriptions of Toscanini’s conducting during the period of roughly 1895-1915 say of him and what he actually did can be like trying to capture lightning in a bottle. Since he made no recordings before December 1920, and instrumental recordings at that, we cannot say with any real certainty what his conducting style was like during those years. We do know, from the complaints of Tito Ricordi, some of which reached Giuseppe Verdi’s ears, that Italian audiences hated much of what Toscanini was doing: conducting operas at the written tempos, not allowing most unwritten high notes (but not all, at least not then), refusing to encore well-loved arias and ensembles, and insisting in silence as long as the music was being played and sung. In short, he instituted the kind of audience decorum we come to expect today, although of course even now (particularly in Italy and America, not so much in England) we still have audiences interrupting the flow of an opera to inject their bravos and bravas when they should just let well enough alone. Ricordi complained to Verdi that Toscanini was ruining his operas, which led Verdi to ask Arrigo Boïto, whom he trusted, for an assessment. Boïto, as a friend and champion of the conductor, told Verdi that he was simply conducting the operas pretty much as he wrote them and not allowing excess high notes, repeats or breaks in the action. Verdi was pleased to hear this; it is well known that he detested slowly-paced performances of his operas and, worse yet, the interpolated high notes he did not write. -

Mimi Stillman, Artistic Director

Mimi Stillman, Artistic Director Wednesday, February 20, 2019 at 7:00pm Trinity Center for Urban Life 22 nd and Spruce Streets, Philadelphia Dolce Suono Ensemble Presents Rediscoveries: Festival of American Chamber Music I Dolce Suono Trio Mimi Stillman, flute/piccolo – Gabriel Cabezas, cello – Charles Abramovic, piano with Kristina Bachrach, soprano Trio for Flute, Cello, and Piano (1944) Norman Dello Joio (1913-2008) Moderato Adagio Allegro spiritoso Stillman, Cabezas, Abramovic Enchanted Preludes for Flute and Cello (1988) Elliott Carter (1908-2012) Stillman, Cabezas Dozing on the Lawn from Time to the Old (1979) William Schuman (1910-1992) Orpheus with His Lute (1944) Bachrach, Abramovic Winter Spirits for Solo Flute (1997) Katherine Hoover (1937-2018) Stillman Two Songs from Doña Rosita (1943) Irving Fine (1914-1962) (arr. DSE) Stillman, Cabezas, Abramovic Intermission Moon Songs (2011) * Shulamit Ran (1949) Act I: Creation Act II: Li Bai and the Vacant Moon Entr’acte I Act III: Star-crossed Entr’acte II: Prayer to Pierrot Act IV: Medley Bachrach, Stillman, Cabezas, Abramovic Tonight from West Side Story (1961) Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) [premiere of new arrangement ] (arr. Abramovic) Stillman, Cabezas, Abramovic *Commissioned by Dolce Suono Ensemble About the Program – Notes by Mimi Stillman We are pleased to present Dolce Suono Ensemble (DSE)’s new project “Rediscoveries: Festival of American Chamber Music,” which seeks to illuminate an important but largely neglected body of chamber music by American composers. Aside from the most celebrated American composers from this period whose chamber works are regularly performed, i.e. Copland, Barber, Bernstein, and Carter, there are many other composers highly lauded in their time and significant in shaping the story of music in the United States, who are rarely heard today. -

Symphony Orchestra

School of Music ROMANTIC SMORGASBORD Symphony Orchestra Huw Edwards, conductor Maria Sampen, violin soloist, faculty FRIDAY, OCT. 11, 2013 SCHNEEBECK CONCERT HALL 7:30 P.M. First Essay for Orchestra, Opus 12 ............................ Samuel Barber (1910–1983) Violin Concerto in D Major, Opus 77 .........................Johannes Brahms Allegro non troppo--cadenza--tranquillo (1833–1897) Maria Sampen, violin INTERMISSION A Shropshire Lad, Rhapsody for Orchestra ..................George Butterworth (1885–1916) Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Opus 43 ............................Jean Sibelius Allegro moderato--Moderato assai--Molto largamente (1865–1957) SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Huw Edwards, conductor VIOLIN I CELLO FRENCH HORN Zachary Hamilton ‘15, Faithlina Chan ’16, Matt Wasson ‘14 concertmaster principal Billy Murphy ‘16 Marissa Kwong ‘15 Bronwyn Hagerty ‘15 Chloe Thornton ‘14 Jonathan Mei ‘16 Will Spengler ‘17 Andy Rodgers ‘16- Emily Brothers ‘14 Kira Weiss ‘17 Larissa Freier ‘17 Anna Schierbeek ‘16 TRUMPET Sophia El-Wakil ‘16 Aiden Meacham ‘14 Gavin Tranter ‘16 Matt Lam ‘16 Alana Roth ‘14 Lucy Banta ‘17 Linnaea Arnett ‘17 Georgia Martin ‘15 Andy Van Heuit ‘17 Abby Scurfield ‘16 Carolynn Hammen ‘16 TROMBONE VIOLIN II BASS Daniel Thorson ‘15 Clara Fuhrman ‘16, Kelton Mock ‘15 Stephen Abeshima ‘16 principal principal Wesley Stedman ‘16 Rachel Lee ‘15 Stephen Schermer, faculty Sophie Diepenheim ‘14 TUBA Brandi Main ‘16 FLUTE and PICCOLO Scott Clabaugh ‘16 Nicolette Andres ‘15 Whitney Reveyrand ‘15 Lauren Griffin ‘17 Morgan Hellyer ‘14 TIMPANI and