Dziga Vertov As Theorist Vlada Petric

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dziga Vertov — Boris Kaufman — Jean Vigo E

2020 ВЕСТНИК САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГСКОГО УНИВЕРСИТЕТА Т. 10. Вып. 4 ИСКУССТВОВЕДЕНИЕ КИНО UDC 791.2 Dziga Vertov — Boris Kaufman — Jean Vigo E. A. Artemeva Mari State University, 1, Lenina pl., Yoshkar-Ola, 424000, Russian Federation For citation: Artemeva, Ekaterina. “Dziga Vertov — Boris Kaufman — Jean Vigo”. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Arts 10, no. 4 (2020): 560–570. https://doi.org/10.21638/spbu15.2020.402 The article is an attempt to discuss Dziga Vertov’s influence on French filmmakers, in -par ticular on Jean Vigo. This influence may have resulted from Vertov’s younger brother, Boris Kaufman, who worked in France in the 1920s — 1930s and was the cinematographer for all of Vigo’s films. This brother-brother relationship contributed to an important circulation of avant-garde ideas, cutting-edge cinematic techniques, and material objects across Europe. The brothers were in touch primarily by correspondence. According to Boris Kaufman, dur- ing his early career in France, he received instructions from his more experienced brothers, Dziga Vertov and Mikhail Kaufman, who remained in the Soviet Union. In addition, Vertov intended to make his younger brother become a French kinok. Also, À propos de Nice, Vigo’s and Kaufman’s first and most “vertovian” film, was shot with the movable hand camera Kina- mo sent by Vertov to his brother. As a result, this French “symphony of a Metropolis” as well as other films by Vigo may contain references to Dziga Vertov’s and Mikhail Kaufman’sThe Man with a Movie Camera based on framing and editing. In this perspective, the research deals with transnational film circulations appealing to the example of the impact of Russian avant-garde cinema on Jean Vigo’s films. -

Soviet Cinema

Soviet Cinema: Film Periodicals, 1918-1942 Where to Order BRILL AND P.O. Box 9000 2300 PA Leiden The Netherlands RUSSIA T +31 (0)71-53 53 500 F +31 (0)71-53 17 532 BRILL IN 153 Milk Street, Sixth Floor Boston, MA 02109 USA T 1-617-263-2323 CULTURE F 1-617-263-2324 For pricing information, please contact [email protected] MASS www.brill.nl www.idc.nl “SOVIET CINemA: Film Periodicals, 1918-1942” collections of unique material about various continues the new IDC series Mass Culture and forms of popular culture and entertainment ENTERTAINMENT Entertainment in Russia. This series comprises industry in Tsarist and Soviet Russia. The IDC series Mass Culture & Entertainment in Russia The IDC series Mass Culture & Entertainment diachronic dimension. It includes the highly in Russia comprises collections of extremely successful collection Gazety-Kopeiki, as well rare, and often unique, materials that as lifestyle magazines and children’s journals offer a stunning insight into the dynamics from various periods. The fifth sub-series of cultural and daily life in Imperial and – “Everyday Life” – focuses on the hardship Soviet Russia. The series is organized along of life under Stalin and his somewhat more six thematic lines that together cover the liberal successors. Finally, the sixth – “High full spectrum of nineteenth- and twentieth Culture/Art” – provides an exhaustive century Russian culture, ranging from the overview of the historic avant-garde in Russia, penny press and high-brow art journals Ukraine, and Central Europe, which despite in pre-Revolutionary Russia, to children’s its elitist nature pretended to cater to a mass magazines and publications on constructivist audience. -

Dziga Vertov, the First Shoemaker of Russian Cinema1

Dziga Vertov, The First Shoemaker of Russian Cinema1 Devin Fore Princeton University Abstract We are told that the mechanization of production has dire effects on the functionality of language as well as human capacities for symbolic communication in general. This expropriation of language by the machine results in the deterioration of the traditional political public sphere, which once privileged language as the exclusive medium of intersubjectivity and agency. The essay argues that the work of the Soviet media artist Dziga Vertov, especially his 1931 “film-thing” En- thusiasm, sought to redress the antagonism between technology and politics faced by modern industrial societies. Vertov’s public sphere was one that did not privilege language and abstract discourse, but that incorporated all manner of material objects as means of commu- nication. As Vertov instructed, the public sphere must move beyond its linguistic bias to embrace industrial commodities as communica- tive social media. 1. This article is excerpted from a longer paper that examines Dziga Vertov’s work with television, but that cannot appear here in its entirety because of exigencies of space. Postponing the discussion of early television’s position within the Soviet media land- scape for a later context, the present article limits itself to the exposition of two argu- ments: the first section addresses the fate of political discourse within modern regimes of industrial production; then, through an analysis of one passage from Vertov’s film Enthusiasm (1931), the second section considers Vertov’s strategies for forging new modes of political agency within the sphere of technical production. Configurations, 2010, 18:363–382 © 2011 by The Johns Hopkins University Press and the Society for Literature and Science. -

Experiments in Sound and Electronic Music in Koenig Books Isbn 978-3-86560-706-5 Early 20Th Century Russia · Andrey Smirnov

SOUND IN Z Russia, 1917 — a time of complex political upheaval that resulted in the demise of the Russian monarchy and seemingly offered great prospects for a new dawn of art and science. Inspired by revolutionary ideas, artists and enthusiasts developed innumerable musical and audio inventions, instruments and ideas often long ahead of their time – a culture that was to be SOUND IN Z cut off in its prime as it collided with the totalitarian state of the 1930s. Smirnov’s account of the period offers an engaging introduction to some of the key figures and their work, including Arseny Avraamov’s open-air performance of 1922 featuring the Caspian flotilla, artillery guns, hydroplanes and all the town’s factory sirens; Solomon Nikritin’s Projection Theatre; Alexei Gastev, the polymath who coined the term ‘bio-mechanics’; pioneering film maker Dziga Vertov, director of the Laboratory of Hearing and the Symphony of Noises; and Vladimir Popov, ANDREY SMIRNO the pioneer of Noise and inventor of Sound Machines. Shedding new light on better-known figures such as Leon Theremin (inventor of the world’s first electronic musical instrument, the Theremin), the publication also investigates the work of a number of pioneers of electronic sound tracks using ‘graphical sound’ techniques, such as Mikhail Tsekhanovsky, Nikolai Voinov, Evgeny Sholpo and Boris Yankovsky. From V eavesdropping on pianists to the 23-string electric guitar, microtonal music to the story of the man imprisoned for pentatonic research, Noise Orchestras to Machine Worshippers, Sound in Z documents an extraordinary and largely forgotten chapter in the history of music and audio technology. -

Soviet Diy: Samizdat & Hand-Made Books

www.bookvica.com SOVIET DIY: SAMIZDAT & HAND-MADE BOOKS. RECENT ACQUSITIONS 2017 F O R E W O R D Dear friends, Please welcome our latest venture - the October catalogue of 2017. We are always in search for interesting cultural topics to shine the light on, and this time we decided to put together a collection of books made by amateurs and readers to spread the texts that they believed should have been distributed. Soviet State put a great pressure on its citizens, censoring the unwanted content and blocking the books that mattered to people. But in the meantime the process of alternative distribution of the texts was going on. We gathered some of samizdat books, manuscripts, hand-made books to show what was created by ordinary people. Sex manuals, rock’n’roll encyclopedias, cocktail guides, banned literature and unpublished stories by children - all that was hard to find in a Soviet bookshop and hence it makes an interesting reading. Along with this selection you can review our latest acquisitions: we continue to explore the world of pre-WWII architecture with a selection of books containing important theory, unfinished projects and analysis of classic buildings of its time like Lenin’s mausoleum. Two other categories are dedicated to art exhibitions catalogues and books on cinema in 1920s. We are adding one more experimental section this time: the books in the languages of national minorities of USSR. In 1930s the language reforms were going on across the union and as a result some books were created, sometimes in scripts that today no-one is able to read, because they existed only for a short period of time. -

Dziga Vertov, Travel Cinema, and Soviet Patriotism*

Across One Sixth of the World: Dziga Vertov, Travel Cinema, and Soviet Patriotism* OKSANA SARKISOVA The films of Dziga Vertov display a persistent fascination with travel. Movement across vast spaces is perhaps the most recurrent motif in his oeuvre, and the cine-race [kino-probeg]—a genre developed by Vertov’s group of filmmak- ers, the Kinoks 1—stands as an encompassing metaphor for Vertov’s own work. His cinematographic journeys transported viewers to the most remote as well as to the most advanced sites of the Soviet universe, creating a heterogeneous cine-world stretching from the desert to the icy tundra and featuring customs, costumes, and cultural practices unfamiliar to most of his audience. Vertov’s personal travelogue began when he moved from his native Bialystok2 in the ex–Pale of Settlement to Petrograd and later to Moscow, from where, hav- ing embarked on a career in filmmaking, he proceeded to the numerous sites of the Civil War. Recalling his first steps in cinema, Vertov described a complex itin- erary that included Rostov, Chuguev, the Lugansk suburbs, and even the Astrakhan steppes.3 In the early 1920s, when the film distribution network was severely restricted by the Civil War and uneven nationalization, traveling and film- making were inseparable. Along with other filmmakers, he used an improvised * This article is part of my broader research “Envisioned Communities: Representations of Nationalities in Non-Fiction Cinema in Soviet Russia, 1923–1935” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Central European University, 2004). I would like to warmly thank my teachers and friends for sharing their knowledge and enthusiasm throughout this long journey. -

Film and Literary Modernism

Film and Literary Modernism Film and Literary Modernism Edited by Robert P. McParland Film and Literary Modernism, Edited by Robert P. McParland This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Robert P. McParland and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4450-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4450-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 I. City Symphony Films A City Symphony: Urban Aesthetics and the Poetics of Modernism on Screen ................................................................................................... 12 Meyrav Koren-Kuik The Experimental Modernism in the City Symphony Film Genre............ 20 Cecilia Mouat Reconsidering Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand’s Manhatta..................... 27 Kristen Oehlrich II. Perspectives To See is to Know: Avant-Garde Film as Modernist Text ........................ 42 William Verrone Tomato’s Another Day: The Improbable Subversion of James Sibley Watson and Melville Webber .................................................................. -

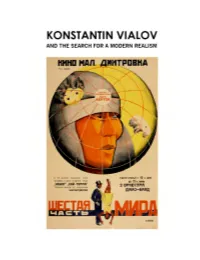

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. -

Dziga Vertov's the Man with the Movie Camera

Contact: Josh Morrison, Operations Manager, [email protected] FLICKER ALLEY PRESENTS DZIGA VERTOV’S THE MAN WITH THE MOVIE CAMERA Flicker Alley, in association with Lobster Films, the Blackhawk Films® Collection, the Cinémathèque de Toulouse, and EYE Film Institute, brings the extraordinary restoration of Dziga Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera to its North American premiere. Flicker Alley, Lobster Films, and the Blackhawk Films® Collection are proud to present the pristine restoration of a cinematic masterpiece from one of the pioneers of Soviet film. Dziga Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera and Other Newly-Restored Works Dziga Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera / 1929 / Directed by Dziga Vertov / 68 minutes / U.S.S.R. / Produced by VUFKU, Goskino, Ukrainfilm, and Mezhrabpom "I am an eye. A mechanical eye. I am the machine that reveals the world to you as only the machine can see it." - Dziga Vertov ("Kino-Eye") These words, written in 1923 (only a year after Robert Flaherty's Nanook of the North was released) reflect the Soviet pioneer's developing approach to cinema as an art form that shuns traditional or Western narrative in favor of images from real life. They lay the foundation for what would become the crux of Vertov's revolutionary, anti-bourgeois aesthetic wherein the camera is an extension of the human eye, capturing "the chaos of visual phenomena filling the universe." Over the next decade-and-a-half, Vertov would devote his life to the construction and organization of these raw images, his apotheosis being the landmark 1929 film The Man with the Movie Camera. -

Soviet Documentary & Propaganda

Soviet documentary & propaganda “Of all arts, the cinema is the most important for us” Lenin Russia • Ruled by the Czar • 1905 Russo-Japanese War • 1905 Revolt • 1914 World War I • 1917 February Czar deposed, Kerensky heads provisional government • 1917 October Bolsheviks seize government, establish Soviet Union (1917-1991) • Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin Montage – Film Editing • Lev Kuleshov – Creative Film Experiments • Eisenstein’s Montage of Attractions Cinema as propaganda 1917 – Bolshevik Revolution 1919 – film industry nationalized VGIK – State Institute of Cinematography – founded Documentary filmmakers of the 1920s: committed Marxists wanted to educate and indoctrinate Soviet people Prominent types of non fiction film in the 1920s: Newsreel-indoctrinational series Compilations of archival footage tracing recent history Epic-scale celebrations of contemporary Soviet life Dziga Vertov • 1896-1954 • Worked on Soviet agitprop train • 1922-25 Kino-Pravda, Kino Eye • 1929 Man With the Movie Camera Kino Glaz theory & practice of filmmaking Close relationship between filming process and human thought “Machine eye” of the camera is more perfect than the eye His film practice demanded anti narrative, antif ictional forms to arrive at the ‘truths’ of the actual world Instead of exotic subjects (Flaherty) Vertov zeroes in on contemporary reality – records facts found in real life The ideological meaning of this reality comes out through editing (montage) – reality ‘deciphered’ by Communist worldview Fascination with technology & machines – futurism & modernity Films by Vertov Kino Pravda - 1922-25 23 series of short films propaganda newsreels, 20 minutes, 3or 4 reports to inform & indoctrinate covering life in the Soviet Union No recreation or direction – ‘life as it is’, ‘life caught unawares’ Nitty-gritty naturalism – vs. -

Adelheid Heftberger Propaganda in Motion Dziga Vertov’S and Aleksandr Medvedkin’S Film Trains and Agit Steamers of the 1920S and 1930S

Adelheid Heftberger Propaganda in Motion Dziga Vertov’s and Aleksandr Medvedkin’s Film Trains and Agit Steamers of the 1920s and 1930s 1 Agit-trains in the 1920s ................................................................................................................... 9 2 Dziga Vertov’s Mobile Cinema: On Reels, on Water, and on the Road................................................ 12 3 We Shoot Today and Show Tomorrow! Medvedkin’s Film Train (kinopoezd) in the 1930s.................... 15 4 The World with the Eye of Millions: Vertov and Medvedkin in the Age of the Internet ....................... 18 Bio.................................................................................................................................................. 20 Bibliography.................................................................................................................................... 20 Filmography .................................................................................................................................... 21 Suggested Citation........................................................................................................................... 22 Abstract: This article focuses on Soviet agit-trains, initiated in the year 1918, as an important instrument forthe dissemination of political propaganda and for the enlightenment of the rural population. These trains werenotonly used to produce and distribute newspapers and leaflets but were additionally equipped with mobile, independent film production -

Film Energy: Process and Metanarrative in Dziga Vertov's The

Film Energy: Process and Metanarrative in Dziga Vertov’s The Eleventh Year (1928)* JOHN MacKAY Historical Prologue With the possible exception of Stride, Soviet [Shagai, Sovet] (1926), The Eleventh Year [Odinnadtsatyi] (1928), Dziga Vertov’s most important film on the great early Soviet theme of electrification and the first of his three Ukrainian productions, is probably the least known and least frequently discussed of Vertov’s major silent documentary features.1 Inaccessibility is surely the prime reason for this neglect: to my knowledge, the film has never been released in any home viewing format in any country, and prints are available in only a few archives worldwide.2 Beyond this, The Eleventh Year, for all the complexity of its montage, imparts a rather sim- ple agitational message, as befits its fundamental purpose as propaganda for the Soviet state’s drive toward industrialization and electrification.3 Beginning with a nearly wordless account of humans and machines collectively overcoming nature’s stony inertia to mobilize water and coal for human (specifically, agricultural and * I would like to thank Annette Michelson, Elizabeth Papazian, Malcolm Turvey, and the students in “Russian Film from the Beginnings to 1945” (2005) at Yale for the many thoughtful remarks that helped me think through the issues discussed in this essay. 1. The other two Ukrainian productions were Man with a Movie Camera (1929) and Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass (1931). Though sections of the major studies in Russian by N. P. Abramov (Dziga Vertov [Moscow: Akademiia Nauk, 1962]) and Lev Roshal’ (Dziga Vertov [Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1982]) have discussed the film, I know of no full-length essay in any language devoted exclusively or even in large part to The Eleventh Year.