Tax Justice: a Christian Response to a New Gilded Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating Market Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries

Creating Market Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries Creating Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries 2014 About the OECD The OECD is a unique forum where governments work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments and concerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the challenges of an ageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where governments can compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice and work to co-ordinate domestic and international policies. The OECD member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The European Union takes part in the work of the OECD. Since the 1990s, the OECD Task Force for the Implementation of the Environmental Action Programme (the EAP Task Force) has been supporting countries of Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia to reconcile their environment and economic goals. About the EaP GREEN programme The “Greening Economies in the European Union’s Eastern Neighbourhood” (EaP GREEN) programme aims to support the six Eastern Partnership countries to move towards green economy by decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation and resource depletion. The six EaP countries are: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Republic of Moldova and Ukraine. -

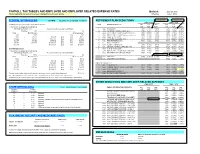

PAYROLL TAX TABLES and EMPLOYEE and EMPLOYER RELATED EXPENSE RATES Updated: June 27, 2012 *Items Highlighted in Yellow Have Been Changed Since the Last Update

PAYROLL TAX TABLES AND EMPLOYEE AND EMPLOYER RELATED EXPENSE RATES Updated: June 27, 2012 *items highlighted in yellow have been changed since the last update. Effective: July 1, 2012 FEDERAL WITHHOLDING 26 PAYS FEDERAL TAX ID NUMBER 86-6004791 RETIREMENT PLAN DEDUCTIONS 10.5% AT 50/50 10.5% AT 50/50 EMPLOYEE EMPLOYER (a) SINGLE person (including head of household) - CODE RETIREMENT PLAN DED OLD NEW DED OLD NEW If the amount of wages (after subtracting CODE RATE RATE CODE RATE RATE withholding allowances) is: The amount of income tax to withhold is: 1 ASRS PLAN-ASRS 7903 11.13% 10.90% 7904 9.87% 10.90% Not Over $83 ............................................................................................. $0 2 CORP JUVENILE CORRECTIONS (501) 7905 8.41% 8.41% 7906 9.92% 12.30% Over But not over - of excess over - 3 EORP ELECTED OFFICIALS & JUDGES (415) 7907 10.00% 11.50% 7908 17.96% 20.87% $83 - $417 10% $83 4 PSRS PUBLIC SAFETY (007) (ER pays 5% EE share) 7909 3.65% 4.55% 7910 38.30% 48.71% $417 - $1,442 $33.40 plus 15% $417 5 PSRS GAME & FISH (035) 7911 8.65% 9.55% 7912 43.35% 50.54% $1,442 - $3,377 $187.15 plus 25% $1,442 6 PSRS AG INVESTIGATORS (151) 7913 8.65% 9.55% 7914 90.08% 136.04% $3,377 - $6,954 $670.90 plus 28% $3,377 7 PSRS FIRE FIGHTERS (119) 7915 8.65% 9.55% 7916 17.76% 20.54% $6,954 - $15,019 $1,672.46 plus 33% $6,954 9 N/A NO RETIREMENT $15,019 ………………………………………………………$4,333.91 plus 35% $15,019 0 CORP CORRECTIONS (500) 7901 8.41% 8.41% 7902 9.15% 11.14% B PSRS LIQUOR CONTROL OFFICER (164) 7923 8.65% 9.55% 7924 38.77% 46.99% (b) MARRIED person F PSRS STATE PARKS (204) 7931 8.65% 9.55% 7932 18.50% 25.16% If the amount of wages (after subtracting G CORP PUBLIC SAFETY DISPATCHERS (563) 7933 7.96% 7.96% 7934 7.50% 7.90% withholding allowances) is: The amount of income tax to withhold is: H PSRS DEFERRED RET OPTION (DROP) 7957 8.65% 9.55% 0.24% AT 50/50 Not Over $312 ............................................................................................ -

Tax Us If You Can 2012 FINAL.Pdf

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Murphy, R. and Christensen, J.F. (2012). Tax us if you can. Chesham, UK: Tax Justice Network. This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16543/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] tax us nd if you can 2Edition INTRODUCTION TO THE TAX JUSTICE NETWORK The Tax Justice Network (TJN) brings together charities, non-governmental organisations, trade unions, social movements, churches and individuals with common interest in working for international tax co-operation and against tax avoidance, tax evasion and tax competition. What we share is our commitment to reducing poverty and inequality and enhancing the well being of the least well off around the world. In an era of globalisation, TJN is committed to a socially just, democratic and progressive system of taxation. -

Can My Church Benefit from a CARES Act Forgivable Loan?

I hope this finds you well and living confidently into the times. Congress passed and the President signed the CARES Act this past Friday, March 27, 2020. I write to share specific information from the CARES Act that answers some of the questions that I have heard being asked. Can my church benefit from a CARES Act forgivable loan? This question is on the minds of most pastors and church leaders since the passage of the $2 trillion relief package. As I continue to participate in some and receive information from other webcasts and conference calls across the connection, there are some things you can begin to do to prepare to apply for the loan program. While I do not encourage you to borrow funds for normal operating expenses, it appears that this loan has the potential to become a grant that you would not need to repay. Attorneys and accountants are studying the bill and awaiting guidelines from the Small Business Administration (SBA) and the U.S. Treasury on how the CARES Act will be administered. However, it appears that churches and non-profits may be able to borrow money that could be completely forgiven if they maintain their previous 12-month staffing levels through June of 2020. Key Provisions: • Paycheck Protection Program (“PPP”) - Eligible churches and non-profits will be able to borrow up to 2.5 times their average monthly payroll and benefits up to $100,000. While this appears to cap the amount to approximately $40,000 of monthly current costs, it is not yet known if that is for all employees in the salary-paying entity or per person. -

Curacao Highlights 2020

International Tax Curaçao Highlights 2020 Updated January 2020 Recent developments: For the latest tax developments relating to Curaçao, see Deloitte tax@hand. Investment basics: Currency – Netherlands Antilles Guilder (ANG) Foreign exchange control – A 1% license fee will be calculated as a percentage of the gross outflow of money on transfers from residents to nonresidents, and on foreign currency cash transactions. Holding companies may obtain an exemption from the fee. Accounting principles/financial statements – IAS/IFRS applies. Financial statements must be prepared annually. Principal business entities – These are the public and private company (NV and BV), general partnership, (private) foundation, Curaçao trust, limited partnership, and branch of a foreign corporation. Corporate taxation: Rates Corporate income tax rate 22%/3%/0% Branch tax rate 22%/3%/0% Capital gains tax rate 22%/3%/0% Residence – A corporation is resident if it is incorporated under the laws of Curaçao or managed and controlled in Curaçao. Basis – In principle, residents are taxed on worldwide income. Exemptions may apply for profits derived by permanent establishments located abroad. In addition, as from 1 July 2018, foreign-source income is excluded from the profit tax base (although there is an exception for certain services, including insurance and reinsurance activities; trust activities; the services of notaries, lawyers, public accountants and tax consultants; related services; income derived from the exploitation of intellectual property (IP); and shipping activities). Page 1 of 7 Curaçao Highlights 2020 Nonresidents are taxed only on Curaçao-source income. Foreign-source income derived by residents that is not excluded from the profit tax base is subject to corporation tax in the same way as Curaçao-source income. -

Die Leiden Des Steuerlichen Wertes

Die Leiden des steuerlichen Wertes Introduction to German Tax Translation Introduction • Basis for taxation in Germany • Major legislative acts • Overview to major tax types • Recent changes to tax law • Resources Basis of Taxation • Grundgesetz (Basic Law) • Abgabenordung, “AO” (General Tax Code) • Finanzgerichtsordnung (Tax Court Procedural Code) Finanzverwaltungsgesetz (Financial/Fiscal Administration Act) Bewertungsgesetz (Valuation Act) • Establishes uniform rules on tax valuation • Applicable to all federal taxes and levies • Defines several common terms, e.g. – gemeiner Wert – Teilwert – Steuerbilanzwert – Einheitswert Major Tax Types • Direct versus indirect • Purpose – Revenue – Repricing (“social” taxes to affect demand) – Redistribution • Taxing (receiving) authority Major Legislation • Einkommensteuergesetz (Personal Income Tax Act) • Körperschaftsteuergesetz (Corporate Income Tax Act) • Umsatzsteuergesetz (Value Added Tax (VAT) Act • Gewerbesteuergesetz (Municipal Trade Tax Act) • Jahressteuergesetz (Annual Tax Act) • Erbschaftsteuergesetz (Inheritance Tax Act) • Grunderwerbsteuergesetz (Real Property Acquisition Tax Act) • Grundsteuergesetz (Real Property Tax Act) • Umwandlungssteuergesetz (Reorganization Tax Act) Tax Revenues in Germany Steuerart Tax Type 2007 revenues Percentage in € bn. 2007 Steueraufkommen Tax revenue 493.818 100.00% insgesamt in Deutschland Total in Germany Gemeinschaftliche Steuern Joint taxes 381.309 77.22% Payroll withholding Lohnsteuer und andere and other personal Einkommensteuern income taxes Direct -

Worksheet Solutions

Worksheet Solutions The Effect of Taxes Theme 4: What Is Taxed and Why Lesson 2: Taxes in a Market Economy Key Term market economy—An economic system based on private enterprise that rests upon three basic freedoms: freedom of the consumer to choose among competing products and services, freedom of the producer to start or expand a business, and freedom of the worker to choose a job and employer. Summary Although the United States has a market economy, the government still plays an important role in business and financial affairs. In fact, about one-third of the nation’s economy is based on government spending. For the most part, the government does not have an income of its own. At all levels the government relies on tax revenue to fund most of the services it provides and to purchase goods and services from others. Tax revenue is dependent on what individuals and businesses earn, spend, and own. Activity 1 Answer the following multiple-choice questions by writing the letter of the correct answer in the space provided. A 1. With the money Erin earned baby-sitting, she bought a book priced at $5.95. She paid a tax of $.36 on the book. What type of tax did she pay? A. sales tax B. excise tax C. payroll tax D. income tax E. property tax D 2. Mr. Presutti paid taxes on the profits of his construction business. What type of tax did he pay? A. sales tax B. excise tax C. payroll tax D. income tax E. property tax B 3. -

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Top Incomes in Germany, 1871-2014

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11838 Top Incomes in Germany, 1871-2014 Charlotte Bartels SEPTEMBER 2018 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11838 Top Incomes in Germany, 1871-2014 Charlotte Bartels DIW Berlin, UCFS and IZA SEPTEMBER 2018 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 11838 SEPTEMBER 2018 ABSTRACT Top Incomes in Germany, 1871-2014* This study provides new evidence on top income shares in Germany from the period of industrialization to the present. Income concentration was high in the nineteenth century, dropped sharply after World War I and during the hyperinflation years of the 1920s, and increased rapidly throughout the Nazi period beginning in the 1930s. -

Payroll Taxes, Mythology and Fairness Linda Sugin Fordham University, [email protected]

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 2014 Payroll Taxes, Mythology and Fairness Linda Sugin Fordham University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation Linda Sugin, Payroll Taxes, Mythology and Fairness, 51 Harv. J. on Legis 113 (2014) Available at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/508 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\H\HLL\51-1\HLL104.txt unknown Seq: 1 30-JAN-14 8:28 SYMPOSIUM: CLASS IN AMERICA PAYROLL TAXES, MYTHOLOGY, AND FAIRNESS LINDA SUGIN* As the 2012 fiscal cliff approached, Congress and President Obama bick- ered over the top marginal income tax rate that would apply to a tiny sliver of the population, while allowing payroll taxes to quietly rise for all working Amer- icans. Though most Americans pay more payroll tax than income tax, academic and public debates rarely mention it. The combined effect of the payroll tax and the income tax produce dramatically heavier tax liabilities on labor compared to capital, producing substantial horizontal and vertical inequity in the tax system. This article argues that a fair tax system demands just overall burdens, and that the current combination of income taxes and payroll taxes imposes too heavy a relative burden on wage earners. -

Green Tax Reform in Australia in the Presence of Improved Environment-Induced Productivity Gain: Does It Offer Sustainable Recovery from a Post-COVID-19 Recession?

sustainability Article Green Tax Reform in Australia in the Presence of Improved Environment-Induced Productivity Gain: Does It Offer Sustainable Recovery from a Post-COVID-19 Recession? Maruf Rahman Maxim * and Kerstin K. Zander Northern Institute, Charles Darwin University, Casuarina, NT 0810, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 July 2020; Accepted: 10 August 2020; Published: 12 August 2020 Abstract: Disasters and pandemics such as COVID-19 will change the world in many ways and the road to redemption from the ongoing economic distress may require a novel approach. This paper proposes a path towards economic recovery that keeps sustainability at the forefront. A computable general equilibrium model is used to simulate different green tax reform (GTR) policies for triple dividend (TD), consisting of lower emissions, higher GDP and higher employment. The GTR design consists of an energy tax coupled with one of three tax revenue recycle methods: (i) reduction of payroll tax, (ii) reduction of goods and services tax (GST) and (iii) a mixed-recycling approach. The paper also presents the impact of higher productivity on the tax reform simulations, which is a possible positive externality of lower emissions. The study is based on the Australian economy and the salient findings are twofold: (i) productivity gain in the GTR context improves the GDP and employment outcomes in all three different simulation scenarios and (ii) GST reduction has the highest TD potential, followed by reduction of payroll tax. Keywords: green tax reform; CGE modelling; triple dividend; energy tax; positive externality JEL Classification: H23; C68; O44; Q48; D62 1. -

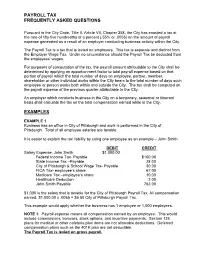

Payroll Tax Frequently Asked Questions Examples

PAYROLL TAX FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS Pursuant to the City Code, Title II, Article VII, Chapter 258, the City has enacted a tax at the rate of fifty-five hundredths of a percent (.55% or .0055) on the amount of payroll expense generated as a result of an employer conducting business activity within the City. The Payroll Tax is a tax that is levied on employers. This tax is separate and distinct from the Employer Wage Tax. Under no circumstance should the Payroll Tax be deducted from the employees’ wages. For purposes of computation of the tax, the payroll amount attributable to the City shall be determined by applying an apportionment factor to total payroll expense based on that portion of payroll which the total number of days an employee, partner, member, shareholder or other individual works within the City bears to the total number of days such employee or person works both within and outside the City. The tax shall be computed on the payroll expense of the previous quarter attributable to the City. An employer which conducts business in the City on a temporary, seasonal or itinerant basis shall calculate the tax on the total compensation earned while in the City. EXAMPLES EXAMPLE 1 Business has an office in City of Pittsburgh and work is performed in the City of Pittsburgh. Total of all employee salaries are taxable. It is easier to explain the tax liability by using one employee as an example – John Smith. DEBIT CREDIT Salary Expense; John Smith $1,000.00 Federal Income Tax- Payable $100.00 State Income Tax –Payable 28.00 City of Pittsburgh & School Wage Tax- Payable 30.00 FICA Tax- employee’s share 67.00 Medicare Tax –employee’s share 10.00 Healthcare Deduction 2.00 John Smith Payable 763.00 $1,000 is the salary that is taxable for the City of Pittsburgh Payroll Tax. -

Reforming Our Tax System, Reducing Our Deficit

ASSOCIATED PRESS/J. S PRESS/J. ASSOCIATED cott A PP L E WH ITE Reforming Our Tax System, Reducing Our Deficit Roger Altman, William Daley, John Podesta, Robert Rubin, Leslie Samuels, Lawrence Summers, Neera Tanden, and Antonio Weiss with Michael Ettlinger, Seth Hanlon, Michael Linden December 2012 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Reforming Our Tax System, Reducing Our Deficit Roger Altman, William Daley, John Podesta, Robert Rubin, Leslie Samuels, Lawrence Summers, Neera Tanden, and Antonio Weiss with Michael Ettlinger, Seth Hanlon, Michael Linden December 2012 Note from the authors: As in any collaborative process, there has been much give and take among the participants in developing this final product. We all subscribe to the analysis and principles articulated here, to the need for revenue levels at the level proposed, and to the need for spending reductions. We also generally agree with the provisions of the plan. There may be specific matters, however, on which some of us have different views. Contents 1 Introduction and summary 5 On the need for more revenue 6 Why the additional revenue must come from high-income households 9 A progressive tax reform 11 Tax rates 12 Cleaning up the tax code 15 Simplifying filing 16 Other taxes 17 The spending side of the equation 20 Bottom line 22 About the authors 24 Acknowledgements 25 Endnotes Introduction and summary There are very few things everyone in Washington can agree on these days. But the one notion that will get heads nodding across the political spectrum is that today’s fiscal policies simply are not sustainable. If we keep doing what we’ve been doing, not only will the federal budget stay permanently deep in the red but critical public investments such as education and infrastructure will continue to go underfunded.