DOING WELL and DOING GOOD Philanthropy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2010—2011 Health Programs Financial Information Leader in Disease Independent Auditors’ Report

Celebrating 30 years of waging peace, fighting disease, and building hope 30 ANNUAL REPORT 2010—2011 HEALTH PROGRAMS FINANCIAL INFORMATION Leader in Disease Independent Auditors’ Report . 64 Eradication and Elimination . 20 Financial Statements . 65 Partner for Village-Based Notes to Statements . 70 Health Care Delivery . 22 OUR COMMUNITY The Carter Center at a Glance . 2. Voice for Mental Health Care . 24 The Carter Center Around Aontents Message from President Health Year in Review . 26 the World . 84 CJimmy Carter . 3 PHILANTHROPY Senior Staff . 86 Interns . 86 Our Mission . 4 A Message About Our Donors . 32 A Letter from the Officers . 5 International Task Force for Donors with Cumulative Lifetime Disease Eradication . 87 Giving of $1 Million or More . 33 PEACE PROGRAMS Friends of the Inter-American Pioneer of Election Observation . 8 Donors During 2010–2011 . 34 Democratic Charter . 87 Trusted Broker for Peace . 10 Ambassadors Circle . 48 Mental Health Boards . 88 Champion for Human Rights . 12 Legacy Circle . 58 Board of Councilors . 89 Peace Year in Review . 14 Founders . 61 Board of Trustees . 92 A woman works at a small-scale subsistence mine in the province of Katanga, southeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo . The Carter Center’s work in the country is raising awareness about the nation’s lucrative mining industry, which generates huge profits while impoverished local communities receive few of the benefits . 1 The Carter Center at a Glance Overview • Strengthening international standards for human rights The Carter Center was founded in 1982 by former U.S. and the voices of individuals defending those rights in President Jimmy Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, in their communities worldwide partnership with Emory University, to advance peace and • Pioneering new public health approaches to preventing health worldwide. -

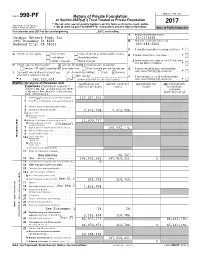

ONFI-2017-990-PF.Pdf

OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 2017 G Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service G Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2017 or tax year beginning , 2017, and ending , A Employer identification number Omidyar Network Fund, Inc 20-1173866 1991 Broadway St #200 B Telephone number (see instructions) Redwood City, CA 94063 650-482-2500 C If exemption application is pending, check here. G G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D1Foreign organizations, check here. G Final return Amended return Address change Name change 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach computation . G H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here. G IJFair market value of all assets at end of year Accounting method: CashX Accrual (from Part II, column (c), line 16) Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination G $ 545,202,008. (Part I, column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here. G Part I Analysis of Revenue and (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net (d) Disbursements Expenses (The total of amounts in expenses per books income income for charitable columns (b), (c), and (d) may not neces- purposes sarily equal the amounts in column (a) (cash basis only) (see instructions).) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc., received (attach schedule). -

Are the Auction Houses Doing All They Should Or Could to Stop Online Fraud?

Federal Communications Law Journal Volume 52 Issue 2 Article 8 3-2000 Online Auction Fraud: Are the Auction Houses Doing All They Should or Could to Stop Online Fraud? James M. Snyder Indiana University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Communications Law Commons, Consumer Protection Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Snyder, James M. (2000) "Online Auction Fraud: Are the Auction Houses Doing All They Should or Could to Stop Online Fraud?," Federal Communications Law Journal: Vol. 52 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj/vol52/iss2/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Federal Communications Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE Online Auction Fraud: Are the Auction Houses Doing All They Should or Could to Stop Online Fraud? James M. Snyder* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 454 II. COMPLAINTS OF ONLINE AUCTION FRAUD INCREASE AS THE PERPETRATORS BECOME MORE CREATV ................................. 455 A. Statistical Evidence of the Increase in Online Auction Fraud.................................................................................... 455 B. Online Auction Fraud:How Does It Happen? ..................... 457 1. Fraud During the Bidding Process .................................. 457 2. Fraud After the Close of the Auction .............................. 458 IlL VARIOUS PARTES ARE ATrEMPTNG TO STOP ONLINE AUCTION FRAUD .......................................................................... 459 A. The Online Auction Houses' Efforts to Self-regulate........... -

Threat from the Right Intensifies

THREAT FROM THE RIGHT INTENSIFIES May 2018 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................1 Meeting the Privatization Players ..............................................................................3 Education Privatization Players .....................................................................................................7 Massachusetts Parents United ...................................................................................................11 Creeping Privatization through Takeover Zone Models .............................................................14 Funding the Privatization Movement ..........................................................................................17 Charter Backers Broaden Support to Embrace Personalized Learning ....................................21 National Donors as Longtime Players in Massachusetts ...........................................................25 The Pioneer Institute ....................................................................................................................29 Profits or Professionals? Tech Products Threaten the Future of Teaching ....... 35 Personalized Profits: The Market Potential of Educational Technology Tools ..........................39 State-Funded Personalized Push in Massachusetts: MAPLE and LearnLaunch ....................40 Who’s Behind the MAPLE/LearnLaunch Collaboration? ...........................................................42 Gates -

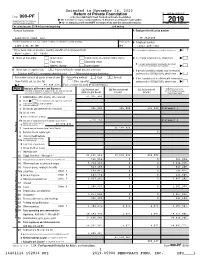

2019 Form 990-PF

Extended to November 16, 2020 Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation | Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury 2019 Internal Revenue Service | Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2019 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer identification number Democracy Fund, Inc. 38-3926408 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number 1200 17th St NW 300 (202) 420-7943 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here ~ | Washington, DC 20036 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ~~ | Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Address change Name change check here and attach computation ~~~~ | X H Check type of organization: Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ~ | X I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part II, col. (c), line 16) Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ~ | | $ 87,348,415. -

A Conversation with Hawai'i's Own Pierre Omidyar Taking the Hawai'i International Confere

Volume 33, Number 1 Spring 2010 INSIDE: Be True to Your School | A Conversation with Hawai‘i’s Own Pierre Omidyar Taking the Hawai‘i International Conference on System Sciences to New Heights DEAn’s MessAGE “We are proud to announce that our undergraduate program has, for the first time, been named as one of the nation’s top business programs by Bloomberg BusinessWeek.” Aloha, Conference on System Sciences into nation’s best by Bloomberg BusinessWeek. The Shidler College of Business one of the world’s leading gatherings on This is truly a credit to our entire faculty is a special place where people of all information systems applications. and staff who have worked tirelessly to cultures and backgrounds come together For those of you who are aspiring strengthen our programs, student services, to share ideas, dreams and business entrepreneurs, be sure to check out the internships and career placement. aspirations. Our global community of excerpts from our exclusive interview It has been a remarkable six months alumni, students, faculty and business with eBay founder Pierre Omidyar. As the and we thank you for sharing an interest professionals lies at the heart of our featured speaker for the Kı¯papa i ke Ala in all that we have accomplished. As success and is what makes this such a Lecture, he inspired us all to dream big. always, we hope that you enjoy this issue unique place to learn, grow and develop. Shidler pride continues to reign of Shidler Business. We welcome your The stories and articles in this issue of strong among our alumni. -

Canopy, Spring 2019 (PDF)

SPRING 2019 ALUMS MAKING A STRONGER, MORE SUSTAINABLE NEW HAVEN Page 16 A Growing Nation A group of F&ES students travels to Rwanda each year with faculty members Bill Weber and Amy Vedder to learn about wildlife conservation, ecotourism, and local culture. Students visit several national parks, including Nyungwe National Park in Rwanda, where sustainable land management practices like terrace farming (seen here) have become more commonplace. andy lee andy IN THIS ISSUE CANOPY Toolkit for an 'Apocalypse' 4 executive editor Keeping It in the Family 6 Matthew Garrett Director of Communications and Web Operations News & Notes 8 editors Kevin Dennehy Research Updates 13 Associate Director of Communications Josh Anusewicz Keeping It Local 16 Assistant Editor art director Out & About 24 Angela Chen-Wolf Design Manager A Post-Coal Future for Appalachia 26 designer Jamie Ficker Making the Invisible Visible 28 editorial advisory board Danielle Dailey, Kristin Floyd, Brad Gentry, Hannah Peragine It Takes a Network 30 Melanie Quigley, Os Schmitz, Karen Seto, and Julie Zimmerman dean In Defense of the Predator 32 Indy Burke Carl W. Knobloch, Jr. Dean Commencement 2019 37 contributors Katie Bleau Parting Thoughts From an F&ES Favorite 42 cover photo Matthew Garrett Class Notes 44 Canopy is published twice a year (spring and fall) by the In Memoriam 59 Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies (F&ES). Editorial offices are located at Bookshelf 60 Sage Hall 205 Prospect Street New Haven, CT 06511 Endnote 61 [email protected] 203-436-4805 Every time you get a new email address, relocate, or change positions, please send us an update at [email protected]. -

SHOULD YOU GIVE THROUGH an LLC? JOHN: Good Morning Everyone

Friday, October 25, 2019, Aviara (T21_1) SHOULD YOU GIVE THROUGH AN LLC? JOHN: Good morning everyone. My name is John Tyler. I’m the general counsel secretary, chief ethics officer for the Ewing Kauffman Foundation and it’s my privilege to be able to moderate and facilitate this session on really philanthropy and use of the LLC model. The Jan Zuckerberg initiative made a big splash a couple of years ago when Mark and Priscilla announced that they were going to set up their philanthropy through an LLC. And there was all sorts of, mostly uproar and a little bit of excitement and quite a bit of misunderstanding in the uproar. But Jan Zuckerberg was not by any means, the first philanthropy to be approached with this structure. But it did ignite interest in the structure and that has continued to this day. And I think that there is some good strong curiosity among high net worth individuals about, is this a good structure for me to operate my philanthropy through. And it’s more of an enterprise structure rather than a foundation single structure. It’s looking more the LLC structure through philanthropy is usually encompasses a variety of things. And so we’ve got high net worth individuals wondering is it a good structure for them. We’ve got foundations and community foundations and DAFs and other funders curious about, well wait a second, can we collaborate, can we do work with these for profit philanthropies and so there are questions about that. And there are just questions then that the sector has more broadly: Is the LLC structure going to hurt the credibility, if you will, of the philanthropic sector because it can get away with all of these things? And we’re going to solve all of those questions here this morning. -

Making a Market: Ebay, Stubhub, and Swaptree

case 1-428-994 December 16, 2009 Making a Market: eBay, StubHub, and Swaptree Introduction In 1995, Pierre Omidyar, the holder of a Bachelor’s degree in Computer Science from Tufts University in Massachusetts was working in Silicon Valley. The internet was just emerging and the financial markets were quite active, as many companies needed funding and eventually went public. Time magazine reported that Omidyar was “...troubled by how imperfectly the financial markets seemed to be operating.” It quoted Omidyar as saying “Institutions and large investors had all the inside information. What I wanted to do was create a marketplace where everyone had access to the same information.”1 As a hobby while working at General Magic, Omidyar created Auction Web. This “free online marketplace”2 was launched on Labor Day of 1995. Omidyar’s first posting for auction was a laser pointer he was about to throw away. It was bought by a collector for $14.83. Initially the service was free to both buyers and sellers, but a $250 per month web hosting fee led Omidyar to impose a fee on sellers, if their listed item sold. As Omidyar commented, “The revenues came in at $500, and I thought ‘This is pretty good.’” When the next month’s revenues came in at $1,000, Omidyar regarded it “as a pretty neat trend.”3 eBay In 1997, Auction Web became known as eBay. In 2009, the company’s website termed eBay “a remarkably efficient market created by connecting individuals who wouldn’t otherwise be connected. It was the world’s first example of online social networking.”4 In an interview in 2004, Jeff Skoll, who worked with Omidyar, reflected back on the founding days: “One of the things that we were most proud of was that there were people who were buying and selling on eBay that substantially improved their lives. -

17898 Hon. Jon C. Porter Hon. James L. Oberstar Hon

17898 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS, Vol. 152, Pt. 13 September 12, 2006 Life and the Home Trust Helping Hands Team million dollars to Tufts University to launch tive digital billboards, featuring a static com- fundraising efforts. She is also a member of the Omidyar-Tufts Microfinance Fund. puter-generated image. the Association for Retarded Citizens, and Mr. Speaker, I am proud to honor Pierre In July, an outdoor advertising company do- and Pam Omidyar for their compassion and nated billboards in the Phoenix area as part of until recently, an important volunteer in the sincere desire to improve the world around Bridges Mentoring Program. Perhaps the most them. Their innovative approach has made a the effort to help police stop serial crimes; au- valuable part of Ms. Schoenborn’s community difference in many lives and I wish them well thorities arrested a suspect in the ‘‘Baseline service services is her dedication to visiting in their continued endeavors. Killer’’ case very recently. In a sense, ‘‘wanted’’ posters are part of the elderly, the ill and the shut-ins. f And so today I rise to recognize Ms. Clair American history, from the days of Jesse Schoenborn for her commitment to the better- TRIBUTE TO THE POWER OF THE James to the ‘‘wanted’’ pictures I saw at the ment of the community and I congratulate Ms. BILLBOARD Post Office growing up in Chisholm, MN. The Schoenborn on her nomination for Member of success story of ‘‘wanted’’ billboards serves to the Year by American Legion Auxiliary Unit HON. JAMES L. OBERSTAR remind us that billboards are a significant me- 278. -

Disruptive Philanthropy: Chan-Zuckerberg, the Limited Liability Company, and the Millionaire Next Door

Florida Law Review Volume 70 Issue 5 Article 1 October 2019 Disruptive Philanthropy: Chan-Zuckerberg, the Limited Liability Company, and the Millionaire Next Door Dana Brakman Reiser Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Dana Brakman Reiser, Disruptive Philanthropy: Chan-Zuckerberg, the Limited Liability Company, and the Millionaire Next Door, 70 Fla. L. Rev. 921 (2019). Available at: https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol70/iss5/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized editor of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reiser: Disruptive Philanthropy: Chan-Zuckerberg, the Limited Liability C DISRUPTIVE PHILANTHROPY: CHAN-ZUCKERBERG, THE LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY, AND THE MILLIONAIRE NEXT DOOR Dana Brakman Reiser* Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Dr. Priscilla Chan, have pledged to give 99% of their net worth to—in their words— “advance[e] human potential and promot[e] equal opportunity.” To make good on this promise, however, they did not set up a traditional nonprofit, tax-exempt organization. Instead, they founded the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative, a limited liability company (LLC). The bulk of this Article provides the definitive explanation for this seemingly bizarre choice. Importantly, the philanthropy LLC structure offers donors the flexibility to bolster charitable grantmaking with impact investment and political advocacy, free of the restrictions, penalties, and transparency requirements applied to tax-exempt vehicles. The LLC form also provides donors complete control over the organizations they found, including an ability to reclaim donated assets that is absolutely prohibited in traditional forms. -

HKS Magazine

HARVARD + CONCERNED CITIZEN KENNEDY WHO ARE YOUR PEOPLE? SCHOOL THE ADVOCATE magazine winter 2020 EARLYBIRD PRICING NOW AVAILABLE! 1_HKSmag_wi20_cvr1-4_F2.indd 3 1/14/20 2:48 PM THE SIXTH COURSE FOR ONE EVENING IN NOVEMBER, the Forum was remade into the White House Situation Room. The imagined scenario: a crisis in 2021 as North Korea fires a test missile far into the Pacific Ocean, with experts convinced this advance in the country’s capabilities was funded by a new Chinese digital currency. The assembled group, which included former Cabinet members and presidential advisers such as Lawrence Summers, Meghan O’Sullivan, and Ash Carter, dove deeply into the substance of the matter. Just as valuable, their firsthand knowledge of how personalities, agendas, and imperfect information play vital roles in decision making. PHOTO BY MIKE DESTEFANO winterwinter 20202020 | harvard kennedy school 1 2 HKSmag_wi20_IFC2-11_F2.indd 2 1/14/20 12:13 PM 2 HKSmag_wi20_IFC2-11_F2.indd 1 1/14/20 12:14 PM EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IN THIS ISSUE WHEN I SPEAK TO PEOPLE ON MY TRAVELS, or to people who are visiting Harvard Kennedy School Associate Dean for from across the United States and around the globe, they often ask me what we are doing to Communications and Public Affairs strengthen democracy and democratic institutions at a time when they appear to be under Thoko Moyo threat. In this issue of the magazine, we offer some answers to that important question. Managing Editor Many of our faculty, students, alumni, and staff are committed to making democracy Nora Delaney count. We have efforts underway to increase civic participation, strengthen democratic Editor institutions, train leaders to be more responsive to their citizens, and improve accuracy in the Robert O’Neill media and the public sphere.