The Cyprus Problem in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Votes and Proceedings

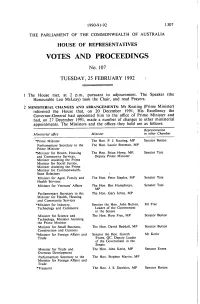

1990-91-92 1307 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 107 TUESDAY, 25 FEBRUARY 1992 1 The House met, at 2 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. The Speaker (the Honourable Leo McLeay) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 MINISTERIAL CHANGES AND ARRANGEMENTS: Mr Keating (Prime Minister) informed the House that, on 20 December 1991, His Excellency the Governor-General had appointed him to the office of Prime Minister and had, on 27 December 1991, made a number of changes to other ministerial appointments. The Ministers and the offices they hold are as follows: Representation Ministerial office Minister in other Chamber *Prime Minister The Hon. P. J. Keating, MP Senator Button Parliamentary Secretary to the The Hon. Laurie Brereton, MP Prime Minister *Minister for Health, Housing The Hon. Brian Howe, MP, Senator Tate and Community Services, Deputy Prime Minister Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Social Justice, Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Commonwealth- State Relations I Minister for Aged, Family and The Hon. Peter Staples, MP Senator Tate Health Services Minister for Veterans' Affairs The Hon. Ben Humphreys, Senator Tate MP Parliamentary Secretary to the The Hon. Gary Johns, MP Minister for Health, Housing and Community Services *Minister for Industry, Senator the Hon. John Button, Mr Free Technology and Commerce Leader of the Government in the Senate Minister for Science and The Hon. Ross Free, MP Senator Button Technology, Minister Assisting the Prime Minister Minister for Small Business, The Hon. David Beddall, MP Senator Button Construction and Customs *Minister for Foreign Affairs and Senator the Hon. -

Trade Mission to New Zealand and Australia

1 106TH CONGRESS "!WMCP: 2d Session COMMITTEE PRINT 106±16 SUBCOMMITTEE ON TRADE OF THE COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES REPORT ON TRADE MISSION TO NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA MARCH 1999 Prepared for the use of Members of the Committee on Ways and Means by members of its staff. This document has not been officially approved by the Committee and may not reflect the views of its Members U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 68±478 CC WASHINGTON : 2001 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 VerDate 20-JUL-2000 11:57 Jan 08, 2001 Jkt 061710 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 K:\HEARINGS\68478.TXT WAYS3 PsN: WAYS3 COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS BILL ARCHER, Texas, Chairman PHILIP M. CRANE, Illinois CHARLES B. RANGEL, New York BILL THOMAS, California FORTNEY PETE STARK, California E. CLAY SHAW, JR., Florida ROBERT T. MATSUI, California NANCY L. JOHNSON, Connecticut WILLIAM J. COYNE, Pennsylvania AMO HOUGHTON, New York SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan WALLY HERGER, California BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland JIM MCCRERY, Louisiana JIM MCDERMOTT, Washington DAVE CAMP, Michigan GERALD D. KLECZKA, Wisconsin JIM RAMSTAD, Minnesota JOHN LEWIS, Georgia JIM NUSSLE, Iowa RICHARD E. NEAL, Massachusetts SAM JOHNSON, Texas MICHAEL R. MCNULTY, New York JENNIFER DUNN, Washington WILLIAM J. JEFFERSON, Louisiana MAC COLLINS, Georgia JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee ROB PORTMAN, Ohio XAVIER BECERRA, California PHILIP S. ENGLISH, Pennsylvania KAREN L. THURMAN, Florida WES WATKINS, Oklahoma LLOYD DOGGETT, Texas J.D. HAYWORTH, Arizona JERRY WELLER, Illinois KENNY HULSHOF, Missouri SCOTT MCINNIS, Colorado RON LEWIS, Kentucky MARK FOLEY, Florida A.L. -

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

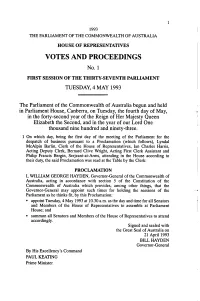

1993 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT TUESDAY, 4 MAY 1993 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Tuesday, the fourth day of May, in the forty-second year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and ninety-three. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (which follows), Lyndal McAlpin Barlin, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Ian Charles Harris, Acting Deputy Clerk, Bernard Clive Wright, Acting First Clerk Assistant and Philip Francis Bergin, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION I, WILLIAM GEORGE HAYDEN, Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, acting in accordance with section 5 of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia which provides, among other things, that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit, by this Proclamation: " appoint Tuesday, 4 May 1993 at 10.30 a.m. as the day and time for all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives to assemble at Parliament House; and * summon all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives to attend accordingly. Signed and sealed with the Great Seal of Australia on 21 April 1993 BILL HAYDEN Governor-General By His Excellency's Command PAUL KEATING Prime Minister No. -

Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic

Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Robert J. Bookmiller Gulf Research Center i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Dubai, United Arab Emirates (_}A' !_g B/9lu( s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ *_D |w@_> TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B uG_GAE#'c`}A' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB9f1s{5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'cAE/ i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBª E#'Gvp*E#'B!v,¢#'E#'1's{5%''tDu{xC)/_9%_(n{wGLi_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uAc8mBmA' , ¡dA'E#'c>EuA'&_{3A'B¢#'c}{3'(E#'c j{w*E#'cGuG{y*E#'c A"'E#'c CEudA%'eC_@c {3EE#'{4¢#_(9_,ud{3' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBB`{wB¡}.0%'9{ymA'E/B`d{wA'¡>ismd{wd{3 *4#/b_dA{w{wdA'¡A_A'?uA' k pA'v@uBuCc,E9)1Eu{zA_(u`*E @1_{xA'!'1"'9u`*1's{5%''tD¡>)/1'==A'uA'f_,E i_m(#ÆA Gulf Research Center 187 Oud Metha Tower, 11th Floor, 303 Sheikh Rashid Road, P. O. Box 80758, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Tel.: +971 4 324 7770 Fax: +971 3 324 7771 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.grc.ae First published 2009 i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Gulf Research Center (_}A' !_g B/9lu( Dubai, United Arab Emirates s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ © Gulf Research Center 2009 *_D All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in |w@_> a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Gulf Research Center. -

Howard's Decade

Lowy Institute Paper 15 howard’s decade AN AUSTRALIAN FOREIGN POLICY REAPPRAISAL Paul Kelly Lowy Institute Paper 15 howard’s decade AN AUSTRALIAN FOREIGN POLICY REAPPRAISAL Paul Kelly First published for Lowy Institute for International Policy 2006 PO Box 102 Double Bay New South Wales 2028 Australia www.longmedia.com.au [email protected] Tel. (+61 2) 9362 8441 Lowy Institute for International Policy © 2006 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part Paul Kelly is Editor-at-Large of The Australian. He was of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (including but not limited to electronic, previously Editor-in-Chief of The Australian. He writes mechanical, photocopying, or recording), without the prior written permission of the on Australian and international issues and is a regular copyright owner. commentator on ABC television. Paul holds a Doctor of Letters from the University of Cover design by Holy Cow! Design & Advertising Melbourne and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Printed and bound in Australia Typeset by Longueville Media in Esprit Book 10/13 Sydney. He has honorary doctorates from the University of New South Wales and from Griffi th University, and is National Library of Australia a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia. Cataloguing-in-Publication data He has been a Shorenstein Fellow at the Kennedy School at Harvard University and a visiting lecturer at the Kelly, Paul, 1947- . Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard. -

No Aircraft Noise Party Inc P.O

Ms Winifred Southcott, President No Aircraft Noise Party Inc P.O. Box 613 Petersham 2049 Email: [email protected] Web site: noaircraftnoise.org.au Airport Regulation inquiry Productivity Commission Locked Bag 2 Collins Street East Victoria 8003 Dear Sir/ Madam, Written Submission Economic Regulation of Airports - Productivity Commission Draft (February 2019) This submission highlights that much of the information in the Draft Report is inadequate or incorrect which lead to invalid and socially unacceptable recommendations and conclusions of changing the environmental constraints and associated regulation on Sydney Airport without regard to impact on residents of Sydney. The absence of social and environmental objectives in the study (Draft Report, page 43-44) has lead to the unfair and incorrect conclusions as demonstrated by the inclusion of the aviation lobby issues (relaxing the Cap and Curfew) and not the issues nor the feedback of the community sector submissions which safeguard the quality of life in Sydney for over a million people. The equity objective which was only included in this review for regional NSW's access to Sydney Airport but was not included for the residents under the flight paths. This blatant omission of the equity objective for residents of Sydney has removed any objectivity in the conclusions and recommendations outlined in this report in regard to Sydney Airport. Rather the proposals and recommendations have been supplied by the aviation lobby. If you are going to place an airport in the centre of a city then social, environmental and equity objectives are paramount and MUST over-ride the efficiency objective. Release of this flawed Draft Report resulted in a number of media releases by the aviation lobby advocating for relaxing of the Sydney Airport Cap and Curfew for the benefit of airport efficiency and airline profits with the losers being the residents of Sydney. -

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

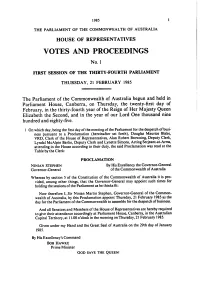

1985 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-FOURTH PARLIAMENT THURSDAY, 21 FEBRUARY 1985 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Thursday, the twenty-first day of February, in the thirty-fourth year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and eighty-five. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of busi- ness pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), Douglas Maurice Blake, VRD, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Alan Robert Browning, Deputy Clerk, Lyndal McAlpin Barlin, Deputy Clerk and Lynette Simons, Acting Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION NINIAN STEPHEN By His Excellency the Governor-General Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia Whereas by section 5 of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia it is pro- vided, among other things, that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit: Now therefore I, Sir Ninian Martin Stephen, Governor-General of the Common- wealth of Australia, by this Proclamation appoint Thursday, 21 February 1985 as the day for the Parliament of the Commonwealth to assemble for the despatch of business. And all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give their attendance accordingly at Parliament House, Canberra, in the Australian Capital Territory, at 11.00 o'clock in the morning on Thursday, 21 February 1985. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

ADDENDA All dates are 1994 unless stated otherwise EUROPEAN UNION. Entry conditions for Austria, Finland and Sweden were agreed on 1 March, making possible these countries' admission on 1 Jan. 1995. ALGERIA. Mokdad Sifi became Prime Minister on 11 April. ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA. At the elections of 8 March the Antigua Labour Party (ALP) gained 11 seats. Lester Bird (ALP) became Prime Minister. AUSTRALIA. Following a reshuffle in March, the Cabinet comprised: Prime Minis- ter, Paul Keating; Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Housing and Regional Development, Brian Howe; Minister for Foreign Affairs and Leader of the Govern- ment in the Senate, Gareth Evans; Trade, Bob McMullan; Defence, Robert Ray; Treasurer, Ralph Willis; Finance and Leader of the House, Kim Beazley; Industry, Science and Technology, Peter Cook; Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, Nick Bolkus; Employment, Education and Training, Simon Crean; Primary Industries and Energy, Bob Collins; Social Security, Peter Baldwin; Industrial Relations and Transport, Laurie Brereton; Attorney-General, Michael Lavarch; Communications and the Arts and Tourism, Michael Lee; Environment, Sport and Territories, John Faulkner; Human Services and Health, Carmen Lawrence. The Outer Ministry comprised: Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, Robert Tickner; Special Minister of State (Vice-President of the Executive Council), Gary Johns; Develop- ment Co-operation and Pacific Island Affairs, Gordon Bilney; Veterans' Affairs, Con Sciacca; Defence Science and Personnel, Gary Punch; Assistant Treasurer, George Gear; Administrative Services, Frank Walker; Small Businesses, Customs and Construction, Chris Schacht; Schools, Vocational Education and Training, Ross Free; Resources, David Beddall; Consumer Affairs, Jeannette McHugh; Justice, Duncan Kerr; Family Services, Rosemary Crowley. -

UNSW Mphil Thesis

Pritchett’s prediction: Australian foreign policy toward Indonesia’s incorporation of East Timor, 1974-1999. Miranda Alice Booth A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences CANBERRA 2017 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 Introduction 4 1.2 Argument of the thesis 10 1.3 Materials and methodology 13 1.4 Literature review 15 1.5 Structure of the thesis 18 CHAPTER 2: AUSTRALIAN FOREIGN POLICY, 1974-1983 20 2.1 The Whitlam Government and Indonesia’s incorporation of Timor, 1974- 75 20 2.2 Pritchett’s challenge 32 2.3 The Balibo Five 37 2.4 The Fraser Government and Indonesia’s invasion of Timor, December 1975-April 1976 41 2.5 Australian foreign policy and public opinion, April 1976 – April 1979 47 2.6 Australia’s recognition of Indonesian sovereignty in Timor 51 CHAPTER 3: AUSTRALIAN FOREIGN POLICY, 1983 – 1996 58 3.1 The 1983 cabinet decision 58 3.2 The Parliamentary Delegation to Timor 61 3.3 Recognising Indonesian sovereignty in Timor 64 3.4 The Santa Cruz massacre 66 3.5 The Keating Government’s foreign policy after Santa Cruz 72 3.6 Australian solidarity after Santa Cruz 77 3.7 Australian foreign policy and public opinion after Santa Cruz 78 CHAPTER 4: AUSTRALIAN FOREIGN POLICY, 1996 – 1999 83 4.1 The Howard Government’s first term, 1996 – 1998 84 4.2 Jakarta’s ‘foreign ally’ 87 4.3 Australian foreign policy and public opinion, 1998 - 1999 88 4.4 Containing international pressure 97 2 4.5 ‘Scorched Earth’ 100 4.6 The solidarity movement in action -

Factions and Fractions: a Case Study of Power Politics in the Australian Labor Party

Australian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 427– 448 Factions and Fractions: A Case Study of Power Politics in the Australian Labor Party ANDREW LEIGH Of ce of the Shadow Minister for Trade, Canberra Over the past three decades, factions have cemented their hold over the Australian Labor Party. This has largely been due to the entrenchment of the proportional representation of factions. One of the effects of the institutionalisa- tion of factions has been the development of factional sub-groupings (‘frac- tions’). This article analyses the phenomenon by looking at a case study of a single ALP faction—the Left in New South Wales. Since 1971, two major fractions have developed in the NSW Left, based on ideological disagreements, personality con icts, generational differences and arguments over the role of the union movement in the ALP. This development parallels the intra-factional splits that have occurred in many other sections of the Labor Party. Yet the factional system in the 1980s and 1990s operated relatively effectively as a means of managing power. The question now is whether it can survive the challenge of new issues that cross-cut traditional ideological lines. Introduction Factionalism in the Australian Labor Party (ALP) is a phenomenon much remarked upon, but little analysed. Like the role of the Ma a in Italian politics, few outside the system seem to understand the power networks, whilst few inside are prepared to share their thoughts with the outside world. Yet without understanding factions, it is impossible to properly comprehend the Labor Party. Every organisation, and certainly every political party, contains organised power groupings. -

The Cyprus Issue in Australian Politics: PASEKA & SEKA (SA) Perspectives

GANZIS.qxd 15/1/2001 2:42 ìì Page 93 Ganzis, Nicholas 2003. The Cyprus Issue in Australian Politics: PASEKA & SEKA (SA) Perspectives. In E. Close, M. Tsianikas and G. Frazis (Eds.) “Greek Research in Australia: Proceedings of the Fourth Biennial Conference of Greek Studies, Flinders University, September 2001”. Flinders University Department of Languages – Modern Greek: Adelaide, 93-114. The Cyprus Issue in Australian Politics: PASEKA & SEKA (SA) Perspectives Nicholas Ganzis While the ALP supported the decolonisation and independence of Cyprus in the 1950s, the Menzies Liberal-Country Party coalition government, with the escalation of the Cold War, condemned Cypriot freedom fighters of the late 1950s as terrorists. However, Menzies commitment to mutual Anglo- Australian loyalty and Commonwealth cohesion led him, on Britains rec- ommendation, to accept Cyprus as a fellow Commonwealth member once it gained its independence in 1960, as this suited Britains vested interests (Goldsworthy, 1997:1048). The relationship between the two major ethnic groups in Cyprus (Greek and Turkish Cypriots) was difficult and problematic from the outset and con- flict broke out between the two groups in 1963. Australia supported the es- tablishment of a UN peacekeeping force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) on 4 March 1964. On 24 April 1964 Menzies offered Australias participation in the peacekeeping force (Brown, Barker & Burke, 1984:1222). A civilian police contingents operations as part of UNFICYP began in 1964 (Clark, 1980:16061). Labor willingly continued this policy (Åvans, 1993:11 and 103). As many Greeks, Greek Cypriots and Turks had come to Australia, the events in Cyprus in 1974 opened the way for newer influences on Australias foreign policy (Whitlam, 1986:126; Jupp, 1983:4043). -

Political Chronicles the Commonwealth of Australia

Australian Journal of Politics and History: Volume 50, Number 4, 2004, pp. 588-639. Political Chronicles The Commonwealth of Australia January to June 2004 PAUL D. WILLIAMS Politics and Public Policy, Griffith University The first half of 2004 saw newly installed Labor leader, Mark Latham, carve out a distinctive — if quasi-populist — leadership style while also exerting upon John Howard a heightened level of public questioning as to the honesty of his Government. Indeed, the Prime Minister had never appeared more “rattled”. The politics of personal abuse then plumbed new depths as each leader defended his integrity. The major parties’ public opinion standing fluctuated accordingly. A generous Government Budget was matched by Labor’s flight of numerous populist policy kites that saw election speculation become a journalistic sport. National Economy The Australian economy was at no time a liability for the Government. In March, national growth topped an annual rate of 4 per cent. After falling to a 23 year low of 5.5 per cent, the unemployment rate closed the period at 5.7 per cent, while inflation, too, remained low at an annual rate, by June, of 2.5 per cent. Housing costs largely dominated economic discussion, with a general agreement the housing “bubble” had at last burst. January alone saw a 10 per cent decline in home loan approvals (Weekend Australian, 13-14 March 2004). When, in April, the Productivity Commission released its report into housing affordability, few were surprised when it found that “negative gearing” was largely responsible. The Commission’s recommendation to review generous investor tax breaks was ignored by the Treasurer.