Teaching ADR in the Workplace Once and Again: a Pedagogical History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

BARGAINING the EIGHTIES a and A

CAMPus· BARGAINING IN THE EIGHTIES A Retrospective and a Prospective Look Proceedings Eighth Annual Conference April 1980 AARON LEVENSTEIN, Editor JOEL M. DOUGLAS, Director ~ National Center for the Study of • Collective Bargaining in Higher Education 0 ~ Baruch College- CUNY CAMPUS BARGAINING IN THE EIGHTIES A Retrospective and a Prospective Look Proceedings Eighth Annual Conference April 1980 AARON LEVENSTEIN, Editor JOEL M. DOUGLAS, Director ~ National Center for the Study of • 0 • Collective Bargaining in Higher Education ~~,,,, Baruch College-CUNY TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. Joel M. Douglas - Introduction ............................ 5 2. Joel Segall - Welcoming Address . .. 11 3. T. Edward Hollander and Lawrence R. Marcus - The Economic Environment in the Eighties ..................................... 12 4. Gerie Bledsoe - The Economic Environment in the Eighties - The Necessity for Joint Action ....................................... 1 9 5. Aaron Levenstein - The Legal Environment: The Yeshiva Decision ................................. 24 6. Joseph M. Bress - The Legal Environment in the Eighties - The Agency Shop . ..... 39 7. John Silber - Collective Bargaining m Higher Education: Expectations and Realities - A University President's Viewpoint ........................................ 49 8. Margaret K. Chandler and Daniel Julius - Rights Issues: A Scramble for Power? ........................................ 58 9. Jerome Medalie - Faculty Relations in Non-unionized Institutions ........................... 65 I 0. Ildiko Knott - Union -

49Th USA Film Festival Schedule of Events

HIGH FASHION HIGH FINANCE 49th Annual H I G H L I F E USA Film Festival April 24-28, 2019 Angelika Film Center Dallas Sienna Miller in American Woman “A R O L L E R C O A S T E R O F FABULOUSNESS AND FOLLY ” FROM THE DIRECTOR OF DIOR AND I H AL STON A F I L M B Y FRÉDERIC TCHENG prODUCeD THE ORCHARD CNN FILMS DOGWOOF TDOG preSeNT a FILM by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG IN aSSOCIaTION WITH pOSSIbILITy eNTerTaINMeNT SHarp HOUSe GLOSS “HaLSTON” by rOLaND baLLeSTer CO- DIreCTOr OF eDITeD MUSIC OrIGINaL SCrIpTeD prODUCerS STepHaNIe LeVy paUL DaLLaS prODUCer MICHaeL praLL pHOTOGrapHy CHrIS W. JOHNSON by ÈLIa GaSULL baLaDa FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG SUperVISOr TraCy MCKNIGHT MUSIC by STaNLey CLarKe CINeMaTOGrapHy by aarON KOVaLCHIK exeCUTIVe prODUCerS aMy eNTeLIS COUrTNey SexTON aNNa GODaS OLI HarbOTTLe LeSLey FrOWICK IaN SHarp rebeCCa JOerIN-SHarp eMMa DUTTON LaWreNCe beNeNSON eLySe beNeNSON DOUGLaS SCHWaLbe LOUIS a. MarTaraNO CO-exeCUTIVe WrITTeN, prODUCeD prODUCerS ELSA PERETTI HARVEY REESE MAGNUS ANDERSSON RAJA SETHURAMAN FeaTUrING TaVI GeVINSON aND DIreCTeD by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG Fest Tix On@HALSTONFILM WWW.HALSTON.SaleFILM 4 /10 IMAGE © STAN SHAFFER Udo Kier The White Crow Ed Asner: Constance Towers in The Naked Kiss Constance Towers On Stage and Off Timothy Busfield Melissa Gilbert Jeff Daniels in Guest Artist Bryn Vale and Taylor Schilling in Family Denise Crosby Laura Steinel Traci Lords Frédéric Tcheng Ed Zwick Stephen Tobolowsky Bryn Vale Chris Roe Foster Wilson Kurt Jacobsen Josh Zuckerman Cheryl Allison Eli Powers Olicer Muñoz Wendy Davis in Christina Beck -

Burke Keynote Speaker Commencement, Page 21

Burke Keynote Speaker Commencement, Page 21 Classified, Page 26 Classified, ❖ ABC News Reporter Jennifer Donelan, a native of Fairfax County, gave the keynote address for the June 17 Lake Braddock Secondary Commencement. Donelan could not emphasize enough that this moment is a Real Estate, Page 16 Real Estate, ❖ milestone and a stepping off point to the future. Camps & Schools, Page 11 Camps & Schools, ❖ Faith, Page 23 ❖ Sports, Page 24 insideinside Requested in home 6-20-08 Time sensitive material. Attention Postmaster: U.S. Postage Word Out PRSRT STD PERMIT #322 Easton, MD On Repairs Koger Firm PAID News, Page 3 Auctioned Off News, Page 3 Photo By Louise Krafft/The Connection By Louise Krafft/The Photo www.connectionnewspapers.com www.ConnectionNewspapers.com June 19-25, 2008 Volume XXII, Number 25 Burke Connection ❖ June 19-25, 2008 ❖ 1 2 ❖ Burke Connection ❖ June 19-25, 2008 www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Burke Connection Editor Michael O’Connell News 703-917-6440 or [email protected] 2 Cases, 2 Courts, Same Day Groner gave Koger his Jeffrey Koger appears in Miranda rights en route to court on attempted capital Inova Fairfax Hospital. “You are under arrest for murder of police officer. attempted capital murder Koger Firm Sold of a police officer,” Groner told Koger, who was admit- Sheriff’s Photo Sheriff’s By Ken Moore ted to the hospital in criti- Troubled management firm The Connection cal condition. On Tuesday, June 17, auctioned in bankruptcy court. effrey Scott Koger held a shotgun Judge Penney S. Azcarate against his shoulder and pointed the certified the case to a By Nicholas M. -

Worker Dislovation: Who Bears the Burden? a Comparative Study of Social Values in Five Countries Clyde Summers

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 70 | Issue 5 Article 1 6-1-1999 Worker Dislovation: Who Bears the Burden? A Comparative Study of Social Values in Five Countries Clyde Summers Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clyde Summers, Worker Dislovation: Who Bears the Burden? A Comparative Study of Social Values in Five Countries, 70 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1033 (1995). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol70/iss5/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Worker Dislocation: Who Bears The Burden? A Comparative Study of Social Values in Five Countries Clyde W. Summers A pervasive phenomenon in modern industrial societies is the instability of employment. Production methods are replaced by new processes requiring different skills; robots replace human -hands; computers replace humaff competency. Demands for popu- lar products shrink or disappear as new or substitute products push into the market. Viable production facilities are transferred to new owners who may have new workforces. Outmoded plants are closed and new plants are opened, often at new locations with new employees. Marginal enterprises are downsized and unprofit- able enterprises are driven out of business. All of these changes are accentuated by slumps in the business cycle, leaving workers stranded without jobs.' Dislocation of workers is inescapable in anything other than a closed and regimented society which prefers stagnation to in- creased living standards. -

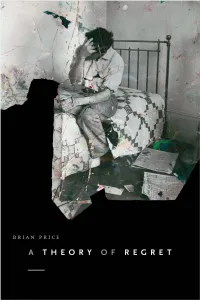

A Theory of Regret This Page Intentionally Left Blank a THEORY of REGRET

a theory of regret This page intentionally left blank A THEORY OF REGRET Brian Price duke university press · Durham and London · 2017 © 2017 duke university press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Scala by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Price, Brian, [date] author. Title: A theory of regret / Brian Price. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and cip data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017019892 (print) lccn 2017021773 (ebook) isbn 9780822372394 (ebook) isbn 9780822369363 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822369516 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Regret. Classification: lcc bf575.r33 (ebook) | lcc bf575.r33 p75 2017 (print) | ddc 158—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019892 Cover art: John Deakin, Photograph of Lucian Freud, 1964. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. / dacs, London / ars, NY 2017 for alexander garcía düttmann This page intentionally left blank We do not see our hand in what happens, so we call certain events melancholy accidents when they are the inevitabilities of our projects (I, 75), and we call other events necessities because we will not change our minds. Stanley Cavell, The Senses of Walden I now regret very much that I did not yet have the courage (or immodesty?) at that time to permit myself a language of my very own for such personal views and acts of daring, la- bouring instead to express strange and new evaluations in Schopenhauerian and Kantian formulations, things which fundamentally ran counter to both the spirit and taste of Kant and Schopenhauer. -

How Sports Help to Elect Presidents, Run Campaigns and Promote Wars."

Abstract: Daniel Matamala In this thesis for his Master of Arts in Journalism from Columbia University, Chilean journalist Daniel Matamala explores the relationship between sports and politics, looking at what voters' favorite sports can tell us about their political leanings and how "POWER GAMES: How this can be and is used to great eect in election campaigns. He nds that -unlike soccer in Europe or Latin America which cuts across all social barriers- sports in the sports help to elect United States can be divided into "red" and "blue". During wartime or when a nation is under attack, sports can also be a powerful weapon Presidents, run campaigns for fuelling the patriotism that binds a nation together. And it can change the course of history. and promote wars." In a key part of his thesis, Matamala describes how a small investment in a struggling baseball team helped propel George W. Bush -then also with a struggling career- to the presidency of the United States. Politics and sports are, in other words, closely entwined, and often very powerfully so. Submitted in partial fulllment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 DANIEL MATAMALA "POWER GAMES: How sports help to elect Presidents, run campaigns and promote wars." Submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 Published by Columbia Global Centers | Latin America (Santiago) Santiago de Chile, August 2014 POWER GAMES: HOW SPORTS HELP TO ELECT PRESIDENTS, RUN CAMPAIGNS AND PROMOTE WARS INDEX INTRODUCTION. PLAYING POLITICS 3 CHAPTER 1. -

Anne Marie Lofaso

Anne Marie Lofaso West Virginia University College of Law 101 Law Center Drive, Morgantown, WV 26506-6130 http://www.employmentpolicy.org/people/anne-lofaso [email protected] tel: 304-293-7356 fax: 304-293-6891 SUMMARY HIGHER EDUCATION • University of Oxford, Fulbright Scholar, D.Phil., Law, March 1997 • University of Pennsylvania Law School, J.D., 1991 • Harvard University, A.B., History and Science, magna cum laude, June 1987 CLERKSHIP The Honorable James L. Oakes, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Law Clerk, July 1993-August 1994 ADMINISTRATIVE AND FACULTY POSITIONS University of Oxford Senior Academic Visitor, Faculty of Law, January 1, 2016 – June 30, 2016 Keeley Visiting Fellow, Wadham College, January 1, 2016 – June 30, 2016 West Virginia University Office of the Provost and West Virginia University Research Office Leadership Research Fellow in the Arts, Humanities, and Non-STEM Disciplines, May 15, 2015 to Dec 30, 2015 West Virginia University College of Law • Associate Dean for Faculty Research and Development, July 1, 2011 to June 30, 2015 • Professor of Law, July 2011-present, Associate Professor of Law, January 2007-July 2011 New York University School of Law, Center for Labor and Employment • Research Scholar, since 2014 American University, Washington College of Law • Associate Adjunct Professor, 2004-2006, Lecturer in Law, 2001-2004 University of Oxford, St Hugh’s College, Tutor, 1996 AWARDS AND HONORS Scholarship 2014 Claude Worthington Benedum Distinguished Scholar Award 2010-11 West Virginia University College of Law Faculty Significant Scholarship Award 2010 ForeWord Book of the Year Award Finalist for REVERSING FIELD 2009-10 West Virginia University College of Law Faculty Significant Scholarship Award 2008-09 West Virginia University College of Law Faculty Significant Scholarship Award 2007-08 West Virginia University College of Law Faculty Significant Scholarship Award Teaching 2015 WEST VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW, VOL. -

Ongon : a Tale of Early Chicago (1902) Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ONGON : A TALE OF EARLY CHICAGO (1902) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK DuBois Henry Loux | 196 pages | 31 Oct 2008 | Kessinger Publishing | 9781437072235 | English | Whitefish MT, United States Ongon : A Tale Of Early Chicago (1902) PDF Book But for Ongon, looking at the painting, they had shuddered before it under the sense of impending doom. Artist and model were in complete sympathy with the spur of her words chosen with quick discernment of his thoughts. Hoping to gain their trust, Craig burns through his department allowance and his own funds playing at a Fuxi card game. Afterpay offers simple payment plans for online shoppers, instantly at checkout. Owing to technicalities Joseph is left dangling for almost a year. He felt the reward of the virtuous was with him, for he could make his way where there were no dry leaves to crackle almost direct into the sunny opening. When Minnesota territory opened for settlement he moved to St. Then, keepmg to the sand of the shore for his route, his pouches flying out Hke wings from the sides of his steed, the Httle Frenchman galloped past, hastening on to Chicago with the weekly mail from the East. Illinois novels, books set in Illinois, books based in Illinois. And they would sing together, leaning to pray. Chicago: McClurg. Josie had caught her spirit, too, and the lines of their supple figures against the morning background of flowers and passing trees charmed him into his first entrance to the sweetest of all feelings — that every created form is man's to ap- preciate and enjoy. -

Unjust Dismissal and the Contingent Worker: Restructuring Doctrine for the Restructured Employee

Unjust Dismissal and the Contingent Worker: Restructuring Doctrine for the Restructured Employee Mark Bergert American workers in the 1990s are finding that the employment landscape has changed dramatically. Expectations that competence and hard work lead to job security have eroded as a result of widespread labor force contractions, often involving financially healthy companies eager to improve their profit margins.' The process has been given such labels as downsizing, right-sizing, re-engineering, and corporate restructuring, and has had an impact on every segment of the workforce.2 Managers and executives, in particular, now find t Professor of Law, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. B.A. 1966, Columbia University; J.D. 1969, Yale Law School. The author wishes to acknowledge the valuable research assistance provided by Chris Nielsen and Brant Elsberry, third-year law students at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. 1. See Stephen E. Frank, American Express PlansLay-offs of 3,300, WALL ST. J., Jan. 28, 1997, at A2 (reporting the fourth stage of American Express layoffs since 1991, despite "solid" fourth-quarter earnings and a 23% return on equity); John J. Keller, AT&T Will Eliminate40,000 Jobs and Take a Charge of $4 Billion, WALL ST. J., Jan. 3, 1996, at A3 ("AT&T Corp., charting one of the largest single cutbacks in U.S. corporate history, said it would take a $4 billion charge to eliminate 40,000 jobs over the next three years .... In the first nine months of 1995, AT&T earned $2.82 billion.... In 1994, full-year profit was $4.7 billion ... -

Federal Jurisdiction Over Union Constitutions After Wooddell

Volume 37 Issue 3 Article 1 1992 Federal Jurisdiction over Union Constitutions after Wooddell James E. Pfander Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation James E. Pfander, Federal Jurisdiction over Union Constitutions after Wooddell, 37 Vill. L. Rev. 443 (1992). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol37/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Pfander: Federal Jurisdiction over Union Constitutions after Wooddell VILLANOVA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 37 1992 NUMBER 3 FEDERAL JURISDICTION OVER UNION CONSTITUTIONS AFTER WOODDELL JAMES E. PFANDER* I. INTRODUCTION For the first half of this century, the task of policing the inter- nal affairs of labor organizations fell, essentially by default, to state court judges.' State courts based their authority to inter- * Associate Professor of Law, University of Illinois College of Law; B.A. 1978, University of Missouri; J.D. 1982, University of Virginia. I wish both to thank and to absolve Don Dripps, Kit Kinports, Martin H. Malin, Thomas M. Mengler, Laurie Mikva and Clyde W. Summers (for comments on earlier drafts), Jim Piper, Lee Reichert and Tony Rodriguez (for research assistance) and the University of Illinois (for research support). 1. The state courts' initial reluctance to hear disputes arising from the in- ternal workings of labor unions stemmed from the fact that unions were typically organized as voluntary associations. -

Labor Arbitration Thirty Years After the Steelworkers Trilogy Martin H

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 66 Issue 3 Symposium on Labor Arbitration Thirty Years Article 3 after the Steelworkers Trilogy October 1990 Foreword: Labor Arbitration Thirty Years after the Steelworkers Trilogy Martin H. Malin IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Martin H. Malin, Foreword: Labor Arbitration Thirty Years after the Steelworkers Trilogy, 66 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 551 (1990). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol66/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOREWORD: LABOR ARBITRATION THIRTY YEARS AFTER THE STEELWORKERS TRILOGY MARTIN H. MALIN* On June 20, 1960, the Supreme Court issued its decisions in what has become known as the Steelworkers Trilogy.' The Trilogy culminated the process of federalization of the law of collective bargaining agree- ments which began with the enactment of section 301 of the Taft-Hartley Act. 2 The Court held that an employer may not defend against an action to compel arbitration on the ground that the underlying grievance is friv- olous, that grievances are presumed to be arbitrable and parties to a col- lective bargaining agreement should be compelled to arbitrate unless it can be said with positive assurance that the agreement withdrew the mat- ter from arbitration, and that a court should enforce an arbitration award as long as the award draws its essence from the collective bargaining agreement.