Updated Default Values for Transit Dependency and Average Length

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

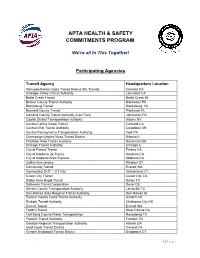

Apta Health & Safety Commitments Program

APTA HEALTH & SAFETY COMMITMENTS PROGRAM We’re all In This Together! Participating Agencies Transit Agency Headquarters Location Antelope Valley Transit Authority Lancaster CA Battle Creek Transit Battle Creek MI Blacksburg Transit Blacksburg, VA Broward County Transit Plantation FL Cambria County Transit Authority (CamTran) Johnstown PA Capital District Transportation Authority Albany NY Central Contra Costa Transit Concord CA Central Ohio Transit Authority Columbus OH Central Pennsylvania Transportation Authority York PA Champaign-Urbana Mass Transit District Urbana IL Chatham Area Transit Authority Savannah GA Chicago Transit Authority Chicago IL City of Fresno Transit Fresno CA City of Gardena (G-Trans) Gardena CA City of Modesto Area Express Modesto CA Collins Bus service Windsor CT Community Transit Everett WA Connecticut DOT -- CT Rail Glastonbury CT Culver City Transit Culver City CA Dallas Area Rapid Transit Dallas TX Delaware Transit Corporation Dover DE Denton County Transportation Authority Lewisville TX Des Moines Area Regional Transit Authority Des Moines IA Eastern Contra Costa Transit Authority Antioch CA Embark Transit Authority Oklahoma City OK Everett Transit Everett WA Foothill Transit West Covina CA Fort Bend County Public Transportation Rosenberg TX Franklin Transit Authority Franklin TN Georgia Regional Transportation Authority Atlanta GA Gold Coast Transit District Oxnard CA Greater Bridgeport Transit District Bridgeport CT Greater Hartford Transit District Harford CT Greater New Haven Transit District New Haven -

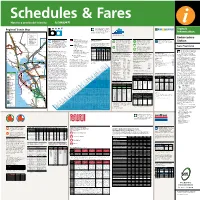

Solanoexpress Bus Routes Transit Information Fairfield Transportation Center Fairfield

Regional Transit Map Transit REGIONAL TRANSIT DIAGRAM To To Eureka Clearlake Information Mendocino Transit DOWNTOWN AREA TRANSIT CONNECTIONS Authority To Ukiah Lake Oakland Mendocino Transit 12th Street Oakland City Center BART: Greyhound BART, AC Transit FA FA 19th Street Oakland BART: FA BART, AC Transit Cloverdale San Francisco Yolobus To Davis Civic Center/UN Plaza BART: Winters Fairfi eld and Suisun Transit SolanoExpress is Solano SolanoExpress is Solano BART, Muni, Golden Gate Transit, SamTrans Fairfield 101 Embarcadero BART & Ferry Terminal: County’s intercity transit connection. County’s intercity transit connection. BART, Golden Gate Transit, Muni, SamTrans, (FAST) is the local transit system Baylink, Alameda/Oakland Ferry, Alameda Harbor Faireld and Healdsburg Bay Ferry, Blue & Gold Fleet, Amtrak CA Thruway Suisun Transit SolanoExpress routes connect cities SolanoExpress routes connect cities Transit To Sacramento for Fairfi eld and Suisun City and also Mongomery Street BART: Healdsburg BART, Muni, Golden Gate Transit, SamTrans Dixon within the county and provide service within the county and provide service Calistoga Readi- operates many of the SolanoExpress (Operated by FAST) (Operated by SolTrans) Handi Powell Street BART: Transportation Ride Van Calistoga BART, Muni, Golden Gate Transit, SamTrans regional routes. Please visit www.fasttransit. to neighboring counties, BART, and the ferry. to neighboring counties, BART, and the ferry. San Francisco Caltrain at 4th & King: Dixon Windsor Deer Caltrain, Muni, Amtrak CA Thruway org or call 707-422-BUSS (707-422-2877) for For more information, call (800) 535-6883 or For more information, call (800) 535-6883 or Park Transbay Temporary Terminal: Guerneville AC Transit, Muni, Golden Gate Transit, SamTrans, 80 visit www.solanoexpress.com. -

Smart Location Database Technical Documentation and User Guide

SMART LOCATION DATABASE TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION AND USER GUIDE Version 3.0 Updated: June 2021 Authors: Jim Chapman, MSCE, Managing Principal, Urban Design 4 Health, Inc. (UD4H) Eric H. Fox, MScP, Senior Planner, UD4H William Bachman, Ph.D., Senior Analyst, UD4H Lawrence D. Frank, Ph.D., President, UD4H John Thomas, Ph.D., U.S. EPA Office of Community Revitalization Alexis Rourk Reyes, MSCRP, U.S. EPA Office of Community Revitalization About This Report The Smart Location Database is a publicly available data product and service provided by the U.S. EPA Smart Growth Program. This version 3.0 documentation builds on, and updates where needed, the version 2.0 document.1 Urban Design 4 Health, Inc. updated this guide for the project called Updating the EPA GSA Smart Location Database. Acknowledgements Urban Design 4 Health was contracted by the U.S. EPA with support from the General Services Administration’s Center for Urban Development to update the Smart Location Database and this User Guide. As the Project Manager for this study, Jim Chapman supervised the data development and authored this updated user guide. Mr. Eric Fox and Dr. William Bachman led all data acquisition, geoprocessing, and spatial analyses undertaken in the development of version 3.0 of the Smart Location Database and co- authored the user guide through substantive contributions to the methods and information provided. Dr. Larry Frank provided data development input and reviewed the report providing critical input and feedback. The authors would like to acknowledge the guidance, review, and support provided by: • Ruth Kroeger, U.S. General Services Administration • Frank Giblin, U.S. -

Solano Express Bus Routes Transit Information Pleasant Hill Station Area Contra Costa Centre

Fare Information effective January 1, 2016 Senior3 Adult/ (65+) Youth2 County Connection & (6-64) For more detailed information about BART Disabled service, please see the BART Schedule, BART 1 Transit CASH FARES (exact change only) Regional Transit Map System Map, and other BART information REGIONAL TRANSIT DIAGRAM displays in this station. Regular Ride $2.00 $1.00 To To Express Ride (900 series route numbers) $2.25 $1.00 Eureka Clearlake Information Mendocino Transit DOWNTOWN AREA TRANSIT CONNECTIONS PREPAID FARES Authority To Ukiah Lake Oakland ® 4 $2.00 $1.00 Mendocino Transit 12th Street Oakland City Center BART: Clipper Cash Value Greyhound BART, AC Transit 19th Street Oakland BART: 5 $3.75 $1.75 BART, AC Transit Day Pass Cloverdale San Francisco Yolobus To Davis Discount Regular/Express 20-Ride Pass N/A $15.00 Civic Center/UN Plaza BART: Winters BART, Muni, Golden Gate Transit, SamTrans Commuter Card (20 Regular+BART Transfer-Rides) $40.00 N/A Pleasant Hill 101 Embarcadero BART & Ferry Terminal: BART, Golden Gate Transit, Muni, SamTrans, Baylink, Alameda/Oakland Ferry, Alameda Harbor Faireld and 6 $60.00 N/A Healdsburg Bay Ferry, Blue & Gold Fleet, Amtrak CA Thruway Suisun Transit East Bay Regional Local 31-Day Transit To Sacramento Mongomery Street BART: Healdsburg BART, Muni, Golden Gate Transit, SamTrans Dixon 6 $70.00 N/A Calistoga Readi- County Connection (CCCTA) effective January 1, 2016 East Bay Regional Express 31-Day Handi Powell Street BART: San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Fare Information Station Area Ride BART Red* Ticket -

FY 2016-17 LCTOP List of Awarded Projects

State of California • Department of Transportation NEW RELEASE Date: July 3, 2017 District: Headquarters Contact: Vanessa Wiseman Phone: (916) 654-2936 Contact: Tamie McGowen Phone: (916) 657-5060 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE More Than $34 Million Awarded to 125 Projects Under Cap-and-Trade Fund 85 Percent of the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Funding Will Benefit Disadvantaged Communities SACRAMENTO – Caltrans today announced that 125 local projects received $34.5 million in funding from the Low Carbon Transit Operations Program. These projects continue California’s effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve the sustainability of public transportation systems around the state. “This program is one of the methods Caltrans is using to help the state meet its ambitious goals to address climate change,” said Caltrans Director Malcolm Dougherty. “Building a more sustainable public transportation system involves not only making it more climate friendly, but also more efficient and affordable to more Californians.” The Low Carbon Transit Operations Program is one of several state programs which are funded through auction proceeds from the California Air Resources Board’s Cap- and-Trade Program into the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. Funding from this program goes toward direct investments in transit projects that reduce GHG emissions and benefit disadvantaged communities throughout California. These projects are part of the California Climate Investments, which provide a variety of additional benefits to California communities. Some of the local projects that will benefit from these funding disbursements include: • Expanded Service on the 9R: $3,764,725 to the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency to expand transit service on Route 9R San Bruno Rapid Line, increasing mobility and encouraging a greater use of transit. -

Fy19-20 Low Carbon Transit Operations Program Allocation Award List

Caltrans-Division of Rail and Mass Transportation FY19-20 LOW CARBON TRANSIT OPERATIONS PROGRAM ALLOCATION AWARD LIST Disadvantaged Low 1/2 Mile Low- Community Income Income Buffer Total Project Project Benefit Benefit Benefit Request SB 1119 District Project ID Lead Agency: Project Name: Type: Project Description (Short): FY19-20 City of Arcata (Arcata Mad River Transit To allow Free Transit to encourage ridership on Arcata Mad River Transit NO YES NO #N/A 1 19-20-D01-001 System) AMRTS Free Fares Operations System $13,339 This project will provide reduced fares and free ticket vouchers to raise Humboldt Transit Reduced Fares and Free awareness of public transportation. This will give riders an opportunity to NO YES NO #N/A 1 19-20-D01-002 Authority Ticket Vouchers Operations try transit at no cost. $303,307 This project provides for the purchase and installation of a solar canopy to cover the bus parking lot. The canopy will provide enough electricity to power four electric buses and the operations facility. The canopy will also shade the lot, reducing the time buses are idling prior to inspection and NO YES NO #N/A 1 19-20-D01-003 Lake Transit Authority Solar Canopy Project Capital start-up. $102,736 The project will provide unlimited free use of Lake Transit Authority bus routes anywhere in Lake, Napa, or Mendocino counties for the following: Free Fares for Community (1) any Mendocino College or Woodland College student displaying a College Students and the valid student identification and (2) any child between the age of 7 and 17 NO YES NO #N/A 1 19-20-D01-004 Lake Transit Authority Summer Cruisin' Program Operations between June 15 and August 31 (known as the Summer Cruisin' Program) $23,351 RCTA will use LCTOP funding in a three-year bus electrification project, planning an installing an electric recharge facility and augmenting an FTA bus grant to purchase an electric powered vehicle. -

Regional Transit Diagram for Real-Time Departure Information, Check Nearby Displays

Regional Transit Diagram For Real-Time Departure Information, check nearby displays. Or, you can call Transit Regional Transit Map 511 and say “Departure Times.” For Free Transit Information Free Transit Information more details, look for the 511 Real-Time Call 511 or Visit 511.org REGIONAL TRANSIT DIAGRAM Call 511 or Visit 511.org To To Departure Times description in the “Transit Eureka Clearlake Information” column on the right. Information Mendocino Transit DOWNTOWN AREA TRANSIT CONNECTIONS Authority To Ukiah Lake Oakland Mendocino Transit 12th Street Oakland City Center BART: Greyhound BART, AC Transit 19th Street Oakland BART: BART, AC Transit Cloverdale San Francisco Yolobus To Davis Civic Center/UN Plaza BART: Winters BART, Muni, Golden Gate Transit, SamTrans Embarcadero 101 Embarcadero BART & Ferry Terminal: BART, Golden Gate Transit, Muni, SamTrans, Baylink, Alameda/Oakland Ferry, Alameda Harbor Faireld and Healdsburg Bay Ferry, Blue & Gold Fleet, Amtrak CA Thruway Suisun Transit BART Red* Ticket Transit To Sacramento San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Harbor Bay/San Francisco Route Vallejo/San Francisco Ferry and Blue & Gold Fleet operates Mongomery Street BART: Schedule Information Healdsburg BART, Muni, Golden Gate Transit, SamTrans Dixon 62.5% discount for persons with Calistoga Readi- Transit (BART) rail service connects operates weekdays only between Bus Routes operate weekdays, weekday ferry service from the Handi Powell Street BART: effective September 10, 2012 Station Ride disabilities, Medicare cardholders Van Calistoga BART, Muni, Golden Gate Transit, SamTrans the San Francisco Peninsula with Alameda’s Harbor Bay Isle and the weekends, and some holidays San Francisco Ferry Terminal to San Francisco Caltrain at 4th & King: Dixon and children 5 to 12 years: $24 Windsor Deer Caltrain, Muni, Amtrak CA Thruway Oakland, Berkeley, Fremont, See schedules posted throughout this station, San Francisco Ferry Building. -

Sjcog Unmet Transit Needs Fy 2020‐2021

SJCOG UNMET TRANSIT NEEDS FY 2020‐2021 SJCOG UNMET TRANSIT NEEDS FY 2020‐2021 back SJCOG UNMET TRANSIT NEEDS FY 2020‐2021 THE SAN JOAQUIN COUNCIL OF GOVERNMENTS BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chair Robert Rickman City of Tracy Vice Chair Doug Kuehne City of Lodi Boardmember Walt Murken City of Escalon Boardmember Gary Singh City of Manteca Boardmember Leo Zuber City of Ripon Boardmember Sonny Dhaliwal City of Lathrop City Boardmember Katherine Miller San Joaquin County Boardmember Sol Jobrack City of Stockton Boardmember Jesús Andrade City of Stockton Boardmember Dan Wright City of Stockton Boardmember Bob Elliott San Joaquin County Boardmember Chuck Winn San Joaquin County EX‐OFFICO MEMBERS Dan McElhinney Caltrans District 10 Gary S. Giovanetti San Joaquin Regional Transit District Anthony Barkett Port of Stockton SJCOG UNMET TRANSIT NEEDS FY 2020‐2021 SAN JOAQUIN COUNCIL OF GOVERNMENTS PROFESSIONAL STAFF Andrew T. Chesley Executive Director Steve Dial Deputy Executive Director/Chief Financial Officer Diane Nguyen Deputy Director, Planning, Programming & Project Delivery Rebecca Calija Manager of Administrative Services Gracie Orosco Chief Accountant Vikram Sharma Information Services Manager Steve Mayo Project Manager Ryan Niblock Senior Regional Planner Kim Kloeb Senior Regional Planner Yvette Davis Senior Program Specialist David Ripperda Senior Regional Planner Christine Corrales Associate Regional Planner Travis Yokoyama Associate Regional Planner Laurel Boyd Associate Habitat Planner Joel Campos Associate Program Assistant Ashley Goldlist Regional -

Tri-Valley Hub Network Integration Study Final Report

Tri-Valley Hub Network Integration Study Final Report May 20, 2021 ES-1 Final Report Tri-Valley Hub Network Integration Study Tri-Valley Hub Network Integration Study Final Report Prepared by Livermore Amador Valley Transit Authority (LAVTA) May 20, 2021 Executive Summary The 2018 California State Rail Plan envisions a network of high-speed, intercity corridor, and commuter trains integrated with local transit, providing nearly seamless connections for riders seeking to reach all parts of the state. In corridors where no trains operate, the Rail Plan calls for express buses using the existing highway systems to provide access to the state’s rail system. The Rail Plan identified the I-680 corridor between the Tri-Valley area (i.e. Dublin, Pleasanton, and Livermore) and Suisun City as one such corridor, where express buses could link a Tri-Valley Transit Hub with the Suisun-Fairfield Amtrak Station, a stop for the Capitol Corridor trains. This Tri-Valley Hub Network Integration Study is an effort to define what such express bus service would be: its route, stops, connections with corridor and commuter trains, as well as its likely ridership, revenue, and costs for implementation. The study investigates the BART Dublin/Pleasanton BART station as a candidate for the Tri-Valley Transit Hub, along with potential improvements that could make the facility easier, safer, and more comfortable for riders to use. The study also explores options to better connect northern San Joaquin County communities with the Tri-Valley Hub. The distance between the Suisun Amtrak Station and the Dublin/Pleasanton BART Station is 53 miles, inclusive of a stop at the Martinez Amtrak Station. -

Modesto Transit Center Project Historic Resource Report

Historic Resource Report for Modesto Transit Center Improvements at the former Modesto Southern Pacific Railroad Depot 1029 9th Street Modesto, California 95354 Prepared for: Modesto Area Express Transit 1010 Tenth Street Modesto, CA 95353 Prepared by: JRP Historical Consulting, LLC 2850 Spafford Street Davis, CA 95618 September 2019 Modesto Transit Center Improvements Historic Resource Report 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary................................................................................................................ 1 2. Project Description.................................................................................................................. 4 3. Area of Potential Effects....................................................................................................... 13 4. Identification of Historic Properties...................................................................................... 14 4.1. Methodology for Identification of Historic Properties................................................... 14 4.2. Update Historic Evaluation of former Modesto SPRR Station...................................... 16 4.3. Former Modesto SPRR Station Character-Defining Features ....................................... 17 5. Conclusion ............................................................................................................................ 26 6. Preparers’ Qualifications ...................................................................................................... 26 APPENDIX -

1.7.3 Project Environmental Impact Report

Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Introduction The Tri-Valley–San Joaquin Valley Regional Rail Authority (Authority) is proposing the Valley Link Project, which is being evaluated on a project level in this Draft Environmental Impact Report (Draft EIR). This chapter provides a brief overview of the Proposed Project and alternatives; the Project goals and objectives; Project background and context; an overview of the environmental review process; and the scope, content, and organization of the Draft EIR. Figure 1-1. Valley Link Project Geographic Segments 1.2 Project Overview 1.2.1 Proposed Project The Proposed Project is a new 42-mile, 7-station passenger rail project that will connect the existing Dublin/Pleasanton Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) Station in Alameda County to the approved Altamont Corridor Express (ACE) North Lathrop Station in San Joaquin County (Figure 1-1). Valley Link will use existing transportation corridors: the existing Interstate (I-) 580 corridor (11.7 miles) in the Tri-Valley; the Alameda County Transportation Corridor right-of-way (ROW) through the Altamont Pass (14.5 miles); and the existing Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) Corridor (16.1 miles) in Northern San Joaquin County. The Proposed Project includes the following stations: ⚫ Dublin/Pleasanton (BART Intermodal) Valley Link Draft EIR 1-1 December 2020 ICF 00004.19 Tri-Valley – San Joaquin Valley Regional Rail Authority Introduction ⚫ Isabel (Livermore) ⚫ Greenville (Livermore) ⚫ Mountain House (San Joaquin County) ⚫ Downtown Tracy Station (Tracy) ⚫ River Islands Station (Lathrop) ⚫ North Lathrop Station (ACE Intermodal) The Proposed Project also includes the proposed Tracy Operation and Maintenance Facility (OMF), which would be located in the City of Tracy. -

Apta Health & Safety Commitments Program

APTA HEALTH & SAFETY COMMITMENTS PROGRAM We’re all In This Together! Participating Agencies Transit Agency Headquarters Location Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District (AC Transit) Oakland CA Antelope Valley Transit Authority Lancaster CA Battle Creek Transit Battle Creek MI Beaver County Transit Authority Rochester PA Blacksburg Transit Blacksburg, VA Broward County Transit Plantation FL Cambria County Transit Authority (CamTran) Johnstown PA Capital District Transportation Authority Albany NY Central Contra Costa Transit Concord CA Central Ohio Transit Authority Columbus OH Central Pennsylvania Transportation Authority York PA Champaign-Urbana Mass Transit District Urbana IL Chatham Area Transit Authority Savannah GA Chicago Transit Authority Chicago IL City of Fresno Transit Fresno CA City of Gardena (G-Trans) Gardena CA City of Modesto Area Express Modesto CA Collins Bus service Windsor CT Community Transit Everett WA Connecticut DOT -- CT Rail Glastonbury CT Culver City Transit Culver City CA Dallas Area Rapid Transit Dallas TX Delaware Transit Corporation Dover DE Denton County Transportation Authority Lewisville TX Des Moines Area Regional Transit Authority Des Moines IA Eastern Contra Costa Transit Authority Antioch CA Embark Transit Authority Oklahoma City OK Everett Transit Everett WA Foothill Transit West Covina CA Fort Bend County Public Transportation Rosenberg TX Franklin Transit Authority Franklin TN Georgia Regional Transportation Authority Atlanta GA Gold Coast Transit District Oxnard CA Greater Bridgeport Transit District