Carbon–Forestry Projects in the Philippines: Potential and Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[ Republic Act No. 9 4 0 2 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8971/republic-act-no-9-4-0-2-358971.webp)

[ Republic Act No. 9 4 0 2 ]

H. No. 5953 -I- Begun and held in Metro Manila, on Monday, the twenty-fourth day of July. two thousand six. [ REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9 4 0 2 ] AN ACT CONVERTING TKE LAGUNA STATE POLYTECHNIC COLLEGE IN THE PROVINCE OF LAGUNA INTO A STATE UNIVERSITY TO BE KNOWN AS THE LAGUNA STATE POLYTECHNIC UNIVERSITY AND APPROPRIATING FUNDS THEREFOR Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Philippines in Congress assembled: SECTION1. Conversion. -The Laguna State Polytechnic College (LSPC) in the Province of Laguna, which is composed of the LSPC Siniloan Campus in the Municipality of Siniloan, the LSPC Sta. Cruz Campus in the Municipality of Sta. Cruz, the LSPC Los Bafios Campus in the Municipality of Los Baiios and the LSPC San Pablo City Campus in the City of San Pablo, and the satellite campuses located in the municipalities of Cabuyao, Nagcarlan and Sta. Cruz Sports Complex, is hereby converted into a state university to be known as the Laguna 2 State Polytechnic University, hereinafter referred to as the University. The main campus of the University shall be in Sta. Cruz, Laguna. SEC. 2. General Mandate. -The University shall primarily provide advanced education, professional, technological and vocational instruction in agriculture, fisheries, forestry, science, engineering, industrial technologies, teacher education, medicine, law, arts and sciences, information technology and other related fields. It shall also undertake research and extension services, and provide progressive leadership in its areas of specialization. SEC. 3. Curricular Offerings.-The University shall offer graduate, undergraduate, and short-term technical courses within its areas of specialization and according to its capabilities, as the Board of Regents may deem necessary to carry out its objectives and in order to meet the needs of the Province of Laguna and Region IV-A. -

Laguna Lake Development and Management

LAGUNA LAKE DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY Presentation for The Bi-Lateral Meeting with the Ministry of Environment Japan On LAGUNA DE BAY Laguna Lake Development Authority Programs, Projects and Initiatives Presented By: CESAR R. QUINTOS Division Chief III, Planning and Project Development Division October 23, 2007 LLDA Conference Room Basic Fac ts o n Lagu na de Bay “The Lake of Bay” Laguna de Bay . The largest and most vital inland water body in t he Philipp ines. 18th Member of the World’s Living Lakes Network. QUICK FACTS Surface Area: * 900 km2 Average Depth: ~ 2.5 m Maximum Depth: ~ 20m (Diablo Pass) AerageVolmeAverage Volume: 2,250,000,000 m3 Watershed Area: * 2,920 km2 Shoreline: * 285 km Biological Resources: fish, mollusks, plankton macrophytes (* At 10.5m Lake Elevation) The lake is life support system Lakeshore cities/municipalities = 29 to about 13 million people Non-lakeshore cities/municipalities= 32 Total no. of barangays = 2,656 3.5 million of whom live in 29 lakeshore municipalities and cities NAPINDAN CHANNEL Only Outlet Pasig River connects the lake to Manila Bay Sources of surface recharge 21 Major Tributaries 14% Pagsanjan-Lumban River 7% Sta. Cruz River 79% 19 remaining tributary rivers The Pasig River is an important component of the lake ecosystem. It is the only outlet of the lake but serves also as an inlet whenever the lake level is lower than Manila Bay. Salinity Intrusion Multiple Use Resource Fishing Transport Flood Water Route Industrial Reservoir Cooling Irrigation Hydro power generation Recreation Economic Benefits -

Pattern of Investment Allocation to Chemical Inputs and Technical Efficiency: a Stochastic Frontier Analysis of Farm Households in Laguna, Philippines

Pattern of investment allocation to chemical inputs and technical efficiency: A stochastic frontier analysis of farm households in Laguna, Philippines Orlee Velarde and Valerien Pede International Rice Research Institute Laguna, Philippines 4030 Selected paper prepared for presentation at the 57th AARES Annual Conference, Sydney, New South Wales, 5th-8th February, 2013 Pattern of investment allocation to chemical inputs and technical efficiency: A stochastic frontier analysis of farm households in Laguna, Philippines † Orlee Velarde †and Valerien Pede International Rice Research Institute Abstract This study focuses on the pattern between investment in chemical inputs such as fertilizer, pesticides and herbicides and technical efficiency of farm households in Laguna, Philippines. Using a one‐stage maximum likelihood estimation procedure, the stochastic production frontier model was estimated simultaneously with the determinants of efficiency. Results show that farmers with a low technical efficiency score have a high investment share in chemical inputs. Farmers who invested more in chemical inputs relative to other variable inputs attained the same or even lower output and were less efficient than those farmers who invested less. The result shows that farmers who invested wisely in chemical inputs can encourage farmers to apply chemical inputs more optimally. Keywords: Agricultural Management, Agricultural Productivity, Farm Household, Fertilizer Use, Rice JEL Classification Q12 – Micro‐Analysis of Farm Firms, Farm Households, and Farm Input Markets © Copyright 2013 by Orlee Velarde and Valerien Pede. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non‐commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. † Corresponding author Email: [email protected] 2 | Page 1. -

DA-NFA Laguna Continues to Buy Palay Directly from Farmers Amid COVID-19

DA-NFA Laguna continues to buy palay directly from farmers amid COVID-19 Farmers and farmers’ groups went to the Department of Agriculture – National Food Authority (DA-NFA) Buying Station in Siniloan, Laguna on April 14, 2020, to sell their dry and clean palay at a fair price (see photos). According to Provincial Manager Roman M. Sanchez, the DA-NFA Laguna continues to procure palay from farmers to help ensure that their precious produce will not go to waste and that there is sufficient buffer stock for the consumers, especially during this time of crisis. "We have six buying stations or warehouses in Laguna – three in San Pablo City, and one each in Calauan, Siniloan, and Pagsanjan wherein farmers can sell their palay at nineteen pesos per kilogram. We have personnel manning each buying station or warehouse to accommodate walk-in farmers who would like to sell their palay," Mr. Sanchez said. He added that to date, they have procured a total of 2,024 bags of palay directly from farmers for this year and they will continue to do so as they are intensifying their information dissemination with the help of DA Regional Field Office No. IV-CALABARZON, National Irrigation Administration Region IV-A, and local government units to encourage more farmers to sell their produce to them. Regional Director Arnel V. de Mesa commended the efforts of NFA Laguna in serving as a viable market for rice farmers and emphasized that this is the time when the government agencies like DA, NFA, and other attached agencies and bureaus must really be felt by the farmers – that they are not alone in their fight to ensure food sufficiency. -

2015Suspension 2008Registere

LIST OF SEC REGISTERED CORPORATIONS FY 2008 WHICH FAILED TO SUBMIT FS AND GIS FOR PERIOD 2009 TO 2013 Date SEC Number Company Name Registered 1 CN200808877 "CASTLESPRING ELDERLY & SENIOR CITIZEN ASSOCIATION (CESCA)," INC. 06/11/2008 2 CS200719335 "GO" GENERICS SUPERDRUG INC. 01/30/2008 3 CS200802980 "JUST US" INDUSTRIAL & CONSTRUCTION SERVICES INC. 02/28/2008 4 CN200812088 "KABAGANG" NI DOC LOUIE CHUA INC. 08/05/2008 5 CN200803880 #1-PROBINSYANG MAUNLAD SANDIGAN NG BAYAN (#1-PRO-MASA NG 03/12/2008 6 CN200831927 (CEAG) CARCAR EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE GROUP RESCUE UNIT, INC. 12/10/2008 CN200830435 (D'EXTRA TOURS) DO EXCEL XENOS TEAM RIDERS ASSOCIATION AND TRACK 11/11/2008 7 OVER UNITED ROADS OR SEAS INC. 8 CN200804630 (MAZBDA) MARAGONDONZAPOTE BUS DRIVERS ASSN. INC. 03/28/2008 9 CN200813013 *CASTULE URBAN POOR ASSOCIATION INC. 08/28/2008 10 CS200830445 1 MORE ENTERTAINMENT INC. 11/12/2008 11 CN200811216 1 TULONG AT AGAPAY SA KABATAAN INC. 07/17/2008 12 CN200815933 1004 SHALOM METHODIST CHURCH, INC. 10/10/2008 13 CS200804199 1129 GOLDEN BRIDGE INTL INC. 03/19/2008 14 CS200809641 12-STAR REALTY DEVELOPMENT CORP. 06/24/2008 15 CS200828395 138 YE SEN FA INC. 07/07/2008 16 CN200801915 13TH CLUB OF ANTIPOLO INC. 02/11/2008 17 CS200818390 1415 GROUP, INC. 11/25/2008 18 CN200805092 15 LUCKY STARS OFW ASSOCIATION INC. 04/04/2008 19 CS200807505 153 METALS & MINING CORP. 05/19/2008 20 CS200828236 168 CREDIT CORPORATION 06/05/2008 21 CS200812630 168 MEGASAVE TRADING CORP. 08/14/2008 22 CS200819056 168 TAXI CORP. -

Local Franchise

Republic of the Philippines ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION San Miguel Avenue, Pasig City IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION FOR AUTHORITY TO INCLUDE IN CUSTOMER'S BILL A TAX RECOVERY ADJUSTMENT CLAUSE (TRAC) FOR FRANCHISE TAXES PAID IN THE PROVINCE OF LAGUNA AND BUSINESS TAX PAID IN THE MUNICIPALITIES OF PANGIL, LUMBAN,PAGSANJAN AND PAKIL ALL IN THE PROVINCE OF LAGUNA ERC CASE NO. 2013-002 CF FIRST ,LAGUNA ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC. (FLECO), Applicant. x- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - x DECISION Before this Commission for resolution is the application filed on January 8, 2013 by the First Laguna Electric Cooperative, Inc, (FLECO) for authority to include in its customer's bill a Tax Recovery Adjustment Clause (TRAC) for franchise taxes paid to the Province of Laguna and business taxes paid to the Municipalities of Pangil, Lumban, Pagsanjan and Pakil, all in the Province of Laguna. In the said application, FLECO alleged, among others, that: 1. It is a non-stock non-profit electric cooperative (EC) duly organized and existing under and by virtue of the laws of the Republic of the Philippines. It is represented by its Board President, Mr. Gabriel C. Adefuin, It has its principal office at Barangay Lewin, Lumban, Laguna; " ERC CASE NO. 2013-002 CF DECISION/April 28, 2014 Page 2 of 18 2. It is the exclusive holder of a franchise issued by the National Electrification Administration (NEA) to operate an electric light and power services in the Municipalities of Cavinti, Pagsanjan, Lumban, Kalayaan, Paete, Pakil, Pangil, Siniloan, Famy, Mabitac, and Sta. Maria, all in the Province of Laguna; 3. -

SEPTEMBER 20 15 Ddiissttrriicctt Ddeeppuuttyy

SEPTEMBER 20 15 DDiissttrriicctt DDeeppuuttyy KNIGHTS OF COLUMBUS - 1 COLUMBUS PLAZRA, NeEWm HAViEnN, dCONeNEr CTICUT IMPORTANT REMINDERS CAMPAIGN FOR PEOPLE WITH • Encourage each council in your district to utilize INTELLECTUAL DISABILITIES the Member Management/Member Billing ne of the most popular and successful Applications located in Officers Online. programs conducted by local councils • Supreme Council Office staff is here to assist benefits people with intellectual disabilities you by keeping you informed about Orderwide Oby collecting funds outside stores and on street news, council reminders and membership corners. In appreciation, the donor is offered a piece initiatives. Should you have any questions or of candy, often a Tootsie Roll ®. The high visibility of comments during your term as district deputy, this program has led to the campaign being referred please send an e-mail to [email protected]. to as the “Tootsie Roll Drive.” • Ensure that councils submitted the Semiannual Council Audit (#1295). Submission is required While the nickname is understandable, it is to retain bonding on the offices of the financial misleading since the Knights of Columbus has no secretary and treasurer. official tie to Tootsie Rolls or their manufacturer. NEW MEMBERSHIP Many councils participate in the same fundraising RECRUITMENT VIDEO drive, but distribute other items. References to this During the Membership 365 Seminar held at the program should highlight the positive aspects of the 2015 Supreme Convention, the supreme knight fundraising and not advertise candy. If councils in introduced a new membership your district conduct this program, it is recommended recruitment video — An that it be promoted as the “Campaign for People with Invitation . -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Volume 2. Manggahan Sub-basin ............................................................................ 3 Geographic Location .......................................................................................................... 3 Political and Administrative Boundary ................................................................................. 4 Land Cover ......................................................................................................................... 6 Sub-basin Characterization and Properties......................................................................... 8 Drainage Network ........................................................................................................... 8 Sub-sub basin Properties ................................................................................................ 8 Water Quantity ................................................................................................................. 10 Stream flow ................................................................................................................... 10 Water Balance .............................................................................................................. 10 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 2-1 Geographical Map .......................................................................................................... 3 Figure 2-2 Political Map ................................................................................................................... -

ISSN: 2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 7(10), 870-877

ISSN: 2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 7(10), 870-877 Journal Homepage: - www.journalijar.com Article DOI: 10.21474/IJAR01/9902 DOI URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/9902 RESEARCH ARTICLE DEMAND AND SUPPLY ANALYSIS OF CAKES MADE OF FRUIT IN THE EASTERN PART OF LAGUNA: A BENCHMARK STUDY FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF CAKE BUSINESS IN SINILOAN LAGUNA. Juliet A. Caramonte, MBA College of Business Management and Accountancy, Laguna State Polytechnic University (LSPU)Siniloan, Laguna, Philippines. …………………………………………………………………………………………………….... Manuscript Info Abstract ……………………. ……………………………………………………………… Manuscript History A study was conducted in the four municipality in the Eastern part of Received: 14 August 2019 Laguna during summer of 2016. It aimed to seek an optimistic Final Accepted: 16 September 2019 opportunity on creating a unique cake products that could meet interest Published: October 2019 of the people who are looking for a new variety of taste for cakes made of fruit. Key words:- Demand and Supply, Innovation, Based on the survey there are a lot of bakeshop but there is none who Utilization, economic impact. produce cake products with cream filling. Utilization of raw materials such as fruits like ube, macapuno, langka and other fruit available during every season will be use as flavours for production of cake. Results showed that population as one of the demand determinants increased by 13.79% from 2010-2015 in Siniloan Laguna. The demand for cakes is increasing as population grows every year. Changes in one’s tastes and preferences was also the main concern of the study for the human satisfaction and consumption. Results revealed that Supply for cakes are only limited in the eastern part of Laguna based on survey. -

Presentation of Lennie Santos-Borja (3.4

RE-GREENING THE LAGUNA DE BAY WATERSHED: PARTNERSHIP THROUGH CDM AND N0N-CDM REFORESTATION PROJECTS Edgardo C. Manda General Manager and Lennie C. Santos-Borja Chief, Research and Development Division Head, Carbon Finance Unit Laguna Lake Development Authority, Philippines 12th Living Lakes Conference 25 September 2008 Castiglione del Lago, Regione Umbria Italy THE PHILIPPINE ARCHIPELAGO THE LAGUNA DE BAY BASIN 1 Laguna de Bay Features • Average Depth: ~2.5 m. • Average Volume: 2.25 MCM Mar ikina • Shoreline: 285 km. • Lake surface area: 900 km2 • Watershed area: ~2920 km2 Mang ahan Ba ras Mor on g Ta nay Ta guig • (24 sub-basins including many tributaries A ngon o Pililla St a. M aria + a floodway) Sin ilo an Pang il • 6 provinces, 12 cities, 49 municipalities Munt inlup a Jala -jala Sa n Pe dro • Of which 27 are lakeshore towns and 2 are Calir aya Biñan lakeshore cities Cab uyao Pa gsanja n Pila • One outlet: Napindan Channel – Pasig River San Cr ist oba l Los B año s (serves as inlet of saline water during C alauan St a. C ru z San Ju an Pasig River backflow) The Largest Lake in the Philippines and one of the largest in Southeast Asia 2 A THREATENED ECOSYSTEM Forests receded . 14% 5% 29% 52% Forest 19,100 has. Open 53,480 has Built- up/Industrial 110,780 has. Agricultural 198,640 has. Extensive built-up of agriculture areas. 3 4 sedimentation of the lake Delta formation 5 N TAYTAY ANGONO BINANGONAN PASIG CARDONA BARAS TAGUIG LUPANG ARENDA SUCAT TANAY PILILLA TAYTAY, RIZAL MUNTINLUPA SAN PEDRO SINILOAN BIÑAN MABITAC STA. -

2009 to 2012 Annual Water Quality Report on the Laguna De Bay and Its Tributary Rivers

2009 to 2012 Annual Water Quality Report on the Laguna de Bay and its Tributary Rivers Department Of Environment And Natural Resources LAGUNA LAKE DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY Sugar Regulatory Administration (SRA) Compound, North Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City FOREWORD This report contains the water quality data on Laguna de Bay (LdB) and its tributary rivers generated by the Environmental Laboratory and Research Division (ELRD) of LLDA, formerly Environmental Quality Management Division (EQMD), from 2009 to 2012 for the LLDA’s Water Quality Monitoring Program which has been on-going since 1973. The results of the assessment of the lake and its tributary rivers’ water quality status during the 4-year monitoring period based on compliance to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Class C Water Quality Criteria as prescribed under DENR Administrative Order (DAO) No.34, Series of 1990, are also presented. From 2009 to 2011, the five (5) stations monitored in Laguna de Bay were Station I (Central West Bay), Station II (East Bay), Station IV (Central Bay), Station V (Northern West Bay) and Station VIII (South Bay). By 2012, four (4) new monitoring stations were added, namely: Station XV (West Bay- San Pedro), Station XVI (West Bay- Sta Rosa), Station XVII (Central Bay- Fish Sanctuary) and Station XVIII (East Bay- Pagsanjan). For the monitoring of the Laguna de Bay’s tributaries, LLDA has a total of eighteen (18) stations in 2009 to 2010 that included Marikina, Bagumbayan, Mangangate, Tunasan (Downstream), San Pedro, Cabuyao, San Cristobal, San Juan, Bay, Sta. Cruz, Pagsanjan, Pangil (Downstream), Siniloan, Tanay (Downstream), Morong (Downstream) and Sapang Baho Rivers, Buli Creek, and Manggahan Floodway. -

Laguna De Bay Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

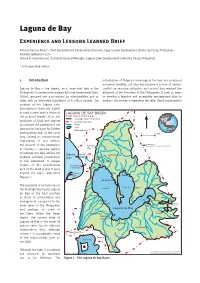

Laguna de Bay Experience and Lessons Learned Brief Adelina Santos-Borja*, Chief, Research and Development Division, Laguna Lake Development Authority, Pasig, Philippines, [email protected] Dolora N. Nepomuceno, Assistant General Manager, Laguna Lake Development Authority, Pasig, Philippines * Corresponding author 1. Introduction introduction of fi shpen technology in the lake has produced economic benefi ts, but also has become a source of serious Laguna de Bay is the largest, most important lake in the confl ict on resource utilization and access that reached the Philippines. Its watershed contains 66 Local Government Units attention of the President of the Philippines. It took 15 years (LGUs), grouped into 5 provinces, 49 municipalities and 12 to develop a feasible and acceptable management plan to cities with an estimated population of 6 million people. The address the concerns regarding the lake. Rapid urbanization creation of the Laguna Lake Development Authority (LLDA) in 1966 started with a vision of /$*81$'(%$<%$6,1 1 the political leaders from the 7+(3+,/,33,1(6 'UDLQDJH%DVLQ%RXQGDU\ provinces of Rizal and Laguna //'$-XULVGLFWLRQ to cultivate the potential of the 5LYHU lake and its environs for further /DNH 6HOHFWHG&LW\ development and, at the same NP time, control its environmental degradation. It also refl ects -XULVGLFWLRQRI the wisdom of the lawmakers 4XH]RQ /DJXQD/DNH'HYHORSPHQW$XWKRULW\ in creating a separate agency &LW\ 0DULNLQD5 to manage the lake amidst the 0DQLOD 0DQLOD $QWLSROR&LW\ multiple political jurisdictions %D\ 3DVLJ &LW\ in the watershed. A unique 7D\WD\ 5 3DVLJ5 J Q feature of the jurisdictional $UHDZLWKLQWKLV R U DUHDLVRXWVLGH R area of the LLDA is that it goes //'$MXULVGLFWLRQ 0 beyond the lake’s watershed &DYLWH 7DQD\ (Figure 1).