Stephen R. Bown / Amundsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ice Shelf Advance and Retreat Rates Along the Coast of Queen Maud Land, Antarctica K

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 106, NO. C4, PAGES 7097–7106, APRIL 15, 2001 Ice shelf advance and retreat rates along the coast of Queen Maud Land, Antarctica K. T. Kim,1 K. C. Jezek,2 and H. G. Sohn3 Byrd Polar Research Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio Abstract. We mapped ice shelf margins along the Queen Maud Land coast, Antarctica, in a study of ice shelf margin variability over time. Our objective was to determine the behavior of ice shelves at similar latitudes but different longitudes relative to ice shelves that are dramatically retreating along the Antarctic Peninsula, possibly in response to changing global climate. We measured coastline positions from 1963 satellite reconnaissance photography and 1997 RADARSAT synthetic aperture radar image data for comparison with coastlines inferred by other researchers who used Landsat data from the mid-1970s. We show that these ice shelves lost ϳ6.8% of their total area between 1963 and 1997. Most of the areal reduction occurred between 1963 and the mid-1970s. Since then, ice margin positions have stabilized or even readvanced. We conclude that these ice shelves are in a near-equilibrium state with the coastal environment. 1. Introduction summer 0Њ isotherm [Tolstikov, 1966, p. 76; King and Turner, 1997, p. 141]. Following Mercer’s hypothesis, we might expect Ice shelves are vast slabs of glacier ice floating on the coastal these ice shelves to be relatively stable at the present time. ocean surrounding Antarctica. They are a continuation of the Following the approach of other investigators [Rott et al., ice sheet and form, in part, as glacier ice flowing from the 1996; Ferrigno et al., 1998; Skvarca et al., 1999], we compare the interior ice sheet spreads across the ocean surface and away position of ice shelf margins and grounding lines derived from from the coast. -

Arctic Marine Transport Workshop 28-30 September 2004

Arctic Marine Transport Workshop 28-30 September 2004 Institute of the North • U.S. Arctic Research Commission • International Arctic Science Committee Arctic Ocean Marine Routes This map is a general portrayal of the major Arctic marine routes shown from the perspective of Bering Strait looking northward. The official Northern Sea Route encompasses all routes across the Russian Arctic coastal seas from Kara Gate (at the southern tip of Novaya Zemlya) to Bering Strait. The Northwest Passage is the name given to the marine routes between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans along the northern coast of North America that span the straits and sounds of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Three historic polar voyages in the Central Arctic Ocean are indicated: the first surface shop voyage to the North Pole by the Soviet nuclear icebreaker Arktika in August 1977; the tourist voyage of the Soviet nuclear icebreaker Sovetsky Soyuz across the Arctic Ocean in August 1991; and, the historic scientific (Arctic) transect by the polar icebreakers Polar Sea (U.S.) and Louis S. St-Laurent (Canada) during July and August 1994. Shown is the ice edge for 16 September 2004 (near the minimum extent of Arctic sea ice for 2004) as determined by satellite passive microwave sensors. Noted are ice-free coastal seas along the entire Russian Arctic and a large, ice-free area that extends 300 nautical miles north of the Alaskan coast. The ice edge is also shown to have retreated to a position north of Svalbard. The front cover shows the summer minimum extent of Arctic sea ice on 16 September 2002. -

Supplementary File For: Blix A.S. 2016. on Roald Amundsen's Scientific Achievements. Polar Research 35. Correspondence: AAB Bu

Supplementary file for: Blix A.S. 2016. On Roald Amundsen’s scientific achievements. Polar Research 35. Correspondence: AAB Building, Institute of Arctic and Marine Biology, University of Tromsø, NO-9037 Tromsø, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] Selected publications from the Gjøa expedition not cited in the text Geelmuyden H. 1932. Astronomy. The scientific results of the Norwegian Arctic expedition in the Gjøa 1903-1906. Geofysiske Publikasjoner 6(2), 23-27. Graarud A. 1932. Meteorology. The scientific results of the Norwegian Arctic expedition in the Gjøa 1903-1906. Geofysiske Publikasjoner 6(3), 31-131. Graarud A. & Russeltvedt N. 1926. Die Erdmagnetischen Beobachtungen der Gjöa-Expedition 1903- 1906. (Geomagnetic observations of the Gjøa expedition, 1903-06.) The scientific results of the Norwegian Arctic expedition in the Gjøa 1903-1906. Geofysiske Publikasjoner 3(8), 3-14. Holtedahl O. 1912. On some Ordovician fossils from Boothia Felix and King William Land, collected during the Norwegian expedition of the Gjøa, Captain Amundsen, through the North- west Passage. Videnskapsselskapets Skrifter 1, Matematisk–Naturvidenskabelig Klasse 9. Kristiania (Oslo): Jacob Dybwad. Lind J. 1910. Fungi (Micromycetes) collected in Arctic North America (King William Land, King Point and Herschell Isl.) by the Gjöa expedition under Captain Roald Amundsen 1904-1906. Videnskabs-Selskabets Skrifter 1. Mathematisk–Naturvidenskabelig Klasse 9. Christiania (Oslo): Jacob Dybwad. Lynge B. 1921. Lichens from the Gjøa expedition. Videnskabs-Selskabets Skrifter 1. Mathematisk– Naturvidenskabelig Klasse 15. Christiania (Oslo): Jacob Dybwad. Ostenfeld C.H. 1910. Vascular plants collected in Arctic North America (King William Land, King Point and Herschell Isl.) by the Gjöa expedition under Captain Roald Amundsen 1904-1906. -

Sir John Franklin and the Arctic

SIR JOHN FRANKLIN AND THE ARCTIC REGIONS: SHOWING THE PROGRESS OF BRITISH ENTERPRISE FOR THE DISCOVERY OF THE NORTH WEST PASSAGE DURING THE NINE~EENTH CENTURY: WITH MORE DETAILED NOTICES OF THE RECENT EXPEDITIONS IN SEARCH OF THE MISSING VESSELS UNDER CAPT. SIR JOHN FRANKLIN WINTER QUARTERS IN THE A.ROTIO REGIONS. SIR JOHN FRANKLIN AND THE ARCTIC REGIONS: SHOWING FOR THE DISCOVERY OF THE NORTH-WEST PASSAGE DURING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: WITH MORE DETAILED NOTICES OF THE RECENT EXPEDITIONS IN SEARCH OF THE MISSING VESSELS UNDER CAPT. SIR JOHN FRANKLIN. BY P. L. SIMMONDS, HONORARY AND CORRESPONDING JIIEl\lBER OF THE LITERARY AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF QUEBEC, NEW YORK, LOUISIANA, ETC, AND MANY YEARS EDITOR OF THE COLONIAL MAGAZINE, ETC, ETC, " :Miserable they Who here entangled in the gathering ice, Take their last look of the descending sun While full of death and fierce with tenfold frost, The long long night, incumbent o•er their heads, Falls horrible." Cowl'ER, LONDON: GEORGE ROUTLEDGE & CO., SOHO SQUARE. MDCCCLI. TO CAPT. SIR W. E. PARRY, R.N., LL.D., F.R.S., &c. CAPT. SIR JAMES C. ROSS, R.N., D.C.L., F.R.S. CAPT. SIR GEORGE BACK, R.N., F.R.S. DR. SIR J. RICHARDSON, R.N., C.B., F.R.S. AND THE OTHER BRAVE ARCTIC NAVIGATORS AND TRAVELLERS WHOSE ARDUOUS EXPLORING SERVICES ARE HEREIN RECORDED, T H I S V O L U M E I S, IN ADMIRATION OF THEIR GALLANTRY, HF.ROIC ENDURANCE, A.ND PERSEVERANCE OVER OBSTACLES OF NO ORDINARY CHARACTER, RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED, BY THEIR VERY OBEDIENT HUMBLE SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. -

Transits of the Northwest Passage to End of the 2020 Navigation Season Atlantic Ocean ↔ Arctic Ocean ↔ Pacific Ocean

TRANSITS OF THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE TO END OF THE 2020 NAVIGATION SEASON ATLANTIC OCEAN ↔ ARCTIC OCEAN ↔ PACIFIC OCEAN R. K. Headland and colleagues 7 April 2021 Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge, United Kingdom, CB2 1ER. <[email protected]> The earliest traverse of the Northwest Passage was completed in 1853 starting in the Pacific Ocean to reach the Atlantic Oceam, but used sledges over the sea ice of the central part of Parry Channel. Subsequently the following 319 complete maritime transits of the Northwest Passage have been made to the end of the 2020 navigation season, before winter began and the passage froze. These transits proceed to or from the Atlantic Ocean (Labrador Sea) in or out of the eastern approaches to the Canadian Arctic archipelago (Lancaster Sound or Foxe Basin) then the western approaches (McClure Strait or Amundsen Gulf), across the Beaufort Sea and Chukchi Sea of the Arctic Ocean, through the Bering Strait, from or to the Bering Sea of the Pacific Ocean. The Arctic Circle is crossed near the beginning and the end of all transits except those to or from the central or northern coast of west Greenland. The routes and directions are indicated. Details of submarine transits are not included because only two have been reported (1960 USS Sea Dragon, Capt. George Peabody Steele, westbound on route 1 and 1962 USS Skate, Capt. Joseph Lawrence Skoog, eastbound on route 1). Seven routes have been used for transits of the Northwest Passage with some minor variations (for example through Pond Inlet and Navy Board Inlet) and two composite courses in summers when ice was minimal (marked ‘cp’). -

AQUILA BOOKS Specializing in Books and Ephemera Related to All Aspects of the Polar Regions

AQUILA BOOKS Specializing in Books and Ephemera Related to all Aspects of the Polar Regions Winter 2012 Presentation copy to Lord Northcliffe of The Limited Edition CATALOGUE 112 88 ‘The Heart of the Antarctic’ 12 26 44 49 42 43 Items on Front Cover 3 4 13 9 17 9 54 6 12 74 84 XX 72 70 21 24 8 7 7 25 29 48 48 48 37 63 59 76 49 50 81 7945 64 74 58 82 41 54 77 43 80 96 84 90 100 2 6 98 81 82 59 103 85 89 104 58 AQUILA BOOKS Box 75035, Cambrian Postal Outlet Calgary, AB T2K 6J8 Canada Cameron Treleaven, Proprietor A.B.A.C. / I.L.A.B., P.B.F.A., N.A.A.B., F.R.G.S. Hours: 10:30 – 5:30 MDT Monday-Saturday Dear Customers; Welcome to our first catalogue of 2012, the first catalogue in the last two years! We are hopefully on schedule to produce three catalogues this year with the next one mid May before the London Fairs and the last just before Christmas. We are building our e-mail list and hopefully we will be e-mailing the catalogues as well as by regular mail starting in 2013. If you wish to receive the catalogues by e-mail please make sure we have your correct e-mail address. Best regards, Cameron Phone: (403) 282-5832 Fax: (403) 289-0814 Email: [email protected] All Prices net in US Dollars. Accepted payment methods: by Credit Card (Visa or Master Card) and also by Cheque or Money Order, payable on a North American bank. -

Who Discovered the Northwest Passage? Janice Cavell1

ARCTIC VOL. 71, NO.3 (SEPTEMBER 2018) P.292 – 308 https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4733 Who Discovered the Northwest Passage? Janice Cavell1 (Received 31 January 2018; accepted in revised form 1 May 2018) ABSTRACT. In 1855 a parliamentary committee concluded that Robert McClure deserved to be rewarded as the discoverer of a Northwest Passage. Since then, various writers have put forward rival claims on behalf of Sir John Franklin, John Rae, and Roald Amundsen. This article examines the process of 19th-century European exploration in the Arctic Archipelago, the definition of discovering a passage that prevailed at the time, and the arguments for and against the various contenders. It concludes that while no one explorer was “the” discoverer, McClure’s achievement deserves reconsideration. Key words: Northwest Passage; John Franklin; Robert McClure; John Rae; Roald Amundsen RÉSUMÉ. En 1855, un comité parlementaire a conclu que Robert McClure méritait de recevoir le titre de découvreur d’un passage du Nord-Ouest. Depuis lors, diverses personnes ont avancé des prétentions rivales à l’endroit de Sir John Franklin, de John Rae et de Roald Amundsen. Cet article se penche sur l’exploration européenne de l’archipel Arctique au XIXe siècle, sur la définition de la découverte d’un passage en vigueur à l’époque, de même que sur les arguments pour et contre les divers prétendants au titre. Nous concluons en affirmant que même si aucun des explorateurs n’a été « le » découvreur, les réalisations de Robert McClure méritent d’être considérées de nouveau. Mots clés : passage du Nord-Ouest; John Franklin; Robert McClure; John Rae; Roald Amundsen Traduit pour la revue Arctic par Nicole Giguère. -

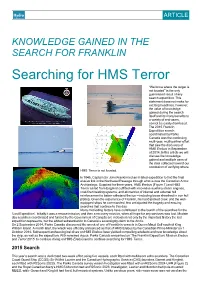

Searching for HMS Terror

ARTICLE KNOWLEDGE GAINED IN THE SEARCH FOR FRANKLIN Searching for HMS Terror “We know where the target is not located” is the only guaranteed result of any search expedition. This statement does not make for exciting headlines, however, the value of knowledge gained during the search itself and its many benefits to a variety of end-users, cannot be easily dismissed. The 2015 Franklin Expedition search coordinated by Parks Canada was the continuing multi-year, multi-partner effort that saw the discovery of HMS Erebus in September of 2014. In this article we will discuss the knowledge gained and multiple uses of the data collected toward our conclusion of verifying where HMS Terror is not located. In 1845, Captain Sir John Franklin led an ill-fated expedition to find the final elusive link in the Northwest Passage through what is now the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Supplied for three years, HMS Erebus (Figure 1) and HMS Terror sailed from England outfitted with innovative auxiliary steam engines, coal-fired heating systems, and all manner of internal and external hull reinforcement to better withstand the ice -- including bows sheathed in iron hull plating. Given the experience of Franklin, his hand-picked crew, and the well- equipped ships he commanded, few anticipated the tragedy and ensuing searches that continue to this day. Many motivating factors have contributed to the launch of the searches for the ‘Lost Expedition’. Initially it was a rescue mission, and then a recovery mission, when all hope for any survivors was lost. Modern day searches coordinated and funded by the Government of Canada are motivated not only by the important history the lost expedition represents, but the added substantiation to Canada’s sovereignty claim to the Arctic. -

Sail from Dover DAY 9 | Romsdalsmuseet, One of Finnsnes / Senja Norway’S Largest Folk Museums

Return address Hurtigruten Ltd, Unit 1a, Commonwealth Buildings, Woolwich Church Street, SE18 5NS <T><F><S> <COMPANY> <ADDR1> <ADDR2> <ADDR3> <ADDR4> <ADDR5> <ADDR6> <ADDR7> Cust. ref.:<ACCOUNT_ID> <TOWN> <COUNTY> <Job ref>/<Cell>/<Seq. No> <ZIP> <SSC>/<Bag ID>/<Bag no.>/<MS brake> Notifi cation: We use your information in accordance with our Privacy Policy, updated June 2019. Please see www.hurtigruten.co.uk/practical-information/statement-of-privacy/ New expedition cruises 2021 | 2022 SAIL from save up to 20%* DOVER British Isles | Norway’s Northern Lights | Norway’s Arctic sunshine & Fjords | southern Scandinavia MS MAUD welcome For 127 years, Hurtigruten have been With our unique Science Center pioneers in expedition cruising, from as the beating heart of the ship, the rugged coastline of Norway and our expedition team serve as hosts, the Arctic islands, to the remote lecturers, instructors, companions continent of Antarctica. Our mission and guides as they bring to life is to deliver authentic adventures for breath-taking destinations. the naturally curious. Your health and safety is our I am thrilled to present our series top priority, and we constantly of NEW expedition cruises update our protocols and safety from Dover for 2021/22. Start guidelines, in consultation with your holiday without the stress of the Norwegian Government and a crowded airport, as we embark with local health authorities. from the beautiful cruise terminal Please book with confidence, in Dover, to discover hand-picked and for the latest information, gems on expertly-planned itineraries visit our website. visiting the British Isles, southern We can’t wait to welcome you Scandinavia and the stunning onboard MS Maud. -

Inventory Acc.12696 William Laird Mckinlay

Acc.12696 December 2006 Inventory Acc.12696 William Laird McKinlay National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Correspondence and papers of William Laird McKinlay, Glasgow. Background William McKinlay (1888-1983) was for most of his working life a teacher and headmaster in the west of Scotland; however the bulk of the papers in this collection relate to the Canadian National Arctic Expedition, 1913-18, and the part played in it by him and the expedition leader, Vilhjalmur Stefansson. McKinlay’s account of his experiences, especially those of being shipwrecked and marooned on Wrangel Island, off the coast of Siberia, were published by him in Karluk (London, 1976). For a rather more detailed list of nos.1-27, and nos.43-67 (listed as nos.28-52), see NRA(S) survey no.2546. Further items relating to McKinlay were presented in 2006: see Acc.12713. Other items, including a manuscript account of the expedition and the later activities of Stefansson – much broader in scope than Karluk – have been deposited in the National Archives of Canada, in Ottawa. A small quantity of additional documents relating to these matters can be found in NRA(S) survey no.2222, papers in the possession of Dr P D Anderson. Extent: 1.56 metres Deposited in 1983 by Mrs A.A. Baillie-Scott, the daughter of William McKinlay, and placed as Dep.357; presented by the executor of Mrs Baillie-Scott’s estate, November 2006. -

Historical Profile of the Great Slave Lake Area's Mixed European-Indian Ancestry Community

Historical Profile of the Great Slave Lake Area’s Mixed European-Indian Ancestry Community by Gwynneth Jones Research and & Aboriginal Law and Statistics Division Strategic Policy Group The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Justice Canada. i Table of Contents Abstract ii Author’s Biography iii I. Executive Summary iv II. Methodology/Introduction vi III. Narrative A. First Contact at Great Slave Lake, 1715 - 1800 1 B. Mixed-Ancestry Families in the Great Slave Lake Region to 1800 12 C. Fur Trade Post Life at 1800 19 D. Development of the Fur Trade and the First Mixed-Ancestry Generation, 1800 - 1820 25 E. Merger of the Fur Trade Companies and Changes in the Great Slave Lake Population, 1820 - 1830 37 F. Fur Trade Monopoly and the Arrival of the Missionaries, 1830 - 1890 62 G. Treaty, Traders and Gold, 1890 - 1900 88 H. Increased Presence and Regulations by Persons not of Indian/ Inuit/Mixed-Ancestry Descent, 1905 - 1950 102 IV. Discussion/Summary 119 V. Suggestions for Future Research 129 VI. References VII. Appendices Appendix A: Extracts of Selected Entries in Oblate Birth, Marriage and Death Registers Appendix B: Métis Scrip -- ArchiviaNet (Summaries of Genealogical Information on Métis Scrip Applications) VIII. Key Documents and Document Index (bound separately) Abstract With the Supreme Court of Canada decision in R. v. Powley [2003] 2 S.C.R., Métis were recognized as having an Aboriginal right to hunt for food as recognized under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. -

(TSFN): 0402917N-M AMENDED Research Report 2017 Gjoa Haven

Toward a Sustainable Fishery for Nunavummiut (TSFN): 0402917N-M AMENDED Research Report 2017 Gjoa Haven HTA and Queen’s University (Supervisor: Virginia K. Walker; M. Sc. Students: Erin Hamilton and Geraint Element; Queen’s University, Department of Biology, Kingston, ON, K7L 3N6) Assessment of Water Microbial Communities and Microplastics in the Canadian Arctic’s Lower Northwest Passage (Kitikmeot Region) Section 1: Collection of Surface Water for Fish Microbiome Study Background Information Both fish slime on the scales as well as the intestines is made up of cells associated with the fish immune system as well as the microbiota or beneficial microorganisms. The microorganisms including symbiotic bacteria contribute to the health of the fish and by extension, the health of fish stocks. It is thought that the microbiomes contribute to fish well-being either through competing with harmful bacteria and therefore excluding them, or through a more complex interaction with the host immune defense response. From an academic view, it is important to characterize the microbiomes of fish to infer the functions these microbes serve to increase understanding of fish immunity, but from a practical view, knowledge of the fish microbiomes and of the waters they live in, will provide insight into the impact of climate change on fish populations that are an important food source to communities in the Northwest Passage. Accompanied by community members from Gjoa Haven, a research team sampled fish and water from fresh and saltwater sites around King William Island, Nunavut (with separate fish sampling permits and animal care permits for this aspect of the work; see application material).