LIP15 Kelly Design.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004000444.Pdf

Copyright of Full Textrests with theoriginal copyright owner and, except as permitted under the CopyrightAct 1968,copyingthiscopyrightmaterial is prohibited without thepennission of theowner or itsexclusive licensee oragent orbywayofa licence 200408342 from Copyright Agency Limited. For information about suchlicences contact Copyright Agency Limitedon (02) 93947600(ph) 0,(02) 93947601 (fax) Stories in distress: Three case studies in Australian media coverage of humanitarian crises Wendy Bacon and Chris Nash Abstract This article reviews three case studies in the Australian media reporting ofinternational humanitarian crises. The case studies cover a six-month period in 1999 and draw on all media over that period. The three case studies are: the violence in East TImor at the time ofthe 1999 independence ballot, the imprisonment in Yugoslavia of Prall and Wallace, two employees of CARE Australia, and the floods in Mozambique. While the three case studies collectively exhibit many ofthe standard characteristics ofmedia coverage ofhumanitarian issues, individually they dif fer significantly in the scale andorientation ofcoverage. Wesug gest that a significantfactor in these differences was the relation ship between the sources for the stories and the journalists, which in turn depended on other factors. We review the adequa cy of the Hall and Ericson positions on the source-journalist relationship in explaining these differences, and suggest that a field analysis derivedfrom Bourdieu is helpful in explaining the involvement ofsources from the political, economic and military fields, which in turn impacted on the relationship ofthe media to the stories. Introduction On December 27, 2003, while many people in the Western world were enjoying their Christmas holidays, more than 40,000 Iranians were killed in an earthquake in the ancient city of Bam. -

Media Locks in the New Narrative

7. Influences on a changed story and the new normal: media locks in the new narrative It was the biggest, most powerful spin campaign in Australian media history—the strategy was to delay action on greenhouse gas emissions until ‘coal was ready’—with geo-sequestration (burying carbon gases) and tax support. Alan Tate, ABC environment reporter 1990s On 23 September 2013 the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) program Media Watch explored a textbook example of why too many Australians and their politicians continue to stumble through a fog of confusion and doubt in regard to climate change. The case under the microscope typified irresponsible journalism. Media Watch host Paul Barry, with trademark irony, announced: ‘Yes it’s official at last … those stupid scientists on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC] got it wrong’, in their latest assessment report. He quoted 2GB breakfast jock Chris Smith from a week earlier saying the IPCC had ‘fessed up’ that its computers had drastically overestimated rising temperatures. ‘That’s a relief,’ said Barry, and how do we know this? ‘Because Chris Smith read it on the front page of last Monday’s Australian newspaper. When it comes to rubbishing the dangers of man-made global warming the shock jocks certainly know who they can trust.’ But wait. The Australian’s story by Environment Editor Graham Lloyd—‘We got it wrong on warming says IPCC’ was not original either. According to Media Watch, Lloyd appeared to have based his story on a News Limited sister publication from the United Kingdom. Said Barry: ‘He’d read all about it in the previous day’s Mail on Sunday,’ which had a story headlined ‘The great green con’. -

Jim Molan Biography

Jim Molan Biography Retiring from the Australian Army in July 2008 after 40 years, Jim Molan served across a broad range of command and staff appointments in operations, training, staff and military diplomacy. Jim has been an infantryman, an Indonesian speaker, a helicopter pilot, commander of army units from a thirty man platoon to a division of 15,000 soldiers, commander of the Australian Defence Colleges and commander of the evacuation force from the Solomon Islands in 2000. He has served in Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, East Timor, Malaysia, Germany, the US and Iraq. In April 2004, Major General Molan deployed for a year to Iraq as the Coalition’s chief of operations, during a period of continuous and intense combat. On behalf of the US commanding general, he controlled the manoeuvre operations of all forces across all of Iraq, including the security of Iraq’s oil, electricity and rail infrastructure. This period covered the Iraqi elections in January 2005, and the pre-election shaping battles of Najaf, TalAfar, Samarra, Fallujah, and Ramadan 04. Described in the recently (2017) declassified ‘unofficial history’ of ‘Australia’s Participation in the Iraq War’ as “… the ADF member most directly involved in fighting the insurgents”, Major General Molan was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross by the Australian Government for “distinguished command and leadership in action in Iraq”, and the Legion of Merit by the United States Government. Before retiring he was the Adviser to the Vice Chief of the Defence Force on Joint Warfighting and the first Defence Materiel Advocate, promoting Australian defence industry overseas. -

The Tocsin | Issue 12, 2021

Contents The Tocsin | Issue 12, 2021 Editorial – Shireen Morris and Nick Dyrenfurth | 3 Deborah O’Neill – The American Warning | 4 Kimberley Kitching – Super Challenges | 7 Kristina Keneally – Words left unspoken | 10 Julia Fox – ‘Gender equality is important but …’ | 12 In case you missed it ... | 14 Clare O’Neil – Digital Dystopia? | 16 Amanda Rishworth – Childcare is the mother and father of future productivity gains | 18 Shireen Morris – Technology, Inequality and Democratic Decline | 20 Robynne Murphy – How women took on a giant and won | 24 Shannon Threlfall-Clarke – Front of mind | 26 The Tocsin, Flagship Publication of the John Curtin Research Centre. Issue 12, 2021. Copyright © 2021 All rights reserved. Editor: Nick Dyrenfurth | [email protected] www.curtinrc.org www.facebook.com/curtinrc/ twitter.com/curtin_rc Editorial Executive Director, Dr Nick Dyrenfurth Committee of Management member, Dr Shireen Morris It was the late, trailblazing former Labor MP and Cabinet Minister, Susan Ryan, who coined the memorable slogan ‘A must be identified and addressed proactively. We need more Woman’s Place is in the Senate’. In 1983, Ryan along with talented female candidates being preselected in winnable seats. Ros Kelly were among just four Labor women in the House of We need more female brains leading in policy development Representatives, together with Joan Child and Elaine Darling. and party reform, beyond the prominent voices on the front As the ABC notes, federal Labor boasts more than double the bench. We need to nurture new female talent, particularly number of women in Parliament and about twice the number women from working-class and migrants backgrounds. -

Australian Institute of International Affairs National Conference

Australian Institute of International Affairs National Conference Australian Foreign Policy: Navigating the New International Disorder Monday 21 November 2016 Hotel Realm Canberra, National Circuit, Barton Arrival 8:30 – 9:00am Australian Foreign Policy 9:00am – 11:00am The Hon Julie Bishop MP (Invited) Minister for Foreign Affairs Julie Bishop is the Minister for Foreign Affairs in Australia's Federal Coalition Government. She is also the Deputy Leader of the Liberal Party and has served as the Member for Curtin since 1998. Minister Bishop was sworn in as Australia's first female Foreign Minister on 18 September 2013 following four years in the role of Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade. She previously served as a Cabinet Minister in the Howard Government as Minister for Education, Science and Training and as the Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Women's Issues. Prior to this, Minister Bishop was Minister for Ageing. Minister Bishop has also served on a number of parliamentary and policy committees including as Chair of the Joint Standing Committee on Treaties. Before entering Parliament Minister Bishop was a commercial litigation lawyer at Perth firm Clayton Utz, becoming a partner in 1985, and managing partner in 1994. The Hon Kim Beazley AC FAIIA AIIA National President Mr Beazley was elected to the Federal Parliament in 1980 and represented the electorates of Swan (1980-96) and Brand (1996- 2007). Mr Beazley was a Minister in the Hawke and Keating Labor Governments (1983-96) holding, at various times, the portfolios of Defence, Finance, Transport and Communications, Employment Education and Training, Aviation, and Special Minister of State. -

Juila Gillard, 45, Says the Problem for Women in Politics Is That There Is Not a Set Image of What a Woman Leader Should Look Like

Juila Gillard, 45, says the problem for women in politics is that there is not a set image of what a woman leader should look like. Men, she says, simply get better-quality suits, shirts and ties. ‘Women have so many more options it’s easier to criticise,’ she says. ‘You have to take it with a grain of salt and a fair bit of good humour.’ in profi le JULIA GILLARD From hostel to HISTORY She’s one of our most senior female politicians and one day she could have the top job. But what’s she really like? JULIE McCROSSIN meets Julia Gillard f you want to get to know Julia Gillard There is no sign of that clipped, robotic the White House, where people rarely sleep and understand what drives her political voice that often appears in her sound-bites or go home, has a lot in common with her Ipassions, you have to know the story of on the news. If she gets the chance to talk a life in parliament. her Welsh immigrant family, especially that of bit longer, as she does these days in the chatty There’s not much spare space in her offi ce, her father, John. world of breakfast television with her regular meeting room and en-suite bathroom. The It’s been a long journey from the appearances on Nine’s Today show debating window offers a glimpse of a courtyard Pennington Migrant Hostel in Adelaide, the Liberal Party’s heavyweight Tony Abbott, with trees. Aboriginal art by Maggie Long where Gillard arrived in 1966 at age four with you hear a more natural voice. -

Apo-Nid63005.Pdf

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 1991-92 Australian Broadcasting Tribunal Sydney 1992 ©Commonwealth of Australia ISSN 0728-8883 Design by Media and Public Relations Branch, Australian Broadcasting Tribunal. Printed in Australia by Pirie Printers Sales Pty Ltd, Fyshwick, A.CT. 11 Contents 1. MEMBERSIDP OF THE TRIBUNAL 1 2. THE YEAR IN REVIEW 7 3. POWERS AND FUNCTIONS OF THE TRIBUNAL 13 Responsible Minister 16 4. LICENSING 17 Number and Type of Licences on Issue 19 Grant of Limited Licences 20 Commercial Radio Licence Grant Inquiries 21 Supplementary Radio Grant Inquiries 23 Joined Supplementary /Independent Radio Grant Inquiries 24 Remote Licences 26 Public Radio Licence Grants 26 Renewal of Licences with Conditions or Licensee Undertaking 30 Revocation/Suspension/Conditions Inquiries 32 Allocation of Call Signs 37 5. OWNERSHIP AND CONTROL 39 Applications and Notices Received 41 Most Significant Inquiries 41 Unfinished Inquiries 47 Contraventions Amounting To Offences 49 Licence Transfers 49 Uncompleted Inquiries 50 Operation of Service by Other than Licensee 50 Registered Lender and Loan Interest Inquiries 50 6. PROGRAM AND ADVERTISING STANDARDS 51 Program and Advertising Standards 53 Australian Content 54 Compliance with Australian Content Television Standard 55 Children's Television Standards 55 Compliance with Children's Standards 58 Comments and Complaints 59 Broadcasting of Political Matter 60 Research 61 iii 7. PROGRAMS - PUBLIC INQUIRIES 63 Public Inquiries 65 Classification of Television Programs 65 Foreign Content In Television Advertisements 67 Advertising Time On Television 68 Film And Television Co-productions 70 Australian Documentary Programs 71 Cigarette Advertising During The 1990 Grand Prix 72 Test Market Provisions For Foreign Television Advertisements 72 Public Radio Sponsorship Announcements 73 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles 74 John Laws - Comments About Aborigines 75 Anti-Discrimination Standards 75 Accuracy & Fairness in Current Affairs 76 Religious Broadcasts 77 Review of Classification Children's Television Programs 78 8. -

The Australian, Argues That “The Cause of Aboriginal Welfare

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository 1 “Black Armband” versus “White Blindfold” History in Australia: A Review Essay Patrick Brantlinger In The Australian for September 18, 2003, Greg Sheridan writes that “the cause of Aboriginal welfare and the quality of Australian political culture have been seriously damaged by the moral and linguistic overkill” of those historians who claim that “genocide” is an accurate term for what happened during the European colonization of that continent. He is seconding the current prime minister, John Howard, who has publicly declared that he wishes the historians would stop “using outrageous words like genocide” (qtd. in Reynolds, Indelible Stain 2). Sheridan thinks that “the past mistreatment of Aborigines is the most serious moral failing in our history,” but that it “never approached genocide or had any relationship to genocide.” Academics of “a certain left-wing cast of mind” engage both in pedantic, “linguistic” hairsplitting over definitions of such loaded words as “genocide” (a “jargon word,” according to Sheridan) and use those same words with gross, hyperbolic inaccuracy. Sheridan knows this is the case because “all dictionaries give [it] the same meaning.” And that meaning, according to his “Penguin dictionary,” is: “the mass murder of a racial, national or religious group.” This, Sheridan believes, never occurred in Australia, even though he also believes that “substantial numbers of Aborigines were killed by white settlers and British authorities in Tasmania and in Australia generally….” Apparently, he spies some clear difference Transnational Seminar, October 15th, 2004, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. -

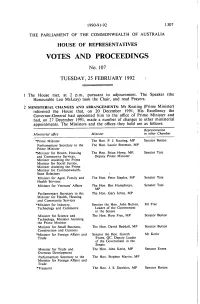

Votes and Proceedings

1990-91-92 1307 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 107 TUESDAY, 25 FEBRUARY 1992 1 The House met, at 2 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. The Speaker (the Honourable Leo McLeay) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 MINISTERIAL CHANGES AND ARRANGEMENTS: Mr Keating (Prime Minister) informed the House that, on 20 December 1991, His Excellency the Governor-General had appointed him to the office of Prime Minister and had, on 27 December 1991, made a number of changes to other ministerial appointments. The Ministers and the offices they hold are as follows: Representation Ministerial office Minister in other Chamber *Prime Minister The Hon. P. J. Keating, MP Senator Button Parliamentary Secretary to the The Hon. Laurie Brereton, MP Prime Minister *Minister for Health, Housing The Hon. Brian Howe, MP, Senator Tate and Community Services, Deputy Prime Minister Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Social Justice, Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Commonwealth- State Relations I Minister for Aged, Family and The Hon. Peter Staples, MP Senator Tate Health Services Minister for Veterans' Affairs The Hon. Ben Humphreys, Senator Tate MP Parliamentary Secretary to the The Hon. Gary Johns, MP Minister for Health, Housing and Community Services *Minister for Industry, Senator the Hon. John Button, Mr Free Technology and Commerce Leader of the Government in the Senate Minister for Science and The Hon. Ross Free, MP Senator Button Technology, Minister Assisting the Prime Minister Minister for Small Business, The Hon. David Beddall, MP Senator Button Construction and Customs *Minister for Foreign Affairs and Senator the Hon. -

Howard Government Retrospective II

Howard Government Retrospective II “To the brink: 1997 - 2001” Articles by Professor Tom Frame 14 - 15 November 2017 Howard Government Retrospective II The First and Second Howard Governments Initial appraisals and assessments Professor Tom Frame Introduction I have reviewed two contemporaneous treatments Preamble of the first Howard Government. Unlike other Members of the Coalition parties frequently complain retrospectives, these two works focussed entirely on that academics and journalists write more books about the years 1996-1998. One was published in 1997 the Australian Labor Party (ALP) than about Liberal- and marked the first anniversary of the Coalition’s National governments and their leaders. For instance, election victory. The other was published in early three biographical studies had been written about Mark 2000 when the consequences of some first term Latham who was the Opposition leader for a mere decisions and policies were becoming a little clearer. fourteen months (December 2003 to February 2005) Both books are collections of essays that originated when only one book had appeared about John Howard in university faculties and concentrated on questions and he had been prime minister for nearly a decade. of public administration. The contributions to both Certainly, publishers believe that books about the Labor volumes are notable for the consistency of their tone Party (past and present) are usually more successful and tenor. They are not partisan works although there commercially than works on the Coalition parties. The is more than a hint of suspicion that the Coalition sales figures would seem to suggest that history and was tampering with the institutions that undergirded ideas mean more to some Labor followers than to public authority and democratic government in Coalition supporters or to Australian readers generally. -

The Life and Adventures of Malcolm Turnbull Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STOP AT NOTHING: THE LIFE AND ADVENTURES OF MALCOLM TURNBULL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Annabel Crabb | 208 pages | 18 May 2016 | Black Inc. | 9781863958189 | English | Melbourne, Australia Stop at Nothing: The Life and Adventures of Malcolm Turnbull PDF Book Without that a lot of it wont make sense, and relevance would also be limited. I am now much more inclined towards the Australian Conservatives rather than the Liberals. Quarterly Essay 34 Stop At Nothing. Craig Dowling rated it it was amazing Oct 09, I recommend this to anyone looking for a way to begin understanding the forces at work in Australian politics. Maybe I was looking for something different in the book did not find it enlightening at all first book I have read of Annabelle Crabb. Easy and enjoyable read - even for people who are not naturally liberal fans. Drawing on extensive interviews with Turnbull, Crabb delves into his university exploits — which included co-authoring a musical with Bob Ellis — and his remarkable relationship with Kerry Packer, the man for whom he was first a prized attack dog and then a mortal enemy. Bron rated it it was ok Dec 30, At times, the Turnbull life-story seems almost to have the silvery impermanence of cinema, and you suspect that somewhere behind it all is a haggard old-time Hollywood screenwriter, artfully inserting plot twists and complex little synchronicities for the benefit of the audience. Anyway, I I never really looked into the politics of my own country that much - America is just so much crazier and more sensational. This book, slightly longer than a quarterly essay, is worth an afternoon of your time. -

Ministerial Staff Under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution Or Black Hole?

Ministerial Staff Under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution or Black Hole? Author Tiernan, Anne-Maree Published 2005 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Department of Politics and Public Policy DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3587 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367746 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Ministerial Staff under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution or Black Hole? Anne-Maree Tiernan BA (Australian National University) BComm (Hons) (Griffith University) Department of Politics and Public Policy, Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2004 Abstract This thesis traces the development of the ministerial staffing system in Australian Commonwealth government from 1972 to the present. It explores four aspects of its contemporary operations that are potentially problematic. These are: the accountability of ministerial staff, their conduct and behaviour, the adequacy of current arrangements for managing and controlling the staff, and their fit within a Westminster-style political system. In the thirty years since its formal introduction by the Whitlam government, the ministerial staffing system has evolved to become a powerful new political institution within the Australian core executive. Its growing importance is reflected in the significant growth in ministerial staff numbers, in their increasing seniority and status, and in the progressive expansion of their role and influence. There is now broad acceptance that ministerial staff play necessary and legitimate roles, assisting overloaded ministers to cope with the unrelenting demands of their jobs. However, recent controversies involving ministerial staff indicate that concerns persist about their accountability, about their role and conduct, and about their impact on the system of advice and support to ministers and prime ministers.