A Focus on Undergraduate Education in the Humanities and Social Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Ispconfig 3 Manual]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9381/ispconfig-3-manual-89381.webp)

Ispconfig 3 Manual]

[ISPConfig 3 Manual] ISPConfig 3 Manual Version 1.0 for ISPConfig 3.0.3 Author: Falko Timme <[email protected]> Last edited 09/30/2010 1 The ISPConfig 3 manual is protected by copyright. No part of the manual may be reproduced, adapted, translated, or made available to a third party in any form by any process (electronic or otherwise) without the written specific consent of projektfarm GmbH. You may keep backup copies of the manual in digital or printed form for your personal use. All rights reserved. This copy was issued to: Thomas CARTER - [email protected] - Date: 2010-11-20 [ISPConfig 3 Manual] ISPConfig 3 is an open source hosting control panel for Linux and is capable of managing multiple servers from one control panel. ISPConfig 3 is licensed under BSD license. Managed Services and Features • Manage one or more servers from one control panel (multiserver management) • Different permission levels (administrators, resellers and clients) + email user level provided by a roundcube plugin for ISPConfig • Httpd (virtual hosts, domain- and IP-based) • FTP, SFTP, SCP • WebDAV • DNS (A, AAAA, ALIAS, CNAME, HINFO, MX, NS, PTR, RP, SRV, TXT records) • POP3, IMAP • Email autoresponder • Server-based mail filtering • Advanced email spamfilter and antivirus filter • MySQL client-databases • Webalizer and/or AWStats statistics • Harddisk quota • Mail quota • Traffic limits and statistics • IP addresses 2 The ISPConfig 3 manual is protected by copyright. No part of the manual may be reproduced, adapted, translated, or made available to a third party in any form by any process (electronic or otherwise) without the written specific consent of projektfarm GmbH. -

Apache Web Server ______

Apache Web Server _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Original author(s) Robert McCool Developer(s) Apache Software Foundation Initial release 1995[1] 2.4.9 (March 17, 2014) [±] Stable release Development Active status Written in C, Forth, XML[2] Type Web server License Apache License 2.0 Website httpd.apache.org The Apache HTTP Server , commonly referred to as Apache , is a web server application notable for playing a key role in the initial growth of the World Wide Web.[3] Originally based on the NCSA HTTPd server, development of Apache began in early 1995 after work on the NCSA code stalled. Apache quickly overtook NCSA HTTPd as the dominant HTTP server, and has remained the most popular HTTP server in use since April 1996. In 2009, it became the first web server software to serve more than 100 million websites.[4] Apache is developed and maintained by an open community of developers under the auspices of the Apache Software Foundation. Most commonly used on a Unix-like system,[5] the software is available for a wide variety of operating systems, including Unix, FreeBSD, Linux, Solaris, Novell NetWare, OS X, Microsoft Windows, OS/2, TPF, OpenVMS and eComStation. Released under the Apache License, Apache is open-source software. As of June 2013, Apache was estimated to serve 54.2% of all active websites and 53.3% of the top servers across all domains.[6][7][8][9][10] 1 Apache Web Server _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Name According to the FAQ in the Apache project website, the name Apache was chosen out of respect to the Native American tribe Apache and its superior skills in warfare and strategy. -

A Requirements-Based Exploration of Open-Source Software Development Projects – Towards a Natural Language Processing Software Analysis Framework

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Computer Information Systems Dissertations Department of Computer Information Systems 8-7-2012 A Requirements-Based Exploration of Open-Source Software Development Projects – Towards a Natural Language Processing Software Analysis Framework Radu Vlas Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cis_diss Recommended Citation Vlas, Radu, "A Requirements-Based Exploration of Open-Source Software Development Projects – Towards a Natural Language Processing Software Analysis Framework." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cis_diss/48 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Computer Information Systems at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Computer Information Systems Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PERMISSION TO BORROW In presenting this dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Georgia State University, I agree that the Library of the University shall make it available for inspection and circulation in accordance with its regulations governing materials of this type. I agree that permission to quote from, to copy from, or publish this dissertation may be granted by the author or, in his/her absence, the professor under whose direction it was written or, in his absence, by the Dean of the Robinson College of Business. Such quoting, copying, or publishing must be solely for the scholarly purposes and does not involve potential financial gain. It is understood that any copying from or publication of this dissertation which involves potential gain will not be allowed without written permission of the author. -

Awstats Logfile Analyzer Documentation

AWStats logfile analyzer 7.4 Documentation Table of contents Release Notes Reference manual What is AWStats / Features Install, Setup and Use AWStats New Features / Changelog Configuration Directives/Options Upgrade Configuration for Extra Sections feature Contribs, plugins and resources Other provided utilities Glossary of terms Other Topics Comparison with other log analyzers FAQ and Troubleshooting Benchmarks AWStats License Plugin Developement AWStats modules for third tools AWStats module for Webmin AWStats module for Dolibarr ERP & CRM Table of contents 1/103 14/07/2015 AWStats logfile analyzer 7.4 Documentation What is AWStats / Features Overview AWStats is short for Advanced Web Statistics. AWStats is powerful log analyzer which creates advanced web, ftp, mail and streaming server statistics reports based on the rich data contained in server logs. Data is graphically presented in easy to read web pages. AWStats development started in 1997 and is still developed today by same author (Laurent Destailleur). However, development is now done on "maintenance fixes" or small new features. Reason is that author spend, since July 2008, most of his time as project leader on another major OpenSource projet called Dolibarr ERP & CRM and works also at full time for TecLib, a french Open Source company. A lot of other developers maintains the software, providing patches, or packages, above all for Linux distributions (fedora, debian, ubuntu...). Designed with flexibility in mind, AWStats can be run through a web browser CGI (common gateway interface) or directly from the operating system command line. Through the use of intermediary data base files, AWStats is able to quickly process large log files, as often desired. -

Download Appendix A

Appendix A Resources Links This list includes most of the URLs referenced in this book. For more online resources and further reading, see our website at http://bwmo.net/ Anti-virus & anti-spyware tools • AdAware, http://www.lavasoftusa.com/software/adaware/ • Clam Antivirus, http://www.clamav.net/ • Spychecker, http://www.spychecker.com/ • xp-antispy, http://www.xp-antispy.de/ Benchmarking tools • Bing, http://www.freenix.fr/freenix/logiciels/bing.html • DSL Reports Speed Test, http://www.dslreports.com/stest • The Global Broadband Speed Test, http://speedtest.net/ • iperf, http://dast.nlanr.net/Projects/Iperf/ • ttcp, http://ftp.arl.mil/ftp/pub/ttcp/ 260! The Future Content filters • AdZapper, http://adzapper.sourceforge.net/ • DansGuard, http://dansguardian.org/ • Squidguard, http://www.squidguard.org/ DNS & email • Amavisd-new, http://www.ijs.si/software/amavisd/ • BaSoMail, http://www.baso.no/ • BIND, http://www.isc.org/sw/bind/ • dnsmasq, http://thekelleys.org.uk/dnsmasq/ • DJBDNS, http://cr.yp.to/djbdns.html • Exim, http://www.exim.org/ • Free backup software, http://free-backup.info/ • Life with qmail, http://www.lifewithqmail.org/ • Macallan Mail Server, http://macallan.club.fr/ • MailEnable, http://www.mailenable.com/ • Pegasus Mail, http://www.pmail.com/ • Postfix, http://www.postfix.org/ • qmail, http://www.qmail.org/ • Sendmail, http://www.sendmail.org/ File exchange tools • DropLoad, http://www.dropload.com/ • FLUFF, http://www.bristol.ac.uk/fluff/ Firewalls • IPCop, http://www.ipcop.org/ • L7-filter, http://l7-filter.sourceforge.net/ -

Diapositiva 1

Scenari di Pericolosità e Danno SPeeD PROJECT - TASK 1.1 Connection of the “Centri Funzionali” of DPC and RC to the monitoring system of INGV-OV G. Scarpato (1), L. D’Auria (1), M. Martini (1), G. Borriello (1), C. Buonocunto (1), M. Capello (1), W. De Cesare (1), A. Esposito (1), F. Giudicepietro (1), D. Lo Bascio (1), M. Orazi (1), R. Peluso(1), P. Ricciolino (1) (1) Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Sezione di Napoli “Osservatorio Vesuviano” Activities Contains: • Project specifications; MySQL Data 1. User Table Base 2. Seismological Table • Server design & realization for the management of the multiparametric data, alarm and notifications provided by 3. Geodedic Table the OV-INGV monitoring system; 4. Geochemical Table • Multiparametric database design & realization for the geophysical and geochemical parameters management; Data Base • Connection of the OV monitoring center and the “centro funzionale multirischio della regione campania” with an intranet protected link (using the present connections to internet of the two centers); • Graphic interfaces (GUI) design for the user access and visualization of the multiparametric data, alarms and <<Server Login>> <<Server After Login>> notifications; 1. CheckLogin 1. Accept Query 2. Start Session • Link of the system to the “Centro Funzionale” DPC (preserving the compatibility with the dpc-ingv 2. Send Request data 3. Send Cookie communications protocols). LAMP Server Realizations • Server system is based on GNU/Linux Operating System – Apache WEB Server. • MySQL 5.0 data base (version InnoDB) , a transactional storage engine with commit, rollback e crash recovery capability. • SQLServer data base (GeOVes) for the supervised Seismic Data; • Perl, PHP or Pyton scripting languages; • Web Interfaced System – Maps powered by Google. -

Presentation By: Lilian Thairu AGENDA

APACHE Presentation by: Lilian Thairu AGENDA Introduction Where to get Apache Versions Licensing Use Features Server & Supporting programs Competitors Market structure Pros & Cons Apache Vs Other servers Presentation by: Lilian Thairu Apache Web Server Introduction Often referred to as simply Apache is a public-domain open source Web server developed by a group of programmers of about 20 volunteers called the Apache Software Group. Apache was born in early 1995, as free Web server software based around NCSA httpd 1.3, which was the most popular Web server as at that time, and with a bunch of software patches. From that it earned it's name, which stands for "A PAtCHY server." Since then, it has been completely re- written, and has become the most popular WWW server on the Internet. Presentation by: Lilian Thairu ........Introduction Apache lends itself particularly well to projects that are heavily Java based. It offers superior handling of the Java Database Connectivity (JDBC) application program interface. The original version was written for UNIX,but there are now versions run under other platforms. Majority of all web servers using Apache are Linux web servers.Presentation by: Lilian Thairu .......Introduction The Apache web server is a program that parses types of hypertext markup language(HTML) and sends it back to you as a human readable web page. It was the first alternative to the Netscape Communications Corporations web server and it has since evolved to rival other Unix Based web servers in terms of functioning and performance. It has played a key role in the initial growth of the WWW and has been the most popular HTTP server on the WWW. -

Tuning Linux OS on IBM System P the POWER of Innovation June 2007

Front cover Tuning Linux OS on System p The POWER of Innovation Linux kernel tuning DB2, WebSphere, and Oracle tuning SystemTap examples Stephen Hochstetler Kraml Liu Andre Metelo Prasanna S Panchamukhi John Zucker ibm.com/redbooks International Technical Support Organization Tuning Linux OS on IBM System p The POWER of Innovation June 2007 SG24-7338-00 Note: Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page ix. First Edition (June 2007) This edition applies to Red Hat Enterprise Linux AS 4 and SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 10. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2007. All rights reserved. Note to U.S. Government Users Restricted Rights -- Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents Notices . ix Trademarks . x Preface . xi The team that wrote this book . xi Become a published author . xiv Comments welcome. xv Chapter 1. Introduction to the book. 1 1.1 Operating an efficient server: four phase . 2 1.2 Performance tuning guidelines . 3 1.3 Using information from the System p Performance Lab . 3 1.4 Linux Technology Center . 5 1.5 Understanding the organization of this book . 5 Chapter 2. IBM System p hardware . 7 2.1 System p advantages . 8 2.1.1 Performance . 8 2.1.2 Scalability . 9 2.1.3 Reliability, availability, and serviceability. 11 2.1.4 Manageability . 13 2.1.5 Virtualization . 14 2.2 System p product line introduction . 15 2.2.1 POWER servers . 16 2.2.2 PowerPC servers and blades . 23 2.2.3 IntelliStation. -

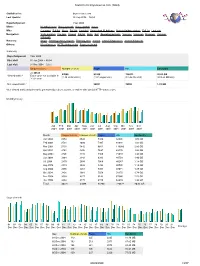

Statistics for Brynosaurus.Com (2004)

Statistics for brynosaurus.com (2004) Statistics for: brynosaurus.com Last Update: 26 Sep 2006 − 03:56 Reported period: Year 2004 When: Monthly history Days of month Days of week Hours Who: Countries Full list Hosts Full list Last visit Unresolved IP Address Robots/Spiders visitors Full list Last visit Navigation: Visits duration File type Viewed Full list Entry Exit Operating Systems Versions Unknown Browsers Versions Unknown Referers: Origin Refering search engines Refering sites Search Search Keyphrases Search Keywords Others: Miscellaneous HTTP Status codes Pages not found Summary Reported period Year 2004 First visit 01 Jan 2004 − 00:04 Last visit 31 Dec 2004 − 23:57 Unique visitors Number of visits Pages Hits Bandwidth <= 40525 47088 85260 726872 20.63 GB Viewed traffic * Exact value not available in (1.16 visits/visitor) (1.81 pages/visit) (15.43 hits/visit) (459.33 KB/visit) 'Year' view Not viewed traffic * 56661 78092 1.91 GB * Not viewed traffic includes traffic generated by robots, worms, or replies with special HTTP status codes. Monthly history Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 Month Unique visitors Number of visits Pages Hits Bandwidth Jan 2004 3254 3542 5336 34926 1.06 GB Feb 2004 3721 4080 7997 68946 1.83 GB Mar 2004 5103 5842 9661 116080 2.89 GB Apr 2004 3761 4306 7697 69176 1.86 GB May 2004 3796 4415 7466 71072 1.96 GB Jun 2004 2664 3143 6283 49758 1.40 GB Jul 2004 2470 2908 5066 40287 1.18 GB Aug 2004 2279 2836 5394 40026 1.14 GB Sep 2004 2955 -

The Unofficial Cpanel Guide

The Unofficial cPanel Tutorial Written By: Mike Bowden Webmaster Stop http://www.webmasterstop.com/ Webmaster Stop has a simple goal, to provide webmasters with a wealth of information and resources that can’t be found anywhere else on the web. We put many hours into developing the content for Webmaster Stop, so that any webmaster can read and understand any information displayed to them. We also have a plethora of articles written by other webmasters. Running a website isn’t a simple job and can become hard at times, that’s why we try to give our users reliable information and resources so they can continue to become better as a webmaster and aid in the growth of their communities. For more webmaster related articles, please visit Webmaster Stop. We’ve got articles written by many other webmasters on many other categories and topics. This tutorial was written by: Mike Bowden The Unofficial cPanel Guide Most of us know what cPanel is and what it’s used for. Many of us don’t however but would like to know more about the program, how it works and what it’s really used for. cPanel is one of the most popular server management programs out on the market today and probable more utilized then any other server management software. Users have migrated to cPanel for the simple fact of how easy it is to use. Almost everything involved within cPanel has an explanation to it, or some form of example. In most cases this would suffice and no other explanation would be needed. -

The Kerf Toolkit for Intrusion Analysis

Dartmouth College Dartmouth Digital Commons Computer Science Technical Reports Computer Science 3-31-2004 The Kerf toolkit for intrusion analysis Javed Aslam Dartmouth College Sergey Bratus Dartmouth College David Kotz Dartmouth College Ron Peterson Dartmouth College Daniela Rus Dartmouth College See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/cs_tr Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Dartmouth Digital Commons Citation Aslam, Javed; Bratus, Sergey; Kotz, David; Peterson, Ron; Rus, Daniela; and Tofel, Brett, "The Kerf toolkit for intrusion analysis" (2004). Computer Science Technical Report TR2004-493. https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/cs_tr/229 This Technical Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Computer Science at Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Computer Science Technical Reports by an authorized administrator of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Javed Aslam, Sergey Bratus, David Kotz, Ron Peterson, Daniela Rus, and Brett Tofel This technical report is available at Dartmouth Digital Commons: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/cs_tr/229 The Kerf toolkit for intrusion analysis Javed Aslam, Sergey Bratus, David Kotz, Ron Peterson, Daniela Rus, and Brett Tofel Department of Computer Science, and the Institute for Security Technology Studies Dartmouth College {jaa, sergey, dfk, rapjr, rus, btofel}@cs.dartmouth.edu Dartmouth College Computer Science Technical Report TR2004-493 March 31, 2004 Abstract nately, today these experts have few tools that help them to automate this process. We consider the problem of intrusion analysis and The goal of the Kerf project1 is to provide an integrated present the Kerf Toolkit, whose purpose is to provide an set of tools that aid system administrators in analyzing the efficient and flexible infrastructure for the analysis of at- nature and extent of an attack and in communicating the tacks. -

Awstats.Sourceforge.Net

http://awstats.sourceforge.net/ AWStats official web site Free real-time logfile analyzer to get advanced statistics (GNU GPL). Receive AWStats release/updates annoucements... Your EMail: Subscribe [What is AWStats] [Demo] [Features] [Downloads] [Documentation / FAQ] [Comparison] [AWStats Project/Development] What is AWStats AWStats is a free powerful and featureful tool that generates advanced web, streaming, ftp or mail server statistics, graphically. This log analyzer works as a CGI or from command line and shows you all possible information your log contains, in few graphical web Private pages. It uses a partial information file to be able to process large log files, often and quickly. It can analyze log files from all major server tools like Apache log files (NCSA combined/XLF/ELF log format or common/CLF log format), WebStar, IIS (W3C log format) and a lot of other Cloud web, proxy, wap, streaming servers, mail servers and some ftp servers. Take a look at this comparison table for an idea on features and differences between most famous statistics tools (AWStats, Analog, Services Webalizer,...). AWStats is a free software distributed under the GNU General Public License. You can have a look at this license chart to know what you can/can't do. www.netapp.com… As AWStats works from the command line but also as a CGI, it can work with all web hosting providers which allow Perl, CGI and log access. Demo / Screenshots You can browse AWStats demo (real-time update feature has been disabled) to see a sample of most important information AWStats shows you... Demo for web server log files Static demo for ftp log files Static demo for mail log files Learn How NetApp® Unbound Cloud Can Manage You can also have a look at some video tutorials provided by Manuals Fountain (some are free).