Report Into Infant Cremations at the Emstrey Crematorium Shrewsbury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

About the Cycle Rides

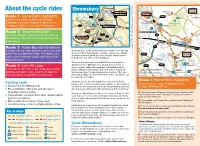

Sundorne Harlescott Route 45 Rodington About the cycle rides Shrewsbury Sundorne Mercian Way Heath Haughmond to Whitchurch START Route 1 Abbey START Route 2 START Route 1 Home Farm Highlights B5067 A49 B5067 Castlefields Somerwood Rodington Route 81 Gentle route following Route 81 through Monkmoor Uffington and Upton Magna to Home Farm, A518 Pimley Manor Haughmond B4386 Hill River Attingham. Option to extend to Rodington. Town Centre START Route 3 Uffington Roden Kingsland Withington Route 2 Around Attingham Route 44 SHREWSBURY This ride combines some places of interest in Route 32 A49 START Route 4 Sutton A458 Route 81 Shrewsbury with visits to Attingham Park and B4380 Meole Brace to Wellington A49 Home Farm. A5 Upton Magna A5 River Tern Walcot Route 3 Acton Burnell Adventure © Crown copyright and database rights 2012 Ordnance Survey 100049049 A5 A longer ride for more experienced cyclists with Shrewsbury is a very attractive historic market town nestled in a loop of the River Severn. The town centre has a largely Berwick Route 45 great views of Wenlock Edge, The Wrekin and A5064 Mercian Way You are not permitted to copy, sub-licence, distribute or sell any of this data third parties in form unaltered medieval street plan and features several timber River Severn Wharf to Coalport B4394 visits to Acton Burnell Castle and Venus Pool framed 15th and 16th century buildings. Emstrey Nature Reserve Home Farm The town was founded around 800AD and has played a B4380 significant role in British history, having been the site of A458 Attingham Park Uckington Route 4 Lyth Hill Loop many conflicts, particularly between the English and the A rewarding ride, with a few challenging climbs Welsh. -

Emstrey House South Shrewsbury Business Park, SY2

Emstrey House South Shrewsbury Business Park, SY2 6LG To Let Ground floor offices Modern offices approximately 130.64 sq m / 1,398 sq ft 6 car parking spaces Established and expanding business park location Excellent road communications to the A5, A49 and the M54 beyond EPC – D93 £17,500 per annum 01743 276 230 Chartered Surveyors ● Estate Agents www.barbers-online.co.uk Ground Floor Services Emstrey House South Mains water, electricity, drainage and gas are connected to Shrewsbury Business Park the property. The property has gas fired central heating and Shrewsbury the heating supply is charged as a service charge by the SY2 6LG landlord. Location VAT The offices comprise the ground floor of Emstrey House at All figures quoted are exclusive of VAT which may be Shrewsbury Business Park which is an established office payable under the prevailing rate. location approximately 3 miles from Shrewsbury Town Centre. The Business Park is located close to the A5 and Legal Costs A49 dual carriageway which gives good access to Telford Each party is to be responsible for their own legal costs in and the national motorway network. connection with this matter. Description Viewing The property comprises a ground floor self-contained office Strictly by prior appointment with the sole agent, Barbers: suite with six car parking spaces. Tel: 01743 276 Email: [email protected] Accommodation 1 Church Street The property comprises the following accommodation Wellington (all measurements are approximate): Telford Shropshire Offices overall 130.64 sq m 1398 sq ft TF1 1DD The accommodation comprises a reception office, meeting Anti-Money Laundering room, two private offices and a general office. -

Offers in the Region of £349,995 Through the Agent 2

Poppy Cottage, Emstrey, Atcham, Shrewsbury, SY5 6QP www.hbshrop.co.uk Important Notice - please read carefully All rents, premiums or other financial arrangements and charges stated are exclusive of value added tax. The Property Misdescriptions Act Holland Broadbridge for themselves and for the vendors or lessors of this property whose agents they are give notice that: Viewing: strictly by appointment 1. These particulars are set out as a general outline only for the guidance of intended purchasers or lessors and do not constitute part of an offer or contract. Offers in the region of £349,995 through the agent 2. All descriptions, dimensions, reference to condition and necessary permissions for use and occupation, and other details are given without responsibility and any intending purchasers or tenants should not rely on them as statements or representations of fact but must satisfy themselves by inspection or otherwise as to the correctness of each term of them. 3. The vendors or lessors do not make or give, and neither do Holland Broadbridge for themselves nor any person in their employment has any authority to make or give any representation or warranty whatever in relation to this property. Holland Broadbridge t: 01743 357 000 Agriculture House, 5 Barker Street, Shrewsbury, Shropshire SY1 1QJ e: [email protected] Agriculture House, 5 Barker Street, Shrewsbury, Shropshire SY1 1QJ www.hbshrop.co.uk Poppy Cottage, Emstrey, Atcham, Shrewsbury, SY5 6QP Believed to date back to approximately 1850 this former stables now offers exceptionally well presented and charming living accommodation throughout, having an attractive lounge, delightful kitchen / breakfast room, two bedrooms plus an additional detached self contained annexe which currently produces a monthly rental income of £350 per calendar month. -

An Archaeological Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Shropshire A.D. 600 – 1066: with a Catalogue of Artefacts

An Archaeological Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Shropshire A.D. 600 – 1066: With a catalogue of artefacts By Esme Nadine Hookway A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MRes Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Anglo-Saxon period spanned over 600 years, beginning in the fifth century with migrations into the Roman province of Britannia by peoples’ from the Continent, witnessing the arrival of Scandinavian raiders and settlers from the ninth century and ending with the Norman Conquest of a unified England in 1066. This was a period of immense cultural, political, economic and religious change. The archaeological evidence for this period is however sparse in comparison with the preceding Roman period and the following medieval period. This is particularly apparent in regions of western England, and our understanding of Shropshire, a county with a notable lack of Anglo-Saxon archaeological or historical evidence, remains obscure. This research aims to enhance our understanding of the Anglo-Saxon period in Shropshire by combining multiple sources of evidence, including the growing body of artefacts recorded by the Portable Antiquity Scheme, to produce an over-view of Shropshire during the Anglo-Saxon period. -

The London Gazette, 16Th September 1988

10390 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 16TH SEPTEMBER 1988 north west of Montford Bridge to the MS4 at Cluddley and from of any objection or representation may be communicated to other Preston to Battlefield in the County of Shropshire, he proposes to people who may be affected by it. make an Order under section 10 of Highways Act 1980 which will G. F. Robertson, A Principal in the Department of Transport, vary the (AS) London-Holyhead Trunk Road and Slip Roads and West Midlands Regional Office, Birmingham. (Ref. the (A49 ) Newport-Shrewsbury-Whitchurch-Warrington Trunk T1398/28R/0660.) Road (AS/A49 Shrewsbury By-pass and Improvements) Order 1985 by changing slightly the route of the by-pass for a short section in the 10th August 1988. (12 SI) vicinity of Button Hall. Copies of the draft Order and of the relevant plan together with the made Line Orders may be inspected for 16th September 1988 HIGHWAYS ACT 1980 until 28th October 1988 or within 6 weeks from the date of The A5/A49 Trunk Roads (Shrewsbury By-pass and Improvements) publication of this notice, whichever period shall expire later, at the (Temporary Bridge over the River Severn at Uffington, Department of Transport at 2 Marsham Street, London S.W.I, and Shrewsbury) Order 198 . at the offices of the Director (Transport), West Midlands Regional Office, Department of Transport, No 5 Broadway, Broad Street, The Secretary of State for Transport proposes to make an Order Birmingham B151BL, and at Shropshire County Council, Shirehall, under section 106 of the Highways Act 1980 which will authorise him Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury; Shrewsbury, and Atcham Borough to construct a temporary bridge for the purposes of transporting Council, Guildhall, Dogpole, Shrewsbury; The Wrekin District spoil, building materials and machinery in connection with the new Council, Malinslee House, Dawley, Telford, and at the Sub Post trunk road and River Severn crossing at Uffington, Shrewsbury. -

Cardington Eaton-Under- Heywood Hope Bowdler Rushbury

Welcome to the Revd. Sam Mann and his wife Aisha! Cardington Eaton-under- Heywood Hope Bowdler Rushbury October 2020 50p News and views from around the four parishes and their villages Contacts: Copy to [email protected] Finance and distribution to 1 [email protected] Advertising enquiries to [email protected] The Honeypot - MAGazine for the Apedale Parishes Cardington, Eaton-under-Heywood, Hope Bowdler, Rushbury EDITORIAL TEAM: Editor Andrea Millard Occasional editors Peter Thorpe, VACANCY ALL COPY FOR THE MAGAZINE SHOULD BE SENT DIRECT TO THE EDITORIAL TEAM BY E-MAIL AT THE FOLLOWING ADDRESS: [email protected] (DO NOT SEND COPY OR ROTAS DIRECT TO ANDREA.) GENERAL ENQUIRIES TO: Editor: Andrea Millard Tel. 01694 771675 Contributions: for the following month to reach the Editorial Team by the date given on page 2. WE ARE AWARE THAT THERE WILL BE SOME PEOPLE WHO DO NOT HAVE ACCESS TO E-MAIL. THESE PEOPLE SHOULD PASS ON THEIR COPY IN GOOD TIME TO ONE OF THE DESIGNATED CONTACTS (DETAILS BELOW) WHO WILL PASS IT ON TO THE EDITORIAL TEAM. Ruth Jenkins The Manor, Hope Bowdler,SY6 7DD 01694 724919 [email protected] Diana Hamlin 2 Mount View, Hope Bowdler, SY6 7DQ.Tel. 01694 658036 Darren Merrill Church House, Rushbury. SY6 7EB Tel. 01694 771341 Sue Akers Maltster’s Tap, Cardington. Tel. 01694 771530 DATES AHEAD FOR THE COMING YEAR FOR INCLUSION IN FOUR PARISHES EVENTS CALENDAR: Notify dates as early as possible to the respective *Secretary to P.C.C., listed with the church contacts later in the magazine. Subscription and Distribution Enquiries within each Parish to: Cardington: Mrs Jane McMillan 01694 771424 Eaton: Mrs Jenny Rose 01584 841251 Hope Bowdler: Mr Mervyn Lewis 01694 722413 [email protected] Rushbury: Mrs Margaret Barre 01694 771215 ADVERTISEMENTS: Box advertisements and advertising enquiries to: Donna Dixon Tel. -

Shropshire. (Kelly's

~36 fAR SHROPSHIRE. (KELLY'S FARMERS""""-'-ntinued. Farmel' Edwd. Bridgwalton~ Bridgnorth 'Franks Joseph, Sutton, Shrewsbury Evans John,Rorrington,ChirburyR.S.O Farmer George, Walton, Bewdley Franks Wm.Emstrey,Atchm.Shrwsbnry Evans John, The Lodge, Broncroft, FarmerJohnEdwd.EastHamlet,Ludlow Freeman John, Berghill, Oswestry Craven Arms R.S.O Farmer John Edward, Felton, Ludlow Freeman Joseph Edward, Diddlebury~ Evans John, Wi:xhill,.Weston-with-Wix- Farmer Mrs. Mary, Stanton Lacy, Craven Anns R.S.O hill, Shrewsbury Bromfield R.S.O Froggatt Thomas, jun. Ashford farm, Evans J oseph, Church Preen, Shrwsbry Farmer N. Tugford, Craven Arms R. S. 0 Ash ford Carbonell, Ludlow Evans J. Grimmer,Minsterley, Shrwsby FarmerT.Thonglnds.MuchMenlck.R.S.O Froggat.t Thomas, Feather knowl, Ash. Evans Joseph, Hogstow, Grimmer,Min- Farmer Thos. Winsbury, Chirbury R.S.O ford Rowdie-r, Ludlow sterley, Shrewsbury Farmer William, 'rhe Hall, Rorrington, FryerJn.Broads'lane, Tuck hill,Bridgnrth Evans Jsph.Rea side,CleoburyMortimer Chirbury R.S.O Furber John, Ightfield, Whitchurch Evans L. Cockshutt,Cound,Shrewsbury Farr William & James, Netchwood, Furber Joseph, Styche & Woodlands, Evans Mrs M. Forest, Selattyn,Oswestry Middleton Priors, Bridgnorth Market Drayton Evans MrsM.Lawnt,Cynynion,Oswestry Farr James, Wheathill, Bridgnorth Furber Thos. Bletchley, Market Drayton Evans Mrs.MaryA.Aston-on-ClunR.S. 0 Farr S.HoltPreen,Leebotwood,Shrwsbry Furnival F.W. Bearstone, MarketDrayton Evans Morris, Graigwenfawr, Sychtyn, Farr William, Cleobury Mortimer Furnival M. Sutton, Market Drayton Oswestry FarrierJ.Neachhill,Doningtn.W'hamptn Gaiter Joseph, Stanton, Shrewsbury EvansR. Barnslands fm. Cleobry. Mortmr Farrington.R. W estonL ullingfld.Shrwsby Galbraith P. Chetwynd Aston, N ewpOt."t. EvansR.Bostock's hall, Whixll. -

Blue Bell Wood, Blue Bell, Uppington, Telford, TF6 5HG Blue Bell Wood, Blue Bell, Uppington, Telford, TF6 5HG

Blue Bell Wood, Blue Bell, Uppington, Telford, TF6 5HG Blue Bell Wood, Blue Bell, Uppington, Telford, TF6 5HG Amenity woodland with potential for alternative uses. Extending to approximately 0.723 of an acre. Situated between Wellington and Shrewsbury. Wellington - 3.2 miles, Shrewsbury - 6 miles, Telford - 5.8 miles, Birmingham - 30 miles. (All distances are approximate). The sale offers the rare opportunity to purchase an attractive block of amenity woodland with potential for alternative uses, located in this rural Shropshire location and within easy reach of Telford and Shrewsbury and excellent transport links. The site offers the opportunity, subject to necessary planning consents, for alternative uses. DESCRIPTION A small block of amenity woodland and garden land comprising a mix of tree species. The land was last used as amenity garden land and contains several dilapidated wooden garage buildings and storage sheds. The land enjoys a lengthy road frontage against the Old A5 (B5061) which could be used for access, or alternatively, a dedicated access is included in the sale to the north, that leads directly onto a minor country lane. To the north, the land is bordered by two residential properties, with the M54/A5 beyond. To the east, a further residential property with the old A5 running along the entire southern boundary. To the west is open agricultural land with views towards the Shropshire hills and beyond. NB: Formal planning advice has not been sought from Shropshire Council and this land is being sold as amenity woodland. Prospective purchasers are to make their own independent planning enquiries. There is a Clawback provision of 20% on uplift in value for anything other than one single dwelling within 20 years of sale. -

A Minimum of 100 Signed Pieces of Memorabilia from Stars of Both the Past and the Present…

How to get to ‘The Wroxeter Hotel’, Wroxeter… Working in conjunction with ‘F.A.C.E.’ (“For Autograph Collectors Everywhere”) Martin Richardson proudly presents… A charity auction in aid of “The Severn Hospice” & “Hope House” Sunday November the 25th, 2012… 2 o’clock pm start at ‘The Wroxeter Hotel’, Wroxeter, Shropshire. *********************************** The Wroxeter Hotel, Wroxeter, Nr Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY5 6PH. (01743) 761256. A minimum of 100 From the M54 Telford… Leave the M54 at junction 7. signed pieces of Turn right off the slip road onto the Holyhead road. Proceed under the motorway bridge and turn immediately left onto the B5061. Continue for 4.4 miles and then turn left onto the B4394 following signs for memorabilia from ‘Wroxeter Roman City & Vineyard’. Continue half a mile to the cross roads. Proceed straight across passing the ruins on your left. stars of both the past The hotel is on the left, before the church just 500 yards past the ruins. From The A5 Shrewsbury Ring Road… and the present… Turn off ring road at Emstrey Roundabout onto B4380 (Ironbridge signed). Continue straight ahead on the B4380 for 2.8 miles. (...And in the best tradition of ‘F.A.C.E.’ Just after Atcham Bridge (past Attingham Park seen on your left) the road forks and the B4380 turns off to the right.. signed memorabilia auctions there will Take this right signposted Ironbridge and Wroxeter. After half a mile turn right at the cross roads passing the ruins on your left. also be one or two extra surprises as well!) The hotel is on the left, before the church just 500 yards past the ruins. -

Lower Super Output Area (LSOA) Name LSOA Location Population

Lower Super Crimes Crimes Population Output Area LSOA location July 15 to per 1,000 2015 (LSOA) name June 2018 per year Shropshire 019A Shrewsbury loop 2,186 2897 442 Shropshire 007A Oswestry centre 1,223 1607 438 Shropshire 038H Ludlow Old St Corve St Galdeford 1,041 543 174 Shropshire 005A Market Drayton north 1,992 889 149 Shropshire 015D Shrewsbury Harlescott Grange 1,608 707 147 Shropshire 033A Bridgnorth Low Town 1,650 688 139 Shropshire 015A Shrewsbury Ditherington 1,582 557 117 Shropshire 015B Shrewsbury Ditherington 1,667 571 114 Shropshire 001D Whitchurch south west 1,728 591 114 Shropshire 023D Shrewsbury Meole Brace Church Ln 1,678 548 109 Shropshire 038B Ludlow Sandpits 1,112 344 103 Shropshire 001A Whitchurch centre 1,723 508 98 Shropshire 022C Shrewsbury Sutton 1,379 399 96 Shropshire 036D Craven Arms central 1,165 321 92 Shropshire 016C Shrewsbury Sundorne 1,620 436 90 Shropshire 033B Bridgnorth High Town 1,491 399 89 Shropshire 017D Shrewsbury Castle Fields 2,063 547 88 Shropshire 034D Kemberton Beckbury 1,451 378 87 Shropshire 016A Shrewsbury Harlescott Battlefield 2,335 596 85 Shropshire 016D Shrewsbury Featherbed Lane 2,072 517 83 Shropshire 008A Wem east of centre 1,804 436 81 Shropshire 023C Shrewsbury Meole Brace Moneybrook 1,610 389 81 Shropshire 015E Shrewsbury Knights Way 1,799 432 80 Shropshire 006E Oswestry south east 1,634 377 77 Shropshire 005B Market Drayton east 1,336 305 76 Shropshire 038I Ludlow Town centre Bromfield Rd 1,233 279 75 Shropshire 003C Gobowen centre 1,277 287 75 Shropshire 025D Shifnal centre -

Learning the Landscape Through Language: Shropshire Place

Learning the Landscape through Language: Shropshire Place-Names and Childhood Education Teacher and Educator Training days: Bishop’s Castle and Shrewsbury https://www.learningthroughlanguage.co.uk/competition https://www.learningth roughlanguage.co.uk/d ownloadable-resources ‘clearing by a Melverley mill-ford’ Mytton Anglo-Saxons and ‘river junction Montford the River Severn settlement’ Bridge Emstrey Shrewsbury ‘bridge by the ford where people gather’ Atcham ‘Fortified place Buildwas of the scrubland’ ‘place that floods and drains rapidly’ ‘Minster church on an island’ ‘Eata’s land in Colemore ‘cool moor’ a river-bend’ Green Melverley Welcome to Bridgnorth Melverley! You have ‘north bridge’ Danesford been completely Quatford distracted by the new ‘hidden ford’ mill there. Miss one turn. ‘ford in a district called Cwatt’ ‘clearing by a Melverley mill-ford’ Mytton Anglo-Saxons and ‘river junction Montford the River Severn settlement’ Bridge Emstrey Shrewsbury ‘bridge by the ford where people gather’ Atcham ‘Fortified place Buildwas of the scrubland’ ‘place that floods and drains rapidly’ ‘Minster church on an island’ ‘Eata’s land in Colemore Green ‘cool moor’ a river-bend’ Mytton Oh dear! Although you Bridgnorth know that Mytton means ‘north bridge’ ‘river junction settlement’, Danesford Quatford you’ve taken the wrong ‘hidden ford’ turn onto the River Perry! Go back to Montford Bridge. ‘ford in a district called Cwatt’ ‘clearing by a Melverley mill-ford’ Mytton Anglo-Saxons and ‘river junction Montford the River Severn settlement’ Bridge Emstrey Shrewsbury ‘bridge by the ford where people gather’ Atcham ‘Fortified place Buildwas of the scrubland’ ‘place that floods and drains rapidly’ ‘Minster church on an island’ ‘Eata’s land in Colemore ‘cool moor’ a river-bend’ Buildwas Green Ooh! The ‘was’ part of Buildwas means Bridgnorth ‘flood’. -

Freehold / Leasehold Mixed Use Development Opportunities

LorM54 ON BEHALF OF A5 THE SITE A5 FREEHOLD / LEASEHOLD NORTH WALES MIXED USE DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES EMSTREY ISLAND, THIEVES LANE, SHREWSBURY, SY2 6LG • Highly Prominent Freehold or Leasehold Design & Build Options. • Next to recently completed Dealership, PFS and Drive Thru’ properties. • Adjacent to established Shrewsbury Business Park. • Serviced plots available from 0.5 - 8 acres to meet occupier’s specific requirements. FREEHOLD / LEASEHOLD - MIXED USE DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES ON BEHALF OF HOME LOCATION OPPORTUNITY PLANNING FURTHER INFORMATION LOCATION L LANE WAL COT The site occupies a highly prominent position with 3 A5 HIGH ERCALL A5 extensive frontage to the A5 Shrewsbury Bypass and 124 LANE DEN BATTLEFIELD RO the B4380 Thieves Lane at Emstrey Island roundabout. A C 4 O 4 Located on the southern fringe of Shrewsbury the site is B T 2 E W R A LL W R strategically positioned opposite Shrewsbury Business 8 T OA I 2 S D C 5 K ’S A L Park and 2 miles East of Meole Brace Retail Park, with R E 2 D A 2 06 D 506 A B5 H B R C 4 I M Shrewsbury Town Centre approximately 4 miles north. 9 M A T H S L E SHREWSBURY STATION P Y The A5 is a primary trunk road running east to west, A W ADMASTON which has an annual average daily traffic flow of over E G A 6 B RD 28,000 vehicles (DfT). Linking directly to the M54 and 3 8 H B4 SHREWSBURY RC BI Telford to the east and beyond to Birmingham (45 miles) RD AW K THE SITE H O W S O A B 1 E 5 and the wider West Midlands motorway network.