Protecting Groups Spring 2019 Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IV (Advance Organic Synthesis and Supramolecular Chemistry and Carbocyclic Rings) Module No and 9: Protection and Deprotection Title Module Tag CHE P14 M9

Subject Chemistry Paper No and Title 14: Organic Chemistry –IV (Advance Organic Synthesis and Supramolecular Chemistry and carbocyclic rings) Module No and 9: Protection and deprotection Title Module Tag CHE_P14_M9 CHEMISTRY Paper No. 14: Organic Chemistry –IV (Advance Organic Synthesis and Supramolecular Chemistry and carbocyclic rings) Module No. 9: Protection and deprotection Table of Content 1. Learning outcomes 2. Introduction 3. Protecting groups for carbonyl compounds 4. Protecting groups for alcohols 5. Protecting groups for amines 6. Summary CHEMISTRY Paper No. 14: Organic Chemistry –IV (Advance Organic Synthesis and Supramolecular Chemistry and carbocyclic rings) Module No. 9: Protection and deprotection 1. Learning Outcomes After studying this module, you shall be able to Know about protecting groups. Study the characteristics of protecting groups. Understand the functional group protection. Know the protection of important functional groups. 2. Introduction Protection and deprotection is an important part of organic synthesis. During the course of synthesis, we many times desire to perform reaction at only one of the two functional groups in any single organic molecules. For example, in an organic compound possessing two functional groups like ester and ketone, we have to perform reaction at only ester group, them the keto group needs to be protected. If we want to reduce the ester group, then keto group will also get reduced. To avoid this type of complications, protection and deprotection of functional groups are necessary. 3. Protecting groups for carbonyl compounds The protecting groups allow the masking of a particular functional group where a specified reaction is not to be performed. The protection is required as it interferes with another reaction. -

Chapter 3. the Concept of Protecting Functional Groups

Chapter 3. The Concept of Protecting Functional Groups When a chemical reaction is to be carried out selectively at one reactive site in a multifunctional compound, other reactive sites must be temporarily blocked. A protecting group must fulfill a number of requirements: • The protecting group reagent must react selectively (kinetic chemoselectivity) in good yield to give a protected substrate that is stable to the projected reactions. • The protecting group must be selectively removed in good yield by readily available reagents. • The protecting group should not have additional functionality that might provide additional sites of reaction. 3.1 Protecting of NH groups Primary and secondary amines are prone to oxidation, and N-H bonds undergo metallation on exposure to organolithium and Grignard reagents. Moreover, the amino group possesses a lone pair electrons, which can be protonated or reacted with electrophiles. To render the lone pair electrons less reactive, the amine can be converted into an amide via acylation. N-Benzylamine Useful for exposure to organometallic reagents or metal hydrides Hydrogenolysis Benzylamines are not cleaved by Lewis acid Pearlman’s catalyst Amides Basicity of nitrogen is reduced, making them less susceptible to attack by electrophilic reagent The group is stable to pH 1-14, nucleophiles, organometallics (except organolithium reagents), catalytic hydrogenation, and oxidation. Cleaved by strong acid (6N HCl, HBr) or diisobutylaluminum hydride Carbamates Behave like a amides, hence no longer act as nucleophile Stable to oxidizing agents and aqueous bases but may react with reducing agents. Iodotrimethylsilane is often the reagent for removal of this protecting group Stable to both aqueous acid and base Benzoyloxycarbonyl group for peptide synthesis t-butoxycarbonyl group(Boc) is inert to hydrogenolysis and resistant to bases and nucleophilic reagent. -

Photoremovable Protecting Groups

1348_C69.fm Page 1 Monday, October 13, 2003 3:22 PM 69 Photoremovable Protecting Groups 69.1 Introduction ..................................................................... 69-1 69.2 Historical Review.............................................................. 69-2 o-Nitrobenzyl • Benzoin • Phenacyl • Coumaryl and Arylmethyl 69.3 Carboxylic Acids............................................................. 69-17 o-Nitrobenzyl • Coumaryl • Phenacyl • Benzoin • Other Richard S. Givens 69.4 Phosphates and Phosphites ........................................... 69-23 o-Nitrobenzyl • Coumaryl • Phenacyl • Benzoin University of Kansas 69.5 Sulfates and Other Acids................................................ 69-26 Peter G. Conrad, II 69.6 Alcohols, Thiols, and N-Oxides .................................... 69-27 University of Kansas o-Nitrobenzyl • Thiopixyl and Coumaryl • Benzoin • Other Abraham L. Yousef 69.7 Phenols and Other Weak Acids..................................... 69-36 o-Nitrobenzyl • Benzoin University of Kansas 69.8 Amines ............................................................................ 69-37 Jong-Ill Lee o-Nitrobenzyl • Benzoin Derivatives • Arylsulfonamides University of Kansas 69.9 Conclusion...................................................................... 69-40 69.1 Introduction Photoremovable protecting groups are enjoying a resurgence of interest since their introduction by Kaplan1a and Engels1b in the late 1970s. A review of published work since 19932 is timely and will provide information about -

A Protecting Group Must Fulfill a Number of Requirements

Chapter 3. The Concept of Protecting Functional Groups When a chemical reaction is to be carried out selectively at one reactive site in a multifunctional compound, other reactive sites must be temporarily blocked. A protecting group must fulfill a number of requirements: • The protecting group reagent must react selectively (kinetic chemoselectivity) in good yield to give a protected substrate that is stable to the projected reactions. • The protecting group must be selectively removed in good yield by readily available reagents. • The protecting group should not have additional functionality that might provide additional sites of reaction. 1 3.1 Protecting of NH groups Primary and secondary amines are prone to oxidation, and N-H bonds undergo metallation on exposure to organolithium and Grignard reagents. Moreover, the amino group possesses a lone pair electrons, which can be protonated or reacted with electrophiles. To render the lone pair electrons less reactive, the amine can be converted into an amide via acylation. N-Benzylamine Useful for exposure to organometallic reagents or metal hydrides Hydrogenolysis Benzylamines are not cleaved by Lewis acid Pearlman’s catalyst 2 Amides Basicity of nitrogen is reduced, making them less susceptible to attack by electrophilic reagent The group is stable to pH 1-14, nucleophiles, organometallics (except organolithium reagents), catalytic hydrogenation, and oxidation. Cleaved by strong acid (6N HCl, HBr) or diisobutylaluminum hydride Carbamates Behave like a amides, hence no longer act as nucleophile Stable to oxidizing agents and aqueous bases but may react with reducing agents. Iodotrimethylsilane is often the reagent for removal of this protecting group Stable to both aqueous acid and base Benzoyloxycarbonyl group for peptide synthesis 3 t-butoxycarbonyl group(Boc) is inert to hydrogenolysis and resistant to bases and nucleophilic reagent. -

Deprotection Guide

Deprotection Guide 1 glenresearch.com Deprotect to Completion Contents Deprotect to Completion. 2 RNA Deprotection . 5 Dye-Containing Oligonucleotides . 8 Alternatives to Ammonium Hydroxide . 9 On-Column Deprotection of Oligonucleotides in Organic Solvents . 12 Introduction First, Do No Harm! This guide offers practical information that will help newcomers Determination of the appropriate deprotection scheme should to the field of oligo synthesis to understand the various start with a review of the components of the oligonucleotide to considerations before choosing the optimal deprotection determine if any group is sensitive to base and requires a mild strategy, as well as the variety of options that are available deprotection or if there are any pretreatment requirements. for deprotection. It is not the intent of this guide to provide Sensitive components are usually expensive components so it a comprehensive, fully referenced review of deprotection is imperative to follow the procedure we recommend for any strategies in oligonucleotide synthesis - they are simply individual component. For example, the presence of a dye like guidelines. For more detailed information, see, for example, TAMRA or HEX will require a different procedure from regular the review1 by Beaucage and Iyer. unmodified oligonucleotides. Similarly, an oligo containing a base-labile monomer like 5,6-dihydro-dT will have to be treated Oligo deprotection can be visualized in three parts: cleavage, according to the procedure that is noted on the product insert phosphate deprotection, and base deprotection. Cleavage (Analytical Report, Certificate of Analysis, or Technical Bulletin). is removal from the support. Phosphate deprotection is the Occasionally, some products require a special pretreatment to removal of the cyanoethyl protecting groups from the phosphate prevent unwanted side reactions. -

Protecting Groups (2Nd Edition), 1994, Georg Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, P

Protective Groups in Synthetic Organic Chemistry OTBS OPMB O Lecture Notes O Me Key Texts O Me XX P. J. Kocienski, Protecting Groups (2nd Edition), 1994, Georg Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, p. 260. P. J. Kocienski, Protecting Groups (3rd Edition), 2004, Georg Thieme: Stuttgart, p. 679. T. W. Greene, P. G. M. Wutz, Protective Groups in Organic Synthesis (3rd Edition), 1999, John Wiley and Sons: New York, p. 779. Key Reviews Selective Deprotections: T. D. Nelson, R. D. Crouch, Synthesis 1996, 1065. Protective Groups: Background and General Considerations "Protection is a principle, not an expedient" Benjamin Disraeli, British Prime Minister, 1845 "Like death and taxes, protecting groups have become a consecrated obstruction which we cannot elude" Peter Kocienski, Organic Chemist Remember: Every protecting group adds at least one, if not two steps to a synthesis They only detract from the overall efficiency and beauty of a route, but, without them, there are certainly transformations which we would not be able to do at all. Protective Groups: Temporary Protection Li Li O O N Li HO Ph Me O O O THF, -40 °C OLi aqueous O MeO O MeO work-up MeO N Ph Me Temporary protection involves the ideal for protecting groups when they are required: the protection step, desired reaction, and deprotection all occur in the same pot. Ene Reactions in Total Synthesis: Ene/Retro-Ene Sequence to Protect Indole O O H CO Me CH2Cl2, MeN H CO Me 2 O NH 2 0 °C, N NAc 1 min O N NAc NMe N N + NMe N N 150 °C, H O N 1 min N H Me Me O Me Me MTAD MTAD = N-methyltriazolinedione Me N MTAD, N OH Me Me N OH CH2Cl2, O MeH Me H 110 °C, MeH 0 °C, 1 h; N 30 min N N O H O O H 1 MeN NH H O2 H O (70% H O N N H O N (O2, O overall N methylene based on blue) r.s.m.) Retro N Ene N N H Me Me reaction Me Me Ene H Me Me reaction okaramine N P. -

Protecting Groups Are Attacked by the by Attacked Are Groups Protecting -Troc -Phthalimido), Benzylidene and Isopropyl- O N CO 2

View Online / Journal Homepage / Table of Contents for this issue REVIEW Protecting groups Krzysztof Jarowicki and Philip Kocienski Department of Chemistry, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK G12 8QQ Covering: 1997 OBn H2N Previous review: Contemp. Org. Synth., 1997, 4, 454 NH NO RO O 2 3 RO SEt H2N 1 Introduction NH 3 (5 mmol) 2 Hydroxy protecting groups O 2.1 Esters O CCl3 MeONa (1 mmol) 2.2 Silyl ethers (in MeOH, 1 ml, 1 M) MeOH-CH2Cl2 2.3 Alkyl ethers 1 R = Ac 4 (6 ml) (50 ml, 9:1), rt 94% rt, 15 min 0.1 mmol scale 2.4 Alkoxyalkyl ethers 2 R = H 3 Thiol protecting groups G/GHNO3 4 Diol protecting groups 4 5 Carboxy protecting groups G = guanidine 6 Phosphate protecting groups Scheme 1 7 Carbonyl protecting groups 8 Amino protecting groups OTBS 9 Miscellaneous protecting groups 10 Reviews 11 References TESO O H OMe H 1 Introduction O O OMe The following review covers new developments in protecting OTES TBSO group methodology which appeared in 1997. As with our previ- O ous annual review, our coverage is a personal selection of OR methods which we deemed interesting or useful. Many of the O O references were selected through a Science Citation Index O search based on the root words block, protect and cleavage; AcO however, casual reading unearthed many facets of protecting OAc group chemistry which are beyond the pale of a typical key- word search. Inevitably our casual reading omits whole areas in OTES Downloaded by San Francisco State University on 14 September 2012 Published on 01 January 1998 http://pubs.rsc.org | doi:10.1039/A803688H which we lack expertise and so we cannot claim comprehensive coverage of the literature. -

Studies Toward the Total Synthesis of (+)-Pyrenolide D Honors Research

Studies toward the Total Synthesis of (+)-Pyrenolide D Honors Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in Chemistry in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Adam Doane The Ohio State University 24 May 2012 Project Advisor: Dr. Christopher Callam, Department of Chemistry i Abstract Spiro lactones have had an extensive impact in both medicinal and organismal biology. Since their discovery, various methods for preparing spiro lactones have been studied and investigated. One of these spiro lactones, pyrenolide D, which is one of the four metabolites, A- D, was isolated from Pyrenophora teres by Nukina and Hirota in 1992 and shows cytotoxicity towards HL-60 cells at IC50 4 µg/ mL. The structural determination, via spectroscopic methods, reported that unlike pyrenolides A-C, pyrenolide D contained a rare, highly oxygenated tricyclic spiro-γ-lactone structure and did not contain the macrocyclic lactone seen in the other pyrenolides. The purpose of this project is the determination of a cost effective and efficient synthesis of pyrenolide D from the naturally occurring sugar, D-xylose. Herein we report studies towards the total synthesis of pyrenolide D. i Acknowledgments I would like to thank my research advisor, Dr. Christopher Callam for his constant help, encouragement, and inspiration throughout the past 3 years. He has sacrificed an immeasurable number of hours answering questions and providing support for the duration of this project. I would also like to thank The Ohio State University Department of Chemistry for financial support as well as Chemical Abstracts Service, the William Marshall MacNevin Memorial foundation, and Mr. -

A Short, Stereocontrolled Synthesis of Strychnine'

J. Org. Chem. 1994,59, 2685-2686 2685 A Short, Stereocontrolled Synthesis of Strychnine’ Viresh H. Rawal. and Seiji Iwasa Department of Chemistry, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 43210 Received March 15, 1994” Summary: Strychnine has been synthesized by a short, highly stereocontrolled route that involves the efficient transformation of commercially available 2-nitrophen- 79% overall ylacetonitrile into isostrychnine, a known precursor to strychnine. 2 3 It was with words of awe and excitement that R. B. Woodward described “Strychnine!” (11, a heptacyclic Pyrroline 3 was converted into strychnine as described alkaloid that has fascinated organic chemists for centuries.l in Scheme 1. In the presence of an excess of unsaturated Well over 100 man years of effort, related through several aldehyde 4,6 pyrroline 3 was transformed quantitatively hundred publications, was required to secure the correct into the expected imine.8 Upon quenching the reaction structure of this natural prod~ct.~~~Soon after this mixture with excess methyl chloroformate and diethyl- achievement, in 1954 Woodward reported a brilliant aniline, the desired diene-carbamate 5 was obtained in synthesis of strychnine. Remarkably, it took nearly 40 high yield. Diene 5 underwent a smooth intramolecular years to repeat this feat, despite considerable effort from cycloaddition upon heating in benzene in a sealed tube at many groups. Over the past 2 years, however, several 185-200 “C. The reaction gave in quantitative yield and groups have reported solutions to ~trychnine.~We report with complete stereocontrol the desired tetracycle 6, with here a simple solution to the structural challenge posed three of strychnine’s stereocenters correctly set. -

Protecting Groups

Chem 6352 Protecting Groups Hydroxyl Protection Methyl Ethers OH OMe Formation: CH2N2, SiO2 or HBF4 NaH, MeI, THF Stability: Stable to Acid and Base Cleavage: AlBr3, EtSH PhSe- - Ph2P Me3SiI Adv./Disadv.: Methyl ethers, with the exception of aryl methyl ethers, are often difficult to remove. However, there are exceptions. O OMe O OH AlBr3, EtSH TL 1987, 28, 3659 O O OBz OBz Methylthiomethyl Ethers (MTM) OH O S Me Formation: MeSCH2Cl, NaH, THF Stability: Stable to base and mild acid Cleavage: HgCl2, CH3CN, H2O AgNO3, THF, H2O, base Adv./Disadv.: The MTM group is a nice substituted methyl ether protecting group that can be removed under neutral conditions employing the indicated thiophiles. Trityl Ethers OH O Ph Ph Ph Formation: Ph3CCl, pyridine, DMAP + - Ph3C BF4 Stability: Stable to Base Cleavage: Mild Acid (formic or acetic) Adv./Disadv.: The trityl group usually goes on and comes off easily. In addition, its steric bulk allows for good selectivity in protecting primary over secondary alcohols. Protection of 1,2- and 1,3-diols The protecting groups that mask 1,2- and 1,3-diols (forming either the dioxolane or dioxane, respectively) are often referred to (PREFIX)ylidenes, where the prefix depends on the nature of R and R1. O O O O R R1 R R1 dioxolane dioxane Isopropylidene (a.k.a. acetonide) HO OH O O R R1 R R1 Formation: 2,2-dimethoxy propane or 2-methoxy propene and cat. acid Stability: Stable to base Cleavage: cat. Camphor Sulfonic Acid (CSA) and MeOH Adv./Disadv.: The acetonide is commonly used to protect 1,2- and 1,3- diols. -

Synthesis of Oligodeoxynucleotides Using Fully Protected

Molecules 2010, 15, 7509-7531; doi:10.3390/molecules15117509 OPEN ACCESS molecules ISSN 1420-3049 www.mdpi.com/journal/molecules Article Synthesis of Oligodeoxynucleotides Using Fully Protected Deoxynucleoside 3′-Phosphoramidite Building Blocks and Base Recognition of Oligodeoxynucleotides Incorporating N3-Cyano-Ethylthymine Hirosuke Tsunoda, Tomomi Kudo, Akihiro Ohkubo, Kohji Seio and Mitsuo Sekine * Department of Life Science, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 4259 Nagatsuta-cho, Midori-ku, Yokohama, Japan; E-Mails: [email protected] (H.T.); [email protected] (T.K.); [email protected] (A.O.); [email protected] (K.S.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-45-924-5706; Fax: +81-45-924-5772. Received: 27 August 2010; in revised form: 8 October 2010 / Accepted: 14 October 2010 / Published: 27 October 2010 Abstract: Oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) synthesis, which avoids the formation of side products, is of great importance to biochemistry-based technology development. One side reaction of ODN synthesis is the cyanoethylation of the nucleobases. We suppressed this reaction by synthesizing ODNs using fully protected deoxynucleoside 3′-phosphoramidite building blocks, where the remaining reactive nucleobase residues were completely protected with acyl-, diacyl-, and acyl-oxyethylene-type groups. The detailed analysis of cyanoethylation at the nucleobase site showed that N3-protection of the thymine base efficiently suppressed the Michael addition of acrylonitrile. An ODN incorporating N3-cyanoethylthymine was synthesized using the phosphoramidite method, and primer extension reactions involving this ODN template were examined. As a result, the modified thymine produced has been proven to serve as a chain terminator. -

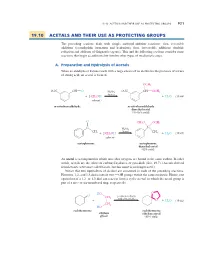

19.10 Acetals and Their Use As Protecting Groups 921

19_BRCLoudon_pgs5-0.qxd 12/9/08 11:41 AM Page 921 19.10 ACETALS AND THEIR USE AS PROTECTING GROUPS 921 19.10 ACETALS AND THEIR USE AS PROTECTING GROUPS The preceding sections dealt with simple carbonyl-addition reactions—first, reversible additions (cyanohydrin formation and hydration); then, irreversible additions (hydride reduction and addition of Grignard reagents). This and the following sections consider some reactions that begin as additions but involve other types of mechanistic steps. A. Preparation and Hydrolysis of Acetals When an aldehyde or ketone reacts with a large excess of an alcohol in the presence of a trace of strong acid, an acetal is formed. OCH3 O2N CH A O H2SO4 O2N "CH OCH3 (trace) L % % 2CH3OH % % H2O (19.44) i + (solvent) i + m-nitrobenzaldehyde m-nitrobenzaldehyde dimethyl acetal (76–85% yield) O CH O OCH S 3 3 L C L C H2SO4 L CH3 (trace) CH3 % % 2CH3OH H2O (19.45) i + (solvent) i + acetophenone acetophenone dimethyl acetal (82% yield) An acetal is a compound in which two ether oxygens are bound to the same carbon. In other words, acetals are the ethers of carbonyl hydrates, or gem-diols (Sec. 19.7). (Acetals derived from ketones were once called ketals, but this name is no longer used.) Notice that two equivalents of alcohol are consumed in each of the preceding reactions. However, 1,2- and 1,3-diols contain two OH groups within the same molecule. Hence, one equivalent of a 1,2- or 1,3-diol can react Lto form a cyclic acetal, in which the acetal group is part of a five- or six-membered ring, respectively.