10607.Ch01.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue of the Year the Splintered State of Fair-Trade Coffee

TRENDS by Dan Leif issuE of ThE YEaR The splinTered sTaTe of fair-Trade coffee When Fair Trade USA announced last September that it FTUSA’s decision to separate from Fairtrade International was was splitting from longtime parent organization Fairtrade part of a play to grow fair trade on both ends of the supply chain. International, the feedback from some segments of the American Last year FTUSA unveiled a push called Fair Trade for All, with fair-trade-coffee community was biting and resounding. “It’s a the stated goal of doubling the organization’s impact by 2015, betrayal,” Rink Dickinson, co-executive director of roaster Equal and it felt it could more effectively do so by flying solo. As part Exchange, told The New York Times. of its long-term effort to bring more producers into the system, Seemingly overnight, the country’s fair-trade arena became FTUSA launched a pilot project to open fair-trade certification fractured—and a whole lot more confusing to the average spe- to estates and small independent farmers, and it was this idea cialty coffee professional. For well over a decade, American coffee that sparked the wrath of Equal Exchange and a group of other companies had used the certification as a tool to clearly com- fair traders who hold strongly to the notion that when it comes municate business and sourcing ethics to customers. However, in to coffee growing, only small farmers organized into co-ops the months since FTUSA’s announcement should be eligible for fair-trade premi- (and official separation from Fairtrade ums and other producer benefits. -

Starbucks Vs. Equal Exchange: Assessing the Human Costs of Economic Globalization

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Anthropologist Anthropology, Department of 1997 Starbucks vs. Equal Exchange: Assessing the Human Costs of Economic Globalization Lindsey M. Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro Part of the Anthropology Commons Smith, Lindsey M., "Starbucks vs. Equal Exchange: Assessing the Human Costs of Economic Globalization" (1997). Nebraska Anthropologist. 111. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro/111 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Anthropologist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Starbucks vs. Equal Exchange: Assessing the Human Costs of Economic Globalization Lindsey M. Smith This paper discusses the impact of economic globalization on human populations and their natural environment. Trends leading to globalization, such as multilateral and bilateral trade 8fT88ments which reduce trading barriers between countries, are discussed. According to the economic principle of comparative advantage, all countries which specialize in what they can produce most efficiently should benefit equally from fair trade. Developing countries must increasingly rely on cheap labor and low environmental standards to compete for foreign investment and capital in the global economy. Observers argue that the market is not free enough to conect the long-term damage associated with export policies like this. Poverty, misery and social stratification are increasing in many developing countries as a result. A case study of the coffee industry in Latin America provides evidence of the consequences of globalization policies on the most vulnerable populations. -

What Is Fair Trade?

What is Fair Trade? . A system of exchange that honors producers, communities, consumers and the environment. A model for the global economy rooted in people-to-people connections, justice and sustainability. A commitment to building long-term relationships between producers and consumers. A way of life! Fair Trade - Criteria . Paying a fair wage . Giving employees opportunities for advancement . Providing equal employment opportunities for all people, particularly the most disadvantaged . Engaging in environmentally sustainable practices Fair Trade - Criteria . Being open to public accountability . Building sustainable long-term trade relationships . Providing healthy and safe working conditions . Providing financial and technical assistance to producers whenever possible What does the Fair Trade label look like? What does the Fair Trade label mean? Fair Price Democratically organized groups receive a minimum floor price and an additional premium for certified organic agricultural products. Farmer organizations are also eligible for pre-harvest credit. Artisan groups and cooperatives receive a fair living wage for the time it takes to make a product. What does the Fair Trade label mean? Fair Labor Conditions Workers on fair trade farms and other environments enjoy freedom of association, safe working conditions, and living wages. Forced child labor is strictly prohibited. What does the Fair Trade label mean? Direct trade Importers purchase from Fair Trade producer groups as directly as possible, eliminating unnecessary middlepersons and empowering farmers and others to develop the business capacity needed to compete in the global marketplace. What does the Fair Trade label mean? Democratic and transparent organizations Workers decide democratically how to invest Fair Trade revenues. What does the Fair Trade label mean? Environmental Sustainability Harmful agrochemicals and GMOs are strictly prohibited in favor of environmentally sustainable farming methods that protect farmers’ health and preserve valuable ecosystems for future generations. -

Pathways to Just, Equitable and Sustainable Trade and Investment Regimes

Schulich School of Law, Dalhousie University Schulich Law Scholars Reports & Public Policy Documents Faculty Scholarship 7-2021 Pathways to Just, Equitable and Sustainable Trade and Investment Regimes Tomaso Ferrando University of Antwerp, Belgium Nicolas Perrone University of Andres Bello, Chile Olabisi D. Akinkugbe Dalhousie University Schulich School of Law Kangping Du SISU, China Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/reports Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons, Environmental Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Tomaso Ferrando et al, "Pathways to Just, Equitable and Sustainable Trade and Investment Regimes" (Fairtrade Germany and Fairtrade Australia, 2021). This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Schulich Law Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports & Public Policy Documents by an authorized administrator of Schulich Law Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Pathways to Just, Equitable and Sustainable Trade and Investment Regimes Authors: Dr. Tomaso Ferrando (University of Antwerp, Belgium) Dr. Nicolas Perrone (University Andres Bello, Chile) Dr. Olabisi Akinkugbe (Dalhouise University, Canada) Dr. Kangping Du (SISU, China) This study was commissioned by the Fairtrade Germany and Fairtrade Austria. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of these organisations. To get in touch with the authors, please write to Tomaso Ferrando at [email protected]. To get in touch with the commissioning organizations, please write to Peter Möhringer at [email protected] Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3895640 2 Outline Summary of content and recommendations ........................................................................................ -

American University a Sip in the Right Direction: The

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY A SIP IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION: THE DEVELOPMENT OF FAIR TRADE COFFEE AN HONORS CAPSTONE SUBMITTED TO THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM GENERAL UNIVERSITY HONORS BY ALLISON DOOLITTLE WASHINGTON, D.C. APRIL 2009 Copyright © 2009 by Allison Doolittle All rights reserved ii Coffee is more than just a drink. It is about politics, survival, the Earth and the lives of indigenous peoples. Rigoberta Menchu iii CONTENTS ABSTRACT . vi Chapter Page 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 Goals of the Research Background on Fair Trade Coffee 2. LITERATURE REVIEW . 4 The Sociology of Social Movements and Resource Mobilization Fair Trade as a Social Movement Traditional Studies and the Failure to Combine Commodity Chain Analysis with Social Movement Analysis to Study Fair Trade 3. NONGOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF FAIR TRADE . 9 Alternative Trade for Development Alternative Trade for Solidarity Horizontal and Vertical Institution-building within the Movement Roles of Nongovernmental Organizations in Fair Trade Today 4. STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS TO TRANSFORM PUBLICS INTO SYMPATHIZERS . 20 Initial Use of Labels and Narratives to Tell the Fair Trade Story The Silent Salesman: Coffee Packaging that Compels Consumers Fair Trade Advertising, Events and Public Relations Fair Trade and Web 2.0: Dialogue in the Social Media Sphere Internet Use by Coffee Cooperatives to Reach Consumers iv 5. DRINKING COFFEE WITH THE ENEMY: CORPORATE INVOLVEMENT IN FAIR TRADE COFFEE . 33 Market-Driven Corporations: Friend or Foe? Fair Trade as a Corporate Strategy for Appeasing Activists and Building Credibility Fair Trade as a Strategy to Reach Conscious Consumers Internal Debates on Mainstreaming Fair Trade Coffee 6. CONCLUSIONS . -

Co-Operatives and Fair-Trade

KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT LEUVEN Co-operatives and Fair-Trade Background paper commissioned by the Committee for the Promotion and Advancement of Cooperatives (COPAC) for the COPAC Open Forum on Fair Trade and Cooperatives, Berlin (Germany) Patrick Develtere Ignace Pollet February 2005 Higher Institute of Labour HIVA ‐ Higher Institute for Labour Studies Parkstraat 47 3000 Leuven Belgium tel. +32 (0) 16 32 33 33 fax. + 32 (0) 16 32 33 44 www.hiva.be COPAC ‐ Committee for the Promotion and Advancement of Co‐operatives 15, route des Morillons 1218 Geneva Switzerland tel. +41 (0) 22 929 8825 fax. +41 (0) 22 798 4122 www.copacgva.org iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 What is fair-trade? What is co-operative trade? What do both have in common? 2 1. Fair-trade: definition and criteria 2 2. Roots and related concepts 6 3. Actual significance of fair-trade 8 4. Fair-trade and co-operative trade 9 4.1 Where do co-operatives enter the scene? 9 4.2 Defining co-operatives 10 4.3 Comparing co-operative and fair-trade movement: the differences 11 4.4 Comparing the co-operative and fair-trade movement: communalities 13 2. Involvement of co-operatives in practice 14 2.1 In the South: NGOs and producers co-operatives 15 2.2 Co-operatives involved with fair-trade in the North 16 3. Co-operatives and Fair-trade: a fair deal? 19 3.1 Co-operatives for more fair-trade? 19 3.2 Fair-trade for better co-operatives? 20 4. What happens next? Ideas for policy 22 Bibliographical references 25 1 INTRODUCTION This paper is meant to provide a first insight into an apparently new range of activities of the co-operative movement: fair-trade activities. -

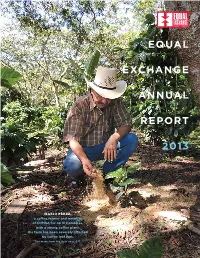

Equal Exchange Annual Report 2013

EQUAL EXCHANGE ANNUAL REPORT 2013 mario pÉrez, a coffee farmer and member of COMSA Co-op in Honduras, with a young coffee plant. His farm has been severely affected by coffee leaf rust. See more from the field on p. 6-7. “WE HAVE BEEN LEADERS IN THIS FIGHT. AND WE HAVE HAD SOME SUCCESSES AND SOME FAILURES. WE HAVE HAD LOTS OF CHALLENGES, BUT YOU WILL NEVER HAVE PROOF OF YOUR SUCCESS IF YOU DON’T TRY.” Margarito Lucas Miguel, below left, a member of Flor del Café Co-op in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala ii From the Office of the Executive Directors Check it Out Through our Charitable Contributions we gave away a portion of pre-tax profits to allied organizations like Fair World Project, Red Tomato, and the InterReligious Task Onwards Force on Central America. & Upwards By Rob Everts & Rink Dickinson, Co-Executive Directors Expansion in products, alliances and geography drove much of our work and increased sales in 2013. On sales of $56.1 million, after charitable contributions and worker-owner patronage disbursements, we realized net income before taxes of $2.7 million. We tried to match the urgent need for markets of small-scale farmers with products that our loyal base of OUR MISSION accounts could competitively offer their customers. Organic To build long-term trade partnerships that are economically just and environmentally sound, cashews from India and El Salvador, organic mangos from to foster mutually beneficial relationships between Burkina Faso, and flame raisins from Chile were among those farmers and consumers and to demonstrate, through our success, that reached store shelves and congregations in 2013. -

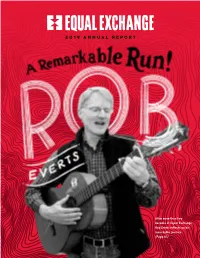

Equal Exchange 2019 Annual Report

2019 ANNUAL REPORT After more than two decades at Equal Exchange, Rob Everts reflects on his remarkable journey. (Page 10) 2019 Sales by Category $1.3 M Other (café, equipment, etc.) $1.6 M EE UK $80.9M Products Total Sales 2019 $2.9 M Tea Food 1986–2019 $5.6 M & Snacks $80M 2016 Action Forum $13.5 M Oké Bananas launched to & Avocados engage customers $70M 2014 and allies as Investment in citizen-consumers Canadian Fair Trade 2004 co-op La Siembra First chocolate 2005 $60M bars launched Begin roasting $14.5 M Chocolate our own coffee & Cocoa $50M 2008 Banana program launched in partnership with $40M Oké USA Sales Growth 1986 Rink Dickinson, $30M Jonathan Rosenthal, and 1999 Michael Rozyne $41.6 M Coffee launch Equal Rink and Rob Exchange Everts take $20M the helm as Co-Executive Directors $10M $0M 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2019 2019 Year OUR MISSION To build long-term trade partnerships that are economically just and environmentally sound, to foster mutually beneficial relationships between farmers and consumers, and to demonstrate, through our success, the contribution of worker cooperatives and fair trade to a more equitable, democratic and sustainable world. 2019 2019 1999 Left: Equal Exchange Co-Executive Directors Rob Everts and Rink Dickinson in 1999. Right: Rink and Rob in 2019. FROM THE OFFICE of the EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS A Season of Change By Rink Dickinson, Co-Executive Director This was a year of organizational change. We dove deep into Foods made a decision in the summer to eliminate all of our staff restructuring, overhauling sales, and product work. -

Fair Trade Backgrounder

Trading Places: Putting the Poor First in Global Relations TEACHER’S RESOURCE FOR FAIR TRADE TABLE OF CONTENTS What is Fair Trade 2 -When did Fair Trade Begin? -Why is Fair Trade Important How to Tell when a Product is Fair Trade 3 Fair Trade in Canada 4 Fair Trade/Non-Fair Trade Supply chain 5 Some Common Fairly Traded Items 8 Words Related to Fair Trade 9 Fair Trade in Action 10 Fair Trade Chocolate Cake Recipe 11 Crossword Puzzle 12 Interesting and Amazing Questions and Facts 13 One Month Challenge 14 Resources 16 Prepared by MCIC, 302-280 Smith Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 1K2 Tel: 204. 987-6420 Fax: 204 956-0031 E-mail: [email protected] PAGE What is fair trade ? Undoubtedly you have heard the term “Fair Trade.” But what, precisely, does the term mean? Basically fair trade means that producers are paid a fair price for the products they produce. But there’s much more involved than just a good price. Fair trade goods are produced in humane working conditions, and factories are monitored for their compliance to minimum standards. By putting control in the hands of producers, fair trade attempts to address structural inequities in the global economy and promote grassroots development. Key elements of fair trade include: Creating opportunities for economically disadvantaged producers Transparency and accountability Promoting independence Payment of a fair price Decent working conditions Sustainable environmental practices No child labour (adapted from www.levelground.com) * Definition of Fair Trade fits into Grade 7 Social Studies Curriculum 7.3.5 KE-049 When did Fair Trade Begin ? The fair trade movement dates back to the late 1940s when US churches began selling handicrafts made by refugees in Europe after World War II. -

Fair Trade: Social Regulation in Global Food Markets

Journal of Rural Studies 28 (2012) 276e287 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Rural Studies journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jrurstud Fair Trade: Social regulation in global food markets Laura T. Raynolds* Center for Fair & Alternative Trade, Sociology Department, Clark Building, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, United States abstract Keywords: This article analyzes the theoretical and empirical parameters of social regulation in contemporary global Regulation food markets, focusing on the rapidly expanding Fair Trade initiative. Fair Trade seeks to transform Globalization North/South relations by fostering ethical consumption, producer empowerment, and certified Fair Trade commodity sales. This initiative joins an array of labor and environmental standard and certification Certification systems which are often conceptualized as “private regulations” since they depend on the voluntary participation of firms. I argue that these new institutional arrangements are better understood as “social regulations” since they operate beyond the traditional bounds of private and public (corporate and state) domains and are animated by individual and collective actors. In the case of Fair Trade, I illuminate how relational and civic values are embedded in economic practices and institutions and how new quality assessments are promoted as much by social movement groups and loosely aligned consumers and producers as they are by market forces. This initiative’s recent commercial success has deepened price competition and buyer control and eroded its traditional peasant base, yet it has simultaneously created new openings for progressive politics. The study reveals the complex and contested nature of social regulation in the global food market as movement efforts move beyond critique to institution building. -

Transfair USA, Annual Report 2009 About Us

Making History TransFair USA, Annual Report 2009 About Us TransFair USA is a nonprofit, mission-driven organization that tackles social and environmental sustainability with an innovative, entrepreneurial approach. We are the leading independent, third-party certifier of Fair Trade products in the United States, and the only U.S. member of Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (FLO). We license companies to display the Fair Trade Certified™ label on products that meet our strict international standards. These standards foster increased social and economic stability, lead- ing to stronger communities and better stewardship of the planet. Our goal is to dramatically improve the livelihoods of farmers, workers and their families around the world. Our Mission TransFair USA enables sustainable development and community empowerment by cultivating a more equitable global trade model that benefits farmers, workers, consumers, industry and the earth. We achieve this mission by certifying and promoting Fair Trade products. Letter from the President & CEO Contents Dear Friends, 04 2009 Accomplishments In 2009, the Fair Trade movement In 2009, we certified over 100 million As we move forward, we have renewed ushered in a new era. Our eleventh year pounds of coffee for the first time, more hope for economic recovery and of certifying Fair Trade products saw than was certified in our first seven continued growth in sales of Fair 06 Fair Trade Certified Apparel social consciousness emerge as a top years of business combined. We saw Trade products. This next phase of priority for consumers, and the numbers opportunities for farm workers broaden Fair Trade is just beginning, and the 08 Social Sustainability reflected it. -

Fair Trade & Equal Exchange

Feature Article Feature FairTrade & Equal Exchange 86 spezzatino.com Volume 8 SO THERE I WAS, STANDING IN THE RAIN IN CHICAGO. THE YEAR WAS 1999, AND I WAS AT YET ANOTHER PROTEST. THIS ONE FairTrade WAS IN FRONT OF STARBUCKS. Yael Grauer & We were demanding that they start carrying Fair Trade coffee. Starbucks qual had hired some guy in a suit to deal with us. Suit immediately swooped in E after our spokesperson was whisked away by television reporters. Then Suit began to spin. He alleged that Starbucks coffee really was fair trade. No dice. I was well-versed on the issue, and could debate the difference between "fair trade" and "certified fair trade". I navigated through his inac- curacies point by factual point. Suit was obviously annoyed. In- deed, he looked downright shocked xchange when our relentless group refused to discuss this inside the store over a E cup of coffee, and continued to stand in the rain with our signs and flyers, petitioning customers to demand that Starbucks carry certified Fair Trade coffee. He seemed to wonder why all these folks were making such a fuss about some beans. PHOTO: "Coffee She Picked", withonef Volume 8 spezzatino.com 87 IN STARK CONTRAST TO THE HORRORS OF THE MAQUILADORAS, THE COFFEE CO-OP OFFERED SOME OF THE MOST EXPLOITED EMPLOYEES A SAFE AND FAIRLY Feature Article Feature PAID PLACE TO WORK. Starbucks eventually relented and whole beans as Café Salvador. We started selling Fair Trade Certified spoke with the workers. The coffee coffee at all its stores beginning in co-op discussions were a stark contrast October 2000.