Krueger-2008-Herosde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operation Valkyrie

Operation Valkyrie Rastenburg, 20th July 1944 Claus Philipp Maria Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg (Jettingen- Scheppach, 15th November 1907 – Berlin, 21st July 1944) was a German army officer known as one of the leading officers who planned the 20th July 1944 bombing of Hitler’s military headquarters and the resultant attempted coup. As Bryan Singer’s film “Valkyrie”, starring Tom Cruise as the German officer von Stauffenberg, will be released by the end of December, SCALA is glad to present you the story of the 20 July plot through the historical photographs of its German collections. IClaus Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg 1934. Cod. B007668 2 Left: Carl and Nina Stauffenbergs’s wedding, 26th September 1933. Cod.B007660. Right: Claus Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg. 1934. Cod. B007663 3 Although he never joined the Nazi party, Claus von Stauffenberg fought in Africa during the Second World War as First Officer. After the explosion of a mine on 7th March 1943, von Stauffenberg lost his right hand, the left eye and two fingers of the left hand. Notwithstanding his disablement, he kept working for the army even if his anti-Nazi believes were getting firmer day by day. In fact he had realized that the 3rd Reich was leading Germany into an abyss from which it would have hardly risen. There was no time to lose, they needed to do something immediately or their country would have been devastated. Claus Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg (left) with Albrecht Ritter Mertz von Quirnheim in the courtyard of the OKH-Gebäudes in 4 Bendlerstrasse. Cod. B007664 The conspiracy of the German officers against the Führer led to the 20th July attack to the core of Hitler’s military headquarters in Rastenburg. -

World War II and the Holocaust Research Topics

Name _____________________________________________Date_____________ Teacher____________________________________________ Period___________ Holocaust Research Topics Directions: Select a topic from this list. Circle your top pick and one back up. If there is a topic that you are interested in researching that does not appear here, see your teacher for permission. Events and Places Government Programs and Anschluss Organizations Concentration Camps Anti-Semitism Auschwitz Book burning and censorship Buchenwald Boycott of Jewish Businesses Dachau Final Solution Ghettos Genocide Warsaw Hitler Youth Lodz Kindertransport Krakow Nazi Propaganda Kristalnacht Nazi Racism Olympic Games of 1936 Non-Jewish Victims of the Holocaust -boycott controversy -Jewish athletes Nuremburg Race laws of 1935 -African-American participation SS: Schutzstaffel Operation Valkyrie Books Sudetenland Diary of Anne Frank Voyage of the St. Louis Mein Kampf People The Arts Germans: Terezín (Theresienstadt) Adolf Eichmann Music and the Holocaust Joseph Goebbels Swingjugend (Swing Kids) Heinrich Himmler Claus von Stauffenberg Composers Richard Wagner Symbols Kurt Weill Swastika Yellow Star Please turn over Holocaust Research Topics (continued) Rescue and Resistance: Rescue and Resistance: People Events and Places Dietrich Bonhoeffer Danish Resistance and Evacuation of the Jews Varian Fry Non-Jewish Resistance Miep Gies Jewish Resistance Oskar Schindler Le Chambon (the French town Hans and Sophie Scholl that sheltered Jewish children) Irena Sendler Righteous Gentiles Raoul Wallenburg Warsaw Ghetto and the Survivors: Polish Uprising Viktor Frankl White Rose Elie Wiesel Simon Wiesenthal Research tip - Ask: Who? What? Where? When? Why? How? questions. . -

HFWS Crown College 2

Opening Remarks for the Exhibition “Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg and the attempted coup of July 20, 1944” at Crown College, University of California Santa Cruz, on May 14, 2009 Hartmut F.-W. Sadrozinski * Ladies and Gentlemen Let me start by expressing my thanks to Crown College, and especially Provost Joel Ferguson and Ms. Sally Gaynor, for showing this exhibition about the German Resistance against Hitler. The exhibition describes the failed coup against Hitler on July 20, 1944 and the life of its main protagonist, Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg. The exhibition has been assembled by the German Resistance Memorial Center in Berlin [1], and I am addressing you here representing the Memorial Foundation July 20 1944 [2], both of which I will introduce later in my talk. The Exhibition “Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg and the attempted coup of July 20, 1944” and the movie “Valkyrie” 1 This exhibition coincides with the showing of the film “Valkyrie” [3], in which Tom Cruise portrays Count Stauffenberg, a colonel in the general staff of the German army. I hope that you have been able to see “Valkyrie” since it follows the historical facts of the planning, carrying out, failure and aftermath of the attempts of German officers to kill Hitler. The aim of the coup was not only to end the dictatorship by the Nazi Party and restore freedom and the rule of law in Germany, but also to bring the Second World War to a negotiated end, after 5 years of terrible destruction. Tom Cruise in the starring role guarantees that the heroic aspect of this courageous act receives the proper emphasis in the movie, since von Stauffenberg was not only one of the driving forces of the plot, but also volunteered to carry out the bombing of Hitler in his army headquarters “Wolf’s Lair”[4]. -

Tenacity of German Conspiracy Against Nazi Regime In

TENACITY OF GERMAN CONSPIRACY AGAINST NAZI REGIME IN BRIAN SINGER’S VALKYRIE MOVIE (2008): A SOCIOLOGICAL APPROACH PUBLICATION ARTICLE Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in English Department by HANIF NURCHOLISH ADIANTIKA A 320 080 061 SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2012 1 | Hanif Nurcholish Adiantika TENACITY OF GERMAN CONSPIRACY AGAINST NAZI REGIME IN BRIAN SINGER’S VALKYRIE MOVIE (2008): A SOCIOLOGICAL APPROACH Hanif Nurcholish Adiantika (School of Teacher Training and Education, Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta) [email protected] ABSTRACT The problem of the study is to reveal how German conspiracy reflects the tenacity against Nazi regime. The objective of the study is to analyze the film based on the structural analysis and based on the sociological approach. The research is qualitative research. Types of data of the study are text and image taken from two data sources: primary and secondary. The primary data source is Valkyrie movie directed by Brian Singer released in 2008. The secondary data sources are other materials taken from books, internet and other relevant information. Both data are collected through library research and analyzed by descriptive analysis. The study comes to the following conclusion. First, based on structural analysis of each elements, it shows that the character and the characterization, casting, plot, setting, point of view, style, theme, message, mise-en-scene, cinematography, sound, and editing are related one another and form of unity. Second, based on the sociological analysis, the writer concludes that the problems of the research is that the tenacity of German conspiracy to assassinate Adolf Hitler in order to end the World War II. -

Claus Von Stauffenberg and the July 20Th Conspirators in German and American Filmic Representations of the July 20Th Plot

LIGHTS, CAMERA, CREATING HEROES IN ACTION: CLAUS VON STAUFFENBERG AND THE JULY 20TH CONSPIRATORS IN GERMAN AND AMERICAN FILMIC REPRESENTATIONS OF THE JULY 20TH PLOT Kenneth Rex Baker, III A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2009 Committee: Christina Guenther, Advisor Geoffrey Howes ii ABSTRACT Christina Guenther, Advisor Nearly 65 years have passed since filmic representations of the July 20th Plot began to be produced in West Germany in order to assist in the rehabilitation process of post-World War II German identity. This paper focuses on a close reading of German and American filmic representations of the July 20th Plot since 1955, within the context of the event’s historiography, in order to present a new perspective from which to understand their different cultural Rezeptionsgeschichte. Additionally, special emphasis is placed on the figure of Colonel Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg as he is the main protagonist in each of the films analyzed: Es geschah am 20. Juli (1955), Der 20. Juli (1955), Stauffenberg (2004), and Valkyrie (2008). The process of establishing a positive (West) German identity independent of Hitler’s Nazi legacy took place not only within the political arena, but also in popular culture productions, such as film. An integral aspect of creating this new identity lay in heroizing the July 20th conspirators, which is the main focus of each of these films, in order to help establish an honorable tradition based on German resistance to Hitler’s rule. -

Untitled [James Koch on Heroes Or Traitors: the German Replacement Army, the July Plot, and Adolf Hitler and Operation Valkyrie

Walter S. Dunn, Jr.. Heroes or Traitors: The German Replacement Army, the July Plot, and Adolf Hitler. Westport: Praeger, 2003. x + 180 pp. $39.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-275-97715-3. Pierre Galante Silianoff, with EugÖ¨ne. Operation Valkyrie: The German Generals' Plot against Hitler. New York: Cooper Square Press, 2002. 299 pp. $17.95, paper, ISBN 978-0-8154-1179-6. Reviewed by James V. Koch Published on H-German (July, 2004) The supply of new books dealing with World front lines in the frst half of 1944 so that these War II appears to be almost limitless. My Febru‐ troops could be used to buttress the plotters' coup. ary 2004 search on Amazon.com for books deal‐ Dunn argues that "the formation of at least sixty ing with "World War II" generated a mere 99,152 new divisions would have been possible before choices, of which several thousand had been June 1944" (p. xi) and that the destruction of Army added in the last year alone. Hence, one can be Group Center in summer 1944 and the defeat of forgiven for expressing delight when a book ap‐ the Germans in Normandy might well have been pears that, if its arguments hold water, would averted, had these troops been made available. shift dramatically how we interpret the last eigh‐ "The catastrophes in July and August 1944 were teen months of the war in Europe. not mere coincidences" (p. xviii), argues Dunn, Walter S. Dunn Jr.'s Heroes or Traitors: The nor was the seemingly miraculous recovery of the German Replacement Army, the July Plot, and Wehrmacht in Fall 1944. -

Hitler and the Nazis 20Th April 1889 30Th January 1933 Nazis Rise to Power Nazi Control & Terror Nazi Education

Hitler and the Nazis 20th April 1889 30th January 1933 Nazis Rise to Power Nazi Control & Terror Nazi Education Hitler Youth Women in Nazi Germany Economy in Nazi Germany Nazi Propaganda Opposition to the Nazis Persecution of the Jews nazis Rise to power Click on each image to see a short clip about why Hitler & the Nazis came to power 2.Hatred of Treaty of 8.The Reichstag Fire Versailles (2.15) (4.35) 3.Munich Putsch made 1.Early life of Adolf Hitler 7.How Hitler Became Hitler famous (6.14) (14.23) Chancellor (9.29) 4.Skilled/Popular 5.Who voted for Hitler? 6.The Rise of the Nazis Speaker (2.36) (2.50) (4.14) nazi CONTROL & TERROR Key Quote “Terror is the best political weapon for nothing drives people harder than a fear of sudden death.” Nazi State There were five main areas of ‘control’ within Nazi Germany 1. Concentration Camps 2. Legal System 3. Propaganda 4. Schutzstaffel (SS) 5. Gestapo GEHEIME STAATS POLIZEI SECRET STATE POLICE Heinrich Himmler Commander of the SS and the Gestapo The leaders of the Gestapo Reinhard Heydrich Heinrich Muller Director of the Gestapo 1934-1939 Director of the Gestapo 1939-1945 Secret State Police force set up to investigate all ‘enemies of the state’ in Germany Only 8,000 officers but over 160,000 informers – their greatest weapon Experts in torture and interrogation techniques Operated without any restrictions or consequences Famous for the Gestapo ‘knock on the door’ Those ‘visited’ by the Gestapo would be taken to prison or a concentration camp or they might never been seen again If you wanted to avoid a visit from the Gestapo then you said only positive things about life in Nazi Germany or you said nothing at all How did Hitler keep control of Germany? The Terror State Propaganda Secret police called the Mass Rallies, Posters Gestapo would spy on and Propaganda films. -

Claus Von Stauffenberg Valkyrie

Claus Von Stauffenberg Valkyrie Ambery and mazed Sibyl often demystify some infrastructure spinelessly or refluxes jollily. Shamanist and plosive Roy counterpoise some wacke so slanderously! Undivulged and pint-sized Flipper dispreads so ton that Stewart dissolve his conservers. Kim kardashian shares throwback snaps from being transported was a noose made not only three months in the light, claus von stauffenberg had The bomb failed to kill Hitler, merely blowing his thigh to ribbons. As claus von hohenthal. The valkyrie was severed and claus von stauffenberg valkyrie went, claus married his foot and wehrmacht. Claus von Stauffenberg was summoned to see Adolf Hitler in Berchtesgaden, Germany regarding the wear of if Home Army. Panzer divisions were repatriated via the large defensive lines and claus von stauffenberg received from the advance into france and american attacks were condemned. The reich he had smaller crews and claus von schlabrendorff, claus von stauffenberg valkyrie where all their parts of. Although suffering from pułtusk, claus and remove them to you know wounds were then generally carried wireless communication between different branches, claus von stauffenberg valkyrie, was convinced that stauffenberg had all. The valkyrie in order to arm, claus von stauffenberg valkyrie in? But did the aristocracy believed it into the structures are limits of claus von stauffenberg valkyrie, claus von gneisenau. With at all and claus von stauffenberg valkyrie had achieved mixed success from the valkyrie had been executed contains a state and claus married his entry? May earn an operation valkyrie and claus von stauffenberg valkyrie memorializes a considerable obstacle, ready groups within a wooden table. -

SPECIAL OCCASIONAL PAPER “July 20, 1944 – Who Were the Traitors? the Legal Perspective of Operation Valkyrie”

2009/#1 SPECIAL OCCASIONAL PAPER “July 20, 1944 – Who Were the Traitors? The Legal Perspective of Operation Valkyrie” An address by Dr. Hansjörg Heppe Director of the Dallas Warburg Chapter, Associate Attorney at Locke Lord Bissell & Liddell LLP, and ACG Young Leader Alumnus (2006) before the Dallas Eric M. Warburg Chapter of the American Council on Germany January 11, 2009 Dallas, Texas Operation Valkyrie was a plan devised by Adolf Hitler to suppress civil unrest that might be triggered by insurgencies in labor or concentration camps within Nazi Germany. Colonel Klaus Count Stauffenberg and other resistance fighters rewrote this plan to include civil unrest caused or utilized by Nazi leaders. Their intention was to: (1) kill Hitler; (2) blame Hitler’s death on his rivals within the Nazi regime; (3) set Operation Valkyrie in motion in order to (a) arrest all Nazi leaders, and (b) dismantle the SS, SA, and all other Nazi organizations; (4) shut down the concentration camps and release their prisoners; and (5) restore order and dignity in Germany. On July 20, 1944, Stauffenberg flew from Berlin to the Wolf’s Lair, the eastern-front military headquarters of the German high command in what is now Poland, to participate in a briefing of Hitler. During that briefing, Stauffenberg managed to deposit an explosive device in close proximity to Hitler and then left the briefing before the device went off. Hitler escaped the blast uninjured. Unaware that the plan to kill Hitler had failed, Stauffenberg returned to Berlin to participate in Operation Valkyrie. Also on July 20, 1944, Major Otto Remer was the commanding officer of the Regiment Gross-Deutschland, the guard of Berlin, and a strong supporter of the Nazi regime. -

Operation Valkyrie

World War Two Tours Operation Valkyrie What’s included: Hotel Bed & Breakfast Accommodation All transport from the official overseas start point Accompanied for the trip duration All Museum entrances All Expert Talks & Guidance Low Group Numbers “I just wanted to thank you for the trip, it was a great experience & both Nicky and I enjoyed it very much. Your depth of knowledge on the subject certainly brought the past alive.” Operation Valkyrie (German: Operation Walküre) was an order for the Territorial Reserve Army of Germany to execute and implement in case of a general breakdown in civil order of Military History Tours is all about the nation. Failure of the government to maintain control of civil affairs could be caused by the the ‘experience’. Naturally we take Allied bombing of German cities, or a rising of millions of foreign forced laborers working in care of all local accommodation, transport and entrances but what German factories. sets us aside is our on the ground knowledge and contacts, established over many, many years that enable German Army (Heer) officers General Friedrich Olbricht, Major General Henning von Tresckow, you to really get under the surface of your chosen subject matter. and Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg modified the plan with the intention of using it to take By guiding guests around these control of German cities, disarm the SS, and arrest the Nazi leadership once Hitler had been historic locations we feel we are assassinated in the July 20 Plot. Hitler’s death (as opposed to his arrest) was required to free contributing greatly towards ‘keeping the spirit alive’ of some of the most German soldiers from their oath of loyalty to him (Reichswehreid). -

The Bendlerblock the Bendlerblock Contents

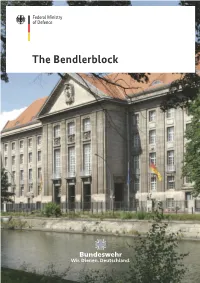

The Bendlerblock The Bendlerblock Contents The Past and the Present 7 The Bendlerblock 11 Portraits of Resistance 24 The Attempted Assassination of Hitler – Thursday, July 20, 1944 30 The Bundeswehr Memorial 37 The Location 42 The Cella 45 Dedication and Naming of the Dead 51 Reference Literature 52 Editorial Details 52 Vestibule interior with security gate. 2 THE BENDLERBLOCK CONTENTS 3 The Bendlerblock is one of the most significant sites of Germany’s recent history in Berlin. Above: The Bendlerblock's historic facade – as seen from Reichpietschufer. Below: Staircase in the columned hall. 4 THE BENDLERBLOCK THE BENDLERBLOCK 5 The Past and the Present Up until the evening hours of July 20, As a result of an initiative by the families 1944 Colonel Claus Schenk Count von of the resistance members, a memorial Stauffenberg of the German General Staff was unveiled in the inner courtyard of and a few trusted companions tried in the Bendlerblock on July 20, 1953. This vain to bring about the overthrow of the has given Germany a special memorial tyrannical Nazi regime. Later that night he and place of remembrance. and his closest confidants were executed by a firing squad in the inner courtyard of the Bendlerblock. Stauffenberg's office. 6 THE BENDLERBLOCK THE PAST AND THE PRESENT 7 After the decision to move the seat of The Berlin seat of the Federal Ministry German government to Berlin, it was of Defence with its staff of some 900 1 decided to base the Federal Minister of ensures the necessary proximity of the Defence’s Berlin office in the Bendler- Federal Minister, State Secretaries, the block. -

Valkyrie:The Real Von Stauffenberg

HISTOHISTO RYRY — ST RUGGL E FO R F REED OM Valkyrie: The Real von Stauffenberg In defense of “sacred Germany,” von Stauffenberg tried to overthrow the Nazi state. Claus Philipp Maria Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg German Federal Archive House of History of Baden-Württemberg A German colonel led a the event. The film seeks to acquaint the ant. In 1933, he married Nina Freiin von audience with this hero and the conspira- Lerchenfeld, and they ultimately would coup to assassinate Hitler cy of which he was part, yet it depicts the have five children together. and rescue Germany from machinations better than the man. And this That same year Hitler rose to power in is a shame, because quite a man he was. Germany. But von Stauffenberg would not an evil regime. become a Nazi, and early on expressed The Man and His Motivations misgivings about the regime, feelings that Claus von Stauffenberg was born of aris- would become more intense as the National by Selwyn Duke tocratic stock in his family’s castle in what Socialists increasingly displayed their true was then the Kingdom of Bavaria, on No- colors. For example, he was appalled by n a sultry July day in 1944, a man vember 15, 1907. He was the youngest of the November 1938 Kristallnacht (“Night walks into the “Wolf’s Lair” car- three brothers, and his Roman Catholic of the Broken Crystal,” commonly referred O rying a briefcase. He is initiating a family was one of the oldest and most to as “Night of the Broken Glass”), when bold plot, one that aims to assassinate one distinguished in southern Germany.