Detailed Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pallas's Cat Status Review & Conservation

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 13 | Spring 2019 Pallas'sCAT cat Status Reviewnews & Conservation Strategy 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser a component of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the Co�chairs IUCN/SSC International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is pu���� Cat Specialist Group lished twice a year, and is availa�le to mem�ers and the Friends of KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, the Cat Group. Switzerland Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] <urs.�[email protected]�e.ch> <ch.�[email protected]> Original contri�utions and short notes a�out wild cats are welcome Send contributions and observations to Associate Editors: Ta�ea Lanz [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are availa�le at www.catsg.org/catnews This Special Issue of CATnews has �een produced with Cover Photo: Camera trap picture of manul in the support from the Taiwan Council of Agriculture's Forestry Bureau, Kot�as Hills, Kazakhstan, 20. July 2016 Fondation Segré, AZA Felid TAG and Zoo Leipzig. (Photo A. Barashkova, I Smelansky, Si�ecocenter) Design: �ar�ara sur�er, werk’sdesign gm�h Layout: Ta�ea Lanz and Christine Breitenmoser Print: Stämpfli AG, Bern, Switzerland ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group The designation of the geographical entities in this pu�lication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or �oundaries. -

Mammalian Predators Appropriating the Refugia of Their Prey

Mamm Res (2015) 60:285–292 DOI 10.1007/s13364-015-0236-y ORIGINAL PAPER When prey provide more than food: mammalian predators appropriating the refugia of their prey William J. Zielinski 1 Received: 30 September 2014 /Accepted: 20 July 2015 /Published online: 31 July 2015 # Mammal Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences, Białowieża, Poland (outside the USA) 2015 Abstract Some mammalian predators acquire both food and predators) may play disproportionately important roles in their shelter from their prey, by eating them and using the refugia communities. the prey construct. I searched the literature for examples of predators that exhibit this behavior and summarize their taxo- Keywords Predator–prey . Dens . Herbivore . Behavior . nomic affiliations, relative sizes, and distributions. I hypothe- Habitat . Resting . Foraging sized that size ratios of species involved in this dynamic would be near 1.0, and that most of these interactions would occur at intermediate and high latitudes. Seventeen species of Introduction Carnivorans exploited at least 23 species of herbivores as food and for their refugia. Most of them (76.4 %) were in the Mammals require food and most require shelter, either to pro- Mustelidae; several small species of canids and a few tect them from predators or from thermal stress. Carnivorous herpestids were exceptions. Surprisingly, the average mammals are unique in that they subsist on mobile food predator/prey weight ratio was 10.51, but few species of pred- sources which, particularly if these sources are vertebrates, ators were more than ten times the weight of the prey whose may build their own refuges to help regulate their body tem- refugia they exploit. -

Pallas's Cat Status Review & Conservation Strategy

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 13 | Spring 2019 Pallas'sCAT cat Status Reviewnews & Conservation Strategy 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser a component of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the Co-chairs IUCN/SSC International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is pub- Cat Specialist Group lished twice a year, and is available to members and the Friends of KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, the Cat Group. Switzerland Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] <[email protected]> <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send contributions and observations to Associate Editors: Tabea Lanz [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with Cover Photo: Camera trap picture of manul in the support from the Taiwan Council of Agriculture's Forestry Bureau, Kotbas Hills, Kazakhstan, 20. July 2016 Fondation Segré, AZA Felid TAG and Zoo Leipzig. (Photo A. Barashkova, I Smelansky, Sibecocenter) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh Layout: Tabea Lanz and Christine Breitenmoser Print: Stämpfli AG, Bern, Switzerland ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Effects of Landscape Change on Corsac Foxes in Mongolia Myagmarjav Lkhagvasuren University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2015 Effects of landscape change on corsac foxes in Mongolia Myagmarjav Lkhagvasuren University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Part of the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons Recommended Citation Lkhagvasuren, Myagmarjav, "Effects of landscape change on corsac foxes in Mongolia" (2015). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 440. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/440 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EFFECTS OF LANDSCAPE CHANGE ON CORSAC FOXES IN MONGOLIA A Thesis Presented by Myagmarjav Lkhagvasuren to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Specializing in Natural Resources October, 2015 Defense Date: June 18, 2015 Thesis Examination Committee: James D. Murdoch, Ph.D., Advisor Laura E. Webb, Ph.D., Chairperson Allan M. Strong, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College ABSTRACT Landscape change affects the distribution of wildlife and represents a conservation concern, especially in Asia, which is experiencing rapid development. In Mongolia, mining, livestock grazing, infrastructure development and climate change represent major drivers of change that will impact habitats and few tools exist to predict how wildlife will respond. I examined the impacts of landscape change on the corsac fox (Vulpes corsac) in a steppe region of Mongolia. -

Den-Site Selection at Multiple Scales by the Red Fox (Vulpes Vulpes Subsp

1 1 Den-site selection at multiple scales by the red fox (Vulpes vulpes subsp. 2 montana) in a patchy human-dominated landscape 3 Muhammad Zaman1#, Bryony A. Tolhurst 2#, Mengyan Zhu1# and Guangshun. Jiang* 4 1 Feline Research Center of National Forestry And Grassland Administration, College of Wildlife And 5 Protected Area , Northeast Forestry University, 26 Hexing Road, Harbin, 150040, China 6 2Ecology, Conservation and Zoonosis Research and Enterprise Group, University of Brighton, 7 Brighton BN2 4GJ, UK 8 #These authors contributed equally to this work. 9 *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 1 2 20 Abstract : Human-wildlife conflict impacts native wildlife populations and people in socio-economically 21 poor areas. In the Shigar Valley, Karakoram range, Pakistan, subsistence mixed farming is the predominant 22 land use and red foxes (Vulpes vulpes montana) are widely persecuted. Knowledge of the effects of human 23 activity on fox behavior and populations in the region is lacking.We carried out 38 transect surveys within 24 87 sampling units of grid size 3km x 3km and recorded 42 resting and 24 active natal dens from 2015 to 25 2017. We evaluated 17 model subsets for describing probabilistic Resource Selection Functions (RSFs) 26 predicting den occurrence at landscape, patch, and micro-habitat scales in terms of anthropogenic factors, 27 including distance to agricultural land and roads. We also tested and controlled for associations between 28 den occurrence and biotic and abiotic variables, including prey occurrence. We found that: 1) distance to 29 roads negatively influenced fox den occurrence; 2) Indian pika (Ochotona roylei) burrow occurrence 30 positively influenced fox den occurrence; (3) Natal dens had larger and more numerous openings than 31 resting dens; 4) den occurrence was greatest at moderate elevations; and 5) den occurrence was negatively 32 related to forest cover and positively correlated with shrub cover. -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

Home Range Characteristics of Corsac and Red Foxes in Mongolia Tserendorjiin Munkhzul Mongolian Academy of Science, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei Institut für Biologie der Martin-Luther-Universität / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Halle-Wittenberg Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298 2012 Home Range Characteristics of Corsac and Red Foxes in Mongolia Tserendorjiin Munkhzul Mongolian Academy of Science, [email protected] J. D. Murdoch University of Vermont R. P. Reading Denver Zoological Foundation Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biolmongol Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Environmental Sciences Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, and the Other Animal Sciences Commons Munkhzul, Tserendorjiin; Murdoch, J. D.; and Reading, R. P., "Home Range Characteristics of Corsac and Red Foxes in Mongolia" (2012). Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298. 12. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biolmongol/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institut für Biologie der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Copyright 2012, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle Wittenberg, Halle (Saale). Used by permission. Erforsch. biol. Ress. Mongolei (Halle/Saale) 2012 (12): 93–104 Home range characteristics of corsac and red foxes in Mongolia T. Munkhzul, J.D. Murdoch, R. Samjaa & R.P. Reading Abstract Red (Vulpes vulpes) and corsac foxes (V. corsac) live sympatrically throughout most of Mongolia, but few details of their home range characteristics exist. -

Report of the Presence of Wild Animals

Report of the Presence of Wild Animals The information recorded here is essential to emergency services personnel so that they may protect themselves and your neighbors, provide for the safety of your animals, ensure the maximum protection and preservation of your property, and provide you with emergency services without unnecessary delay. Every person in New York State, who owns, possesses, or harbors a wild animal, as set forth in General Municipal Law §209-cc, must file this Report annually, on or before April 1, of each year, with the clerk of the city, village or town (if outside a village) where the animal is kept. A list of the common names of animals to be reported is enclosed with this form. Failure to file as required will subject you to penalties under law. A separate Report is required to be filed annually for each address where a wild animal is harbored. Exemptions: Pet dealers, as defined in section 752-a of the General Business Law, zoological facilities and other exhibitors licensed pursuant to U.S. Code Title 7 Chapter 54 Sections 2132, 2133 and 2134, and licensed veterinarians in temporary possession of dangerous dogs, are not required to file this report. Instructions for completing this form: 1. Please print or type all information, using blue or black ink. 2. Fill in the information requested on this page. 3. On the continuation sheets, fill in the information requested for each type of animal that you possess. 4. Return the completed forms to the city, town, or village clerk of each municipality where the animal or animals are owned, possessed or harbored. -

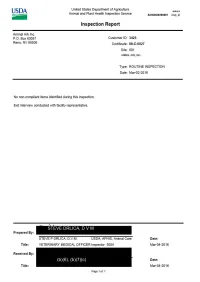

AWA IR C-NV Secure.Pdf

United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 3425 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 02-MAR-16 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 3425 88-C-0027 001 ANIMAL ARK INC. 02-MAR-16 Count Species 000002 Cheetah 000002 Canadian lynx 000001 Jaguar 000001 American badger 000001 Arctic fox 000001 Raccoon 000002 Puma/mountain lion/cougar 000003 North American black bear 000004 Coyote 000000 Tiger 000002 Bobcat 000005 Grey/gray wolf 000002 Red fox 000000 Grey/gray fox 000000 Corsac fox 000001 Kit Fox 000027 Total United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 3425 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 02-MAR-16 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 3425 88-C-0027 001 ANIMAL ARK INC. 02-MAR-16 Count Species 000002 Cheetah 000002 Canadian lynx 000001 Jaguar 000001 American badger 000001 Arctic fox 000001 Raccoon 000002 Puma/mountain lion/cougar 000003 North American black bear 000004 Coyote 000000 Tiger 000002 Bobcat 000005 Grey/gray wolf 000002 Red fox 000000 Grey/gray fox 000000 Corsac fox 000001 Kit Fox 000027 Total United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 3425 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 26-MAR-15 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 3425 88-C-0027 001 ANIMAL ARK INC. 26-MAR-15 Count Species 000002 Cheetah 000003 Canadian lynx 000001 Jaguar 000001 American badger 000001 Arctic fox 000001 Raccoon 000002 Puma/mountain lion/cougar 000002 North American black bear 000002 Coyote 000000 Tiger 000002 Bobcat 000002 Grey/gray wolf 000002 Red fox 000000 Grey/gray fox 000000 Corsac fox 000001 Kit Fox 000022 Total United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 3456 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 03-NOV-14 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 3456 88-C-0074 001 MIRAGE RESORTS INC. -

A Review of Selected Features of the Family Canidae with Reference to Its Fundamental Taxonomic Status Barnabas Pendragon

Papers A review of selected features of the family Canidae with reference to its fundamental taxonomic status Barnabas Pendragon Dogs comprise 35 extant species in 14 genera. They belong to the order Carnivora, which has common morphological and karyotypic features. Within the order, member species can be grouped based on heterologous DNA melting temperatures. The family Canidae forms such a group. Selected features of the Canidae are reviewed here in order to examine the fundamental taxonomic status of this family. Hybrid relationships demonstrate that the family Canidae is a single, reproductively compatible group having the taxonomic status of basic type. As opposed to the various species in the family whose formation was accompanied by genetic change, establishment of the domestic dog was accompanied by almost no genetic change; genetically all domestic dogs are grey wolves. The remarkable variation observed among the various breeds of domestic dog reflects the potential for morphological change hard-wired into the canid genome. The basic type appears to be divided into two subfamilies in the Cenozoic strata; the extant Caninae and the extinct Borophaginae. The ‘oldest’ known canid species is Prohesperocyon, which is found in upper Eocene fossil deposits. Q*HRUJH9HVWD0LVVRXULODZ\HUJDYHXVWKHDGDJH for slicing muscle tissue. However, in the omnivorous I“A dog is a man’s best friend”. More so than any other carnivores such as the bears, true carnassial teeth do not animal, dogs represent friendship and companionship. develop. Nevertheless, dogs, the Canidae, are beasts of prey Interestingly, the carnivore order has a largely belonging to the order Carnivora. They have long slender conservative Karyotype. -

Local Gazetteers Reveal Contrasting Patterns of Historical Distribution

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.15.202390; this version posted August 2, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Local Gazetteers Reveal Contrasting Patterns of Historical Distribution 2 Changes between Apex Predators and Mesopredators in Eastern China 3 Kaijin Hu1, Chunhui Hao2 4 1. School of Sociology and Anthropology, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China 5 2. School of Life Sciences, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China 6 Correspondence author: Kaijin Hu, Email: [email protected] 7 Abstract: 8 Background: Humans have been causing the sixth wave of mass extinction of 9 biodiversity. The situation of predators, especially of carnivores, is a key indicator of 10 biodiversity, and the mesopredator release is a typical phenomenon in ecosystem 11 recess. Local gazetteers( 地 方 志 ) are a rich resource for historical biodiversity 12 research. But there are obvious biases in previous studies focusing in only presence 13 records and neglecting the absence records. We recollected and analyze the records by 14 fixed methods to research historical change of biodiversity. 15 Methods: Innovatively, this research uses both presence and absence records 16 from local gazetteers to reconstruct the distribution of 8 kinds of mammalian 17 predators (i.e. tiger, leopard, bear, wolf, fox, civet, dhole and mustelid) in eastern 18 China from 1573 A.D. to 1949 A.D. (sorted into 4 periods). Then we analyze the 19 distribution changes, the relation between animals and the influence from human. -

Complex Traits: Dogs — a Model for Modern Genetics

GGGGGGGGAAAA TTTTTTGGGGGG GGGTGTTTTTTT TTCTCTCTCCCC AAAAAAAACCCC GGGGGGGGGGGG CCCTCTCCTTTT Complex Traits DogsUsing — Dogs A Model as a Model for for Modern Modern GeneticsGenetics Nancy P. Moreno, Ph.D. CCTCCCCCCCCC GGGGGTGGGTGG AAAAAGAAAGAA CCCCCTCCCTCC GGGGGGGTGGGG TTTTCTTTCTTT AAAAATAAATAA AAAAGAGAGAAA TTTTGTTTGTTT CCCTCTCTCTCC © Baylor College of Medicine CTCTCTTTTTTT GAGAGAGAGGGG GAGAGAGAGGGG SOURCES We are grateful to the following individuals and institutions for generously providing us with permission to use their images and source materials in this publication. Pages 1–3: California Department of Fish and Wildlife. © 2017 by Baylor College of Medicine. All rights reserved. Distinguishing between Coyotes, Wolves and Dogs. Printed in the United States of America. Track patterns by Karen Converse. https://www. ISBN: 978-1-944035-08-2 wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Mammals/Gray-Wolf/ Identification Page 4: Wayne, R., and Ostrander, E. Lessons learned from the dog genome. TRENDS in Genetics. 23 (2007): 557-567. Licensed for use March 2, 2016: Elsevier and Copyright Clearance Center: License Number Teacher Resources from the Center for Educational Outreach at Baylor College of Medicine. 3820930088090. http://www.sciencedirect.com/ science/article/pii/S0168952507003058# The mark “BioEd” is a service mark of Baylor College of Medicine. Page 5: African wild dog © Michael Gäbler, Wikimedia Commons CC-BY-SA 3.0. Dog (boxer) © Artman1, Development of Complex Traits educational materials was supported, in part, by a grant from licensed for use. Gray wolf © MacNeil Lyons, courtesy the Science Education Partnership Award Program Office of the Director, National Institutes of of the U.S. National Park Service. Arctic fox © Jason Health grant 5R25OD011134 (Principal Investigator, Nancy Moreno, Ph.D.). Activities described in Burrows; Bat-eared fox © Mike Cilliers; Black-backed this book are intended for middle school students under direct supervision of adults.