Financial Secrecy, Banks and the Big 4 Firms of Accountants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REPLACING CORPORATE TAX REVENUES with a MARK to MARKET TAX on SHAREHOLDER INCOME Eric Toder and Alan D

REPLACING CORPORATE TAX REVENUES WITH A MARK TO MARKET TAX ON SHAREHOLDER INCOME Eric Toder and Alan D. Viard October 2016 ABSTRACT We propose reducing the corporate tax rate to 15 percent and replacing the foregone revenue with a tax at ordinary income rates on the accrued, or mark-to-market income of American shareholders of publicly traded corporations, accompanied by an imputation credit for U.S. corporate income taxes paid. The proposal would dramatically reduce the tax significance of the source of corporate profits and the residence of corporations, both of which can be easily manipulated. Lowering the corporate tax rate to 15 percent would encouraging a capital inflow to the United States and reduce incentives to shift reported profits overseas and engage in inversion transactions while continuing to impose tax on foreigners who earn economic rents from investing in the United States. The proposal includes provisions for averaging of mark-to- market income, transition relief for firms that move from closely held to publicly traded status, and other measures to address the challenges of mark-to-market taxation. We estimate that the proposal would be approximately revenue-neutral and would make the distribution of the tax burden slightly more progressive. A revised version of the article was been published in the September 2016 issue of the National Tax Journal, Volume 69 (3), 701-731. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Tax Policy Center or its funders. I. INTRODUCTION This paper presents a proposal for reform of the taxation of corporate income. -

Double Taxation of Corporate Income in the United States and the OECD

Double Taxation of Corporate Income in the United States and the OECD FISCAL Taylor LaJoie Elke Asen FACT Policy Analyst Policy Analyst No. 740 Jan. 2021 Key Findings • The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act lowered the top integrated tax rate on corporate income distributed as dividends from 56.33 percent in 2017 to 47.47 percent in 2020; the OECD average is 41.6 percent. • Joe Biden’s proposal to increase the corporate income tax rate and to tax long-term capital gains and qualified dividends at ordinary income rates would increase the top integrated tax rate on distributed dividends to 62.73 percent, highest in the OECD. • Income earned in the U.S. through a pass-through business is taxed at an average top combined statutory rate of 45.9 percent. • On average, OECD countries tax corporate income distributed as dividends at 41.6 percent and capital gains derived from corporate income1 at 37.9 percent. • Double taxation of corporate income can lead to such economic distortions as reduced savings and investment, a bias towards certain business forms, and debt financing over equity financing. • Several OECD countries have integrated corporate and individual tax codes to eliminate or reduce the negative effects of double taxation on corporate The Tax Foundation is the nation’s income. leading independent tax policy research organization. Since 1937, our research, analysis, and experts have informed smarter tax policy at the federal, state, and global levels. We are a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. ©2021 Tax Foundation Distributed under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC 4.0 Editor, Rachel Shuster Designer, Dan Carvajal Tax Foundation 1325 G Street, NW, Suite 950 Washington, DC 20005 202.464.6200 1 In some countries, the capital gains tax rate varies by type of asset sold. -

Creating Market Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries

Creating Market Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries Creating Incentives for Greener Products Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries 2014 About the OECD The OECD is a unique forum where governments work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments and concerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the challenges of an ageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where governments can compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice and work to co-ordinate domestic and international policies. The OECD member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The European Union takes part in the work of the OECD. Since the 1990s, the OECD Task Force for the Implementation of the Environmental Action Programme (the EAP Task Force) has been supporting countries of Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia to reconcile their environment and economic goals. About the EaP GREEN programme The “Greening Economies in the European Union’s Eastern Neighbourhood” (EaP GREEN) programme aims to support the six Eastern Partnership countries to move towards green economy by decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation and resource depletion. The six EaP countries are: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Republic of Moldova and Ukraine. -

Tax Policy Update 16 27 April

Policy update Tax Policy Update 16 27 April HIGHLIGHTS • European Parliament: Plenary discusses state of public CBCR negotiations 18 April • Council: member states freeze CCTB negotiations in order to assess its impact on tax bases 20 April • European Commission: new rules for whistleblower protection proposed, covers tax avoidance too 23 April • European Parliament: ECON Committee holds public hearing on definitive VAT system 24 April • European Commission: new Company Law Package with tax dimension published 25 April European Commission Commission kicks off Fair Taxation Roadshow 19 April The European Commission has launched a series of seminars on fair taxation, with a first event held in Riga on 19 April. These seminars bring together civil society, business representatives, policy makers, academics and interested citizens to discuss and exchange views on tax avoidance and tax evasion. Further events are planned throughout 2018 in Austria (17 May), France (8 June), Italy (19 September) and Ireland (9 October). The Commission hopes that the roadshow seminars will further encourage active engagement on tax fairness principles at EU, national and local levels. In particular, a main aim seems to be to spread the tax debate currently ongoing at the EU-level into member states as well. Commission launches VAT MOSS portal 19 April The European Commission has launched a Mini-One Stop Shop (MOSS) portal for VAT purposes. The new MOSS portal provides comprehensive and easily accessible information on VAT rates for telecom, broadcasting and e- services, and explains how the MOSS can be used to declare and pay VAT on such services. 1 Commission proposes EU rules for whistleblower protection, covers tax avoidance as well 23 April The European Commission has published a new Directive for the protection of whistleblowers. -

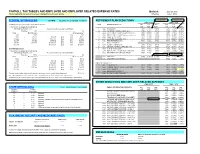

PAYROLL TAX TABLES and EMPLOYEE and EMPLOYER RELATED EXPENSE RATES Updated: June 27, 2012 *Items Highlighted in Yellow Have Been Changed Since the Last Update

PAYROLL TAX TABLES AND EMPLOYEE AND EMPLOYER RELATED EXPENSE RATES Updated: June 27, 2012 *items highlighted in yellow have been changed since the last update. Effective: July 1, 2012 FEDERAL WITHHOLDING 26 PAYS FEDERAL TAX ID NUMBER 86-6004791 RETIREMENT PLAN DEDUCTIONS 10.5% AT 50/50 10.5% AT 50/50 EMPLOYEE EMPLOYER (a) SINGLE person (including head of household) - CODE RETIREMENT PLAN DED OLD NEW DED OLD NEW If the amount of wages (after subtracting CODE RATE RATE CODE RATE RATE withholding allowances) is: The amount of income tax to withhold is: 1 ASRS PLAN-ASRS 7903 11.13% 10.90% 7904 9.87% 10.90% Not Over $83 ............................................................................................. $0 2 CORP JUVENILE CORRECTIONS (501) 7905 8.41% 8.41% 7906 9.92% 12.30% Over But not over - of excess over - 3 EORP ELECTED OFFICIALS & JUDGES (415) 7907 10.00% 11.50% 7908 17.96% 20.87% $83 - $417 10% $83 4 PSRS PUBLIC SAFETY (007) (ER pays 5% EE share) 7909 3.65% 4.55% 7910 38.30% 48.71% $417 - $1,442 $33.40 plus 15% $417 5 PSRS GAME & FISH (035) 7911 8.65% 9.55% 7912 43.35% 50.54% $1,442 - $3,377 $187.15 plus 25% $1,442 6 PSRS AG INVESTIGATORS (151) 7913 8.65% 9.55% 7914 90.08% 136.04% $3,377 - $6,954 $670.90 plus 28% $3,377 7 PSRS FIRE FIGHTERS (119) 7915 8.65% 9.55% 7916 17.76% 20.54% $6,954 - $15,019 $1,672.46 plus 33% $6,954 9 N/A NO RETIREMENT $15,019 ………………………………………………………$4,333.91 plus 35% $15,019 0 CORP CORRECTIONS (500) 7901 8.41% 8.41% 7902 9.15% 11.14% B PSRS LIQUOR CONTROL OFFICER (164) 7923 8.65% 9.55% 7924 38.77% 46.99% (b) MARRIED person F PSRS STATE PARKS (204) 7931 8.65% 9.55% 7932 18.50% 25.16% If the amount of wages (after subtracting G CORP PUBLIC SAFETY DISPATCHERS (563) 7933 7.96% 7.96% 7934 7.50% 7.90% withholding allowances) is: The amount of income tax to withhold is: H PSRS DEFERRED RET OPTION (DROP) 7957 8.65% 9.55% 0.24% AT 50/50 Not Over $312 ............................................................................................ -

NOTICE: This Is an Unofficial Transcript of the Public Company Accounting

NOTICE: This is an unofficial transcript of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board’s June 28, 2012 Public Meeting on Auditor Independence and Audit Firm Rotation. The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board does not certify the accuracy of this unofficial transcript, which may contain typographical or other errors or omissions. An archive of the webcast of the meeting can be found on the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board’s website at: http://pcaobus.org/News/Webcasts/Pages/06282012_PublicMeeting.aspx 1 PUBLIC COMPANY ACCOUNTING OVERSIGHT BOARD + + + + + AUDITOR INDEPENDENCE AND AUDIT FIRM ROTATION PCAOB RULEMAKING DOCKET MATTER NO. 37 + + + + + PUBLIC MEETING + + + + + THURSDAY JUNE 28, 2012 + + + + + The Public Meeting convened at the Hilton San Francisco Financial District, 750 Kearny Street, San Francisco, California, at 8:00 a.m., Jim Doty, PCAOB Chairman, presiding. THE BOARD JAMES R. DOTY, Chairman LEWIS H. FERGUSON, Board Member JEANETTE M. FRANZEL, Board Member JAY D. HANSON, Board Member STEVEN B. HARRIS, Board Member PCAOB STAFF MARTIN F. BAUMANN, PCAOB, Chief Auditor and Director of Professional Standards MICHAEL GURBUTT, Associate Chief Auditor J. GORDON SEYMOUR, General Counsel JACOB LESSER, Associate General Counsel OBSERVERS BRIAN CROTEAU, Securities and Exchange Commission NEAL R. GROSS COURT REPORTERS AND TRANSCRIBERS 1323 RHODE ISLAND AVE., N.W. (202) 234-4433 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005-3701 www.nealrgross.com 2 PANELISTS JULIE ALLECTA, Trustee and Chairman of the Audit Committee, Forward Funds JANICE HESTER AMEY, Portfolio Manager, Corporate Governance, California State Teachers' Retirement System (CalSTRS) ANDREW D. BAILEY, JR., Professor Emeritus, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; former Deputy Chief Accountant, US Securities and Exchange Commission WILLIAM H. -

Guide to Fiscal Information

Guide to Fiscal Information Key Economies in Africa 2014/15 Preface This booklet contains a summary of tax and investment information pertaining to key countries in Africa. This year’s edition of the booklet has been expanded to include an additional five countries over- and-above the thirty-five countries featured in last year’s edition. The forty countries featured this year comprise: Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Congo (Brazzaville), Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Egypt, Ethiopia, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea Conakry, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Lesotho, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, South Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Details of each country’s income tax, VAT (or sales tax), and other significant taxes are set out in the publication. In addition, investment incentives available, exchange control regimes applicable (if any) and certain other basic economic statistics are detailed. The contact details for each country are provided on the cover page of each country chapter/ section and also summarised on page 4, Tax Leaders in Africa. An introduction to the Africa Tax Desk (including relevant contact details) is provided on page 3, Africa Tax Desk. This booklet has been prepared by the Tax Division of Deloitte. Its production was made possible by the efforts of: • Moray Wilson, Adrienne Snyman and Susan Heiman – editorial management, content and design. • Bruno Messerschmitt, Musa Manyathi and Sarah Naiyeju – Deloitte Africa Tax Desk. • Deloitte colleagues (and Independent Correspondent Firm staff where necessary) in various cities/offices in Africa and elsewhere. -

Dividends and Capital Gains Information Page 1 of 2

Dividends and Capital Gains Information Page 1 of 2 Some of the dividends you receive and all net long term capital gains you recognize may qualify for a federal income tax rate As noted above, for purposes of determining qualified dividend lower than your federal ordinary marginal rate. income, the concept of ex-dividend date is crucial. The ex- dividend date of a fund is the first date on which a person Qualified Dividends buying a fund share will not receive any dividends previously declared by the fund. A list of fund ex-dividend dates for each Qualified dividends received by you may qualify for a 20%, 15% State Farm Mutual Funds® dividend paid with respect to 2020, or 0% tax rate depending on your adjusted gross income (or and the corresponding percentage of each dividend that may AGI) and filing status. For single filing status, the qualified qualify as qualified dividend income, is provided below for your dividend tax rate is 0% if AGI is $40,000 or less, 15% if AGI is reference. more than $40,000 and equal to or less than $441,450, and 20% if AGI is more than $441,450. For married filing jointly Example: status, the qualified dividend tax rate is 0% if AGI is $80,000 or You bought 10,000 shares of ABC Mutual Fund common stock less, 15% if AGI is more than $80,000 and equal to or less than on June 8, 2020. ABC Mutual Fund paid a dividend of 10 cents $496,600, and 20% if AGI is more than $496,600. -

FINANCE Offshore Finance.Pdf

This page intentionally left blank OFFSHORE FINANCE It is estimated that up to 60 per cent of the world’s money may be located oVshore, where half of all financial transactions are said to take place. Meanwhile, there is a perception that secrecy about oVshore is encouraged to obfuscate tax evasion and money laundering. Depending upon the criteria used to identify them, there are between forty and eighty oVshore finance centres spread around the world. The tax rules that apply in these jurisdictions are determined by the jurisdictions themselves and often are more benign than comparative rules that apply in the larger financial centres globally. This gives rise to potential for the development of tax mitigation strategies. McCann provides a detailed analysis of the global oVshore environment, outlining the extent of the information available and how that information might be used in assessing the quality of individual jurisdictions, as well as examining whether some of the perceptions about ‘OVshore’ are valid. He analyses the ongoing work of what have become known as the ‘standard setters’ – including the Financial Stability Forum, the Financial Action Task Force, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. The book also oVers some suggestions as to what the future might hold for oVshore finance. HILTON Mc CANN was the Acting Chief Executive of the Financial Services Commission, Mauritius. He has held senior positions in the respective regulatory authorities in the Isle of Man, Malta and Mauritius. Having trained as a banker, he began his regulatory career supervising banks in the Isle of Man. -

Tax Us If You Can 2012 FINAL.Pdf

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Murphy, R. and Christensen, J.F. (2012). Tax us if you can. Chesham, UK: Tax Justice Network. This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16543/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] tax us nd if you can 2Edition INTRODUCTION TO THE TAX JUSTICE NETWORK The Tax Justice Network (TJN) brings together charities, non-governmental organisations, trade unions, social movements, churches and individuals with common interest in working for international tax co-operation and against tax avoidance, tax evasion and tax competition. What we share is our commitment to reducing poverty and inequality and enhancing the well being of the least well off around the world. In an era of globalisation, TJN is committed to a socially just, democratic and progressive system of taxation. -

Tax Heavens: Methods and Tactics for Corporate Profit Shifting

Tax Heavens: Methods and Tactics for Corporate Profit Shifting By Mark Holtzblatt, Eva K. Jermakowicz and Barry J. Epstein MARK HOLTZBLATT, Ph.D., CPA, is an Associate Professor of Accounting at Cleveland State University in the Monte Ahuja College of Business, teaching In- ternational Accounting and Taxation at the graduate and undergraduate levels. axes paid to governments are among the most significant costs incurred by businesses and individuals. Tax planning evaluates various tax strategies in Torder to determine how to conduct business (and personal transactions) in ways that will reduce or eliminate taxes paid to various governments, with the objective, in the case of multinational corporations, of minimizing the aggregate of taxes paid worldwide. Well-managed entities appropriately attempt to minimize the taxes they pay while making sure they are in full compliance with applicable tax laws. This process—the legitimate lessening of income tax expense—is often EVA K. JERMAKOWICZ, Ph.D., CPA, is a referred to as tax avoidance, thus distinguishing it from tax evasion, which is illegal. Professor of Accounting and Chair of the Although to some listeners’ ears the term tax avoidance may sound pejorative, Accounting Department at Tennessee the practice is fully consistent with the valid, even paramount, goal of financial State University. management, which is to maximize returns to businesses’ ownership interests. Indeed, to do otherwise would represent nonfeasance in office by corporate managers and board members. Multinational corporations make several important decisions in which taxation is a very important factor, such as where to locate a foreign operation, what legal form the operations should assume and how the operations are to be financed. -

EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01 FRIDAY 13Th SEPTEMBER the BIG FOUR

EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01 FRIDAY 13th SEPTEMBER THE BIG FOUR PROFESSIONAL SERVICES ORGANISATIONS LATEST TO JOIN FORCES ON BUSINESS DISABILITY INCLUSION • The Big Four professional service organisations, Deloitte UK, EY, KPMG UK and PwC UK have signed up to disability inclusion campaign The Valuable 500 • The campaign is seeking 500 global business leaders and brands to commit to putting disability on their board agendas in 2019 • This marks the first ever collaboration on disability inclusion in business between all four leading accountancy organisations LONDON, 13th SEPTEMBER: Deloitte UK, KPMG UK and PwC UK have today announced that they have signed up to The Valuable 500 – the global initiative striving to place disability inclusion on the business agenda. EY has already pledged to The Valuable 500 at a global level. This collaborative move from the leading professional services organisations places the sector at the forefront of creating better inclusivity in business. This move follows the large number of banks that recently committed to The Valuable 500 including Barclays, HSBC, Bank of England, RBS and Lloyds Banking Group, signifying a huge step forward for the financial sector as a whole. The Valuable 500, launched at the World Economic Forum’s Annual Summit in Davos earlier this year, is seeking 500 global business leaders to place disability on their board agendas, and will hold each accountable for disability inclusion in their businesses by ensuring it is discussed at leadership level and action is taken. To date businesses employing well over two million employees globally have signed up to put disability inclusion on their board agendas.