China and Porcelain - Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phase Evolution of Ancient and Historical Ceramics

EMU Notes in Mineralogy, Vol. 20 (2019), Chapter 6, 233–281 The struggle between thermodynamics and kinetics: Phase evolution of ancient and historical ceramics 1 2 ROBERT B. HEIMANN and MARINO MAGGETTI 1Am Stadtpark 2A, D-02826 Go¨rlitz, Germany [email protected] 2University of Fribourg, Dept. of Geosciences, Earth Sciences, Chemin du Muse´e6, CH-1700 Fribourg, Switzerland [email protected] This contribution is dedicated to the memory of Professor Ursula Martius Franklin, a true pioneer of archaeometric research, who passed away at her home in Toronto on July 22, 2016, at the age of 94. Making ceramics by firing of clay is essentially a reversal of the natural weathering process of rocks. Millennia ago, potters invented simple pyrotechnologies to recombine the chemical compounds once separated by weathering in order to obtain what is more or less a rock-like product shaped and decorated according to need and preference. Whereas Nature reconsolidates clays by long-term diagenetic or metamorphic transformation processes, potters exploit a ‘short-cut’ of these processes that affects the state of equilibrium of the system being transformed thermally. This ‘short-cut’ is thought to be akin to the development of mineral-reaction textures resulting from disequilibria established during rapidly heated pyrometamorphic events (Grapes, 2006) involving contact aureoles or reactions with xenoliths. In contrast to most naturally consolidated clays, the solidified rock-like ceramic material inherits non-equilibrium and statistical states best described as ‘frozen-in’. The more or less high temperatures applied to clays during ceramic firing result in a distinct state of sintering that is dependent on the firing temperature, the duration of firing, the firing atmosphere, and the composition and grain-size distribution of the clay. -

'A Mind to Copy': Inspired by Meissen

‘A Mind to Copy’: Inspired by Meissen Anton Gabszewicz Independent Ceramic Historian, London Figure 1. Sir Charles Hanbury Williams by John Giles Eccardt. 1746 (National Portrait Gallery, London.) 20 he association between Nicholas Sprimont, part owner of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, Sir Everard Fawkener, private sec- retary to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the second son of King George II, and Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, diplomat and Tsometime British Envoy to the Saxon Court at Dresden was one that had far-reaching effects on the development and history of the ceramic industry in England. The well-known and oft cited letter of 9th June 1751 from Han- bury Williams (fig. 1) to his friend Henry Fox at Holland House, Kensington, where his china was stored, sets the scene. Fawkener had asked Hanbury Williams ‘…to send over models for different Pieces from hence, in order to furnish the Undertakers with good designs... But I thought it better and cheaper for the manufacturers to give them leave to take away any of my china from Holland House, and to copy what they like.’ Thus allowing Fawkener ‘… and anybody He brings with him, to see my China & to take away such pieces as they have a mind to Copy.’ The result of this exchange of correspondence and Hanbury Williams’ generous offer led to an almost instant influx of Meissen designs at Chelsea, a tremendous impetus to the nascent porcelain industry that was to influ- ence the course of events across the industry in England. Just in taking a ca- sual look through the products of most English porcelain factories during Figure 2. -

Grand Tour of European Porcelain

Grand Tour of European Porcelain Anna Calluori Holcombe explores the major European porcelain centres Left: Gilder. Bernardaud Factory. embarked on a modern version of the 17th and 18th century Grand Limoges, France. Tour of Europe in summer of 2010 and spent two months researching Right: Designer table setting display. porcelain (primarily tableware) from historical and technical per- Bernardaud Factory. Limoges, France. Photos by Anna Calluori Holcombe. Ispectives. The tradition of Grand Tour promoted the idea of travelling for the sake of curiosity and learning by travelling through foreign lands. On a research leave with a generous Faculty Enhancement Grant A factory was started in 1863 by some investors and, at about from the University of Florida (UF), I visited factories and museums in that time, an apprentice was hired 10 major European ceramics centres. named Léonard Bernardaud. He Prior to this interest in investigating European porcelain, I spent time worked his way up to become a studying Chinese porcelains with fascination and awe. On one of my partner, then acquiring the company in 1900 and giving it his name. many trips to China and my first visit to the famous city of Jingdezhen, I In 1949, the factory introduced climbed Gaoling Mountain, where the precious kaolin that is essential to the first gas-fuelled tunnel kiln in the Chinese porcelain formula was first mined more than 1000 years ago. France operated 24 hours a day, a Soft paste porcelain, which does not have the durability and translu- standard in most modern factories today. Although they had to cut 15 cency found in hard paste porcelain was in popular use in Europe prior percent of their employees in recent to their discovery of hard paste porcelain. -

A Detective Story: Meissen Porcelains Copying East Asian Models. Fakes Or Originals in Their Own Right?

A detective story: Meissen porcelains copying East Asian models. Fakes or originals in their own right? Julia Weber, Keeper of Ceramics at the Bavarian National Museum, Munich he ‘detective story’ I want to tell relates to how the French mer- fact that Saxon porcelain was the first in Europe to be seriously capable of chant Rodolphe Lemaire managed, around 1730, to have accurate competing with imported goods from China and Japan. Indeed, based on their copies of mostly Japanese porcelain made at Meissen and to sell high-quality bodies alone, he appreciated just how easily one might take them them as East Asian originals in Paris. I will then follow the trail of for East Asian originals. This realisation inspired Lemaire to embark on a new Tthe fakes and reveal what became of them in France. Finally, I will return business concept. As 1728 drew to a close, Lemaire travelled to Dresden. He briefly to Dresden to demonstrate that the immediate success of the Saxon bought Meissen porcelains in the local warehouse in the new market place copies on the Parisian art market not only changed how they were regarded and ordered more in the manufactory. In doing this he was much the same in France but also in Saxony itself. as other merchants but Lemaire also played a more ambitious game: in a bold Sometime around 1728, Lemaire, the son of a Parisian family of marchand letter he personally asked Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony and of faïencier, became acquainted with Meissen porcelain for the first time whilst Poland, to permit an exclusive agreement with the Meissen manufactory. -

Meissen Porcelain: Precision, Presentation, and Preservation

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 Meissen Porcelain: Precision, Presentation, and Preservation. How Artistic and Technological Significance Influence Conservation Protocol Nicole Peters West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Peters, Nicole, "Meissen Porcelain: Precision, Presentation, and Preservation. How Artistic and Technological Significance Influence Conservation Protocol" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 756. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/756 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Meissen Porcelain: Precision, Presentation, and Preservation. How Artistic and Technological Significance Influence Conservation Protocol. Nicole Peters Thesis submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Approved by Janet Snyder, Ph.D., Committee Chair Rhonda Reymond, Ph.D. Jeff Greenham, M.F.A. Michael Belman, M.S. Division of Art and Design Morgantown, West Virginia 2011 Keywords: Meissen porcelain, conservation, Fürstenzug Mural, ceramic riveting, material substitution, object replacement Copyright 2011 Nicole L. -

9. Ceramic Arts

Profile No.: 38 NIC Code: 23933 CEREMIC ARTS 1. INTRODUCTION: Ceramic art is art made from ceramic materials, including clay. It may take forms including art ware, tile, figurines, sculpture, and tableware. Ceramic art is one of the arts, particularly the visual arts. Of these, it is one of the plastic arts. While some ceramics are considered fine art, some are considered to be decorative, industrial or applied art objects. Ceramics may also be considered artifacts in archaeology. Ceramic art can be made by one person or by a group of people. In a pottery or ceramic factory, a group of people design, manufacture and decorate the art ware. Products from a pottery are sometimes referred to as "art pottery".[1] In a one-person pottery studio, ceramists or potters produce studio pottery. Most traditional ceramic products were made from clay (or clay mixed with other materials), shaped and subjected to heat, and tableware and decorative ceramics are generally still made this way. In modern ceramic engineering usage, ceramics is the art and science of making objects from inorganic, non-metallic materials by the action of heat. It excludes glass and mosaic made from glass tesserae. There is a long history of ceramic art in almost all developed cultures, and often ceramic objects are all the artistic evidence left from vanished cultures. Elements of ceramic art, upon which different degrees of emphasis have been placed at different times, are the shape of the object, its decoration by painting, carving and other methods, and the glazing found on most ceramics. 2. -

Meissen Masterpieces Exquisite and Rare Porcelain Models from the Royal House of Saxony to Be Offered at Christie’S London

For Immediate Release 30 October 2006 Contact: Christina Freyberg +44 20 7 752 3120 [email protected] Alexandra Kindermann +44 20 7 389 2289 [email protected] MEISSEN MASTERPIECES EXQUISITE AND RARE PORCELAIN MODELS FROM THE ROYAL HOUSE OF SAXONY TO BE OFFERED AT CHRISTIE’S LONDON British and Continental Ceramics Christie’s King Street Monday, 18 December 2006 London – A collection of four 18th century Meissen porcelain masterpieces are to be offered for sale in London on 18 December 2006 in the British and Continental Ceramics sale. This outstanding Meissen collection includes two white porcelain models of a lion and lioness (estimate: £3,000,000-5,000,000) and a white model of a fox and hen (estimate: £200,000-300,000) commissioned for the Japanese Palace in Dresden together with a white element vase in the form of a ewer (£10,000-15,000). “The porcelain menagerie was an ambitious and unparalleled project in the history of ceramics and the magnificent size of these models is a testament to the skill of the Meissen factory,” said Rodney Woolley, Director and Head of European Ceramics. “The sheer exuberance of these examples bears witness to the outstanding modelling of Kirchner and Kändler. The opportunity to acquire these Meissen masterpieces from the direct descendants of Augustus the Strong is unique and we are thrilled to have been entrusted with their sale,” he continued. The works of art have been recently restituted to the heirs of the Royal House of Saxony, the Wettin family. Commenting on the Meissen masterpieces, a spokesperson for the Royal House of Saxony said: “The Wettin family has worked closely, and over many years with the authorities to achieve a successful outcome of the restitution of many works of art among which are these four Meissen porcelain objects, commissioned by our forebear Augustus the Strong. -

Etch Imitation System for Porcelain and Bone China (One-Fire-Decal-Method)

Etch Imitation System for Porcelain and Bone China (One-Fire-Decal-Method) 1 General Information Etched decorations belong to the richest, most valuable precious metal designs to be found on tableware. However, etched decorations are not only work-intensive and expensive but they also require working with aggressive acids. Instead, producers work with etching imitation systems in which first a decal with a matt underlay and a bright relief on top is produced, applied onto the substrate to be decorated, and fired. Secondly, a liquid precious metal is applied by brush on top of the relief and the item is fired for a second time. With this Technical Information, Heraeus Ceramic Colours introduces a one-fire-etch imitation system for decals. The new decoration system consists of carefully adjusted components: special underlay, special medium, relief, precious metal paste. The perfect harmony of these components allows the production of an imitation etching in one decal, which only needs to be transferred and fired once! 2 Firing Conditions Substrate Firing Condition s Porcelain 800 - 820°C (1470-1508°F), 2 to 3 hours cold/cold Bone China 800 - 820°C (1470-1508°F), 2 to 3 hours cold/cold Worldwide there are many different glazes. The firing conditions differ from producer to producer. Pre-tests under own individual conditions are absolutely necessary. 3 Characteristics of the Products The product composition and the production process determine the major product characteristics of the components of the decoration system. Testing each production lot guarantees a constant product quality. With regard to the bright precious metal pastes of the system we regularly check the viscosity, the printing characteristics, the outline of printed test decorations as well as the precious metal colour shade and the brightness of the decoration after firing on a defined test substrate. -

Chromaphobia | Chromaphilia Presenting KCAI Alumni in the Ceramic Arts

Chromaphobia | Chromaphilia Presenting KCAI Alumni in the Ceramic Arts Kansas City Art Institute Gallery March 16 – June 3, 2016 Exhibition Checklist Chromaphobia Untitled Chromaphilia Lauren Mabry (’07 ceramics) 2015 Curved Plane Laura De Angelis (’95 sculpture) Silver plated brass and porcelain Cary Esser (‘78 ceramics) 2012 Hybrid Vigor 13 x 16 x 20 inches Chromaphilia Veils Red earthenware, slips, glaze 2012 Courtesy of the Artists 2015-2016 24 x 60 x 15 inches Ceramic, encaustic, fresh water pearls Glazed earthenware Dick and Gloria Anderson Collection, 20.5 x 16 x 9 inches Nathan Mabry (’01 ceramics) 16 x 79 x .75 inches Lake Quivira, Kansas Courtesy of Sherry Leedy Vanitas (Banana) Courtesy of Sherry Leedy Contemporary Art, Kansas City 2007 Contemporary Art, Kansas City and Fragmented Cylinder Cast rubber the Artist 2012 Teri Frame (’05 ceramics; art history) 8 x 8 x 8 inches red earthenware, slips, glaze Sons of Cain Lithophane #1 Courtesy of Cherry and Martin, Los Christian Holstad (’94 ceramics) 20 x 24 x 22 inches 2016 Angeles and the Artist Ouroboros 6 (Red with green and yellow snake) Dick and Gloria Anderson Collection, Bone china, walnut 2012 Lake Quivira, Kansas 9 x 7 x .25 inches Nobuhito Nishigawara Vintage glove, fiberfill and antique obi Courtesy of the Artist (’99 ceramics) 39 x 17 x 16 inches Pipe Form Untitled - Manual 3D Like Printer Courtesy of the Artist and Andrew 2014 Sons of Cain Lithophane #2 2013 Kreps Gallery, New York Red earthenware, slips and glaze 2016 Clay 20 x 28 x 28 inches Bone china, walnut 23 x -

Clay: Form, Function and Fantasy

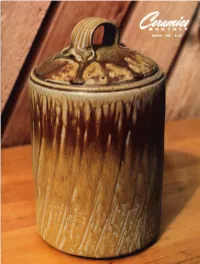

4 Ceramics Monthly Letters to the Editor................................................................................. 7 Answers to Questions............................................................................... 9 Where to Show.........................................................................................11 Suggestions ..............................................................................................15 Itinerary ...................................................................................................17 Comment by Don Pilcher....................................................................... 23 Delhi Blue Art Pottery by Carol Ridker...............................................31 The Adena-Hopewell Earthworks by Alan Fomorin..................36 A Gas Kiln for the Urban Potter by Bob Bixler..................................39 Clay: Form, Function and Fantasy.......................................................43 Computer Glazes for Stoneware by Harold J. McWhinnie ...................................................................46 The Three Kilns of Ken Ferguson by Clary Illian.............................. 47 Marietta Crafts National........................................................................ 52 Latex Tile Molds by Nancy Skreko Martin..........................................58 Three English Exhibitions...................................................................... 61 News & Retrospect...................................................................................73 -

Recommended Sights in and Around Dresden1

Porcelain circling the Globe. International Trading Structures and the East Asia Collection of Augustus the Strong (1670 – 1733) Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Wednesday, 13 – Thursday, 14 June 2018 Recommended sights in and around Dresden1 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden www.skd.museum [email protected] Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections) is one of the most renowned and oldest museum institutions in the world, originating from the collections of the Saxon electors in the 16th century. Today, the Dresden State Art Collections consists of fifteen museums. Most of them are located in the Residenzschloss (Royal Castle), the Zwinger and the Albertinum. Zwinger (Old Masters Painting Gallery, Porcelain Collection, Royal Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments) Sophienstraße, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 1 Residenzschloss (Green Vault, Collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, Coin Cabinet, Armory) Taschenberg 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Tuesdays Admission fee: regular €12.00, reduced €9.00, children under 17 free, group €11.00 Albertinum (New Masters Gallery, Sculpture Collection) Tzschirnerplatz 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 All information is supplied without guarantee. All obligation due to faulty, incomplete or outdated -

February 2018 Newsletter

San Francisco Ceramic Circle An Affiliate of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco February 2018 P.O. Box 26773, San Francisco, CA 94126 www.patricianantiques.com/sfcc.html SFCC FEBRUARY LECTURE A Glittering Occasion: Reflections on Dining in the 18th Century Sunday, FEBRUARY 25, 2017 9:45 a.m., doors open for social time Dr. Christopher Maxwell 10:30 a.m., program begins Curator of European Glass Gunn Theater, Legion of Honor Corning Museum of Glass About the lecture: One week later than usual, in conjunction with the Casanova exhibition at the Legion of Honor, the lecture will discuss the design and function of 18th-century tableware. It will address the shift of formal dining from daylight hours to artificially lit darkness. That change affected the design of table articles, and the relationship between ceramics and other media. About the speaker: Dr. Christopher L. Maxwell worked on the redevelopment of the ceramics and glass galleries at the Victoria and Albert Museum, with a special focus on 18th-century French porcelain. He also wrote the V&A’s handbook Eighteenth-Century French Porcelain (V&A Publications, 2010). From 2010 to 2016 he worked with 18th-century decorative arts at the Royal Collections. He has been Curator of European Glass at the Corning Museum of Glass since 2016. Dr. Maxwell is developing an exhibition proposal on the experience of light and reflectivity in 18th-century European social life. This month, our Facebook page will show 18th-century table settings and dinnerware. The dining room at Mount Vernon, restored to the 1785 color scheme of varnished dark green walls George Washington’s Mount Vernon, VA (photo: mountvernon.org SFCC Upcoming Lectures SUNDAY, MARCH 18, Gunn Theater: Gunn Theater: Jody Wilkie, Co-Chairman, Decorative Arts, and Director, Decorative Arts of the Americas, Christie’s: “Ceramics from the David Rockefeller collection.” SUNDAY, APRIL 15, Sally Kevill-Davies, cataloguer of the English porcelain at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, will speak on Chelsea porcelain figures.