DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Top Incomes in Germany, 1871-2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating Market Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries

Creating Market Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries Creating Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries 2014 About the OECD The OECD is a unique forum where governments work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments and concerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the challenges of an ageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where governments can compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice and work to co-ordinate domestic and international policies. The OECD member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The European Union takes part in the work of the OECD. Since the 1990s, the OECD Task Force for the Implementation of the Environmental Action Programme (the EAP Task Force) has been supporting countries of Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia to reconcile their environment and economic goals. About the EaP GREEN programme The “Greening Economies in the European Union’s Eastern Neighbourhood” (EaP GREEN) programme aims to support the six Eastern Partnership countries to move towards green economy by decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation and resource depletion. The six EaP countries are: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Republic of Moldova and Ukraine. -

Etix VVK Stellen

Altenburg Ticketgalerie GmbH Kornmarkt 1 D-04600 Bad Brückenau Mediengruppe Oberfranken Ludwigstraße 12 D-97769 Bad Kissingen Mediengruppe Oberfranken Theresienstr. 21 D-97688 Bad König Reisebüro Reisefenster Bahnhofstraß 12 D-64732 Bad Langensalza KTL Kur und Tourismus Bad Langensalza GmbH Bei der Marktkirche D-99947 Bad Liebenwerda Reisebüro Jaich Rossmarkt 5 D-04924 Bad Liebenwerda Wochenkurier Markt 16 D-04924 Bad Mergentheim Fränkische Nachrichten Verlags GmbH Kapuzinerstraße 4 (am Schloss) D-97980 Bad Salzungen Abokarten Verwaltungs GmbH BT Andreasstr. 11 D-36433 Bamberg bvd Kartenservice Lange Str. 39/41 D-96047 Bamberg Kartenkiosk Bamberg Forchheimer Str. 15 D-96050 Bamberg Mediengruppe Oberfranken Hauptwachstr. 22 D-96047 Bamberg Mediengruppe Oberfranken Gutenbergstr. 1 D-96050 Bamberg Mediengruppe Oberfranken Gutenbergstraße 1 D-96050 Bautzen Intersport Goschwitzstraße 2 D-02625 Bautzen SZ Bautzen Lauengraben 18 D-02625 Bautzen Wochenkurier Hauptmarkt 7 D-02625 Bayreuth Abokarten Verwaltungs GmbH BT - Nordbayerischer Kurier Theodor-Schmidt-Str. 17 D-95448 Bayreuth Theaterkasse Bayreuth Opernstraße 22 D-95444 Berlin Berliner KartenKontor im Forum Steglitz Schloßstr.1 D-12163 Berlin HOLIDAY LAND Reisebüro & Theaterkasse Schnellerstrasse 21 D-12439 Berlin Reisestudio Menzer Treskowallee 86 D-10318 Bitterfeld Reisebüro Bier Brehnaer Straße 34 D-06749 Borna Ticketgalerie GmbH Brauhausstraße 3 D-04552 Bremen Bremer KartenKontor bei Saturn in der Galeria Kaufhof Papenstr. 5 D-28195 Bremen Bremer Kartenkontor Zum Alten Speicher 9 D-28759 -

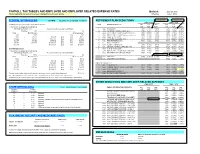

PAYROLL TAX TABLES and EMPLOYEE and EMPLOYER RELATED EXPENSE RATES Updated: June 27, 2012 *Items Highlighted in Yellow Have Been Changed Since the Last Update

PAYROLL TAX TABLES AND EMPLOYEE AND EMPLOYER RELATED EXPENSE RATES Updated: June 27, 2012 *items highlighted in yellow have been changed since the last update. Effective: July 1, 2012 FEDERAL WITHHOLDING 26 PAYS FEDERAL TAX ID NUMBER 86-6004791 RETIREMENT PLAN DEDUCTIONS 10.5% AT 50/50 10.5% AT 50/50 EMPLOYEE EMPLOYER (a) SINGLE person (including head of household) - CODE RETIREMENT PLAN DED OLD NEW DED OLD NEW If the amount of wages (after subtracting CODE RATE RATE CODE RATE RATE withholding allowances) is: The amount of income tax to withhold is: 1 ASRS PLAN-ASRS 7903 11.13% 10.90% 7904 9.87% 10.90% Not Over $83 ............................................................................................. $0 2 CORP JUVENILE CORRECTIONS (501) 7905 8.41% 8.41% 7906 9.92% 12.30% Over But not over - of excess over - 3 EORP ELECTED OFFICIALS & JUDGES (415) 7907 10.00% 11.50% 7908 17.96% 20.87% $83 - $417 10% $83 4 PSRS PUBLIC SAFETY (007) (ER pays 5% EE share) 7909 3.65% 4.55% 7910 38.30% 48.71% $417 - $1,442 $33.40 plus 15% $417 5 PSRS GAME & FISH (035) 7911 8.65% 9.55% 7912 43.35% 50.54% $1,442 - $3,377 $187.15 plus 25% $1,442 6 PSRS AG INVESTIGATORS (151) 7913 8.65% 9.55% 7914 90.08% 136.04% $3,377 - $6,954 $670.90 plus 28% $3,377 7 PSRS FIRE FIGHTERS (119) 7915 8.65% 9.55% 7916 17.76% 20.54% $6,954 - $15,019 $1,672.46 plus 33% $6,954 9 N/A NO RETIREMENT $15,019 ………………………………………………………$4,333.91 plus 35% $15,019 0 CORP CORRECTIONS (500) 7901 8.41% 8.41% 7902 9.15% 11.14% B PSRS LIQUOR CONTROL OFFICER (164) 7923 8.65% 9.55% 7924 38.77% 46.99% (b) MARRIED person F PSRS STATE PARKS (204) 7931 8.65% 9.55% 7932 18.50% 25.16% If the amount of wages (after subtracting G CORP PUBLIC SAFETY DISPATCHERS (563) 7933 7.96% 7.96% 7934 7.50% 7.90% withholding allowances) is: The amount of income tax to withhold is: H PSRS DEFERRED RET OPTION (DROP) 7957 8.65% 9.55% 0.24% AT 50/50 Not Over $312 ............................................................................................ -

The New 39% Tax Rate: What Happens Now?

Tax Tips Alert | 3 December 2020 The new 39% tax rate: what happens now? On Wednesday afternoon, the Government introduced a new tax bill to Parliament under urgency, which proposes a 39% tax rate on individual income over $180,000. Given Labour’s majority in Parliament, the bill is almost With the new income tax rate, many other changes guaranteed to be passed and will be effective for the need to be made to tax legislation. This will ensure start of the 2022 income tax year. the new rate does not create distortions across the taxation of other types of personal income. The other This new rate could form part of New Zealand’s rate changes are to the: progressive tax system for years to come as the Government navigates an economic recovery, • Fringe benefit tax: The rate on amounts of commitments to public services, and budgets to service all inclusive pay over $129,681 will be 63.93% the forecast growth in Government debt. The last top to ensure consistent treatment of cash and marginal rate change was on 1 October 2010, when the non‑cash remuneration. This threshold differs from Government reduced the rate from 38% on income over the income tax threshold because it is calculated $70,000 to 33%, where it has remained since. on the after‑tax value of non‑monetary benefit i.e. taking into account PAYE which would otherwise The 2010 change harmonised the top personal rate have been paid. with the trustee rate. As those rates once again diverge, we expect to see more housekeeping and restructuring • Employer’s superannuation contribution tax and activity in advance of 1 April 2021. -

Tax Us If You Can 2012 FINAL.Pdf

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Murphy, R. and Christensen, J.F. (2012). Tax us if you can. Chesham, UK: Tax Justice Network. This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16543/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] tax us nd if you can 2Edition INTRODUCTION TO THE TAX JUSTICE NETWORK The Tax Justice Network (TJN) brings together charities, non-governmental organisations, trade unions, social movements, churches and individuals with common interest in working for international tax co-operation and against tax avoidance, tax evasion and tax competition. What we share is our commitment to reducing poverty and inequality and enhancing the well being of the least well off around the world. In an era of globalisation, TJN is committed to a socially just, democratic and progressive system of taxation. -

How Britain Unified Germany: Geography and the Rise of Prussia

— Early draft. Please do not quote, cite, or redistribute without written permission of the authors. — How Britain Unified Germany: Geography and the Rise of Prussia After 1815∗ Thilo R. Huningy and Nikolaus Wolfz Abstract We analyze the formation oft he German Zollverein as an example how geography can shape institutional change. We show how the redrawing of the European map at the Congress of Vienna—notably Prussia’s control over the Rhineland and Westphalia—affected the incentives for policymakers to cooperate. The new borders were not endogenous. They were at odds with the strategy of Prussia, but followed from Britain’s intervention at Vienna regarding the Polish-Saxon question. For many small German states, the resulting borders changed the trade-off between the benefits from cooperation with Prussia and the costs of losing political control. Based on GIS data on Central Europe for 1818–1854 we estimate a simple model of the incentives to join an existing customs union. The model can explain the sequence of states joining the Prussian Zollverein extremely well. Moreover we run a counterfactual exercise: if Prussia would have succeeded with her strategy to gain the entire Kingdom of Saxony instead of the western provinces, the Zollverein would not have formed. We conclude that geography can shape institutional change. To put it different, as collateral damage to her intervention at Vienna,”’Britain unified Germany”’. JEL Codes: C31, F13, N73 ∗We would like to thank Robert C. Allen, Nicholas Crafts, Theresa Gutberlet, Theocharis N. Grigoriadis, Ulas Karakoc, Daniel Kreßner, Stelios Michalopoulos, Klaus Desmet, Florian Ploeckl, Kevin H. -

Betreuungsangebote - Nach § 45A (1) Nr

Angebote zur Unterstützung im Alltag - Betreuungsangebote - nach § 45a (1) Nr. 1 SGB XI Landkreis Ort Institution Strasse PLZ E-Mail Telefon Altenburger Land Altenburg AWO KV Altenburger Land e.V. "Selbständiges Humboldtstraße 12 04600 selbst.wohnen.abg@awo- 03447/558998 Wohnen im Alter" thueringen.de Altenburger Land Altenburg Gemeinschaftspraxis für Ergotherapie Katrin Jenke Gabelentzstr. 6c 04600 [email protected] 03447/895464 & Kati Kratzsch Altenburger Land Altenburg Horizonte Altenburg gGmbH Carl von Ossietzky Str. 04600 verwaltung@horizonte- 03447/514212 19 altenburg.de Altenburger Land Rositz Familienentlastender und unterstützender Dienst Parkstr. 1 4617 [email protected] 034498/819263 der Lebenshilfe Altenburg Eichsfeld Heiligenstadt Kath. Altenheime Eichsfeld gGmbH Hospitalstraße 1 37308 [email protected] 03606/661445 Eichsfeld Leinefelde - Lebenshilfe Worbis e.V. Ernemannstr. 6 37327 m.toepfer@lebenshilfe- 03605/200993 Worbis worbis.de Eichsfeld Marth Betreuungsdienst "Mit Freude am Leben" Am Anger 1 37318 betreuungsdienst- [email protected] 036081/61325 Erfurt Erfurt Schutzbund der Senioren und Vorrhuheständler Juri-Gagarin-Ring 64 99084 landesverband@seniorenschut 0361/2620735 Thüringen e.V. zbund.org Erfurt Erfurt Volkssolidarität Thüringen gGmbH Sozialstation O.-Schlemmer-Str. 1 99085 thueringen- 0361/654770 Erfurt [email protected] Erfurt Erfurt Deutschordens-Seniorenhaus gGmbH Sozialstation Vilniuser Str. 14 99089 [email protected] 0361-7720 Erfurt Erfurt Caritas Trägergesellschaft "St. Elisabeth" gGmbH Herderstraße 5 99096 st.elisabeth-erfurt@caritas- 0361/34460 Altenpflegezentrum cte.de Erfurt Erfurt Altenhilfe Sophienhaus gGmbH Martin-Luther- Blosenburgstr. 19 99096 [email protected] 0361/60068153 Haus Erfurt Erfurt Christophoruswerk Erfurt gGmbH - Ambulanter Allerheiligenstr. 8 99084 betreuungsdienst@christophor 0361/21001-550 Betreuungsdienst uswerk.de Erfurt Erfurt MIA, (Miteinander-Inklusiv-Anders), offene Brühler Str. -

The Changing Distribution of Federal Taxes: 1975-1990

The Changing Distribution of Federal Taxes: 1975-1990 CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE U.& CONGRESS WASHINGTON, OC. 20515 ERRATA The Changing Distribution of Federal Taxes: 1975 -1990 October 1987 The attached five pages represent corrections to details in the ref- erenced published CBO report. Readers may wish to detach the sheets and insert them at the appropriate places in the bound report. at page 42 Figure 5. Effective Federal Tax Rates by Population Decile (All taxes combined) Corporate Taxes Allocated Corporate Taxes Allocated to Capital Income to Labor Income 40 1977 Tax Law 1984 Tax Law 1988 Tax Law •? 30 1 !- i £ 10 i I 1234567 8 g 10 * - 123456789 10* Population Daciles H- *— Population Diciles *- SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office tax simulation models. NOTE: Families are ranked by the size of family income. Because family income includes the family's share of the corporate income tax, the ordering of families depends on the allocation of corporate taxes The lowest decile excludes families with zero or negative incomes. The effective tax rate is the ratio of taxes to family income in each income class. CHAPTER VI THE EFFECT OF TAX LAW CHANGES 59 TABLE 11. EFFECTIVE FEDERAL TAX RATES, BY POPULATION DECILE, WITH CONSTANT 1988 INCOMES: CORPORATE INCOME TAX ALLOCATED TO CAPITAL INCOME Individual Social Corporate Income Insurance Income Excise All Decile a/ Tax Taxes Tax Taxes Taxes Income-Indexed 1977 Tax Law First b/ -0.6 3.9 1.1 3.8 8.2 Second -0.7 4.6 1.1 3.6 8.7 Third 1.5 6.8 1.3 2.2 11.8 Fourth 3.9 7.4 1.6 2.1 14.9 Fifth 5.8 7.7 -

Historical Aspects of Thuringia

Historical aspects of Thuringia Julia Reutelhuber Cover and layout: Diego Sebastián Crescentino Translation: Caroline Morgan Adams This publication does not represent the opinion of the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung. The author is responsible for its contents. Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Thüringen Regierungsstraße 73, 99084 Erfurt www.lzt-thueringen.de 2017 Julia Reutelhuber Historical aspects of Thuringia Content 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia 2. The Protestant Reformation 3. Absolutism and small states 4. Amid the restauration and the revolution 5. Thuringia in the Weimar Republic 6. Thuringia as a protection and defense district 7. Concentration camps, weaponry and forced labor 8. The division of Germany 9. The Peaceful Revolution of 1989 10. The reconstitution of Thuringia 11. Classic Weimar 12. The Bauhaus of Weimar (1919-1925) LZT Werra bridge, near Creuzburg. Built in 1223, it is the oldest natural stone bridge in Thuringia. 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia The Ludovingian dynasty reached its peak in 1040. The Wartburg Castle (built in 1067) was the symbol of the Ludovingian power. In 1131 Luis I. received the title of Landgrave (Earl). With this new political landgraviate groundwork, Thuringia became one of the most influential principalities. It was directly subordinated to the King and therefore had an analogous power to the traditional ducats of Bavaria, Saxony and Swabia. Moreover, the sons of the Landgraves were married to the aristocratic houses of the European elite (in 1221 the marriage between Luis I and Isabel of Hungary was consummated). Landgrave Hermann I. was a beloved patron of art. Under his government (1200-1217) the court of Thuringia was transformed into one of the most important centers for cultural life in Europe. -

Can My Church Benefit from a CARES Act Forgivable Loan?

I hope this finds you well and living confidently into the times. Congress passed and the President signed the CARES Act this past Friday, March 27, 2020. I write to share specific information from the CARES Act that answers some of the questions that I have heard being asked. Can my church benefit from a CARES Act forgivable loan? This question is on the minds of most pastors and church leaders since the passage of the $2 trillion relief package. As I continue to participate in some and receive information from other webcasts and conference calls across the connection, there are some things you can begin to do to prepare to apply for the loan program. While I do not encourage you to borrow funds for normal operating expenses, it appears that this loan has the potential to become a grant that you would not need to repay. Attorneys and accountants are studying the bill and awaiting guidelines from the Small Business Administration (SBA) and the U.S. Treasury on how the CARES Act will be administered. However, it appears that churches and non-profits may be able to borrow money that could be completely forgiven if they maintain their previous 12-month staffing levels through June of 2020. Key Provisions: • Paycheck Protection Program (“PPP”) - Eligible churches and non-profits will be able to borrow up to 2.5 times their average monthly payroll and benefits up to $100,000. While this appears to cap the amount to approximately $40,000 of monthly current costs, it is not yet known if that is for all employees in the salary-paying entity or per person. -

Curacao Highlights 2020

International Tax Curaçao Highlights 2020 Updated January 2020 Recent developments: For the latest tax developments relating to Curaçao, see Deloitte tax@hand. Investment basics: Currency – Netherlands Antilles Guilder (ANG) Foreign exchange control – A 1% license fee will be calculated as a percentage of the gross outflow of money on transfers from residents to nonresidents, and on foreign currency cash transactions. Holding companies may obtain an exemption from the fee. Accounting principles/financial statements – IAS/IFRS applies. Financial statements must be prepared annually. Principal business entities – These are the public and private company (NV and BV), general partnership, (private) foundation, Curaçao trust, limited partnership, and branch of a foreign corporation. Corporate taxation: Rates Corporate income tax rate 22%/3%/0% Branch tax rate 22%/3%/0% Capital gains tax rate 22%/3%/0% Residence – A corporation is resident if it is incorporated under the laws of Curaçao or managed and controlled in Curaçao. Basis – In principle, residents are taxed on worldwide income. Exemptions may apply for profits derived by permanent establishments located abroad. In addition, as from 1 July 2018, foreign-source income is excluded from the profit tax base (although there is an exception for certain services, including insurance and reinsurance activities; trust activities; the services of notaries, lawyers, public accountants and tax consultants; related services; income derived from the exploitation of intellectual property (IP); and shipping activities). Page 1 of 7 Curaçao Highlights 2020 Nonresidents are taxed only on Curaçao-source income. Foreign-source income derived by residents that is not excluded from the profit tax base is subject to corporation tax in the same way as Curaçao-source income. -

Die Leiden Des Steuerlichen Wertes

Die Leiden des steuerlichen Wertes Introduction to German Tax Translation Introduction • Basis for taxation in Germany • Major legislative acts • Overview to major tax types • Recent changes to tax law • Resources Basis of Taxation • Grundgesetz (Basic Law) • Abgabenordung, “AO” (General Tax Code) • Finanzgerichtsordnung (Tax Court Procedural Code) Finanzverwaltungsgesetz (Financial/Fiscal Administration Act) Bewertungsgesetz (Valuation Act) • Establishes uniform rules on tax valuation • Applicable to all federal taxes and levies • Defines several common terms, e.g. – gemeiner Wert – Teilwert – Steuerbilanzwert – Einheitswert Major Tax Types • Direct versus indirect • Purpose – Revenue – Repricing (“social” taxes to affect demand) – Redistribution • Taxing (receiving) authority Major Legislation • Einkommensteuergesetz (Personal Income Tax Act) • Körperschaftsteuergesetz (Corporate Income Tax Act) • Umsatzsteuergesetz (Value Added Tax (VAT) Act • Gewerbesteuergesetz (Municipal Trade Tax Act) • Jahressteuergesetz (Annual Tax Act) • Erbschaftsteuergesetz (Inheritance Tax Act) • Grunderwerbsteuergesetz (Real Property Acquisition Tax Act) • Grundsteuergesetz (Real Property Tax Act) • Umwandlungssteuergesetz (Reorganization Tax Act) Tax Revenues in Germany Steuerart Tax Type 2007 revenues Percentage in € bn. 2007 Steueraufkommen Tax revenue 493.818 100.00% insgesamt in Deutschland Total in Germany Gemeinschaftliche Steuern Joint taxes 381.309 77.22% Payroll withholding Lohnsteuer und andere and other personal Einkommensteuern income taxes Direct