Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Training in Internal Medicine Residents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internal Medicine Milestones

Internal Medicine Milestones The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Implementation Date: July 1, 2021 Second Revision: November 2020 First Revision: July 2013 ©2020 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) All rights reserved except the copyright owners grant third parties the right to use the Internal Medicine Milestones on a non-exclusive basis for educational purposes. Internal Medicine Milestones The Milestones are designed only for use in evaluation of residents in the context of their participation in ACGME-accredited residency programs. The Milestones provide a framework for the assessment of the development of the resident in key dimensions of the elements of physician competency in a specialty or subspecialty. They neither represent the entirety of the dimensions of the six domains of physician competency, nor are they designed to be relevant in any other context. ©2020 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) All rights reserved except the copyright owners grant third parties the right to use the Internal Medicine Milestones on a non-exclusive basis for educational purposes. i Internal Medicine Milestones Work Group Eva Aagaard, MD, FACP Jonathan Lim, MD Cinnamon Bradley, MD Monica Lypson, MD, MHPE Fred Buckhold, MD Allan Markus, MD, MS, MBA, FACP Alfred Burger, MD, MS, FACP, SFHM Bernadette Miller, MD Stephanie Call, MD, MSPH Attila Nemeth, MD Shobhina Chheda, MD, MPH Jacob Perrin, MD Davoren Chick, MD, FACP Raul Ramirez Velazquez, DO Jack DePriest, MD, MACM Rachel Robbins, MD Benjamin Doolittle, MD, MDiv Jacqueline Stocking, PhD, MBA, RN Laura Edgar, EdD, CAE Jane Trinh, MD Christin Giordano McAuliffe, MD Mark Tschanz, DO, MACM Neil Kothari, MD Asher Tulsky, MD Heather Laird-Fick, MD, MPH, FACP Eric Warm, MD Advisory Group Mobola Campbell-Yesufu, MD, MPH Subha Ramani, MBBS, MMed, MPH Gretchen Diemer, MD Brijen Shah, MD Jodi Friedman, MD C. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

2019‐2020 Internal Medicine Residency Handbook Table of Contents Contacts

2019‐2020 Internal Medicine Residency Handbook Table of Contents Contacts ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Compact ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Core Tenets of Residency ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Program Requirements ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Resident Recruitment/Appointments .............................................................................................. 9 Background Check Policy ................................................................................................................ 10 New Innovations ............................................................................................................................. 11 Social Networking Guidelines ......................................................................................................... 11 Dress Code ...................................................................................................................................... 12 Resident’s Well Being ...................................................................................................................... 13 Academic Conference Attendance ................................................................................................ -

ACGME Specialties Requiring a Preliminary Year (As of July 1, 2020) Transitional Year Review Committee

ACGME Specialties Requiring a Preliminary Year (as of July 1, 2020) Transitional Year Review Committee Program Specialty Requirement(s) Requirements for PGY-1 Anesthesiology III.A.2.a).(1); • Residents must have successfully completed 12 months of IV.C.3.-IV.C.3.b); education in fundamental clinical skills in a program accredited by IV.C.4. the ACGME, the American Osteopathic Association (AOA), the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC), or the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC), or in a program with ACGME International (ACGME-I) Advanced Specialty Accreditation. • 12 months of education must provide education in fundamental clinical skills of medicine relevant to anesthesiology o This education does not need to be in first year, but it must be completed before starting the final year. o This education must include at least six months of fundamental clinical skills education caring for inpatients in family medicine, internal medicine, neurology, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, surgery or any surgical specialties, or any combination of these. • During the first 12 months, there must be at least one month (not more than two) each of critical care medicine and emergency medicine. Dermatology III.A.2.a).(1)- • Prior to appointment, residents must have successfully completed a III.A.2.a).(1).(a) broad-based clinical year (PGY-1) in an emergency medicine, family medicine, general surgery, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, or a transitional year program accredited by the ACGME, AOA, RCPSC, CFPC, or ACGME-I (Advanced Specialty Accreditation). • During the first year (PGY-1), elective rotations in dermatology must not exceed a total of two months. -

Internal Medicine Interest Group Resource Guide

Making the Most of Your Internal Medicine Interest Group: A Practical Resource Guide Developed by the Council of Student Members June 2015 EX4038 Table of Contents Introduction to Internal Medicine Interest Groups................................................................................1 Establishing an IMIG at your School........................................................................................................1 Best Practices for IMIGs ............................................................................................................................3 Holding an Internal Medicine Residency Fair ........................................................................................8 Appendix....................................................................................................................................................9 Introduction to Internal Establishing an IMIG at Your School Medicine Interest Groups You should seek advice from as many resources as possible during the planning An internal medicine interest group (IMIG) is stages. Be sure to consult with your school’s an organized group of medical students who administration about how to establish an meet regularly to learn about internal medi- official club at your school. Once the group’s cine and to establish communication with leadership is established, an e-mail should be faculty and other students who share similar sent out to all group members to poll them interests. IMIGs have a faculty advisor who about activities in which they -

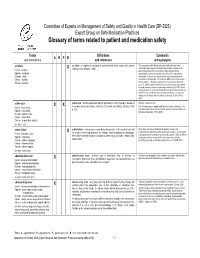

Glossary of Terms Related to Patient and Medication Safety

Committee of Experts on Management of Safety and Quality in Health Care (SP-SQS) Expert Group on Safe Medication Practices Glossary of terms related to patient and medication safety Terms Definitions Comments A R P B and translations and references and synonyms accident accident : an unplanned, unexpected, and undesired event, usually with adverse “For many years safety officials and public health authorities have Xconsequences (Senders, 1994). discouraged use of the word "accident" when it refers to injuries or the French : accident events that produce them. An accident is often understood to be Spanish : accidente unpredictable -a chance occurrence or an "act of God"- and therefore German : Unfall unavoidable. However, most injuries and their precipitating events are Italiano : incidente predictable and preventable. That is why the BMJ has decided to ban the Slovene : nesreča word accident. (…) Purging a common term from our lexicon will not be easy. "Accident" remains entrenched in lay and medical discourse and will no doubt continue to appear in manuscripts submitted to the BMJ. We are asking our editors to be vigilant in detecting and rejecting inappropriate use of the "A" word, and we trust that our readers will keep us on our toes by alerting us to instances when "accidents" slip through.” (Davis & Pless, 2001) active error X X active error : an error associated with the performance of the ‘front-line’ operator of Synonym : sharp-end error French : erreur active a complex system and whose effects are felt almost immediately. (Reason, 1990, This definition has been slightly modified by the Institute of Medicine : “an p.173) error that occurs at the level of the frontline operator and whose effects are Spanish : error activo felt almost immediately.” (Kohn, 2000) German : aktiver Fehler Italiano : errore attivo Slovene : neposredna napaka see also : error active failure active failures : actions or processes during the provision of direct patient care that Since failure is a term not defined in the glossary, its use is not X recommended. -

2020-2021 Internal Medicine Residency

2020-2021 Internal Medicine Residency Internal Medicine Assistant Chiefs of Service Aribindi, Katyayini Bhandari, Karthik Chen, Jeffrey Huq, Carissa University of Miami Miller University of Texas Texas Tech University Texas A&M University School of Medicine Medical School at Health Sciences Center System Health Sciences Houston School of Medicine Center College of Medicine Internal Medicine Preliminary PGY 1 (15) Akinseye, Oyindamola Brown, Ashley Burke, Michael Drozd, Brandy Hasegawa, Naomi UT Southwestern UT McGovern UT McGovern UT McGovern UT McGovern Medical School Medical School Medical School Medical School Hopkins, Christina Kim, Ryan Kiser, Kendall Lines, Tanner Nyalakonda, Baylor UT McGovern UT McGovern Texas A&M Ramitha Medical School Medical School Oakland University Patel, Saagar Redko, Alissa Rose, Kevelyn Sahihi, Aaron Sanchez, Ashley UT McGovern UT McGovern UT McGovern UT McGovern UT McGovern Medical School Medical School Medical School Medical School Medical School Internal Medicine Categorical PGY 1 (40) Adimora, Ijele Mohammad Amatullah, Atia Bajwa, Daniel Baruch, Erez Alsheikh-Kassim Dartmouth UT McGovern Texas Tech University of Texas Sackler Medical School Rio Grande Valley Bertini, Christopher Box, Nathan Cham, Brent Chernis, Julia Chopra, Maneera UT McGovern Texas A&M USF Health Morsani UT McGovern UT McGovern Medical School Medical School Medical School Akshar, Dash Datar, Saumil Farmer, Lindsey Gaglani, Tanmay Garrison, Keith Texas Tech University UT McGovern Texas A&M UT McGovern University of Texas Medical School -

NAMCS Factsheet for Internal Medicine (2010)

National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Factsheet INTERNAL MEDICINE In 2010, there were an estimated The major reason for visit was: 139 million visits to nonfederally New problem — 37% employed, office-based physicians Chronic problem, routine — 32% specializing in internal medicine in Preventative care — 19% the United States. Over 75 percent of the visits were made by persons 45 Chronic problem, flare-up — 8% years and over. Pre- or post-surgery/injury follow-up — 2% Percent distribution of office visits by patient’s age: 2010 The top 4 reasons given by patients for visiting internists were: 39 40 General medical exam 35 Progress visit 30 Hypertension 25 21 20 18 17 Cough 15 Percent of visits 10 5 The top 4 diagnoses were: 5 Essential hypertension 0 <25 25–44 45–64 65–74 75+ Diabetes mellitus Patient’s age in years General medical exam The annual visit rate increased with Disorders of lipid metabolism age. Females had a higher visit rate than males. Medications were provided or Annual office visit rates by patient’s prescribed at 87 percent of office visits. age and sex: 2010 The top 5 generic substances utilized were: <25 6 Aspirin 25–44 32 Simvastatin 45–64 69 Lisinopril 65–74 113 Levothyroxine 75+ 163 Omeprazole 41 For more information, contact the Male Ambulatory and Hospital Care Statistics Female 51 Branch at 301-458-4600 or visit our Web site at <www.cdc.gov/namcs>. Number of visits per 100 persons per year Expected source(s) of payment included: Private insurance — 50% Medicare — 36% Medicaid/CHIP — 5% No insurance1 — 3% 1 No insurance is defined as having only self-pay, no charge, or charity visits as payment sources. -

PGY1 – Internal Medicine – Focus on Cardiology Learning Experience

CONTROLLED UNLESS PRINTED PGY1 – Internal Medicine – Focus on Cardiology Learning Experience Preceptors* Shane VanHandel, PharmD ([email protected]) Randy Bahm, RPh ([email protected]) Therese Wavrin, RPh ([email protected]) Tom Wavrin, RPh ([email protected]) Deborah Sanchez, PharmD, BCPS, MHA ([email protected]) Immanuel Ijo, PharmD, BCPS ([email protected]) *Primary preceptors and preceptors will be assigned dependent on pharmacist schedule during rotation General Description During this 4-week rotation the resident will be assigned to work with a pharmacist on the Asante Rogue Regional Medical Center cardiology unit to monitor patients' drug therapies in the inpatient setting. The shift hours are 0700 to 1730. The clinical pharmacist on the cardiology team is responsible for ensuring safe and effective medication use for all patients admitted to the cardiac care floor. Routine responsibilities include: review of heart failure medication regimens, completion of consults and medication therapy protocols in areas including dosing and monitoring of TPN, kinetics, and warfarin, evaluation of anti-infectives, renal dosing, completion of medication history review follow-ups, IV to PO conversions, addressing formal consults for non-formulary drug requests and providing patient education. The pharmacist also provides drug information and education to healthcare professionals as requested. Expectations of the Resident It is expected that the resident will focus on learning cardiac related disease states encountered and then apply that knowledge to the care of the patients on service. The resident will be exposed to opportunities to teach students, patients, and other health care providers. The resident will be participating in and be responsible for the same activities that are expected of the clinical pharmacist. -

ACGME Program Requirements for Internal Medicine Residency

ACGME Program Requirements for Residency Education in Internal Medicine Common Program Requirements are in BOLD Effective: July 1, 2007 I. Institutions A. Sponsoring Institution One sponsoring institution must assume the ultimate responsibility for the program, as described in the Institutional Requirements, and this responsibility extends to resident assignments at all participating sites. The sponsoring institution and program must ensure that the program director has sufficient protected time and financial support for his or her educational and administrative responsibilities. The sponsoring institution must: 1. provide resident compensation and benefits, faculty, facilities, and resources for education, clinical care, and research required for accreditation; 2. provide at least 50% salary support for the program director; 3. provide 20 hours per week salary support for each associate program director required to meet these program requirements; 4. demonstrate a commitment to education and research sufficient to support the residency program; and, 5. establish the internal medicine residency within a department of internal medicine or an administrative unit whose primary mission is the advancement of internal medicine education and patient care; B. Participating Sites 1. There must be a program letter of agreement (PLA) between the program and each participating site providing an assignment. The PLA must be renewed at least every five years. The PLA should: a) identity the faculty who will assume both educational and supervisory responsibilities for residents; b) specify their responsibilities for teaching, supervision, and formal evaluation of residents, as specified later in this document; c) specify the duration and content of the educational experience; and, d) state the policies and procedures that will govern resident education during the assignment. -

Roadmap to Choosing a Medical Specialty Questions to Consider

Roadmap to Choosing a Medical Specialty Questions to Consider Question Explanation Examples What are your areas of What organ system or group of diseases do you Pharmacology & Physiology à Anesthesia scientific/clinical interest? find most exciting? Which clinical questions do Anatomy à Surgical Specialty, Radiology you find most intriguing? Neuroscience à Neurology, Neurosurgery Do you prefer a surgical, Do you prefer a specialty that is more Surgical à Orthopedics, Plastics, Neurosurgery medical, or a mixed procedure-oriented or one that emphasizes Mixed à ENT, Ob/Gyn, EMed, Anesthesia specialty? patient relationships and clinical reasoning? Medical à Internal Medicine, Neurology, Psychiatry See more on the academic advising website. What types of activities do Choose a specialty that will allow you to pursue Your activity options will be determined by your practice you want to engage in? your non-medical interests, like research, setting & the time constraints of your specialty. Look at teaching or policy work. the activities physicians from each specialty engage in. How much patient contact Do you like talking to patients & forming Internal & Family Medicine mean long-term patient and continuity do you relationships with them? What type of physical relationships. Radiology & Pathology have basically no prefer? interaction do you want with your patients? patient contact. Anesthesiologists & EMed docs have brief and efficient patient interactions. What type of patient Look at the typical patient populations in each Oncologists have patients with life-threatening diseases. population would you like specialty you’re considering. What type of Pediatricians may deal with demanding parents as well as to work with? physician-patient relationship do you want? sick infants and children. -

What Is Internal Medicine?

ON BEING A DOCTOR What Is Internal Medicine? Y ou have had those moments of uncommon richness: boundaries of an organ system or a technique into the the sudden intimate connection with a friend, or the realm of diagnosis. And his or her gift of diagnosis birth of a child, or the irresistible impulse to thought- flows from a sound knowledge of the science of the fulness. (Why are they so few, these epiphanies? Is it subspecialties, and from the art of medicine. Watch because we get caught up with the ordinary, intending these doctors in action and ask how it was they arrived to save these special moments, yet never quite return to at the answer. The best of them will seem to have them? Do we get sidetracked, never to get back to that intuited the solution to the problem, yet will explain special divergence that might give life meaning?) retrospectively the logical steps to the answer—as does Medicine is no different. We have our special mo- the mathematician who skips several steps in his proof. ments in medicine, moments laced with a sense of priv- This internist will consult for surgeons, and for family ilege. There is that first day in the dissection room practitioners, on matters relating to infectious diseases where a mystery unfolds. The human body opens be- and antibiotic use, on questions of endocrinology and fore you and you find you are not repulsed after all. It whether the thyroid is enlarged and overactive or just even holds your interest. But more than that.