Public Policies for Roma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organization and Management of Female Sports Development in Albania

E-ISSN 2281-4612 Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Vol 5 No 3 ISSN 2281-3993 MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy November 2016 Organization and Management of Female Sports Development in Albania Koci Ledina Sport University of Tirana,Faculty of Movement sciences Depatament of Sports Email:[email protected] Elmazi Rovena Sport University of Tirana,Faculty of Physical Activity and Recreation Departament of Organisation & Menagement; Email:[email protected] Plasa Migena Institute of sport Research,Sports University of Tirana Doi:10.5901/ajis.2016.v5n3p159 Abstract Throughout the transition period Albania faced great challenges to create its future and such transition was very long and difficult. It was a long process of amendments including a comprehensive structural, economic, legal, cultural, and social and sports related package. The designing of reforms and institutions was oriented towards political aims and the quickest reforming occurred in less expensive areas. Such orientation resulted as well in consequences to the development of sports in Albania and female teams in particular. The poor organization of several bodies responsible for the development of sports in our country has led to serious consequences on the progress of female sports. The sports clubs in cooperation with the respective federations must draft special inspection programme to identify talents, promote sports values and cooperation with the teachers of physical education and parents so as to raise awareness and encourage as many girls as possible to become part of sports teams and above all orient them towards the proper discipline. Orientation towards the proper discipline is fundamental and it may be done only by the sports specialists who must see the physical, motor, psychic, anthropometric etc development in order to further assess the discipline to which they may be better aligned with. -

Impact of Importing Foreign Talent on Performance Levels of Local Co-Workers

IMPACT OF IMPORTING FOREIGN TALENT ON PERFORMANCE LEVELS OF LOCAL CO-WORKERS by J. Alvarez (Universidad Complutense), D. Forrest (University of Salford), I. Sanz (Universidad Complutense), and J. D. Tena (Universidad Carlos III)* May, 2008 Abstract- When skilled labour is imported to work in a creative industry, local workers may benefit, in terms of their own level of skill, through contact with new techniques and practices. European basketball offers an opportunity to investigate the reality of this general claim. For a panel of 47 European countries observed over more than twenty years, we model probability of qualification for, and subsequent performance in, Olympic Tournaments and World and European Championships. We demonstrate that an increase in the number of foreigners in a domestic league tends to generate a subsequent improvement in the performance of the national team (which has to be comprised only of local players). Given that foreign players have such a beneficial impact, we develop a theoretical framework for how a regulator of the sports labour market might take this into account. key words: basketball, migration, spillovers. * We acknowledge financial support from the Consejo Superior de Deportes of Spain. IMPACT OF IMPORTING FOREIGN TALENT ON PERFORMANCE LEVELS OF LOCAL CO-WORKERS 1. Motivation In an era of globalisation of labour markets there are few developed countries where the issue of whether immigration brings net benefits to the host economy does not lie at the heart of political debate. In this paper we focus on skilled immigrants. On the one hand, they may boost national output but, on the other, labour unions argue that they depress wages and/ or reduce employment for their members. -

Of Humanities and Social Sciences

European Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences № 6 2020 PREMIER Vienna Publishing 2020 European Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Scientifi c journal № 6 2020 ISSN 2414-2344 Editor-in-chief Maier Erika, Germany, Doctor of Philology Lewicka Jolanta, Poland, Doctor of Psychology International editorial board Massaro Alessandro, Italy, Doctor of Philosophy Marianna A. Balasanian, Georgia, Doctor of Philology Abdulkasimov Ali, Uzbekistan, Doctor of Geography Meymanov Bakyt Katt oevich, Kyrgyzstan, Doctor of Economics Adieva Aynura Abduzhalalovna, Kyrgyzstan, Doctor of Economics Serebryakova Yulia Vadimovna, Russia, Ph.D. of Cultural Science Arabaev Cholponkul Isaevich, Kyrgyzstan, Doctor of Law Shugurov Mark, Russia, Doctor of Philosophical Sciences Barlybaeva Saule Hatiyatovna, Kazakhstan, Doctor of History Suleymanova Rima, Russia, Doctor of History Busch Petra, Austria, Doctor of Economics Fazekas Alajos, Hungary, Doctor of Law Cherniavska Olena, Ukraine, Doctor of Economics Garagonich Vasily Vasilyevich, Ukraine, Doctor of History Proofreading Kristin Th eissen Jansarayeva Rima, Kazakhstan, Doctor of Law Cover design Andreas Vogel Karabalaeva Gulmira, Kyrgyzstan, Doctor of Education Additional design Stephan Friedman Kvinikadze Giorgi, Georgia, Doctor of Geographical Sciences Editorial offi ce Premier Publishing s.r.o. Praha 8 Kiseleva Anna Alexandrovna, Russia, Ph.D. of Political Sciences – Karlín, Lyčkovo nám. 508/7, PSČ 18600 Khoutyz Zaur, Russia, Doctor of Economics Kocherbaeva Aynura Anatolevna, Kyrgyzstan, Doctor of Economics E-mail: [email protected] Konstantinova Slavka, Bulgaria, Doctor of History Homepage: ppublishing.org European Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences is an international, German/English/Russian language, peer-reviewed journal. It is published bimonthly with circulation of 1000 copies. Th e decisive criterion for accepting a manuscript for publication is scientifi c quality. -

Report of the Consultative Visit to Albania 28-29 June 2012 EPAS (2012) 32Rev1

Strasbourg, 28 April 2014 EPAS (2012) 32rev1 ENLARGED PARTIAL AGREEMENT ON SPORT (EPAS) Report of the consultative visit to Albania 28-29 June 2012 EPAS (2012) 32rev1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Auto-evaluation reports by the authorities of Albania..............................................3 - Overview of sports organisations and state structures.................................................3 - Report on the implementation of the European Sport Charter ....................................6 B. Report of the consultative team ...................................................................................9 C. Comments from Albania ............................................................................................26 Appendices: Appendix I Programme of the Council of Europe’s experts’ visit to Albania .......27 Appendix II The Law on Sport in Albania ..............................................................29 2 EPAS (2012) 32rev1 A. Auto-evaluation reports by the authorities of Albania Republic of Albania Ministry of Tourism, Culture, Youth and Sports Overview of sports organisations and state structures Tirana, May 2012 1. Institutional structure The Albanian Law on Sport regulates sport, government institutions working in sport at local and national levels and sports organisations in the public interest. The responsibilities of the Ministry of Tourism, Culture, Youth and Sports of Albania and other actors in the sport field are defined by Article 8 of the amended Albanian Law on Sport (Law No.9376) (see "Official Gazette” -

Albania Calls 2019

© Published on behalf of the Albanian Investment Development Agency, December 2019 (AIDA) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 |COUNTRY PROFILE ...................................................................................pg.5 2 |TOP REASONS TO INVEST IN ALBANIA .................................................pg.8 3 |INVESTMENT AND BUSINESS CLIMATE ..............................................pg.14 4 |FREE TRADE AGREEMENTS ...................................................................pg.18 5 |LEGAL FRAMEWORK ON FOREIGN INVESTMENTS ...........................pg.22 6 |MACROECONOMIC INDICATORS ........................................................pg.28 7 |POTENTIAL INVESTMENT SECTORS .....................................................pg.32 8 |TRAVEL & TOURISM ................................................................................pg.35 9 |MANUFACTURE ......................................................................................pg.39 10 |AGRICULTURE .........................................................................................pg.41 11 |TRANSPORT & LOGISTICS .....................................................................pg.44 12 |BUSINESS PROCESS OUTSORCING ......................................................pg.47 13 |TECHNICAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AREAS TEDA’S......pg.50 14 |ATTRACTIONS..........................................................................................pg.52 15 |TIRANA, THE CAPITAL CITY....................................................................pg.55 MONTENEGRO KOSOVO Bajram -

186/197 Fenerbahce Ulker

teams Aris TT Bank THESSALONIKI - GREECE Official Club Name ARIS BSA 2003 Foundation Year 1914 aving made a successful return to the sive end, although he is also a dangerous spot- Euroleague last year, Aris TT Bank and up shooter. H its one-of-a-kind fans look forward in Mark down Massey as the power player who 2007-08 to taking another step together on the will anchor the frontcourt. Massey had one of road to greatness. Last season, the club's first in the best debut seasons ever in the Euroleague, the Euroleague in more than a decade, saw the ranking second in overall performance rating famed Alexandreio Melathron arena in Thessa- while proving to be both a rebounding and scor- loniki rock as few sports venues on earth can as ing force to be reckoned with. What’s more, Aris challenged the continent's best teams all Massey’s power dunks always get the Aris the way through the Top 16. This season Aris crowd involved in a way that often sways the presents several new faces, starting with head momentum of games. He'll team with the rookie coach Gordon Herbert, who will lead his third Terry, an all-around threat at small forward, to Euroleague club. Herbert will have at his dis- give Aris an athletic inside-outside tandem. An- posal last season's stars, Terrel Castle and Jere- other veteran, smooth-scoring Hanno Mottola, miah Massey, while a band of newcomers mix- brings instant offense near the basket, a valuable es the experience of big men Hanno Mottola commodity. -

Consideration of Reports Submitted by States Parties Under Article 73 of the Convention

United Nations CMW/C/ALB/2 International Convention on the Distr.: General 18 January 2017 Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Original: English English, French and Spanish only Members of Their Families Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 73 of the Convention Second periodic reports of States parties due in 2015 Albania* [Date received: 19 December 2016] * The present document is being issued without formal editing. GE.17-00767(E) CMW/C/ALB/2 I. Introduction 1. The Republic of Albania has acceded to the Convention “On the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families” with Law No.9703, dated 02.04.2007. 2. The Committee reviewed the initial report of Albania (CMW/C/ALB/1) at its 138th and 139th meetings (CMW/C/SR.139 and SR.140), held on 22 and 23 November 2010 and adopted the final observations at its 151st meeting held on 1 December 2010. 3. In the previous report, the Committee welcomed the submission of the Report and the written replies to the list of issues, which enabled the Committee to better understand the implementation of the Convention from the state party. 4. The Committee also welcomed the constructive and fruitful dialogue, with a competent delegation. In this Report, Albania will report on specific issues of the Convention and on previous recommendations of the Committee, for the period 2011-2015. 5. The second national periodic report, submitted under the article 73 of the Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (CMW), was drafted pursuant to the Instructions on the form and content of reports that are to be submitted from the State parties in the period 2011-2015. -

Vjetari Statistikor Për Arsimin, Sportin Dhe Rininë

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION, SPORTS AND YOUTH Rruga e Durrësit, Nr. 23, AL- 1001, Tiranë - SHQIPËRI www.arsimi.gov.al VJETARI STATISTIKOR PËR ARSIMIN, SPORTIN DHE RININË 2015 - 2016 dhe seri kohore STATISTICAL YEARBOOK OF EDUCATION, SPORTS AND YOUTH 2015 - 2016 and timely series 1 Botimi u përgatit nga Sektori i Monitorimit, Jetësimit të Prioriteteve dhe Statistikave në Ministrinë e Arsimit, Sportit dhe Rinisë (MASR). This publication was prepared by the Sector of Monitoring, Priorities and Statistics, at the Ministry of Education, Sports and Youth. © 2017, MASR 2 Përmbajtja Content Hyrje 5 Introduction I. ARSIMI PARAUNIVERSITAR 13 I. PRE-UNIVERSITY EDUCATION • Të dhëna statistikore dhe tregues në arsimin parauniversitar • Statistical data and indicators on pre-university education II. ARSIMI I LARTË 51 II. HIGHER EDUCATION • Të dhëna statistikore dhe tregues në arsimin e lartë • Statistical data and indicators on higher education III.TREGUES KRAHASUES TË ARSIMIT 61 III. COMPARATIVE INDICATORS OF EDUCATION IV. SPORTI 67 IV. SPORTS • Të dhëna statistikore dhe tregues në sport • Statistical data and indicators on sport 3 4 Hyrje Introduction Ministria e Arsimit, Sportit dhe Rinisë ka The Ministry of Education, Sports and Youth për synim të sigurojë sistem arsimor cilësor, aims to ensure qualitative educational system, zhvillim perspektiv të arsimit, respektim të potential development of the education, res- interesave të individit, të komunitetit e të shoqë- pect for the interests of the individual, the co- risë dhe pajisë me njohuritë e nevojshme për mmunity and the society and provide the ne- t’u përballur me kërkesat e ekonomisë së tregut cessary knowledge to meet the demands of the në përputhje me përparësitë kombëtare dhe market economy in compliance with national evropiane. -

Albania Calls 2020

© Published on behalf of the Albanian Investment Development Agency, December 2020 (AIDA) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 |COUNTRY PROFILE ...................................................................................pg.5 2 |TOP REASONS TO INVEST IN ALBANIA .................................................pg.8 3 |INVESTMENT AND BUSINESS CLIMATE ..............................................pg.14 4 |FREE TRADE AGREEMENTS ...................................................................pg.18 5 |LEGAL FRAMEWORK ON FOREIGN INVESTMENTS ...........................pg.22 6 |MACROECONOMIC INDICATORS ........................................................pg.28 7 |POTENTIAL INVESTMENT SECTORS .....................................................pg.32 8 |TRAVEL & TOURISM ................................................................................pg.35 9 |MANUFACTURE ......................................................................................pg.39 10 |AGRICULTURE .........................................................................................pg.41 11 |TRANSPORT & LOGISTICS .....................................................................pg.44 12 |BUSINESS PROCESS OUTSORCING ......................................................pg.47 13 |TECHNICAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AREAS TEDA’S......pg.50 14 |ATTRACTIONS..........................................................................................pg.52 15 |TIRANA, THE CAPITAL CITY....................................................................pg.55 MONTENEGRO KOSOVO Bajram -

Legal Sports Aspects of the Law on Sport in Albania

European Journal of Health & Science in Sports Vinciguerra et al., 2019 Volume 6 Issue 1 Sport Management LEGAL SPORTS ASPECTS OF THE LAW ON SPORT IN ALBANIA Vinciguerra. S1, Shatku2. S, Rossi. A1 1University of Study in Torino, Italy, Department of Law, 2Sports University of Tirana, Albania, Faculty of Physical Activity and Recreation Correspondence: Saimir Shatku, e-mail: [email protected] (Accepted 15 March 2019) Abstract The right to sport in Albania is a relatively late developed right for reasons related to the evolution itself and the organization of the state over the years. The reasons for this phenomenon are mostly related to the fact that the state has played a minimal role in undertaking enterprises and initiatives in the context of its promotion or improvement. Given all the factors that have contributed to the gaps in sports legislation in our country, we note that they have been the determinants of the slow development of all sports activities and consequently of the frequent occurrence of conflicts in most cases from the participants in these activities. Due to the fact that sport is one of the most important rights for the affirmation of the individual as a human being, it enjoys special protection by the legislator, which is defined in the country's basic act as the Constitution, which stipulates that1: “The state, within its constitutional powers and the means at its disposal, aims to supplement private initiative and responsibility with the development of sport and recreational activities”. Based on this provision, we can say that the right to sport is developed primarily by the state, which through its mechanisms plays an essential role in defining long-term policies aimed at promoting and protecting effectively all sporting activities. -

Student Handbook for M.A. in International Relations Cohort 7

University of New York, Tirana Social Sciences Department Student Handbook f o r M.A. in International R e l a t i o n s Cohort 7 2017-2019 November 2017 1 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION & PROGRAM’S ACCREDITATION .................................................... 3 2. CONTACT DETAILS .............................................................................................................. 4 3. PROGRAM DETAILS ............................................................................................................. 5 4. PROGRAM SPECIFICATION ............................................................................................... 6 5. PROGRAM AIMS AND LEARNING OUTCOMES .......................................................... 11 6. COURSE DETAILS ................................................................................................................ 14 7. PERSONAL AND TUTORIAL SUPPORT ARRANGEMENTS ...................................... 19 8. ASSESSMENT ARRANGEMENTS ..................................................................................... 23 9. CODE OF CONDUCT ............................................................................................................ 27 10. POLICIES ON CHEATING AND PLAGIARISM ............................................................ 29 11. QUALITY ASSURANCE AND STUDENT INVOLVEMENT IN QA ............................ 31 13. HEALTH AND SAFETY...................................................................................................... 34 14. STUDENT REPRESENTATION -

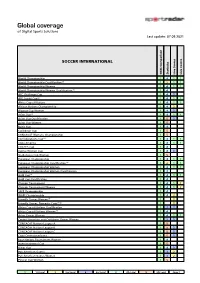

Sportradar Coverage List

Global coverage of Digital Sports Solutions Last update: 07.09.2021 SOCCER INTERNATIONAL Odds Comparison Statistics Live Scores Live Centre World Championship 1 4 1 1 World Championship Qualification (1) 1 2 1 1 World Championship Women 1 4 1 1 World Championship Women Qualification (1) 1 4 AFC Challenge Cup 1 4 3 AFF Suzuki Cup (6) 1 4 1 1 Africa Cup of Nations 1 4 1 1 African Nations Championship 1 4 2 Algarve Cup Women 1 4 3 Asian Cup (6) 1 4 1 1 Asian Cup Qualification 1 5 3 Asian Cup Women 1 5 Baltic Cup 1 4 Caribbean Cup 1 5 CONCACAF Womens Championship 1 5 Confederations Cup (1) 1 4 1 1 Copa America 1 4 1 1 COSAFA Cup 1 4 Cyprus Women Cup 1 4 3 SheBelieves Cup Women 1 5 European Championship 1 4 1 1 European Championship Qualification (1) 1 2 1 1 European Championship Women 1 4 1 1 European Championship Women Qualification 1 4 Gold Cup (6) 1 4 1 1 Gold Cup Qualification 1 4 Olympic Tournament 1 4 1 2 Olympic Tournament Women 1 4 1 2 SAFF Championship 1 4 WAFF Championship 1 4 2 Friendly Games Women (1) 1 2 Friendly Games, Domestic Cups (1) (2) 1 2 Africa Cup of Nations Qualification 1 3 3 Africa Cup of Nations Women (1) 1 4 Asian Games Women 1 4 1 1 Central American and Caribbean Games Women 1 3 3 CONCACAF Nations League A 1 5 CONCACAF Nations League B 1 5 3 CONCACAF Nations League C 1 5 3 Copa Centroamericana 1 5 3 Four Nations Tournament Women 1 4 Intercontinental Cup 1 5 Kings Cup 1 4 3 Pan American Games 1 3 2 Pan American Games Women 1 3 2 Pinatar Cup Women 1 5 1 1st Level 2 2nd Level 3 3rd Level 4 4th Level 5 5th Level Page: