Internal Medicine Recruiting Trends and Recommendations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internal Medicine Milestones

Internal Medicine Milestones The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Implementation Date: July 1, 2021 Second Revision: November 2020 First Revision: July 2013 ©2020 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) All rights reserved except the copyright owners grant third parties the right to use the Internal Medicine Milestones on a non-exclusive basis for educational purposes. Internal Medicine Milestones The Milestones are designed only for use in evaluation of residents in the context of their participation in ACGME-accredited residency programs. The Milestones provide a framework for the assessment of the development of the resident in key dimensions of the elements of physician competency in a specialty or subspecialty. They neither represent the entirety of the dimensions of the six domains of physician competency, nor are they designed to be relevant in any other context. ©2020 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) All rights reserved except the copyright owners grant third parties the right to use the Internal Medicine Milestones on a non-exclusive basis for educational purposes. i Internal Medicine Milestones Work Group Eva Aagaard, MD, FACP Jonathan Lim, MD Cinnamon Bradley, MD Monica Lypson, MD, MHPE Fred Buckhold, MD Allan Markus, MD, MS, MBA, FACP Alfred Burger, MD, MS, FACP, SFHM Bernadette Miller, MD Stephanie Call, MD, MSPH Attila Nemeth, MD Shobhina Chheda, MD, MPH Jacob Perrin, MD Davoren Chick, MD, FACP Raul Ramirez Velazquez, DO Jack DePriest, MD, MACM Rachel Robbins, MD Benjamin Doolittle, MD, MDiv Jacqueline Stocking, PhD, MBA, RN Laura Edgar, EdD, CAE Jane Trinh, MD Christin Giordano McAuliffe, MD Mark Tschanz, DO, MACM Neil Kothari, MD Asher Tulsky, MD Heather Laird-Fick, MD, MPH, FACP Eric Warm, MD Advisory Group Mobola Campbell-Yesufu, MD, MPH Subha Ramani, MBBS, MMed, MPH Gretchen Diemer, MD Brijen Shah, MD Jodi Friedman, MD C. -

How Many Physicians Do You Need?

How Many Physicians Do You Need? Dear Reader: I hope you enjoy the following excerpt from the HealthLeaders Media book, The Hospital Executive’s Guide to Physician Staffing Complete with proven staffing models and current data on physician supply and demand, this book helps answer a ORDER question that healthcare analysts and policymakers have YOUR COPY debated for nearly 30 years: How many physicians do we need? ONLINE! This insightful, data-rich, and timely resource outlines proven approaches for determining physician need for a broad range of markets and specialties. The book also offers sound strategies for building productive relationships with physicians by creating a culture that embraces high-quality physicians and gives them a significant role in shared decision-making. Choose one of the following ways to order you copy today » Online: At HealthLeaders Media—www.healthleadersmedia.com/books » By phone: Call our customer service department at 800/753-0131 » By fax: Complete the order form on the last page and fax to 800/639-8511 Thank you, Matthew G. Cann Group Publisher HealthLeaders Media A division of HCPro, Inc P.O. Box 1168 | Marblehead, MA 01945 | 800/753-0131 | www.healthleadersmedia.com C HAPTER 4 How Many Physicians Make a Health System? As noted at the beginning of Chapter 3, determining community physician need is an important task for hospitals and health systems, especially those seeking to enhance clinical programs or dealing with current or anticipated physician shortages. However, there are many aspects of medical staff plan- ning and development that are outside the scope of a community need analy- sis or require more detailed investigation. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Enhancing Health Care Through Telehealth

Enhancing Health Care through Telehealth Telehealth is making a difference UnityPoint Health is using telehealth to provide greater access to high-quality care while driving down overall health care costs. ENHANCED ACCESS TO CARE Telehealth keeps patients and families connected to vital health care services. Over the last seven months, UnityPoint Health has: • Seen an increase in telehealth visits of more than 1,700%. • Grown the number specialties offering telehealth from 15 to 51. • Equipped more than 1,800 clinicians to provide telehealth services. Visits Specialties Clinicians 250,000 60 2000 1860 210,841 51 50 200,000 1500 40 150,000 30 1000 100,000 20 15 500 50,000 11,336 10 78 - 0 0 Pre During Pre During Pre During Pre = Aug 2019 - Jan 2020 During = Feb - Jul 2020 EXPANDING THE USE OF TELEHEALTH UnityPoint Health is making telehealth available in homes, workplaces, clinics, hospitals, emergency rooms, nursing facilities and much more. Direct to patient virtual care services, both on-demand and scheduled • Urgent care visits • Follow up visits with a primary care physician • Behavioral health visits • More than 50 other types of specialist visits Provider to provider telehealth services • Inpatient hospital support • Intensive care unit support • Emergency room support EMPHASIS ON PATIENT-CENTERED CARE A Patient's Perspective When it came time for his annual wellness visit, Scott Frank considered cancelling due to his busy schedule. He then learned he could have his visit virtually. Soon after scheduling his appointment, he was disking a field when he stopped his tractor to talk with his primary care provider. -

Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Training in Internal Medicine Residents

Clinical AND Health Affairs Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Training in Internal Medicine Residents BY MOLLIE ALPERN, MD, QI WANG, MS, AND MEGHAN ROTHENBERGER, MD Common allergic conditions such as allergic rhinitis, asthma and antibiotic allergies are frequently encountered by internal medicine physicians. These conditions are a significant source of health care utilization and morbidity. However, many internal medicine residency programs offer limited training in allergy and immunology. Internal medicine residents’ significant knowledge deficits regarding allergy-related content have been previously identified. We conducted a survey-based study to examine the knowledge and self-assessed clinical competency of residents at an academic medical center to determine the need for further education in allergy and immunology. Our study revealed that the majority of these residents did not feel adequately prepared to treat allergic rhinitis, urticaria, contact dermatitis, antibiotic/drug allergies or anaphylaxis; and only half felt adequately trained to treat asthma. We believe that internal medicine residency programs should provide trainees with additional education in allergy and immunology in order to improve their knowledge and clinical competency. COMMENTARY: DON’T BLOW OFF AR Physicians should help patients with the Rodney Dangerfield of respiratory diseases. BY BARBARA P. YAWN, MD, MSC, FAAFP 6,7 The above article, “Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Training average, greater than that for diabetes. The very common in Internal Medicine Residents,” shines a light on an interesting symptom of nasal congestion affects sleep in people of all issue: Many primary care physicians feel unprepared to address ages, and in children has been shown to interfere with school 8 some of the most common respiratory concerns of patients. -

Update: Virginia Physician Workforce Shortage

UPDATE: VIRGINIA PHYSICIAN WORKFORCE SHORTAGE Joint Commission on Health Care September 17, 2013 Stephen W. Bowman Senior Staff Attorney/Methodologist 2 House Joint Resolution 687 (Del. Purkey) 1. Determine whether a shortage of medical doctors exists in the Commonwealth, by specialty and by geographical region 2. Project the future need for medical doctors in Virginia over the next 10 years by field of specialty 3. Identify and assess factors that contribute to the shortage of medical doctors 4. Identify the medical specialty fields primarily affected by the shortage of doctors 5. Recommend ways to alleviate shortages 1 3 Agenda • Physician Supply, Shortages, and Maldistribution • Medical School Graduates, Residencies, and Geriatric Training • Recent Impacts and State Policies • Policy Options 4 PHYSICIAN SUPPLY, SHORTAGES, AND MALDISTRIBUTION 2 5 Virginia Has Over 16,000 Practicing Physicians and 48% Are Primary Care Providers Specialty Number Percentage Family Medicine 2782 17% General Internal Medicine 2008 12% Pediatric 1744 11% Radiology 1255 8% Obstetrics and Gynecology 1236 8% Psychiatry 1209 7% Other* 6151 38% Total Physicians 16,385 100% *See Appendix for additional breakout of physician specialty counts Primary care specialties are highlighted Source: Virginia Health Chart Book at http://www.vahealthchartbook.org/ and email correspondence with GeoHealth Innovations. 6 46% of Physicians that Manage Patient Load Primary Work Practices Are “Far from Full” Primary Work Location (n= 11,621) 5% Secondary Work Location (n=2,602) 5% Practice is far from full 46% Practice is almost full 36% 49% Practice is full 59% Note: Number and percentage are weighted estimates of physicians that manage patient load from Department of Health Professions Physician Survey Source: Virginia Department of Health Professions, Healthcare Workforce Data Center, Virginia’s Physician Workforce: 2012, July 2013. -

2019‐2020 Internal Medicine Residency Handbook Table of Contents Contacts

2019‐2020 Internal Medicine Residency Handbook Table of Contents Contacts ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Compact ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Core Tenets of Residency ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Program Requirements ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Resident Recruitment/Appointments .............................................................................................. 9 Background Check Policy ................................................................................................................ 10 New Innovations ............................................................................................................................. 11 Social Networking Guidelines ......................................................................................................... 11 Dress Code ...................................................................................................................................... 12 Resident’s Well Being ...................................................................................................................... 13 Academic Conference Attendance ................................................................................................ -

(APC- APM) for Delivering Patient-Centered, Longitudinal, and Coordinated Care

Advanced Primary Care: A Foundational Alternative Payment Model (APC-APM) for Delivering Patient-Centered, Longitudinal, and Coordinated Care A Proposal to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee From the American Academy of Family Physicians April 14, 2017 AAFP Contact: Kent Moore Senior Strategist for Physician Payment American Academy of Family Physicians 11400 Tomahawk Creek Parkway Leawood, KS 66211 Phone: 800-274-2237, extension 4170 Email: [email protected] April 14, 2017 Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee c/o Assistant Secretary of Planning and Evaluation Office of Health Policy U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 200 Independence Avenue S.W. Washington, DC 20201 Proposal – Advanced Primary Care: A Foundational Alternative Payment Model (APC- APM) for Delivering Patient-Centered, Longitudinal, and Coordinated Care Dear PTAC Committee Members: The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) is fully supportive of the Physician- Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee’s (PTAC) role in evaluating physician-focused payment models (PFPMs) and making subsequent recommendations about those models to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The AAFP believes that to be truly successful in improving care and reducing cost, PFPMs and alternative payment models (APMs) need a strong foundation of primary care. Therefore, on behalf of the AAFP, which represents 124,900 family physicians and medical students, I am particularly pleased to submit the following proposal—Advanced Primary Care: A Foundational Alternative Payment Model (APC-APM) for Delivering Patient-Centered, Longitudinal, and Coordinated Care. We request that the PTAC review the model, provide feedback to the AAFP on it, and promptly recommend it to HHS for approval and nationwide expansion. -

ACGME Specialties Requiring a Preliminary Year (As of July 1, 2020) Transitional Year Review Committee

ACGME Specialties Requiring a Preliminary Year (as of July 1, 2020) Transitional Year Review Committee Program Specialty Requirement(s) Requirements for PGY-1 Anesthesiology III.A.2.a).(1); • Residents must have successfully completed 12 months of IV.C.3.-IV.C.3.b); education in fundamental clinical skills in a program accredited by IV.C.4. the ACGME, the American Osteopathic Association (AOA), the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC), or the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC), or in a program with ACGME International (ACGME-I) Advanced Specialty Accreditation. • 12 months of education must provide education in fundamental clinical skills of medicine relevant to anesthesiology o This education does not need to be in first year, but it must be completed before starting the final year. o This education must include at least six months of fundamental clinical skills education caring for inpatients in family medicine, internal medicine, neurology, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, surgery or any surgical specialties, or any combination of these. • During the first 12 months, there must be at least one month (not more than two) each of critical care medicine and emergency medicine. Dermatology III.A.2.a).(1)- • Prior to appointment, residents must have successfully completed a III.A.2.a).(1).(a) broad-based clinical year (PGY-1) in an emergency medicine, family medicine, general surgery, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, or a transitional year program accredited by the ACGME, AOA, RCPSC, CFPC, or ACGME-I (Advanced Specialty Accreditation). • During the first year (PGY-1), elective rotations in dermatology must not exceed a total of two months. -

Supply and Demand of Primary Care Physicians by Region, 2017-2030

Texas Projections of Supply and Demand for Primary Care Physicians and Psychiatrists, 2017 - 2030 As Required by Texas Health and Safety Code Section 105.009 Department of State Health Services July 2018 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ...................................................................................... 3 2. Background ....................................................................................... 5 2.1 Objectives .......................................................................................8 3. Methodology for Supply and Demand Projections .............................. 9 3.1 Supply Model ...................................................................................9 3.2 Demand Model .............................................................................. 10 4. Supply and Demand for Primary Care Physicians ............................ 12 4.1 Supply and Demand for Primary Care Physicians in Texas ................... 12 4.2 Supply and Demand Projections for Primary Care Physicians by Region 15 5. Supply and Demand for Psychiatrists .............................................. 16 5.1 Supply and Demand Projections for Psychiatrists in Texas ................... 16 5.2 Supply and Demand Projections for Psychiatrists by Region ................. 16 6. Strengths and Limitations ............................................................... 18 7. Discussion ...................................................................................... -

Internal Medicine Interest Group Resource Guide

Making the Most of Your Internal Medicine Interest Group: A Practical Resource Guide Developed by the Council of Student Members June 2015 EX4038 Table of Contents Introduction to Internal Medicine Interest Groups................................................................................1 Establishing an IMIG at your School........................................................................................................1 Best Practices for IMIGs ............................................................................................................................3 Holding an Internal Medicine Residency Fair ........................................................................................8 Appendix....................................................................................................................................................9 Introduction to Internal Establishing an IMIG at Your School Medicine Interest Groups You should seek advice from as many resources as possible during the planning An internal medicine interest group (IMIG) is stages. Be sure to consult with your school’s an organized group of medical students who administration about how to establish an meet regularly to learn about internal medi- official club at your school. Once the group’s cine and to establish communication with leadership is established, an e-mail should be faculty and other students who share similar sent out to all group members to poll them interests. IMIGs have a faculty advisor who about activities in which they -

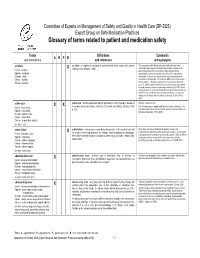

Glossary of Terms Related to Patient and Medication Safety

Committee of Experts on Management of Safety and Quality in Health Care (SP-SQS) Expert Group on Safe Medication Practices Glossary of terms related to patient and medication safety Terms Definitions Comments A R P B and translations and references and synonyms accident accident : an unplanned, unexpected, and undesired event, usually with adverse “For many years safety officials and public health authorities have Xconsequences (Senders, 1994). discouraged use of the word "accident" when it refers to injuries or the French : accident events that produce them. An accident is often understood to be Spanish : accidente unpredictable -a chance occurrence or an "act of God"- and therefore German : Unfall unavoidable. However, most injuries and their precipitating events are Italiano : incidente predictable and preventable. That is why the BMJ has decided to ban the Slovene : nesreča word accident. (…) Purging a common term from our lexicon will not be easy. "Accident" remains entrenched in lay and medical discourse and will no doubt continue to appear in manuscripts submitted to the BMJ. We are asking our editors to be vigilant in detecting and rejecting inappropriate use of the "A" word, and we trust that our readers will keep us on our toes by alerting us to instances when "accidents" slip through.” (Davis & Pless, 2001) active error X X active error : an error associated with the performance of the ‘front-line’ operator of Synonym : sharp-end error French : erreur active a complex system and whose effects are felt almost immediately. (Reason, 1990, This definition has been slightly modified by the Institute of Medicine : “an p.173) error that occurs at the level of the frontline operator and whose effects are Spanish : error activo felt almost immediately.” (Kohn, 2000) German : aktiver Fehler Italiano : errore attivo Slovene : neposredna napaka see also : error active failure active failures : actions or processes during the provision of direct patient care that Since failure is a term not defined in the glossary, its use is not X recommended.