Some Notes on Delius and His Music Author(S): Philip Heseltine Source: the Musical Times, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

Le Saxophone: La Voix De La Musique Moderne an Honors

Le Saxophone: La Voix de La Musique Moderne An Honors Thesis by Nathan Bancroft Bogert Dr. George Wolfe Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April 2008 May 3, 2008 Co Abstract This project was designed to display the versatility of the concert saxophone. In order to accomplish this lofty goal, a very diverse selection of repertoire was chosen to reflect the capability of the saxophone to adapt to music of all different styles and time periods. The compositions ranged from the Baroque period to even a new composition written specifically for this occasion (written by BSU School of Music professor Jody Nagel). The recital was given on February 21, 2008 in Sursa Hall on the Ball State University campus. This project includes a recording of the performance; both original and compiled program notes, and an in-depth look into the preparation that went into this project from start to finish. Acknowledgements, I would like to thank Dr. George Wolfe for his continued support of my studies and his expert guidance. Dr. Wolfe has been an incredible mentor and has continued his legacy as a teacher of the highest caliber. I owe a great deal of my success to Dr. Wolfe as he has truly made countless indelible impressions on my individual artistry. I would like to thank Dr. James Ruebel of the Ball State Honors College for his dedication to Ball State University. His knowledge and teaching are invaluable, and his dedication to his students are tings that make him the outstanding educator that he is. I would like to thank the Ball State School of Music faculty for providing me with so many musical opportunities during my time at Ball State University. -

Manuel De Falla's Homenajes for Orchestra Ken Murray

Manuel de Falla's Homenajes for orchestra Ken Murray Manuel de Falla's Homenajes suite for or- accepted the offer hoping that conditions in Ar- chestra was written in Granada in 1938 and given gentina would be more conducive to work than in its first performance in Buenos Aires in 1939 war-tom Spain. So that he could present a new conducted by the composer. It was Falla's first work at these concerts, Falla worked steadily on major work since the Soneto a Co'rdoba for voice the Homenajes suite before leaving for Argentina. and harp (1927) and his first for full orchestra On the arrival of Falla and his sister Maria del since El sombrero de tres picos, first performed in Carmen in Buenos Aires on 18 October 1939 the 1919. In the intervening years Falla worked on suite was still not ~omplete.~After a period of Atldntida (1926-46), the unfinished work which revision and rehearsal, the suite was premiered on he called a scenic cantata. Falla died in 1946 and 18 ~ovember1939 at the Teatro Col6n in Buenos the Homenajes suite remains his last major original Aires. Falla and Maria del Carmen subsequently work. The suite consists of four previously remained in Argentina where Falla died on 14 composed pieces: Fanfare sobre el nombre de November 1946. Arbds (1933); orchestrations of the Homenaje 'Le Three factors may have motivated Falla to tombeau de Claude Debussy' (1920) for solo combine these four Homenajes into an orchestral guitar; Le tombeau de Paul Dukas (1935) for pi- suite. He may have assembled the suite in order to ano; and Pedrelliana (1938) which-wasconceived give a premiere performance in Argentina. -

Alfred Desenclos

FRENCH SAXOPHONE QUARTETS Dubois Pierné Françaix Desenclos Bozza Schmitt Kenari Quartet French Saxophone Quartets Dubois • Pierné • Françaix • Desenclos • Bozza • Schmitt Invented in Paris in 1846 by Belgian-born Adolphe Sax, conductor of the Concerts Colonne series in 1910, Alfred Desenclos (1912-71) had a comparatively late The Andante et Scherzo, composed in 1943, is the saxophone was readily embraced by French conducting the world première of Stravinsky’s ballet The start in music. During his teenage years he had to work to dedicated to the Paris Quartet. This enjoyable piece is composers who were first to champion the instrument Firebird on 25th June 1910 in Paris. support his family, but in his early twenties he studied the divided into two parts. A tenor solo starts the Andante through ensemble and solo compositions. The French Pierné’s style is very French, moving with ease piano at the Conservatory in Roubaix and won the Prix de section and is followed by a gentle chorus with the other tradition, expertly demonstrated on this recording, pays between the light and playful to the more contemplative. Rome in 1942. He composed a large number of works, saxophones. The lyrical quality of the melodic solos homage to the élan, esprit and elegance delivered by this The Introduction et variations sur une ronde populaire which being mostly melodic and harmonic were often continues as the accompaniment becomes busier. The unique and versatile instrument. was composed in 1936 and dedicated to the Marcel Mule overlooked in the more experimental post-war period. second section is fast and lively, with staccato playing and Pierre Max Dubois (1930-95) was a French Quartet. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Delius Sea Drift • Songs of Farewell • Songs of Sunset

DELIUS SEA DRIFT • SONGS OF FAREWELL • SONGS OF SUNSET Bournemouth Symphony Bryn Terfel baritone Orchestra with Choirs Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Richard Hickox Greg Barrett Richard Hickox (1948 – 2008) Frederick Delius (1862 – 1934) 1 Sea Drift* 26:00 for baritone, chorus, and orchestra Songs of Farewell 18:04 for double chorus and orchestra 2 I Double Chorus: ‘How sweet the silent backward tracings!’ 4:28 3 II Chorus: ‘I stand as on some mighty eagle’s beak’ 4:39 4 III Chorus: ‘Passage to you! O secret of the earth and sky!’ 3:33 5 IV Double Chorus: ‘Joy, shipmate, joy!’ 1:31 6 V Chorus: ‘Now finalè to the shore’ 3:50 3 Songs of Sunset*† 32:59 for mezzo-soprano, baritone, chorus, and orchestra 7 Chorus: ‘A song of the setting sun!’ – 3:24 8 Soli: ‘Cease smiling, Dear! a little while be sad’ – 4:46 9 Chorus: ‘Pale amber sunlight falls…’ – 4:26 10 Mezzo-soprano: ‘Exceeding sorrow Consumeth my sad heart!’ – 3:43 11 Baritone: ‘By the sad waters of separation’ – 4:49 12 Chorus: ‘See how the trees and the osiers lithe’ – 3:35 13 Baritone: ‘I was not sorrowful, I could not weep’ – 4:46 14 Soli, Chorus: ‘They are not long, the weeping and the laughter’ 3:34 TT 77:20 Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano† Bryn Terfel baritone* Waynflete Singers David Hill director Southern Voices Graham Caldbeck chorus master Members of the Bournemouth Symphony Chorus Neville Creed chorus master Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Brendan O’Brien leader Richard Hickox 4 Delius: Sea Drift / Songs of Sunset / Songs of Farewell Sea Drift into which the chorus’s commentaries are Both Sea Drift (1903 – 04) and Songs of Sunset effortlessly intermingled. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’

‘The Art-Twins of Our Timestretch’: Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’ Catherine Sarah Kirby Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Music (Musicology) April 2015 Melbourne Conservatorium of Music The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis explores Percy Grainger’s promotion of the music of Frederick Delius in the United States of America between his arrival in New York in 1914 and Delius’s death in 1934. Grainger’s ‘Delius campaign’—the title he gave to his work on behalf of Delius— involved lectures, articles, interviews and performances as both a pianist and conductor. Through this, Grainger was responsible for a number of noteworthy American Delius premieres. He also helped to disseminate Delius’s music by his work as a teacher, and through contact with publishers, conductors and the press. In this thesis I will examine this campaign and the critical reception of its resulting performances, and question the extent to which Grainger’s tireless promotion affected the reception of Delius’s music in the USA. To give context to this campaign, Chapter One outlines the relationship, both personal and compositional, between Delius and Grainger. This is done through analysis of their correspondence, as well as much of Grainger’s broader and autobiographical writings. This chapter also considers the relationship between Grainger, Delius and others musicians within their circle, and explores the extent of their influence upon each other. Chapter Two examines in detail the many elements that made up the ‘Delius campaign’. -

FLORENT SCHMITT Mélodies

FLORENT SCHMITT Mélodies Sybille Diethelm soprano Annina Haug mezzo-soprano Nino Aurelio Gmünder tenor René Perler bass-baritone Fabienne Romer piano Edward Rushton piano Florent Schmitt (1870–1958) Chansons à quatre voix, Op. 39 (1905) Quatre Poèmes de Ronsard, Op. 100 (1942) 1. Véhémente [1:22] 19. Si… [2:36] Mélodies 2. Nostalgique [2:01] 20. Privilèges [1:42] 3. Naïve [2:51] 21. Ses deux yeux [2:49] 4. Boréale [1:26] 22. Le soir qu’Amour [3:02] 5. Tendre [4:12] 1–6, 11–13 & 23–25 Sybille Diethelm soprano 6. Marale [1:48] Trois Chants, Op. 98 (1943) Annina Haug mezzo soprano 1–6 & 17–18 23. Elle était venue [5:13] Nino Aurelio Gmünder tenor 1–10 & 19–22 Quatre Lieds, Op. 45 (1912) 24. La citerne des mille René Perler bass-baritone 1–6 & 14–16 7. Où vivre? [1:32] colonnes – Yéré Batan [6:07] Fabienne Romer piano 1–10, 17–18 & 23–25 8. Evocaon [1:38] 25. La tortue et le 1–6, 11–16 & 19–22 9. Fleurs décloses [2:23] lièvre – Fable [4:06] Edward Rushton piano 10. Ils ont tué trois petes filles [2:51] Kérob-Shal, Op. 67 (1924) Total playing me [72:33] 11. Octroi [3:55] 12. Star [2:16] 13. Vendredi XIII [3:38] All world premiere recordings apart Trois Mélodies, Op. 4 (1895) from Op. 98, Op. 100 & Op. 4, No. 2 14. Lied [3:11] 15. Il pleure dans mon coeur [2:57] 16. Fils de la Vierge [2:44] Deux Chansons, Op. -

Wilson Poffenberger, Saxophone

KRANNERT CENTER DEBUT ARTIST: WILSON POFFENBERGER, SAXOPHONE CASEY GENE DIERLAM, PIANO Sunday, April 14, 2019, at 3pm Foellinger Great Hall PROGRAM KRANNERT CENTER DEBUT ARTIST: WILSON POFFENBERGER, SAXOPHONE Casey Gene Dierlam, piano Maurice Ravel Ma Mère L’Oye (“Mother Goose”) (1875-1937) Pavane de la Belle au bois dormant (arr. by Wilson Poffenberger) Petit Poucet Laideronnette, Impératrice des Pagodes Les entretiens de la Belle et de la Bête Le jardin férique Florent Schmitt Légende, Op. 66 (1870-1958) Gabriel Fauré Après un rêve, Op. 7, No. 1 (1845-1924) (arr. by Wilson Poffenberger) 20-minute intermission Johann Sebastian Bach Partita No. 2 in D Minor for Solo Violin, BWV 1004 (1685-1750) Allemande (arr. by Wilson Poffenberger) Edison Denisov Sonate (1929-1996) Allegro Lento Allegro moderato Fernande Decruck Sonate en Ut# (1896-1954) Trés modéré, espressif Noël Fileuse Nocturne et Final 2 THE ACT OF GIVING OF ACT THE THANK YOU FOR SPONSORING THIS PERFORMANCE With deep gratitude, Krannert Center thanks all 2018-19 Patron Sponsors and Corporate and Community Sponsors, and all those who have invested in Krannert Center. Please view their names later in this program and join us in thanking them for their support. This event is supported by: * TERRY & BARBARA ENGLAND LOUISE ALLEN Four Previous Sponsorships Twelve Previous Sponsorships * NADINE FERGUSON ANONYMOUS Nine Previous Sponsorships Four Previous Sponsorships *PHOTO CREDIT: ILLINI STUDIO HELP SUPPORT THE FUTURE OF THE ARTS. BECOME A KRANNERT CENTER SPONSOR BY CONTACTING OUR ADVANCEMENT TEAM TODAY: KrannertCenter.com/Give • [email protected] • 217.333.1629 3 PROGRAM NOTES The art of transcription is celebrated by Wilson The first of the five pieces, “Pavane de la Belle Poffenberger’s demanding work for this program. -

The Choral Cycle

THE CHORAL CYCLE: A CONDUCTOR‟S GUIDE TO FOUR REPRESENTATIVE WORKS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY RUSSELL THORNGATE DISSERTATION ADVISORS: DR. LINDA POHLY AND DR. ANDREW CROW BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2011 Contents Permissions ……………………………………………………………………… v Introduction What Is a Choral Cycle? .............................................................................1 Statement of Purpose and Need for the Study ............................................4 Definition of Terms and Methodology .......................................................6 Chapter 1: Choral Cycles in Historical Context The Emergence of the Choral Cycle .......................................................... 8 Early Predecessors of the Choral Cycle ....................................................11 Romantic-Era Song Cycles ..................................................................... 15 Choral-like Genres: Vocal Chamber Music ..............................................17 Sacred Cyclical Choral Works of the Romantic Era ................................20 Secular Cyclical Choral Works of the Romantic Era .............................. 22 The Choral Cycle in the Twentieth Century ............................................ 25 Early Twentieth-Century American Cycles ............................................. 25 Twentieth-Century European Cycles ....................................................... 27 Later Twentieth-Century American -

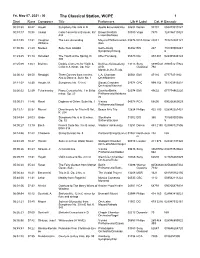

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Fri, May 07, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 30:47 Haydn Symphony No. 042 in D Apollo Ensemble/Hsu 02698 Dorian 90191 053479019127 00:33:1710:38 Vivaldi Cello Concerto in B minor, RV Brown/Scottish 03080 Virgo 7873 724356110328 424 Ensemble/Rees 00:44:5514:31 Vaughan The Lark Ascending Meyers/Philharmonia/L 03876 RCA Victor 23041 743212304121 Williams itton 01:00:5621:29 Nielsen Suite from Aladdin Gothenburg 06392 BIS 247 731859000247 Symphony/Chung 6 01:23:2501:14 Schubert The Youth at the Spring, D. Otter/Forsberg 05373 DG 453 481 028945348124 300 01:25:3933:03 Brahms Double Concerto for Violin & Bell/Isserlis/Academy 13113 Sony 88985321 889853217922 Cello in A minor, Op. 102 of St. Classical 792 Martin-in-the-Fields 02:00:1209:50 Respighi Three Dances from Ancient L.A. Chamber 00561 EMI 47116 07777471162 Airs & Dances, Suite No. 1 Orch/Marriner 02:11:02 14:30 Haydn, M. Symphony No. 12 in G Slovak Chamber 02578 CPO 999 154 761203915422 Orchestra/Warchal 02:26:3232:29 Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat Gavrilov/Berlin 02074 EMI 49632 077774963220 minor, Op. 23 Philharmonic/Ashkena zy 03:00:3111:46 Ravel Daphnis et Chloe: Suite No. 1 Vienna 04578 RCA 68600 090266860029 Philharmonic/Maazel 03:13:1720:37 Mozart Divertimento for Trio in B flat, Beaux Arts Trio 12824 Philips 422 700 028942251427 K. 254 03:34:5424:03 Gade Symphony No. 6 in G minor, Stockholm 01002 BIS 355 731859000356 Op.