January 2015 Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phase Evolution of Ancient and Historical Ceramics

EMU Notes in Mineralogy, Vol. 20 (2019), Chapter 6, 233–281 The struggle between thermodynamics and kinetics: Phase evolution of ancient and historical ceramics 1 2 ROBERT B. HEIMANN and MARINO MAGGETTI 1Am Stadtpark 2A, D-02826 Go¨rlitz, Germany [email protected] 2University of Fribourg, Dept. of Geosciences, Earth Sciences, Chemin du Muse´e6, CH-1700 Fribourg, Switzerland [email protected] This contribution is dedicated to the memory of Professor Ursula Martius Franklin, a true pioneer of archaeometric research, who passed away at her home in Toronto on July 22, 2016, at the age of 94. Making ceramics by firing of clay is essentially a reversal of the natural weathering process of rocks. Millennia ago, potters invented simple pyrotechnologies to recombine the chemical compounds once separated by weathering in order to obtain what is more or less a rock-like product shaped and decorated according to need and preference. Whereas Nature reconsolidates clays by long-term diagenetic or metamorphic transformation processes, potters exploit a ‘short-cut’ of these processes that affects the state of equilibrium of the system being transformed thermally. This ‘short-cut’ is thought to be akin to the development of mineral-reaction textures resulting from disequilibria established during rapidly heated pyrometamorphic events (Grapes, 2006) involving contact aureoles or reactions with xenoliths. In contrast to most naturally consolidated clays, the solidified rock-like ceramic material inherits non-equilibrium and statistical states best described as ‘frozen-in’. The more or less high temperatures applied to clays during ceramic firing result in a distinct state of sintering that is dependent on the firing temperature, the duration of firing, the firing atmosphere, and the composition and grain-size distribution of the clay. -

'A Mind to Copy': Inspired by Meissen

‘A Mind to Copy’: Inspired by Meissen Anton Gabszewicz Independent Ceramic Historian, London Figure 1. Sir Charles Hanbury Williams by John Giles Eccardt. 1746 (National Portrait Gallery, London.) 20 he association between Nicholas Sprimont, part owner of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, Sir Everard Fawkener, private sec- retary to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the second son of King George II, and Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, diplomat and Tsometime British Envoy to the Saxon Court at Dresden was one that had far-reaching effects on the development and history of the ceramic industry in England. The well-known and oft cited letter of 9th June 1751 from Han- bury Williams (fig. 1) to his friend Henry Fox at Holland House, Kensington, where his china was stored, sets the scene. Fawkener had asked Hanbury Williams ‘…to send over models for different Pieces from hence, in order to furnish the Undertakers with good designs... But I thought it better and cheaper for the manufacturers to give them leave to take away any of my china from Holland House, and to copy what they like.’ Thus allowing Fawkener ‘… and anybody He brings with him, to see my China & to take away such pieces as they have a mind to Copy.’ The result of this exchange of correspondence and Hanbury Williams’ generous offer led to an almost instant influx of Meissen designs at Chelsea, a tremendous impetus to the nascent porcelain industry that was to influ- ence the course of events across the industry in England. Just in taking a ca- sual look through the products of most English porcelain factories during Figure 2. -

Grand Tour of European Porcelain

Grand Tour of European Porcelain Anna Calluori Holcombe explores the major European porcelain centres Left: Gilder. Bernardaud Factory. embarked on a modern version of the 17th and 18th century Grand Limoges, France. Tour of Europe in summer of 2010 and spent two months researching Right: Designer table setting display. porcelain (primarily tableware) from historical and technical per- Bernardaud Factory. Limoges, France. Photos by Anna Calluori Holcombe. Ispectives. The tradition of Grand Tour promoted the idea of travelling for the sake of curiosity and learning by travelling through foreign lands. On a research leave with a generous Faculty Enhancement Grant A factory was started in 1863 by some investors and, at about from the University of Florida (UF), I visited factories and museums in that time, an apprentice was hired 10 major European ceramics centres. named Léonard Bernardaud. He Prior to this interest in investigating European porcelain, I spent time worked his way up to become a studying Chinese porcelains with fascination and awe. On one of my partner, then acquiring the company in 1900 and giving it his name. many trips to China and my first visit to the famous city of Jingdezhen, I In 1949, the factory introduced climbed Gaoling Mountain, where the precious kaolin that is essential to the first gas-fuelled tunnel kiln in the Chinese porcelain formula was first mined more than 1000 years ago. France operated 24 hours a day, a Soft paste porcelain, which does not have the durability and translu- standard in most modern factories today. Although they had to cut 15 cency found in hard paste porcelain was in popular use in Europe prior percent of their employees in recent to their discovery of hard paste porcelain. -

A Detective Story: Meissen Porcelains Copying East Asian Models. Fakes Or Originals in Their Own Right?

A detective story: Meissen porcelains copying East Asian models. Fakes or originals in their own right? Julia Weber, Keeper of Ceramics at the Bavarian National Museum, Munich he ‘detective story’ I want to tell relates to how the French mer- fact that Saxon porcelain was the first in Europe to be seriously capable of chant Rodolphe Lemaire managed, around 1730, to have accurate competing with imported goods from China and Japan. Indeed, based on their copies of mostly Japanese porcelain made at Meissen and to sell high-quality bodies alone, he appreciated just how easily one might take them them as East Asian originals in Paris. I will then follow the trail of for East Asian originals. This realisation inspired Lemaire to embark on a new Tthe fakes and reveal what became of them in France. Finally, I will return business concept. As 1728 drew to a close, Lemaire travelled to Dresden. He briefly to Dresden to demonstrate that the immediate success of the Saxon bought Meissen porcelains in the local warehouse in the new market place copies on the Parisian art market not only changed how they were regarded and ordered more in the manufactory. In doing this he was much the same in France but also in Saxony itself. as other merchants but Lemaire also played a more ambitious game: in a bold Sometime around 1728, Lemaire, the son of a Parisian family of marchand letter he personally asked Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony and of faïencier, became acquainted with Meissen porcelain for the first time whilst Poland, to permit an exclusive agreement with the Meissen manufactory. -

Meissen Porcelain: Precision, Presentation, and Preservation

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 Meissen Porcelain: Precision, Presentation, and Preservation. How Artistic and Technological Significance Influence Conservation Protocol Nicole Peters West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Peters, Nicole, "Meissen Porcelain: Precision, Presentation, and Preservation. How Artistic and Technological Significance Influence Conservation Protocol" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 756. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/756 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Meissen Porcelain: Precision, Presentation, and Preservation. How Artistic and Technological Significance Influence Conservation Protocol. Nicole Peters Thesis submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Approved by Janet Snyder, Ph.D., Committee Chair Rhonda Reymond, Ph.D. Jeff Greenham, M.F.A. Michael Belman, M.S. Division of Art and Design Morgantown, West Virginia 2011 Keywords: Meissen porcelain, conservation, Fürstenzug Mural, ceramic riveting, material substitution, object replacement Copyright 2011 Nicole L. -

Meissen Masterpieces Exquisite and Rare Porcelain Models from the Royal House of Saxony to Be Offered at Christie’S London

For Immediate Release 30 October 2006 Contact: Christina Freyberg +44 20 7 752 3120 [email protected] Alexandra Kindermann +44 20 7 389 2289 [email protected] MEISSEN MASTERPIECES EXQUISITE AND RARE PORCELAIN MODELS FROM THE ROYAL HOUSE OF SAXONY TO BE OFFERED AT CHRISTIE’S LONDON British and Continental Ceramics Christie’s King Street Monday, 18 December 2006 London – A collection of four 18th century Meissen porcelain masterpieces are to be offered for sale in London on 18 December 2006 in the British and Continental Ceramics sale. This outstanding Meissen collection includes two white porcelain models of a lion and lioness (estimate: £3,000,000-5,000,000) and a white model of a fox and hen (estimate: £200,000-300,000) commissioned for the Japanese Palace in Dresden together with a white element vase in the form of a ewer (£10,000-15,000). “The porcelain menagerie was an ambitious and unparalleled project in the history of ceramics and the magnificent size of these models is a testament to the skill of the Meissen factory,” said Rodney Woolley, Director and Head of European Ceramics. “The sheer exuberance of these examples bears witness to the outstanding modelling of Kirchner and Kändler. The opportunity to acquire these Meissen masterpieces from the direct descendants of Augustus the Strong is unique and we are thrilled to have been entrusted with their sale,” he continued. The works of art have been recently restituted to the heirs of the Royal House of Saxony, the Wettin family. Commenting on the Meissen masterpieces, a spokesperson for the Royal House of Saxony said: “The Wettin family has worked closely, and over many years with the authorities to achieve a successful outcome of the restitution of many works of art among which are these four Meissen porcelain objects, commissioned by our forebear Augustus the Strong. -

Volume 18 (2011), Article 3

Volume 18 (2011), Article 3 http://chinajapan.org/articles/18/3 Lim, Tai Wei “Re-centering Trade Periphery through Fired Clay: A Historiography of the Global Mapping of Japanese Trade Ceramics in the Premodern Global Trading Space” Sino-Japanese Studies 18 (2011), article 3. Abstract: A center-periphery system is one that is not static, but is constantly changing. It changes by virtue of technological developments, design innovations, shifting centers of economics and trade, developmental trajectories, and the historical sensitivities of cultural areas involved. To provide an empirical case study, this paper examines the material culture of Arita/Imari 有田/伊万里 trade ceramics in an effort to understand the dynamics of Japan’s regional and global position in the transition from periphery to the core of a global trading system. Sino-Japanese Studies http://chinajapan.org/articles/18/3 Re-centering Trade Periphery through Fired Clay: A Historiography of the Global Mapping of Japanese Trade Ceramics in the 1 Premodern Global Trading Space Lim Tai Wei 林大偉 Chinese University of Hong Kong Introduction Premodern global trade was first dominated by overland routes popularly characterized by the Silk Road, and its participants were mainly located in the vast Eurasian space of this global trading area. While there are many definitions of the Eurasian trading space that included the so-called Silk Road, some of the broadest definitions include the furthest ends of the premodern trading world. For example, Konuralp Ercilasun includes Japan in the broadest definition of the silk route at the farthest East Asian end.2 There are also differing interpretations of the term “Silk Road,” but most interpretations include both the overland as well as the maritime silk route. -

01-32 Errol Manner Pages

E & H MANNERS E & H MANNERS A Selection from THE NIGEL MORGAN COLLECTION OF ENGLISH PORCELAIN THE NIGEL MORGAN COLLECTION THE NIGEL MORGAN E & H MANNERS E & H MANNERS A Selection from THE NIGEL MORGAN COLLECTION of ENGLISH PORCELAIN incorporating The collection of Eric J. Morgan and Dr F. Marian Morgan To be exhibited at THE INTERNATIONAL CERAMICS FAIR AND SEMINAR 11th to the 14th of JUNE 2009 Catalogue by Anton Gabszewicz and Errol Manners 66C Kensington Church Street London W8 4BY [email protected] www.europeanporcelain.com 020 7229 5516 NIGEL MORGAN O.A.M. 1938 – 2008 My husband’s parents Eric J. Morgan and Dr Marian Morgan of Melbourne, Australia, were shipwrecked off the southernmost tip of New Zealand in 1929 losing everything when their boat foundered (except, by family legend, a pair of corsets and an elaborate hat). On the overland journey to catch another boat home they came across an antique shop, with an unusual stock of porcelain. That day they bought their first piece of Chelsea. They began collecting Oriental bronzes and jades in the 1930s – the heady days of the sale of the dispersal of the Eumorfopoulos Collections at Bluett & Sons. On moving to England in the 1950s and joining the English Ceramic Circle in 1951, their collecting of English porcelain gathered pace. Nigel, my husband, as the child of older parents, was taken around museums and galleries and began a life-long love of ceramics. As a small boy he met dealers such as Winifred Williams, whose son Bob was, in turn, a great mentor to us. -

Recommended Sights in and Around Dresden1

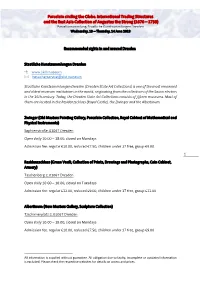

Porcelain circling the Globe. International Trading Structures and the East Asia Collection of Augustus the Strong (1670 – 1733) Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Wednesday, 13 – Thursday, 14 June 2018 Recommended sights in and around Dresden1 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden www.skd.museum [email protected] Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections) is one of the most renowned and oldest museum institutions in the world, originating from the collections of the Saxon electors in the 16th century. Today, the Dresden State Art Collections consists of fifteen museums. Most of them are located in the Residenzschloss (Royal Castle), the Zwinger and the Albertinum. Zwinger (Old Masters Painting Gallery, Porcelain Collection, Royal Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments) Sophienstraße, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 1 Residenzschloss (Green Vault, Collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, Coin Cabinet, Armory) Taschenberg 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Tuesdays Admission fee: regular €12.00, reduced €9.00, children under 17 free, group €11.00 Albertinum (New Masters Gallery, Sculpture Collection) Tzschirnerplatz 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 All information is supplied without guarantee. All obligation due to faulty, incomplete or outdated -

February 2018 Newsletter

San Francisco Ceramic Circle An Affiliate of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco February 2018 P.O. Box 26773, San Francisco, CA 94126 www.patricianantiques.com/sfcc.html SFCC FEBRUARY LECTURE A Glittering Occasion: Reflections on Dining in the 18th Century Sunday, FEBRUARY 25, 2017 9:45 a.m., doors open for social time Dr. Christopher Maxwell 10:30 a.m., program begins Curator of European Glass Gunn Theater, Legion of Honor Corning Museum of Glass About the lecture: One week later than usual, in conjunction with the Casanova exhibition at the Legion of Honor, the lecture will discuss the design and function of 18th-century tableware. It will address the shift of formal dining from daylight hours to artificially lit darkness. That change affected the design of table articles, and the relationship between ceramics and other media. About the speaker: Dr. Christopher L. Maxwell worked on the redevelopment of the ceramics and glass galleries at the Victoria and Albert Museum, with a special focus on 18th-century French porcelain. He also wrote the V&A’s handbook Eighteenth-Century French Porcelain (V&A Publications, 2010). From 2010 to 2016 he worked with 18th-century decorative arts at the Royal Collections. He has been Curator of European Glass at the Corning Museum of Glass since 2016. Dr. Maxwell is developing an exhibition proposal on the experience of light and reflectivity in 18th-century European social life. This month, our Facebook page will show 18th-century table settings and dinnerware. The dining room at Mount Vernon, restored to the 1785 color scheme of varnished dark green walls George Washington’s Mount Vernon, VA (photo: mountvernon.org SFCC Upcoming Lectures SUNDAY, MARCH 18, Gunn Theater: Gunn Theater: Jody Wilkie, Co-Chairman, Decorative Arts, and Director, Decorative Arts of the Americas, Christie’s: “Ceramics from the David Rockefeller collection.” SUNDAY, APRIL 15, Sally Kevill-Davies, cataloguer of the English porcelain at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, will speak on Chelsea porcelain figures. -

Arta Contemporană

Arta contemporană Johannis TSOUMAS Examining the influence of Japanese culture on the form and decoration of the early Meissen porcelain objects doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3938557 Summary Examining the influence of Japanese culture on the form and decoration of the early Meissen porcelain objects The aim of this research is to examine how Japanese porcelain interacted with the European porcelain in- vented in the early eighteenth century Germany, creating a novel type of utility wares and decorative objects which conquered not only the markets but also the courts of Europe. Exploring how Japanese porcelain forms and motifs created narratives after being introduced by the Portuguese missionaries and the Dutch merchants in the sixteenth and the seventeenth century, the researcher will try to point out the importance of Japanese culture in a worldwide context, and its contribution to the growing interest of the European porcelain makers, artists and trad- ers. He will also focus on the profound interest in Japanese culture, restricted to the area of Japanese ceramics and particularly porcelain wares, exploring, at the same time, when and how Japanese objects surpassed the Chinese products which had been very popular on European markets a long time before. Other questions to be answered are about the remaking of small Japanese-like figures which contributed to the Europe’s fashion frenzy for some other types of hard-paste porcelain objects such as the large-scale statues and figurines, initially made in the 1720’s and 1730’s, but also the Imari and Kakiemon style wares made for the pleasure of Augustus II the Strong, the Elec- tor of Saxony. -

Antique Pair Japanese Meiiji Imari Porcelain Vases C1880

anticSwiss 29/09/2021 17:25:52 http://www.anticswiss.com Antique Pair Japanese Meiiji Imari Porcelain Vases C1880 FOR SALE ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 19° secolo - 1800 Regent Antiques London Style: Altri stili +44 2088099605 447836294074 Height:61cm Width:26cm Depth:26cm Price:2250€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: A monumental pair of Japanese Meiji period Imari porcelain vases, dating from the late 19th Century. Each vase features a bulbous shape with the traditional scalloped rim, over the body decorated with reserve panels depicting court garden scenes and smaller shaped panels with views of Mount Fuji on chrysanthemums and peonies background adorned with phoenixes. Each signed to the base with a three-character mark and on the top of each large panel with a two-character mark. Instill a certain elegance to a special place in your home with these fabulous vases. Condition: In excellent condition, with no chips, cracks or damage, please see photos for confirmation. Dimensions in cm: Height 61 x Width 26 x Depth 26 Dimensions in inches: Height 24.0 x Width 10.2 x Depth 10.2 Imari ware Imari ware is a Western term for a brightly-coloured style of Arita ware Japanese export porcelain made in the area of Arita, in the former Hizen Province, northwestern Ky?sh?. They were exported to Europe in large quantities, especially between the second half of the 17th century and the first half of the 18th century. 1 / 4 anticSwiss 29/09/2021 17:25:52 http://www.anticswiss.com Typically Imari ware is decorated in underglaze blue, with red, gold, black for outlines, and sometimes other colours, added in overglaze.