The IDF in the Second Intifada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking the Two-State Solution

PolicyWatch #1408 : Special Forum Report Rethinking the Two-State Solution Featuring Giora Eiland and Martin Indyk October 3, 2008 On September 23, 2008, Maj. Gen. (Ret.) Giora Eiland and Ambassador Martin Indyk addressed a Policy Forum luncheon at The Washington Institute. General Eiland is former head of the Israeli National Security Council and currently a senior researcher at the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv. Ambassador Indyk directs the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution. The following is a rapporteur’s summary of their remarks. GIORA EILAND Within the Israeli-Palestinian conflict lies a paradox. Although the two-state solution is well known and widely accepted, and although there is international consensus regarding the need for it, little progress has been made to that end. This means that neither side desires the solution nor is willing to take the necessary risks to move forward and come to an agreement. Ultimately, the most the Israeli government can offer the Palestinians -- and survive politically -- is far less than what any Palestinian leadership can accept. As such, there is a gap between the two sides that continues to widen as the years go on. In many aspects, the current situation is worse than it was eight years ago. In 2000, there were three leaders who were both determined and capable of reaching an agreement: U.S. president Bill Clinton, Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak, and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat. That type of leadership is missing today. In addition, while the two sides enjoyed a reasonable level of security, cooperation, and trust in 2000, the subsequent intifada has created a completely different situation on the ground today. -

Palestinian Forces

Center for Strategic and International Studies Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy 1800 K Street, N.W. • Suite 400 • Washington, DC 20006 Phone: 1 (202) 775 -3270 • Fax : 1 (202) 457 -8746 Email: [email protected] Palestinian Forces Palestinian Authority and Militant Forces Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies [email protected] Rough Working Draft: Revised February 9, 2006 Copyright, Anthony H. Cordesman, all rights reserved. May not be reproduced, referenced, quote d, or excerpted without the written permission of the author. Cordesman: Palestinian Forces 2/9/06 Page 2 ROUGH WORKING DRAFT: REVISED FEBRUARY 9, 2006 ................................ ................................ ............ 1 THE MILITARY FORCES OF PALESTINE ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 2 THE OSLO ACCORDS AND THE NEW ISRAELI -PALESTINIAN WAR ................................ ................................ .............. 3 THE DEATH OF ARAFAT AND THE VICTORY OF HAMAS : REDEFINING PALESTINIAN POLITICS AND THE ARAB - ISRAELI MILITARY BALANCE ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .... 4 THE CHANGING STRUCTURE OF PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY FORC ES ................................ ................................ .......... 5 Palestinian Authority Forces During the Peace Process ................................ ................................ ..................... 6 The -

Military Activism and Conservatism During the Intifadas Murat ÜLGÜL* Abstract Introduction

Soldiers and The Use of Force: Military Activism and Conservatism During The Intifadas Murat ÜLGÜL* Abstract Introduction Are soldiers more prone and likely to use force Are soldiers more prone to use force and initiate conflicts than civilians? To bring a and initiate conflicts than civilians? new insight to this question, this article compares The traditional view in the civil- the main arguments of military activism and military relations literature stresses that military conservatism theories on Israeli policies during the First and Second Intifadas. Military professional soldiers are conservative activism argues that soldiers are prone to end in the use of force because soldiers political problems with the use of force mainly are the ones who mainly suffer in war. because of personal and organizational interests Instead, this view says, it is the civilians as well as the effects of a military-mindset. The proponents of military conservatism, on the who initiate wars and conflicts because, other hand, claim that soldiers are conservative without military knowledge, they on the use of force and it is the civilians most underestimate the costs of war while likely offering military measures. Through an overvaluing the benefits of military analysis of qualitative nature, the article finds 1 action. In recent decades, military that soldiers were more conservative in the use of force during the First Intifadas and Oslo conservatism has been challenged by Peace Process while they were more hawkish in a group of scholars who argue that the the Second Intifada. This difference is explained traditional view is based on a limited by enemy conceptions and by the politicization number of cases, mainly civil-military of Israeli officers. -

Good News & Information Sites

Written Testimony of Zionist Organization of America (ZOA) National President Morton A. Klein1 Hearing on: A NEW HORIZON IN U.S.-ISRAEL RELATIONS: FROM AN AMERICAN EMBASSY IN JERUSALEM TO POTENTIAL RECOGNITION OF ISRAELI SOVEREIGNTY OVER THE GOLAN HEIGHTS Before the House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Subcommittee on National Security Tuesday July 17, 2018, 10:00 a.m. Rayburn House Office Building, Room 2154 Chairman Ron DeSantis (R-FL) Ranking Member Stephen Lynch (D-MA) Introduction & Summary Chairman DeSantis, Vice Chairman Russell, Ranking Member Lynch, and Members of the Committee: Thank you for holding this hearing to discuss the potential for American recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights, in furtherance of U.S. national security interests. Israeli sovereignty over the western two-thirds of the Golan Heights is a key bulwark against radical regimes and affiliates that threaten the security and stability of the United States, Israel, the entire Middle East region, and beyond. The Golan Heights consists of strategically-located high ground, that provides Israel with an irreplaceable ability to monitor and take counter-measures against growing threats at and near the Syrian-Israel border. These growing threats include the extremely dangerous hegemonic expansion of the Iranian-Syrian-North Korean axis; and the presence in Syria, close to the Israeli border, of: Iranian Revolutionary Guard and Quds forces; thousands of Iranian-armed Hezbollah fighters; Palestinian Islamic Jihad (another Iranian proxy); Syrian forces; and radical Sunni Islamist groups including the al Nusra Levantine Conquest Front (an incarnation of al Qaeda) and ISIS. The Iranian regime is attempting to build an 800-mile land bridge to the Mediterranean, running through Iraq and Syria. -

The Changing of the Guard in the IDF Giora Eiland

INSS Insight No. 242, February 20, 2011 The Changing of the Guard in the IDF Giora Eiland The much-publicized conflict between the Minister of Defense and the outgoing IDF Chief of Staff, as well as the drama surrounding the appointment of the new Chief of Staff, diverted public attention from the critical question of the state of the IDF today compared to its state four years ago, when Gabi Ashkenazi assumed Israel's highest military post. Five points are particularly noteworthy. First of all, the past four year period has been among the most peaceful the country has ever known. The northern border, the West Bank, and in fact all of Israel’s borders – including the Gaza Strip region since Operation Cast Lead – were calm sectors with few incidents. While it is true that there are external explanations for the calm, there is no doubt that the quality of the IDF’s activity and operational discipline contributed to this state of affairs. Second, by virtually every known parameter, the army’s preparedness has improved dramatically. Reservists are training more, and their training is of better quality. The army has undertaken major re-equipment processes. The frequency of drills and exercises of the upper echelons has increased, and operational plans, some of which were buried deep in the drawer when the Second Lebanon War broke out, have been reformulated and brought up to date so that they are ready for implementation. Third, the IDF’s five year program, "Tefen," is now entering its fourth year. Unlike the past, it is actually progressing according to plan – and to budget. -

MDE 02/02/00 UA 30/00 Fear for Saf ISRAEL

PUBLIC AI Index: MDE 02/02/00 UA 30/00 Fear for safety 8 February 2000 ISRAEL/LEBANONCivilians in Lebanon and northern Israel During the night of 7 February 2000, at least 18 civilians were injured during an attack by the Israel Air Force (IAF) on civilian targets in Lebanon. Amnesty International fears that there may be more indiscriminate attacks on civilians and civilian objects in Lebanon and northern Israel by both the Lebanese armed opposition group Hizbullah, and the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) and its militia ally, the South Lebanon Army (SLA). In the last two weeks Hizbullah and other armed groups in Lebanon have carried out an increasing number of attacks against the IDF, which occupies part of south Lebanon, and the SLA. The deputy head of the SLA, Colonel Akel Hashem, and five Israeli soldiers have been killed. Israel had retaliated by bombing military targets in Lebanon. On the night of 7 February, however, the IAF bombed three power stations in Baalbek, Deir Nbouh, near Tripoli and another in Jamhur, 10 kilometres east of Beirut. According to media reports, the civilian casualties occurred around Baalbek. The IAF also attacked a Hizbullah base in the Bekaa Valley. Hizbullah leaders have recently threatened to attack Israeli civilians in reprisal for Israeli attacks on Lebanese civilians and civilian objects. In a radio interview on 3 February, a Hizbullah member of the Lebanese parliament said: "We would like to remind the enemy that our Katyushas [rockets] are always ready and capable of terrorising [Israel’s] settlers in the same way that the enemy terrorises our people." At a press conference on 8 February, the head of the Operations Directorate of the IDF, Major-General Giora Eiland, said: "We will consider other actions, more elaborate ones, severe ones .. -

Meeting with US Congressional Leaders

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE Claim No. HQ17M02177 QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION MEDIA AND COMMUNICATIONS LIST BETWEEN: MOHAMMED DAHLAN Claimant and (1) M.E.E LIMITED (2) DAVID HEARST Defendants ________________________________ AMENDED DEFENCE OF BOTH DEFENDANTS CPR 16 PD 1.4 SHORT SUMMARY ________________________________ 1. It is denied that the words complained of are actionable, for the following reasons: 1.1. The issues raised by the claim, specifically the lawfulness and propriety of the alleged activities of the Claimant on behalf of the UAE in the conduct of its foreign affairs, are beyond the subject matter jurisdiction of this Court. 1.2. The words complained of are not defamatory of the Claimant as there are no common standards of society generally (either within England and Wales or across the Additional Jurisdictions specified in the Amended Particulars of Claim) by which the alleged activities of the Claimant on behalf of the UAE in the conduct of its foreign affairs can be judged by this Court. 1.3. The words complained of are not defamatory of the Claimant, alternatively have caused no serious harm to his reputation, in light of his pre-existing reputation within the jurisdiction and within the Additional Jurisdictions specified in the Amended Particulars of Claim, which associates him with corruption, torture and human rights abuses, the use of force for political ends and opposing, undermining and supporting the overthrow by force of democratic governments in the Middle East and North Africa on behalf of the UAE. 1.4. The words complained of do not bear the meanings relied on by the Claimant. -

A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Map .................................................................................................................................. i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions of Apartheid and Persecution ................................................................................. -

To Vote Or Not to Vote: Implications of Postponing Palestinian Elections by Ghaith Al-Omari

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 3477 To Vote or Not to Vote: Implications of Postponing Palestinian Elections by Ghaith al-Omari Apr 28, 2021 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Ghaith al-Omari Ghaith al-Omari is a senior fellow in The Washington Institute's Irwin Levy Family Program on the U.S.-Israel Strategic Relationship. Brief Analysis As the risks of holding Palestinian elections come into focus, a Palestinian Authority decision to postpone the elections will increase tensions on the ground while highlighting structural flaws within Fatah and the PA. edia reports and other sources indicate that when Palestinian Authority (PA) president and Fatah leader M Mahmoud Abbas meets with top officials from various factions on April 29, he will call for the postponement of the parliamentary elections set for May 22. This would effectively cancel the elections. Whether he actually formally postpones the elections during the meeting is uncertain. On the one hand, opposition to this move has emerged from significant quarters and may cause him to delay the announcement. On the other hand, the ill- advised election gambit has exposed deep dysfunctions within the Palestinian political system, turning what Abbas may have considered to be a risk-free way for him to renew his legitimacy into something that may threaten the eighty-five-year-old leader’s grip on power. Thus, whether it happens this week or not, a postponement seems extremely likely. A decision to postpone elections has implications. In the short term, priority must be given to preventing any deterioration in security that may be triggered by postponement. -

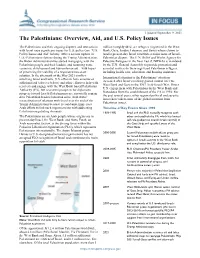

The Palestinians: Overview, 2021 Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues

Updated September 9, 2021 The Palestinians: Overview, Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues The Palestinians and their ongoing disputes and interactions million (roughly 44%) are refugees (registered in the West with Israel raise significant issues for U.S. policy (see “U.S. Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) whose claims to Policy Issues and Aid” below). After a serious rupture in land in present-day Israel constitute a major issue of Israeli- U.S.-Palestinian relations during the Trump Administration, Palestinian dispute. The U.N. Relief and Works Agency for the Biden Administration has started reengaging with the Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is mandated Palestinian people and their leaders, and resuming some by the U.N. General Assembly to provide protection and economic development and humanitarian aid—with hopes essential services to these registered Palestinian refugees, of preserving the viability of a negotiated two-state including health care, education, and housing assistance. solution. In the aftermath of the May 2021 conflict International attention to the Palestinians’ situation involving Israel and Gaza, U.S. officials have announced additional aid (also see below) and other efforts to help with increased after Israel’s military gained control over the West Bank and Gaza in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Direct recovery and engage with the West Bank-based Palestinian U.S. engagement with Palestinians in the West Bank and Authority (PA), but near-term prospects for diplomatic progress toward Israeli-Palestinian peace reportedly remain Gaza dates from the establishment of the PA in 1994. For the past several years, other regional political and security dim. -

Israel's Blockade of Gaza, the Mavi Marmara Incident, and Its Aftermath

Israel’s Blockade of Gaza, the Mavi Marmara Incident, and Its Aftermath Carol Migdalovitz Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs June 23, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41275 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Israel’s Blockade of Gaza, the Mavi Marmara Incident, and Its Aftermath Summary Israel unilaterally withdrew from the Gaza Strip in 2005, but retained control of its borders. Hamas, a U.S. State Department-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO), won the 2006 Palestinian legislative elections and forcibly seized control of the territory in 2007. Israel imposed a tighter blockade of Gaza in response to Hamas’s takeover and tightened the flow of goods and materials into Gaza after its military offensive against Hamas from December 2008 to January 2009. That offensive destroyed much of Gaza’s infrastructure, but Israel has obstructed the delivery of rebuilding materials that it said could also be used to manufacture weapons and for other military purposes. Israel, the U.N., and international non-governmental organizations differ about the severity of the blockade’s effects on the humanitarian situation of Palestinian residents of Gaza. Nonetheless, it is clear that the territory’s economy and people are suffering. In recent years, humanitarian aid groups have sent supply ships and activists to Gaza. However, Israel directs them to its port of Ashdod for inspection before delivery to Gaza. In May 2010, the pro-Palestinian Free Gaza Movement and the pro-Hamas Turkish Humanitarian Relief Fund organized a six-ship flotilla to deliver humanitarian aid to Gaza and to break Israel’s blockade of the territory. -

The IDF in the Second Intifada

Volume 13 | No. 3 | October 2010 A Decade since the Outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Strategic Overview | Michael Milstein The IDF in the Second Intifada | Giora Eiland The Rise and Fall of Suicide Bombings in the Second Intifada | Yoram Schweitzer The Political Process in the Entangled Gordian Knot | Anat Kurz The End of the Second Intifada? | Jonathan Schachter The Second Intifada and Israeli Public Opinion | Yehuda Ben Meir and Olena Bagno-Moldavsky The Disengagement Plan: Vision and Reality | Zaki Shalom Israel’s Coping with the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Critical Review | Ephraim Lavie 2000-2010: An Influential Decade |Oded Eran Resuming the Multilateral Track in a Comprehensive Peace Process | Shlomo Brom and Jeffrey Christiansen The Core Issues of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: The Fifth Element | Shiri Tal-Landman המכון למחקרי ביטחון לאומי THE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL SECURcITY STUDIES INCORPORATING THE JAFFEE bd CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES Strategic ASSESSMENT Volume 13 | No. 3 | October 2010 CONteNts Abstracts | 3 A Decade since the Outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Strategic Overview | 7 Michael Milstein The IDF in the Second Intifada | 27 Giora Eiland The Rise and Fall of Suicide Bombings in the Second Intifada | 39 Yoram Schweitzer The Political Process in the Entangled Gordian Knot | 49 Anat Kurz The End of the Second Intifada? | 63 Jonathan Schachter The Second Intifada and Israeli Public Opinion | 71 Yehuda Ben Meir and Olena Bagno-Moldavsky The Disengagement Plan: Vision and Reality | 85 Zaki Shalom Israel’s Coping with the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Critical Review | 101 Ephraim Lavie 2000-2010: An Influential Decade | 123 Oded Eran Resuming the Multilateral Track in a Comprehensive Peace Process | 133 Shlomo Brom and Jeffrey Christiansen The Core Issues of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: The Fifth Element | 141 Shiri Tal-Landman The purpose of Strategic Assessment is to stimulate and Strategic enrich the public debate on issues that are, or should be, ASSESSMENT on Israel’s national security agenda.