FLORENT SCHMITT Mélodies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Saxophone: La Voix De La Musique Moderne an Honors

Le Saxophone: La Voix de La Musique Moderne An Honors Thesis by Nathan Bancroft Bogert Dr. George Wolfe Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April 2008 May 3, 2008 Co Abstract This project was designed to display the versatility of the concert saxophone. In order to accomplish this lofty goal, a very diverse selection of repertoire was chosen to reflect the capability of the saxophone to adapt to music of all different styles and time periods. The compositions ranged from the Baroque period to even a new composition written specifically for this occasion (written by BSU School of Music professor Jody Nagel). The recital was given on February 21, 2008 in Sursa Hall on the Ball State University campus. This project includes a recording of the performance; both original and compiled program notes, and an in-depth look into the preparation that went into this project from start to finish. Acknowledgements, I would like to thank Dr. George Wolfe for his continued support of my studies and his expert guidance. Dr. Wolfe has been an incredible mentor and has continued his legacy as a teacher of the highest caliber. I owe a great deal of my success to Dr. Wolfe as he has truly made countless indelible impressions on my individual artistry. I would like to thank Dr. James Ruebel of the Ball State Honors College for his dedication to Ball State University. His knowledge and teaching are invaluable, and his dedication to his students are tings that make him the outstanding educator that he is. I would like to thank the Ball State School of Music faculty for providing me with so many musical opportunities during my time at Ball State University. -

Manuel De Falla's Homenajes for Orchestra Ken Murray

Manuel de Falla's Homenajes for orchestra Ken Murray Manuel de Falla's Homenajes suite for or- accepted the offer hoping that conditions in Ar- chestra was written in Granada in 1938 and given gentina would be more conducive to work than in its first performance in Buenos Aires in 1939 war-tom Spain. So that he could present a new conducted by the composer. It was Falla's first work at these concerts, Falla worked steadily on major work since the Soneto a Co'rdoba for voice the Homenajes suite before leaving for Argentina. and harp (1927) and his first for full orchestra On the arrival of Falla and his sister Maria del since El sombrero de tres picos, first performed in Carmen in Buenos Aires on 18 October 1939 the 1919. In the intervening years Falla worked on suite was still not ~omplete.~After a period of Atldntida (1926-46), the unfinished work which revision and rehearsal, the suite was premiered on he called a scenic cantata. Falla died in 1946 and 18 ~ovember1939 at the Teatro Col6n in Buenos the Homenajes suite remains his last major original Aires. Falla and Maria del Carmen subsequently work. The suite consists of four previously remained in Argentina where Falla died on 14 composed pieces: Fanfare sobre el nombre de November 1946. Arbds (1933); orchestrations of the Homenaje 'Le Three factors may have motivated Falla to tombeau de Claude Debussy' (1920) for solo combine these four Homenajes into an orchestral guitar; Le tombeau de Paul Dukas (1935) for pi- suite. He may have assembled the suite in order to ano; and Pedrelliana (1938) which-wasconceived give a premiere performance in Argentina. -

Alfred Desenclos

FRENCH SAXOPHONE QUARTETS Dubois Pierné Françaix Desenclos Bozza Schmitt Kenari Quartet French Saxophone Quartets Dubois • Pierné • Françaix • Desenclos • Bozza • Schmitt Invented in Paris in 1846 by Belgian-born Adolphe Sax, conductor of the Concerts Colonne series in 1910, Alfred Desenclos (1912-71) had a comparatively late The Andante et Scherzo, composed in 1943, is the saxophone was readily embraced by French conducting the world première of Stravinsky’s ballet The start in music. During his teenage years he had to work to dedicated to the Paris Quartet. This enjoyable piece is composers who were first to champion the instrument Firebird on 25th June 1910 in Paris. support his family, but in his early twenties he studied the divided into two parts. A tenor solo starts the Andante through ensemble and solo compositions. The French Pierné’s style is very French, moving with ease piano at the Conservatory in Roubaix and won the Prix de section and is followed by a gentle chorus with the other tradition, expertly demonstrated on this recording, pays between the light and playful to the more contemplative. Rome in 1942. He composed a large number of works, saxophones. The lyrical quality of the melodic solos homage to the élan, esprit and elegance delivered by this The Introduction et variations sur une ronde populaire which being mostly melodic and harmonic were often continues as the accompaniment becomes busier. The unique and versatile instrument. was composed in 1936 and dedicated to the Marcel Mule overlooked in the more experimental post-war period. second section is fast and lively, with staccato playing and Pierre Max Dubois (1930-95) was a French Quartet. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

000000018 1.Pdf

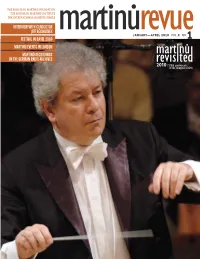

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE THE INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE INTERVIEW WITH CONDUCTOR JIŘÍ BĚLOHLÁVEK martinůJANUARY—APRILrevue 2010 VOL.X NO. FESTIVAL IN BASEL 2009 1 MARTINŮ EVENTS IN LONDON MARTINŮ RECORDINGS ķ IN THE GERMAN RADIO ARCHIVES contents 3 Martinů Revisited Highlights 4 news —Anna Fárová Dies —Zdeněk Mácal’s Gift 5 International Martinů Circle 6 festivals —The Fruit of Diligent and Relentless Activity CHRISTINE FIVIAN 8 interview …with Jiří Bělohlávek ALEŠ BŘEZINA 9 Liturgical Mass in Prague MILAN ČERNÝ 10 News from Polička LUCIE JIRGLOVÁ UP 0121-2 11 special series —List of Martinů’s Works VIII 12 research —Martinů Treasures in the German Radio Archives GREGORY TERIAN 13 review —Martinů in Scotland GREGORY TERIAN 14 review —Czech Festival in London UP 0123-2 UP 0126-2 PATRICK LAMBERT 16 festivals —Bohuslav Martinů Days 2009 PETR VEBER 17 news / conference 18 events 19 news UP 0106-2 UP 0122-2 UP 0116-2 —New CDs, Publications ARCODIVA Jaromírova 48, 128 00 Praha 2, Czech Republic tel.: +420 223 006 934, +420 777 687 797 • fax: +420 223 006 935 e-mail: [email protected] ķ highlights IN 2010 TOO WE ARE CELEBRATING a momentous anniversary – 120 years since the birth of Bohuslav Martinů (8 December 1890, Polička). Numerous ensembles and music organisations have included Martinů works in their 2010 repertoire. We will keep you up to date on this page with the most significant events. MORE INFORMATION > www.martinu.cz > www.czechmusic.org ‹vFESTIVALS—› The 65th Prague Spring The 65th PRAGUE SPRING INTERNATIONAL MUSIC FESTIVAL International Music Festival Prague, 12 May—4 June 2010 Prague / 12 May—4 June 2010 www.festival.cz 15 May 2010, 11.00 am > Martinů Hall, Lichtenštejn Palace Scherzo, H. -

Wilson Poffenberger, Saxophone

KRANNERT CENTER DEBUT ARTIST: WILSON POFFENBERGER, SAXOPHONE CASEY GENE DIERLAM, PIANO Sunday, April 14, 2019, at 3pm Foellinger Great Hall PROGRAM KRANNERT CENTER DEBUT ARTIST: WILSON POFFENBERGER, SAXOPHONE Casey Gene Dierlam, piano Maurice Ravel Ma Mère L’Oye (“Mother Goose”) (1875-1937) Pavane de la Belle au bois dormant (arr. by Wilson Poffenberger) Petit Poucet Laideronnette, Impératrice des Pagodes Les entretiens de la Belle et de la Bête Le jardin férique Florent Schmitt Légende, Op. 66 (1870-1958) Gabriel Fauré Après un rêve, Op. 7, No. 1 (1845-1924) (arr. by Wilson Poffenberger) 20-minute intermission Johann Sebastian Bach Partita No. 2 in D Minor for Solo Violin, BWV 1004 (1685-1750) Allemande (arr. by Wilson Poffenberger) Edison Denisov Sonate (1929-1996) Allegro Lento Allegro moderato Fernande Decruck Sonate en Ut# (1896-1954) Trés modéré, espressif Noël Fileuse Nocturne et Final 2 THE ACT OF GIVING OF ACT THE THANK YOU FOR SPONSORING THIS PERFORMANCE With deep gratitude, Krannert Center thanks all 2018-19 Patron Sponsors and Corporate and Community Sponsors, and all those who have invested in Krannert Center. Please view their names later in this program and join us in thanking them for their support. This event is supported by: * TERRY & BARBARA ENGLAND LOUISE ALLEN Four Previous Sponsorships Twelve Previous Sponsorships * NADINE FERGUSON ANONYMOUS Nine Previous Sponsorships Four Previous Sponsorships *PHOTO CREDIT: ILLINI STUDIO HELP SUPPORT THE FUTURE OF THE ARTS. BECOME A KRANNERT CENTER SPONSOR BY CONTACTING OUR ADVANCEMENT TEAM TODAY: KrannertCenter.com/Give • [email protected] • 217.333.1629 3 PROGRAM NOTES The art of transcription is celebrated by Wilson The first of the five pieces, “Pavane de la Belle Poffenberger’s demanding work for this program. -

A Village Romeo and Juliet the Song of the High Hills Irmelin Prelude

110982-83bk Delius 14/6/04 11:00 am Page 8 Also available on Naxos Great Conductors • Beecham ADD 8.110982-83 DELIUS A Village Romeo and Juliet The Song of the High Hills Irmelin Prelude Dowling • Sharp • Ritchie Soames • Bond • Dyer Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Sir Thomas Beecham Naxos Radio (Recorded 1946–1952) Over 50 Channels of Classical Music • Jazz, Folk/World, Nostalgia Accessible Anywhere, Anytime • Near-CD Quality www.naxosradio.com 2 CDs 8.110982-83 8 110982-83bk Delius 14/6/04 11:00 am Page 2 Frederick Delius (1862-1934) 5 Koanga: Final Scene 9:07 Royal Philharmonic Orchestra • Sir Thomas Beecham (1879-1961) (Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus) Recorded on 26th January, 1951 Delians and Beecham enthusiasts will probably annotation, frequently content with just the notes. A Matrix Nos. CAX 11022-3, 11023-2B continue for ever to debate the relative merits of the score of a work by Delius marked by Beecham, First issued on Columbia LX 1502 earlier recordings made by the conductor in the 1930s, however, tells a different story, instantly revealing a mostly with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, in most sympathetically engaged music editor at work. comparison with those of the 1940s and 1950s Pulse, dynamics, phrasing, expressive nuance and All recordings made in Studio 1, Abbey Road, London recorded with handpicked players of the Royal articulation, together with an acute sensitivity to Transfers & Production: David Lennick Philharmonic Orchestra. Following these two major constantly changing orchestral balance, are annotated Digital Noise Reduction: K&A Productions Ltd. periods of activity, the famous EMI stereo remakes with painstaking practical detail to compliment what Original recordings from the collections of David Lennick, Douglas Lloyd and Claude G. -

BMN 2002/2.Indd

Bohuslav Martinů May – August 2002 Always Slightly off Center An Interview with Christopher Hogwood When the Fairies Learned to Walk Feuilleton on The Three Wishes in Augsburg Second The Wonderful Flights issue It Was a Dream for Me to Have a Piece by Martinů Jiří Tancibudek and Concerto for Oboe and Small Orchestra 25 Years of the Martinů Quartet Bats in the Belfry The Film Victims and Murderers Martinů News and Events The International Bohuslav Martinů Society The Bohuslav Martinů Institute CONTENTS WELCOME Karel Van Eycken ....................................... 3 BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ SOCIETIES AROUND THE WORLD .................................. 3 ALWAYS SLIGHTLY OFF CENTER Christopher Hogwood interviewed by Aleš Březina ..................................... 4 - 6 REVIEW Sandra Bergmannová ................................. 7 WHEN THE FAIRIES LEARNED TO WALK Feuilleton on The Three Wishes in Augsburg Jörn Peter Hiekel .......................................8 BATS IN THE BELFRY The Film Victims and Murderers Patrick Lambert ........................................ 9 MARTINŮ EVENTS 2002 ........................10 - 11 THE WONDERFUL FLIGHTS Gregory Terian .........................................12 THE CZECH RHAPSODY IN A NEW GARB Adam Klemens .........................................13 25 YEARS OF THE MARTINŮ QUARTET Eva Vítová, Jana Honzíková ........................14 “MARTINŮ WAS A GREAT MUSICIAN, UNFORGETTABLE…” Announcement about Margrit Weber ............15 IT WAS A DREAM FOR ME TO HAVE A PIECE BY MARTINŮ Jiří Tancibudek and Concerto -

Steve Carmichael DMA Saxophone Recital

About the Artists Steve Carmichael is a candidate for the Doctor of Musical Arts, Saxophone Performance, with a minor in Jazz Studies at the University Of Wisconsin – Madison where he is a student of Les Thimmig. Formerly he was Director of Jazz Studies at Carthage College, Kenosha, Wisconsin. Having served 20 years as a saxophone and flute instrumentalist with the US Navy Bands, he has performed for audiences in over 40 countries, including France, Italy, China, Russia, Australia, Germany, England, Jakarta, Hong Kong, Japan, Scotland, and many others. He has been awarded two Navy Achievement Medals and a Navy Commendation Medal for his leadership as Big Band and Saxophone Quartet director. He has performed as section and solo saxophonist with the San Diego Steve Carmichael Symphony, Chattanooga Symphony, NHK Tokyo Symphony, Chicago’s Northshore Concert Band, Spectrum Saxophone Quartet, the San Diego Wind Ensemble, The Nelson Riddle Orchestra, and with such artist as Bill Holman, DMA Saxophone Recital Louie Bellson, Bill Watrous, Kim Richmond, Pete Christleib, Dave Leibman, Clark Terry, Mike Vax, Florence Henderson, Harry Connick Sr, and Nancy Wilson. Pianist Joseph Ross is an experienced solo performer, chamber musician and accompanist. He has studied and appeared in concert in the United States, Assisted by Canada and Europe. Ross has held positions at Lawrence University, the University of Wisconsin – Madison and the Hungarian State Opera. Joseph Ross, Piano Mr. Ross holds a MM from the Franz Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest, Hungary and a BM degree at Lawrence University. Mikko Utevsky, Viola Mikko Utevsky is a violist and conductor studying at the UW-Madison. -

Newsletter 2-2005

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION & THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE MAY—AUGUST 2005 The Greek Passion / VOL. Finally in Greece V / NO. Interview with Neeme Järvi 2 Martinů & Hans Kindler The Final Years ofthe Life of Bohuslav Martinů Antonín Tučapský on Martinů NEWS & EVENTS ts– Conten VOL. V / NO.2 MAY—AUGUST 2005 Bohuslav Martinů in Liestal, May 1956 > Photo from Max Kellerhals’archive e WelcomE —EDITORIAL —REPORT OF MAY SYMPOSIUM OF EDITORIAL BOARD —INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE r Reviews —BBC SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA —CD REVIEWS —GILGAMESH y Reviews f Research THE GREEK PASSION THE FINAL YEARS OF THE FINALLY IN GREECE LIFE OF BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ • ALEŠ BŘEZINA • LUCIE BERNÁ u Interview j Memoirs WITH… NEEME JÄRVI ANTONÍN TUČAPSKÝ • EVA VELICKÁ ON MARTINŮ i Research k Events MARTINŮ & HANS KINDLER —CONCERTS • F. JAMES RYBKA & BORIS I. RYBKA —BALLETS —FESTIVALS a Memoirs l News MEMORIES OF —THE MARTINŮ INSTITUTE’S CORNER MONSIEUR MARTINŮ —NEW RECORDING —OBITUARIES • ADRIAN SCHÜRCH —BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ DISCUSSION GROUP me– b Welco THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ REPORT ON THE MAY SYMPOSIUM OF THE EDITORIAL NEWSLETTER is published by the Bohuslav Martinů EDITORIAL BOARD Foundation in collaboration with the DEAR READERS, Bohuslav Martinů Institute in Prague THE MEETING of the editorial board in 2005 was held on 14–15 May in the premises we are happy to present the new face of the Bohuslav Martinů Institute. It was attended by the chair of the editorial board of the Bohuslav Martinů Newsletter, EDITORS Aleš Březina as well as Sandra Bergmannová of the Charles University Institute of published by the Bohuslav Martinů Zoja Seyčková Musicology and the Bohuslav Martinů Institute, Dietrich Berke, Klaus Döge of the Foundation and Institute.We hope you Jindra Jilečková Richard Wagner-Gesamtausgabe, Jarmila Gabrielová of the Charles University Institute will enjoy the new graphical look. -

3149028007312.Pdf

Enregistré par Little Tribeca au Temple Saint-Pierre (Paris) en mai 2016. Sandrine Chatron joue une harpe Lyon & Healy Style 30. Remerciements pour leur soutien à la Fondation Marcelle et Robert de Lacour, à l’Instrumentarium, à Mécénat 100% ainsi qu’à Ian Mylett, Desmond Scott et Pascaline Mulliez. Direction artistique : Ignace Hauville Prise de son : Nicolas Bartholomée et Ignace Hauville Montage et mixage : Ignace Hauville Introduction de Laura Tunbridge Traductions par Dennis Collins Photos © Caroline Doutre Design © 440.media AP140 Little Tribeca p 2016 © 2017 1, rue Paul Bert 93500 Pantin, France apartemusic.com A BRITISH PROMENADE SANDRINE CHATRON harp OPHÉLIE GAILLARD cello - MICHAEL BENNETT tenor YORK BOWEN (1884-1961) 1. Arabesque - Arabesque (1932)* 6’41 HERBERT HOWELLS (1892-1983) 2. Prelude for harp - Prélude pour harpe (1915) 5’09 SIR GRANVILLE BANTOCK (1868-1946) 3. Hamabdil (Hebrew Melody) for cello and harp Hamabdil (Mélodie hébraïque) pour violoncelle et harpe (1917) 5’05 CYRIL SCOTT (1879-1970) 4. Celtic Fantasy for harp - Fantaisie celtique pour harpe (1926)* 10’01 EUGÈNE GOOSSENS (1893-1962) 5. Ballade No. 1 for harp, Op. 38 - Ballade n° 1 pour harpe, op. 38 (1924) 3’22 6. Ballade No. 2 for harp, Op. 38 - Ballade n° 2 pour harpe, op. 38 (1924) 4’04 DAVID WATKINS (ARR.) 7. Scarborough Fair, traditional folksong (arr. for voice and harp) La Foire de Scarborough, chanson traditionnelle (arr. pour voix et harpe) 2’16 GRACE WILLIAMS (1906-1977) 8. Hiraeth for harp - Hiraeth pour harpe (1951) 2’19 LENNOX BERKELEY (1903-1989) Five Herrick Poems for tenor and harp, Op. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfiUm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in Qpewriter face, while others may be from w y type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photogr^hs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with sm all overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photogr^hs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for aiqr photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell information Com pany 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 3l3.'761-4700 800/521-0600 NOTABLE PERCUSSION EXCERPTS OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY WIND-BAND REPERTOIRE DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Charles Timothy Sivils, M.M.