Malaysia Brunei Malaysia at a Glance: 2001-02

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Cabinet Will Lead BN Into

Headline New cabinet will lead BN into GEM MediaTitle New Straits Times Date 28 Jun 2016 Language English Circulation 74,711 Readership 240,000 Section Local News Color Full Color Page No 3 ArticleSize 267 cm² AdValue RM 9,168 PR Value RM 27,504 New cabinet will lead BN into GEM STRATEGIC: Appointments will strengthen coalition ahead of polls, say analysts election. responsibility. "It is a known fact that Noh had "Another Sabahan leader, Datuk made significant contributions to Datu Nasrun Datu Mansur, has also BN's win there. been appointed as a deputy min "I foresee that Noh will have free ister. It is a significant gain for rein over the design and execution Sabah." of BN's battle plan in Selangor." University of Tasmania's Asia In Khoo said the appointment of stitute director Professor Dr James Gerakan president Datuk Seri Mah Chin said Najib's decision not to axe THE unveiling of the new cab Siew Keong as plantation industries any minister from the cabinet meant inet lineup marks an impor and commodities minister was a big that the prime minister was con tant first step by Prime Min win for the multiracial party. fident in his team's strength. ister Datuk Seri Najib Razak in "Mah is now in charge of a min "I am surprised nobody was charting Barisan Nasional's course istry that is traditionally held by a dropped (from cabinet). towards the 14th General Election. Gerakan leader. It's a big morale "It means he has a solid cabinet While many have regarded the booster for the party," he said, that supports him 100 per cent. -

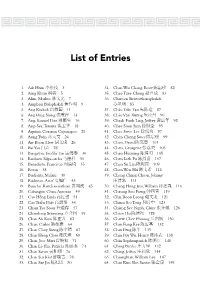

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

Samy Vellu Should Be Commended- Kit Siang

08 NOV 1996 Samy Vellu-Kit Siang SAMY VELLU SHOULD BE COMMENDED- KIT SIANG KUALA LUMPUR, Nov 8 (Bernama) -- Opposition Leader Lim Kit Siang has commended Works Minister Datuk Seri S Samy Vellu for being present in the Dewan Rakyat most of the time this year to answer questions of members. "Samy Velu should be commended as a check with parliamentary records this year show that he had attended the Dewan Rakyat on nine separate sittings to personally respond to questions during question time," he said. Prime Minister Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad, Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim and International Trade and Industry Minister, Datuk Seri Rafidah Aziz had attended parliament on two separate occasions to answer parliamentary questions, he said in a statement here. However, he said both Transport Minister Datuk Seri Dr Ling Liong Sik and Primary Industries Minister Datuk Seri Dr Lim Keng Yaik had never attended parliament during question time to answer questions pertaining to their ministries although parliament is meeting for the fourth time this year. "If Samy Vellu can be in parliament for at least nine days to answer questions in four parliamentary meetings this year, there is no reason why Dr Ling and Dr Lim cannot be equally diligent in discharging their parliamentary duties," he said. Lim said Energy, Telecommunications and Posts Minister Datuk Leo Moggie attended only once during question time to answer a question on Dr Mahathir's visit to the World Solar Summit Conference in Harare, Zimbabwe in September and the government's plan on the use of alternative energy. -

Daim: New Financial Hub Proposal Merits Consideration (NST 11/03

11/03/2000 Daim: New financial hub proposal merits consideration Hardev Kaur in Jakarta JAKARTA, Fri: The proposal for a new financial centre, possibly based in Bandar Seri Begawan, to facilitate financial transactions among Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei, deserves serious consideration despite there being already such centres in East Asia and South-East Asia. Indonesian President Abdurrahman Wahid, who had discussed the proposal with the Sultan of Brunei recently, raised the matter during bilateral talks with Prime Minister Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad at the Merdeka Palace yesterday. Finance Minister Tun Daim Zainuddin said details of the proposal as well as implications of the move must be studied. He was asked whether there is room for another centre, considering there are already Labuan International Offshore Financial Centre (IOFC), the Bangkok Financial Centre, Singapore, Hong Kong and Tokyo. "If there is business, why not?" Daim said. In fact, members of the East Asia Growth Area (EAGA) - Malaysia, Brunei Indonesia and the Philippines - have agreed that the Labuan IOFC serve as the financial centre for the grouping. Even so, the proposal should not be rejected outright, he said, adding that Indonesia and Brunei might have their reasons for suggesting it. When Malaysia decided to set up Labuan IOFC, it undertook several detailed studies including looking at operations of existing financial centres such as the one in the Cayman Islands. Daim is in the high-powered delegation accompanying Dr Mahathir on his two-day official visit here. The Finance Minister, who is also Special Functions Minister, held parallel discussions with his counterpart and the republic's other economic ministers. -

Malasia Malasia

MALASIA MALASIA JUAN JOSÉ RAMÍREZ BONILLA VANESSA A. PROAÑO DOMÍNGUEZ El Colegio de México ECONOMÍA La economía malasia se apega al diagnóstico establecido por los analistas del FMI después del inicio de la crisis asiática: los indicadores macroeco- nómicos eran positivos; la excepción era un desequilibrio en la balanza de cuenta corriente, el cual era considerado por los analistas del FMI como el pro b lema macroeconómico mayor de Malasia y de los países asiáticos más afectados por la crisis del 97 (véase cuadro 1). En el caso malasio, ese déficit fue el resultado de la combinación de un superávit comercial permanente y un déficit crónico en la balanza de servicios. El desequilibrio negativo de la balanza de servicios, a su vez, se debió a un volumen importante de transferencias de capitales al exterior, bajo la forma de ingresos derivados del capital.1 Esta era la consecuencia natural del recurso al ahorro externo que había permitido cerrar la brecha existente entre inversión y ahorro. Los agentes económicos malasios, sin embargo, habían adoptado una actitud diferenciada con respecto al ahorro externo: • El gobierno federal restringió al máximo el recurso al ahorro exter- no: entre 1987 y 1996, la deuda externa del gobierno federal, medida con 1 Durante los noventa, dichas transferencias representaron entre el 4.45% (1990) y el 5.55% (1992); vistas desde otro ángulo,las transferencias crecieron a un ritmo superior al de la economía, excepto en 1993 y 1995. 363 364 ASIA PACÍFICO 2000 MALASIA 365 respecto a la deuda externa total del país (DETP), se redujo del 54.9% al 10.7%. -

Bank Negara Malaysia

Bank Negara Malaysia Statutory Requirements In accordance with Section 48 of the Central Bank of Malaysia Act 1958, Bank Negara Malaysia has transmitted to the Minister of Finance a copy of this Annual Report together with a copy of its Annual Accounts for the year ended 31 December 1997, which have been examined and certified by the Auditor-General and such Accounts will be published in the Gazette. Ahmad Mohd Don Chairman 25 March 1998 Board of Directors Bank Negara Malaysia Board of Directors Tan Sri Dato’ Ahmad bin Mohd Don, P.S.M., D.P.M.J., D.M.S.M. Governor and Chairman Dato’ Fong Weng Phak, D.M.P.N., K.M.N. Deputy Governor Datuk Dr. Aris bin Othman, P.J.N., K.M.N. Secretary-General to the Treasury Encik Oh Siew Nam Dato’ Muhammad Ali bin Hashim, S.P.M.J., D.P.M.J., J.S.M., S.M.J., P.P.B. Tan Sri Datuk Amar Haji Bujang bin Mohd. Nor, P.S.M., D.A., P.N.B.S., J.S.M., J.B.S., A.M.N., P.B.J. Tan Sri Dato’ Dr. Mohd. Noordin bin Md. Sopiee, P.S.M., D.I.M.P., D.M.S.M. Tan Sri Kishu Tirathrai, P.S.M. Datuk Dr. Aris bin Othman was appointed as a member of the Board with effect from 1 January 1998 to replace Tan Sri Datuk Clifford F. Herbert who retired from the Board on 31 December 1997. Tan Sri Kishu Tirathrai was reappointed as a member of the Board effective 1 February 1998. -

DIGI 160407A.Pdf

1 Step into D’House 3 DiGi in 2006 5 DiGi’s Amazing Malaysians 7 Corporate Information 8 Notice of Annual General Meeting 13 Group Financial Summary 18 Directors’ Profi les 22 Chairman’s Statement 30 CEO’s Statement 39 DiGi Management Team 41 Statement on Corporate Gover nance 48 Statement on Internal Control 50 Additional Compliance Information 51 Audit Committee Report Statements 55 Financial ties 101 List of Proper ent Related Party re of Recurr 103 Disclosu Transactions s’ Shareholdings 106 Statement of Director on Shareholdings 107 Statistics 110 Form of Proxy Directory 112 Corporate Coming together We will remember 2006 as the year when DiGizens, scattered across six locations around Shah Alam for a long while, came together in the most memorable way! It wasn’t that the distance between the offi ces stopped us from growing. We had already learnt you can’t put a good brand down. So, despite being away from each other, DiGizens continued to work as one team under the DiGi banner. It never stopped us from being daring, dynamic and different. So, fi nally coming together into D’House was extremely special for us. It began as a dream When we began to dream of our new home, we wanted it to be really different. We wanted it to refl ect our feelings about what it meant to be a DiGizen. We also wanted it to capture the spirit of creativity and innovation that spurred us on, day after day, to be the best. That was how it began. We thought about the values D’House should refl ect and it wasn’t hard - Simplicity, Innovation and Best Value. -

Peny Ata Rasmi Parlimen

Jilid 1 Harl Khamis Bil. 68 15hb Oktober, 1987 MAL AYSIA PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DEWAN RAKYAT House of Representatives P ARLIMEN KETUJUH Seventh Parliament PENGGAL PERTAMA First Session KANDUNGANNYA JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MULUT BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN [Ruangan 11433] USUL-USUL: Akta Acara Kewangan 1957- Menambah Butiran Baru "Kumpulan Wang Amanah Pembangunan Ekonomi Belia", dan "Tabung Amanah Taman Laut dan Rezab Laut" [Ruangan 11481] Akta Persatuan Pembangunan Antarabangsa 1960-Caruman Malaysia [Ruangan 11489] RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Kumpulan Wang Amanah Negara [Ruangan 11492] Dl(;ETA� OLEH JABATAN P1UlC£TAJtAN NEGARA. KUALA LUMPUR HA.JI MOKHTAR SMAMSUDDlN.1.$.D., S,M,T., $,M.S., S.M.f'., X.M.N., P.l.S., KETUA PS.NOAK.AH 1988 MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT YANG KETUJUH Penyata Rasmi Parlimen PENGGAL YANG PERTAMA AHLI-AHLI DEWAN RAKYAT Yang Berhormat Tuan Yang di-Pertua, TAN SRI DATO' MOHAMED ZAHIR BIN HAJI ISMAIL, P.M.N., S.P.M.K., D.S.D.K., J.M.N. Yang Amat Berhormat Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Dalam Negeri dan Menteri Kehakiman, DATO' SERI DR MAHATHIR BIN MOHAMAD, s.s.D.K., S.S.A.P., S.P.M.S., S.P.M.J., D.P., D.U.P.N., S.P.N.S., S.P.D.K., s.P.C.M., s.s.M.T., D.U.N.M., P.1.s. (Kubang Pasu). Timbalan Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Pembangunan Negara " dan Luar Bandar, TUAN ABDUL GHAFAR BIN BABA, (Jasin). Yang Berhormat Menteri Pengangkutan, DATO DR LING LIONG SIK, D.P.M.P. (Labis). Menteri Kerjaraya, DATO' S. -

Download Soalan-0-Intro.Pdf

MESYUARAT PERTAMA, PENGGAL KEENAM PARLIMEN KETIGA BELAS 2018 Jawapan-Jawapan Pertanyaan Jawab Lisan Harian Yang Tidak Dapat Dijawab Dalam Dewan Rakyat Daripada Kementerian HARIISNIN : 2 APRIL 2018 CAWANGAN PERUNDANGAN PARLIMEN MALAYSIA. < KANDUNGAN JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN BAGIPERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN JAWAB LISAN YANG TIDAK DIJAWAB DIDALAM DEWAN ( SOALAN, NO.ll HINGGA NO.59 ) NOTA: [RUJUK PENYATA RASMIHARIAN (HANSARD)] MESYUARAT PERTAMA, PENGGAL KEENAM, PARLIMEN KETIGA BELAS PEMBERITAHUAN PERTANYAAN DEWAN RAKYAT MALAYSIA PERTANYAAN JAWAB LISAN DARIPADA DATUK JUSLIE BIN AJIROL [ LIBARAN ] TARIKH 2.4.2018 (ISNIN) SOALAN 11 minta MENTERI KEMAJUAN LUAR BANDAR DAN WILAYAH menyatakan adakah Kementerian bercadang untuk menaik taraf dan menambah kapasiti pengeluaran air terkawal loji-loji bekalan air mentah bagi memenuhi keperluan penduduk setempat yang kian bertambah khususnya di kawasan luar bandar Sabah. JAWAPAN : Tuan Yang Di-Pertua, Untuk makluman Yang Berhormat, Kementerian ini sentiasa komited dan bekerjasama dengan Unit Perancangan Ekonomi Negeri (UPEN) Sabah, Kementerian Pembangunan Infrastruktur (KPI) Sabah, Kementerian Pembangunan Luar Bandar (KPLB) Sabah dan Jabatan Air Negeri Sabah (JANS) dalam membantu menyediakan infrastruktur asas bekalan air bersih dan terawat. Penyediaan infrastruktur asas ini termasuklah menaiktaraf dan menambah kapasiti loji- loji rawatan air bagi memenuhi keperluan penduduk di kawasan luar bandar. / SOALAN NO: 12 MESYUARAT PERTAMA, PENGGAL KEENAM PARLIMEN KETIGA BELAS PEMBERITAHUAN PERTANYAAN DEWAN RAKYAT MALAYSIA PERTANYAAN -

The Complete Book

Statutory Requirements In accordance with section 48 of the Central Bank of Malaysia Act 1958, Bank Negara Malaysia hereby publishes and has transmitted to the Minister of Finance a copy of this Annual Report together with a copy of its Annual Accounts for the year ended 31 December 2003, which have been examined and certified by the Auditor-General. The Annual Accounts will also be published in the Gazette. Zeti Akhtar Aziz Chairman 26 March 2004 Board of Directors Board of Directors Dr. Zeti Akhtar Aziz D.K. (Johor), P.S.M., S.S.A.P., D.P.M.J. Governor and Chairman Dato’ Mohd Salleh bin Hj. Harun D.S.D.K. Deputy Governor Dato’ Ooi Sang Kuang D.M.P.N. Deputy Governor Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Dr. Samsudin bin Hitam P.S.M., P.N.B.S., D.C.S.M., S.S.A.P., S.M.J., D.P.M.T., D.P.M.P., J.S.M., K.M.N., A.M.N. Secretary General to the Treasury Datuk Oh Siew Nam P.J.N. Tan Sri Datuk Amar Haji Bujang bin Mohd. Nor P.S.M., D.A., P.N.B.S., J.S.M., J.B.S., A.M.N., P.B.J. P.P.D.(Emas) Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Dr. Mohd. Noordin bin Md. Sopiee P.S.M., D.I.M.P., D.M.S.M., D.G.P.N. Dato’ N. Sadasivan D.P.M.P., J.S.M., K.M.N. Governor Dr. Zeti Akhtar Aziz Deputy Governor Dato’ Mohd Salleh bin Hj. -

Excerpt: a Conversation with Tan Sri Leo Moggie

EXCERPT: A CONVERSATION WITH TAN SRI LEO MOGGIE PERDANA LEADERSHIP FOUNDATION ORAL HISTORY SERIES THIS ELECTRONIC EDITION IS PUBLISHED BY PERDANA LEADERSHIP FOUNDATION, N0.1, JALAN P8H, PRECINCT 8, 62250 PUTRAJAYA, MALAYSIA WWW.PERDANA.ORG.MY [email protected] FIRST PRINT EDITION 2017 DIGITAL EDITION 2018 © 2018 PERDANA LEADERSHIP FOUNDATION ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE REPRODUCED, COPIED, STORED IN ANY RETRIEVAL SYSTEM OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS – ELECTRONIC, MECHANICAL, PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING OR OTHERWISE; WITHOUT PRIOR PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM PERDANA LEADERSHIP FOUNDATION. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED WITHIN THIS PUBLICATION ARE STRICTLY THE INTERVIEWEE’S AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE FOUNDATION. PROFILE TAN SRI LEO MOGGIE Tan Sri Leo Moggie was born on 1st October 1941 in Kanowit, Sarawak, Malaysia. He began his career as a civil servant in the Sarawak State Civil Service from 1966 to 1974. His career in politics began soon after when Tan Sri Leo contested and won the Machan State Constituency seat and the Kanowit Parlia- mentary seat in 1978. During his term as a member of Sarawak’s State Assembly from 1974 to 1978, Tan Sri Leo served as Minister of Welfare Services (1976– 1977) and Minister of Local Government (1977–1978). Tan Sri joined the Federal Cabinet from 1978 to 2004 as Minister of Energy, Telecommunications and Posts (1978– 1989), Minister of Works (1989-1995), again as Minister of Energy, Telecommunications and Posts (1995-1998) and as Minister of Energy, Communications and Multimedia (1998 to 2004). He retired from active politics in 2004. -

K a N D U N G a N

K A N D U N G A N JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN LISAN BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN (Halaman 1) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Perbekalan Tambahan (2003) 2003 (Halaman 16) USUL-USUL: Anggaran Pembangunan (Tambahan) (Bil. 1) 2003 (Halaman 16) Waktu Mesyuarat dan Urusan Dibebaskan Daripada Peraturan Mesyuarat (Halaman 66) Diterbitkan Oleh: CAWANGAN DOKUMENTASI PARLIMEN MALAYSIA 2003 DR.8.9.2003 i AHLI-AHLI DEWAN RAKYAT Yang Amat Berbahagia Tuan Yang di-Pertua, Tun Dato Seri Dr. Mohamed Zahir bin Haji Ismail, S.S.M., P.M.N., S.S.D.K., S.P.M.K., D.S.D.K., J.M.N. Yang Amat Berhormat Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Kewangan, Dato Seri Dr. Mahathir bin Mohamad, D.K.(Brunei), D.K.(Perlis), D.K.(Johor), D.U.K., S.S.D.K., S.S.A.P., S.P.M.S., S.P.M.J., D.P. (Sarawak), D.U.P.N., S.P.N.S., S.P.D.K., S.P.C.M., S.S.M.T., D.U.M.N., P.I.S. (Kubang Pasu) “ Timbalan Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Dalam Negeri, Dato’ Seri Abdullah bin Haji Ahmad Badawi, D.G.P.N., D.S.S.A., D.M.P.N., D.J.N., K.M.N., A.M.N., S.P.M.S. (Kepala Batas) “ Menteri Perumahan dan Kerajaan Tempatan, Dato’ Seri Ong Ka Ting, D.P.M.P. (Pontian) “ Menteri Kerja Raya, Dato’ Seri S. Samy Vellu, S.P.M.J., S.P.M.P., D.P.M.S., P.C.M., A.M.N. (Sungai Siput) “ Menteri Perusahaan Utama, Dato’ Seri Dr.