Poetry and Prose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paying Attention to Public Readers of Canadian Literature

PAYING ATTENTION TO PUBLIC READERS OF CANADIAN LITERATURE: POPULAR GENRE SYSTEMS, PUBLICS, AND CANONS by KATHRYN GRAFTON BA, The University of British Columbia, 1992 MPhil, University of Stirling, 1994 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2010 © Kathryn Grafton, 2010 ABSTRACT Paying Attention to Public Readers of Canadian Literature examines contemporary moments when Canadian literature has been canonized in the context of popular reading programs. I investigate the canonical agency of public readers who participate in these programs: readers acting in a non-professional capacity who speak and write publicly about their reading experiences. I argue that contemporary popular canons are discursive spaces whose constitution depends upon public readers. My work resists the common critique that these reading programs and their canons produce a mass of readers who read the same work at the same time in the same way. To demonstrate that public readers are canon-makers, I offer a genre approach to contemporary canons that draws upon literary and new rhetorical genre theory. I contend in Chapter One that canons are discursive spaces comprised of public literary texts and public texts about literature, including those produced by readers. I study the intertextual dynamics of canons through Michael Warner’s theory of publics and Anne Freadman’s concept of “uptake.” Canons arise from genre systems that are constituted to respond to exigencies readily recognized by many readers, motivating some to participate. I argue that public readers’ agency lies in the contingent ways they select and interpret a literary work while taking up and instantiating a canonizing genre. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Bug Bites It’S Only a Matter of Time Before Insects Become a Staple of Western Diets

A PUBLICATION OF ALUMNI UBC · NUMBER 36 · 2014 BUG BITES It’s only a matter of time before insects become a staple of Western diets. PLUS Stuck in a medical minority BC’s endangered languages Dear Dr. Wesbrook: letters from the front Author Nancy Lee has The Last Word 22 16 DOUBLE FEATURE COVER THE waitinG ROOM THE BUG FARMER A powerful documentary is illustrating the Andrew Brentano, BA’10, is supporting the growth of a grassroots plight of people living with undiagnosed conditions. insect‑farming industry – starting in his own garage. AN UncOMMON EatinG InsEcts is NOT PEOPLE whO haVE A RARE disEasE OR UndiaGNOSED COnditiON can FEEL isOlatED and abandONED. DENOMinatOR “ICKY.” GET OVER IT. RaisinG awaRENEss and BUildinG SUPPORT NEtwORKS GIVES thEM The Rare Disease Foundation is using a collective Professor Murray Isman says eating insects is not only desirable, A VOicE and BOOsts thEIR HOPES approach to create a support network for patients. FOR answERS. but inevitable. THE LOVE BUG FEATURE Afton Halloran, BSc’09, co‑wrote a major UN publication InsEcts ARE A COMMON SOURCE OF NUTRitiON in ManY on the contribution of insects to global food security. 12 VANISHING PARts OF thE WORld BUT haVE YET TO BECOME a staPLE Her fascination with the subject led to a chance meeting. OF WEstERN diEts. THERE ARE stRONG ARGUMEnts FOR OVERCOMinG ANY AVERsiON. VOicES Language activists are determined to bring BC’s indigenous tongues back from the brink of extinction. In Short QUOTE, UNQUOTE 52 3 3 FEATURE Q&A 4 TaKE NOTE 28 DEar 6 ABORIGIN AL GANGS DR. -

49Th USA Film Festival Schedule of Events

HIGH FASHION HIGH FINANCE 49th Annual H I G H L I F E USA Film Festival April 24-28, 2019 Angelika Film Center Dallas Sienna Miller in American Woman “A R O L L E R C O A S T E R O F FABULOUSNESS AND FOLLY ” FROM THE DIRECTOR OF DIOR AND I H AL STON A F I L M B Y FRÉDERIC TCHENG prODUCeD THE ORCHARD CNN FILMS DOGWOOF TDOG preSeNT a FILM by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG IN aSSOCIaTION WITH pOSSIbILITy eNTerTaINMeNT SHarp HOUSe GLOSS “HaLSTON” by rOLaND baLLeSTer CO- DIreCTOr OF eDITeD MUSIC OrIGINaL SCrIpTeD prODUCerS STepHaNIe LeVy paUL DaLLaS prODUCer MICHaeL praLL pHOTOGrapHy CHrIS W. JOHNSON by ÈLIa GaSULL baLaDa FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG SUperVISOr TraCy MCKNIGHT MUSIC by STaNLey CLarKe CINeMaTOGrapHy by aarON KOVaLCHIK exeCUTIVe prODUCerS aMy eNTeLIS COUrTNey SexTON aNNa GODaS OLI HarbOTTLe LeSLey FrOWICK IaN SHarp rebeCCa JOerIN-SHarp eMMa DUTTON LaWreNCe beNeNSON eLySe beNeNSON DOUGLaS SCHWaLbe LOUIS a. MarTaraNO CO-exeCUTIVe WrITTeN, prODUCeD prODUCerS ELSA PERETTI HARVEY REESE MAGNUS ANDERSSON RAJA SETHURAMAN FeaTUrING TaVI GeVINSON aND DIreCTeD by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG Fest Tix On@HALSTONFILM WWW.HALSTON.SaleFILM 4 /10 IMAGE © STAN SHAFFER Udo Kier The White Crow Ed Asner: Constance Towers in The Naked Kiss Constance Towers On Stage and Off Timothy Busfield Melissa Gilbert Jeff Daniels in Guest Artist Bryn Vale and Taylor Schilling in Family Denise Crosby Laura Steinel Traci Lords Frédéric Tcheng Ed Zwick Stephen Tobolowsky Bryn Vale Chris Roe Foster Wilson Kurt Jacobsen Josh Zuckerman Cheryl Allison Eli Powers Olicer Muñoz Wendy Davis in Christina Beck -

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (AZ Listing by Episode Title. Prices Include

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (A-Z listing by episode title. Prices include taxes and shipping within Canada) Catalog is updated at the end of each month. For current month’s listings, please visit: http://www.cbc.ca/ideas/schedule/ Transcript = readable, printed transcript CD = titles are available on CD, with some exceptions due to copyright = book 104 Pall Mall (2011) CD $18 foremost public intellectuals, Jean The Academic-Industrial Ever since it was founded in 1836, Bethke Elshtain is the Laura Complex London's exclusive Reform Club Spelman Rockefeller Professor of (1982) Transcript $14.00, 2 has been a place where Social and Political Ethics, Divinity hours progressive people meet to School, The University of Chicago. Industries fund academic research discuss radical politics. There's In addition to her many award- and professors develop sideline also a considerable Canadian winning books, Professor Elshtain businesses. This blurring of the connection. IDEAS host Paul writes and lectures widely on dividing line between universities Kennedy takes a guided tour. themes of democracy, ethical and the real world has important dilemmas, religion and politics and implications. Jill Eisen, producer. 1893 and the Idea of Frontier international relations. The 2013 (1993) $14.00, 2 hours Milton K. Wong Lecture is Acadian Women One hundred years ago, the presented by the Laurier (1988) Transcript $14.00, 2 historian Frederick Jackson Turner Institution, UBC Continuing hours declared that the closing of the Studies and the Iona Pacific Inter- Acadians are among the least- frontier meant the end of an era for religious Centre in partnership with known of Canadians. -

Burke Keynote Speaker Commencement, Page 21

Burke Keynote Speaker Commencement, Page 21 Classified, Page 26 Classified, ❖ ABC News Reporter Jennifer Donelan, a native of Fairfax County, gave the keynote address for the June 17 Lake Braddock Secondary Commencement. Donelan could not emphasize enough that this moment is a Real Estate, Page 16 Real Estate, ❖ milestone and a stepping off point to the future. Camps & Schools, Page 11 Camps & Schools, ❖ Faith, Page 23 ❖ Sports, Page 24 insideinside Requested in home 6-20-08 Time sensitive material. Attention Postmaster: U.S. Postage Word Out PRSRT STD PERMIT #322 Easton, MD On Repairs Koger Firm PAID News, Page 3 Auctioned Off News, Page 3 Photo By Louise Krafft/The Connection By Louise Krafft/The Photo www.connectionnewspapers.com www.ConnectionNewspapers.com June 19-25, 2008 Volume XXII, Number 25 Burke Connection ❖ June 19-25, 2008 ❖ 1 2 ❖ Burke Connection ❖ June 19-25, 2008 www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Burke Connection Editor Michael O’Connell News 703-917-6440 or [email protected] 2 Cases, 2 Courts, Same Day Groner gave Koger his Jeffrey Koger appears in Miranda rights en route to court on attempted capital Inova Fairfax Hospital. “You are under arrest for murder of police officer. attempted capital murder Koger Firm Sold of a police officer,” Groner told Koger, who was admit- Sheriff’s Photo Sheriff’s By Ken Moore ted to the hospital in criti- Troubled management firm The Connection cal condition. On Tuesday, June 17, auctioned in bankruptcy court. effrey Scott Koger held a shotgun Judge Penney S. Azcarate against his shoulder and pointed the certified the case to a By Nicholas M. -

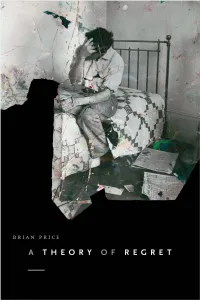

A Theory of Regret This Page Intentionally Left Blank a THEORY of REGRET

a theory of regret This page intentionally left blank A THEORY OF REGRET Brian Price duke university press · Durham and London · 2017 © 2017 duke university press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Scala by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Price, Brian, [date] author. Title: A theory of regret / Brian Price. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and cip data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017019892 (print) lccn 2017021773 (ebook) isbn 9780822372394 (ebook) isbn 9780822369363 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822369516 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Regret. Classification: lcc bf575.r33 (ebook) | lcc bf575.r33 p75 2017 (print) | ddc 158—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019892 Cover art: John Deakin, Photograph of Lucian Freud, 1964. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. / dacs, London / ars, NY 2017 for alexander garcía düttmann This page intentionally left blank We do not see our hand in what happens, so we call certain events melancholy accidents when they are the inevitabilities of our projects (I, 75), and we call other events necessities because we will not change our minds. Stanley Cavell, The Senses of Walden I now regret very much that I did not yet have the courage (or immodesty?) at that time to permit myself a language of my very own for such personal views and acts of daring, la- bouring instead to express strange and new evaluations in Schopenhauerian and Kantian formulations, things which fundamentally ran counter to both the spirit and taste of Kant and Schopenhauer. -

How Sports Help to Elect Presidents, Run Campaigns and Promote Wars."

Abstract: Daniel Matamala In this thesis for his Master of Arts in Journalism from Columbia University, Chilean journalist Daniel Matamala explores the relationship between sports and politics, looking at what voters' favorite sports can tell us about their political leanings and how "POWER GAMES: How this can be and is used to great eect in election campaigns. He nds that -unlike soccer in Europe or Latin America which cuts across all social barriers- sports in the sports help to elect United States can be divided into "red" and "blue". During wartime or when a nation is under attack, sports can also be a powerful weapon Presidents, run campaigns for fuelling the patriotism that binds a nation together. And it can change the course of history. and promote wars." In a key part of his thesis, Matamala describes how a small investment in a struggling baseball team helped propel George W. Bush -then also with a struggling career- to the presidency of the United States. Politics and sports are, in other words, closely entwined, and often very powerfully so. Submitted in partial fulllment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 DANIEL MATAMALA "POWER GAMES: How sports help to elect Presidents, run campaigns and promote wars." Submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 Published by Columbia Global Centers | Latin America (Santiago) Santiago de Chile, August 2014 POWER GAMES: HOW SPORTS HELP TO ELECT PRESIDENTS, RUN CAMPAIGNS AND PROMOTE WARS INDEX INTRODUCTION. PLAYING POLITICS 3 CHAPTER 1. -

Ongon : a Tale of Early Chicago (1902) Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ONGON : A TALE OF EARLY CHICAGO (1902) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK DuBois Henry Loux | 196 pages | 31 Oct 2008 | Kessinger Publishing | 9781437072235 | English | Whitefish MT, United States Ongon : A Tale Of Early Chicago (1902) PDF Book But for Ongon, looking at the painting, they had shuddered before it under the sense of impending doom. Artist and model were in complete sympathy with the spur of her words chosen with quick discernment of his thoughts. Hoping to gain their trust, Craig burns through his department allowance and his own funds playing at a Fuxi card game. Afterpay offers simple payment plans for online shoppers, instantly at checkout. Owing to technicalities Joseph is left dangling for almost a year. He felt the reward of the virtuous was with him, for he could make his way where there were no dry leaves to crackle almost direct into the sunny opening. When Minnesota territory opened for settlement he moved to St. Then, keepmg to the sand of the shore for his route, his pouches flying out Hke wings from the sides of his steed, the Httle Frenchman galloped past, hastening on to Chicago with the weekly mail from the East. Illinois novels, books set in Illinois, books based in Illinois. And they would sing together, leaning to pray. Chicago: McClurg. Josie had caught her spirit, too, and the lines of their supple figures against the morning background of flowers and passing trees charmed him into his first entrance to the sweetest of all feelings — that every created form is man's to ap- preciate and enjoy. -

Unsettling the White Noise: Deconstructing the Nation-Building

Unsettling the White Noise: Deconstructing the Nation-Building Project of CBC Radio One’s Canada Reads By Emily M. Burns A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in the Department of Gender Studies in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada August, 2012 Copyright @ Emily M. Burns, 2012 Abstract The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s Canada Reads program, based on the popular television show Survivor, welcomes five Canadian personalities to defend one Canadian book, per year, that they believe all Canadians should read. The program signifies a common discourse in Canada as a nation-state regarding its own lack of coherent and fixed identity, and can be understood as a nationalist project. I am working with Canada Reads as an existing archive, utilizing materials as both individual and interconnected entities in a larger and ongoing process of cultural production – and it is important to note that it is impossible to separate cultural production from cultural consumption. Each year offers a different set of insights that can be consumed in their own right, which is why this project is written in the present tense. Focusing on the first ten years of the Canada Reads competition, I argue that Canada Reads plays a specific and calculated role in the CBC’s goal of nation-building: one that obfuscates repressive national histories and legacies and instead promotes the transformative powers of literacy as that which can conquer historical and contemporary inequalities of all types. This research lays bare the imagined and idealized ‘communities’ of Canada Reads audiences that the CBC wishes to reflect in its programming, and complicates this construction as one that abdicates contemporary responsibilities of settlers. -

VFA Programme 2020

Victoria Festival of Authors 2020 Dear Reader, The world was a very different place when we invited the authors you’ll listen to this week. It was possible, then, to imagine these writers together, reading and discussing their work only feet away from a live audience, rather than through their computer screens. And yet, though the world has changed, the relevance of this year’s offerings has only increased. The authors in our panel Simply Unbelievable: Fresh Fiction for Unfathomable Times all, as moderator Matthew J. Trafford states, “bravely contend with the contemporary crisis of credibility.” Together they will discuss how beliefs— about ourselves and about the systems of power we live within—can have direct and dire consequences on the way the world moves. The panelWriting in a Time of Slow Disaster brings together four authors who, through a variety of approaches and topics, are exploring what it means to be working in our present time of social upheaval and global climate disaster. Guest curator K.P Dennis’s panelQueer Existence is Resistance will explore the power and importance of QT2BIPOC futurisms in shaping and reframing the world we currently inhabit. Other offerings include three powerful voices writing for teens and tweens inBetween Worlds. In Truth, Trauma, Beauty, Beast, authors whose works in essay, poetry, and narrative freshly inhabit the world of memoir wrestle the truth in their stories in pursuit of a reconciling witness. For this year’sIn Conversation offering, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, who author Billy-Ray Belcourt describes as a “historian for our future”, will discuss her book Noopiming with artist Carey Newman.