Riparian Bird Communities of the Great Plains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nebraska Department of Education Nebraska Education Directory 104 Edition 2001-2002 Table of Contents

NEBRASKA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION NEBRASKA EDUCATION DIRECTORY 104th EDITION 2001-2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Please note: The following documents are not inclusive to what is in the published copy of NDE’s Education Directory. Page numbers in the document will appear as they do in the published directory. Please use the bookmarks for fast access to the information you require (turn on “show/hide navigation pane” button on the toolbar in Adobe). PART I: GENERAL INFORMATION Nebraska Teacher Locator System.................................................................(2) Nebraska Department of Education Services Directory...............................(3-6) Nebraska Department of Education Staff Directory.......................................(7-11) Job Position and Assignment Abbreviations..................................................(12-13) PART II: EDUCATIONAL SERVICE UNITS Educational Service Units.................................................................................(14-17) PART III: PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICTS IN NEBRASKA Index of Nebraska Public School Districts by Community.............................(18-26) School District Dissolutions and Unified Interlocal Agreements...................(27) Alphabetical Listing of All Class 1 through 6 School District.........................(28-152) PART IV: NONPUBLIC SCHOOLS IN NEBRASKA Nonpublic School System Area Superintendents...........................................(153) Index of Nebraska NonPublic School Systems by Name..............................(154-155) Alphabetical Listing -

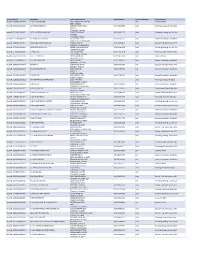

Contractor List

Active Licenses DBA Name Full Primary Address Work Phone # Licensee Category SIC Description buslicBL‐3205002/ 28/2020 1 ON 1 TECHNOLOGY 417 S ASSOCIATED RD #185 cntr Electrical Work BREA CA 92821 buslicBL‐1684702/ 28/2020 1ST CHOICE ROOFING 1645 SEPULVEDA BLVD (310) 251‐8662 subc Roofing, Siding, and Sheet Met UNIT 11 TORRANCE CA 90501 buslicBL‐3214602/ 28/2021 1ST CLASS MECHANICAL INC 5505 STEVENS WAY (619) 560‐1773 subc Plumbing, Heating, and Air‐Con #741996 SAN DIEGO CA 92114 buslicBL‐1617902/ 28/2021 2‐H CONSTRUCTION, INC 2651 WALNUT AVE (562) 424‐5567 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia SIGNAL HILL CA 90755‐1830 buslicBL‐3086102/ 28/2021 200 PSI FIRE PROTECTION CO 15901 S MAIN ST (213) 763‐0612 subc Special Trade Contractors, NEC GARDENA CA 90248‐2550 buslicBL‐0778402/ 28/2021 20TH CENTURY AIR, INC. 6695 E CANYON HILLS RD (714) 514‐9426 subc Plumbing, Heating, and Air‐Con ANAHEIM CA 92807 buslicBL‐2778302/ 28/2020 3 A ROOFING 762 HUDSON AVE (714) 785‐7378 subc Roofing, Siding, and Sheet Met COSTA MESA CA 92626 buslicBL‐2864402/ 28/2018 3 N 1 ELECTRIC INC 2051 S BAKER AVE (909) 287‐9468 cntr Electrical Work ONTARIO CA 91761 buslicBL‐3137402/ 28/2021 365 CONSTRUCTION 84 MERIDIAN ST (626) 599‐2002 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia IRWINDALE CA 91010 buslicBL‐3096502/ 28/2019 3M POOLS 1094 DOUGLASS DR (909) 630‐4300 cntr Special Trade Contractors, NEC POMONA CA 91768 buslicBL‐3104202/ 28/2019 5M CONTRACTING INC 2691 DOW AVE (714) 730‐6760 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia UNIT C‐2 TUSTIN CA 92780 buslicBL‐2201302/ 28/2020 7 STAR TECH 2047 LOMITA BLVD (310) 528‐8191 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia LOMITA CA 90717 buslicBL‐3156502/ 28/2019 777 PAINTING & CONSTRUCTION 1027 4TH AVE subc Painting and Paper Hanging LOS ANGELES CA 90019 buslicBL‐1920202/ 28/2020 A & A DOOR 10519 MEADOW RD (213) 703‐8240 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia NORWALK CA 90650‐8010 buslicBL‐2285002/ 28/2021 A & A HENINS, INC. -

GEODETIC SURVEYS in the UNITED STATES the BEGINNING and the NEXT ONE HUNDRED YEARS 1807Ана1940 Joseph F. Drac

5/28/2017 Geodetic Surveys GEODETIC SURVEYS IN THE UNITED STATES THE BEGINNING AND THE NEXT ONE HUNDRED YEARS 1807 1940 Joseph F. Dracup Coast and Geodetic Survey (Retired) 12934 Desert Glen Drive Sun City West, AZ 853754825 ABSTRACT The United States began geodetic surveys later than most of the world's major countries, yet its achievements in this scientific area are immense and unequaled elsewhere. Most of the work was done by a single agency that began as the Survey of the Coast in 1807, identified as the Coast Survey in 1836,renamed the Coast and Geodetic Survey in 1878 and since about 1970 the National Geodetic Survey, presently an office in the National Ocean Service, NOAA. An introduction containing a brief history of geodetic surveying to 1800 is followed by accounts of the American experience to 1940. Broadly speaking the 18071940 period is divided into three sections: The Early Years 18071843, Laying the Foundations of the Networks 18431900 and Building the Networks 19001940. The scientific accomplishments, technology developments, major and other interesting events, anecdotes and the contributions made by the people of each period are summarized. PROLOGUE Early Geodetic Surveys And The BritishFrench Controversy The first geodetic survey of note was observed in France during the latter part of the 17th and early 18th centuries and immediately created a major controversy. Jean Picard began an arc of triangulation near Paris in 166970 and continued the work southward until his death about 1683. His work was resumed by the Cassini family in 1700 and completed to the Pyrenees on the Spanish border prior to 1718 when the northern extension to Dunkirk on the English Channel was undertaken. -

Ecology and Management of Morels Harvested from the Forests of Western North America

United States Department of Ecology and Management of Agriculture Morels Harvested From the Forests Forest Service of Western North America Pacific Northwest Research Station David Pilz, Rebecca McLain, Susan Alexander, Luis Villarreal-Ruiz, General Technical Shannon Berch, Tricia L. Wurtz, Catherine G. Parks, Erika McFarlane, Report PNW-GTR-710 Blaze Baker, Randy Molina, and Jane E. Smith March 2007 Authors David Pilz is an affiliate faculty member, Department of Forest Science, Oregon State University, 321 Richardson Hall, Corvallis, OR 97331-5752; Rebecca McLain is a senior policy analyst, Institute for Culture and Ecology, P.O. Box 6688, Port- land, OR 97228-6688; Susan Alexander is the regional economist, U.S. Depart- ment of Agriculture, Forest Service, Alaska Region, P.O. Box 21628, Juneau, AK 99802-1628; Luis Villarreal-Ruiz is an associate professor and researcher, Colegio de Postgraduados, Postgrado en Recursos Genéticos y Productividad-Genética, Montecillo Campus, Km. 36.5 Carr., México-Texcoco 56230, Estado de México; Shannon Berch is a forest soils ecologist, British Columbia Ministry of Forests, P.O. Box 9536 Stn. Prov. Govt., Victoria, BC V8W9C4, Canada; Tricia L. Wurtz is a research ecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Boreal Ecology Cooperative Research Unit, Box 756780, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK 99775-6780; Catherine G. Parks is a research plant ecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forestry and Range Sciences Laboratory, 1401 Gekeler Lane, La Grande, OR 97850-3368; Erika McFarlane is an independent contractor, 5801 28th Ave. NW, Seattle, WA 98107; Blaze Baker is a botanist, U.S. -

The Ornithogeography of the Great Plains States

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 12-1978 The Ornithogeography of the Great Plains States Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The Ornithogeography of the Great Plains States" (1978). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 44. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/44 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Johnsgard in Prairie Naturalist (December 1978) 10(4). Copyright 1978, North Dakota Natural Science Society. Used by permission. The Ornithogeography of the Great Plains States Paul A. Johnsgard School of Life Sciences University of Nebraska Lincoln, Nebraska 68588 INTRODUCTION It has long been recognized that the Great Plains represent a major transition zone in the distribution patterns of North American birds; field guides traditionally have treated the 100° W.longitude meridian as a convenient dividing line between eastern and western faunas. Furthermore, this line rather neatly bisects the political subdivisions of the Great Plains, namely the "plains states" extending from North Dakota southward through South Dakota, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Texas. Of these, Texas is the least typical, its climate and fauna is strongly influenced by the Gulf Coast on the east and the Chihuahuan desert on the west. As a result of its size and ecological diversity Texas supports the largest array of breeding bird species of any state in the nation. -

Tonopah Westercon Program Book

Westercon 65 Program Book “It’s a Blast!” July 5-8, 2012 ● Tonopah NV Westercon 65 The 65th West Coast Science Fantasy Conference Tonopah Station Hotel, Tonopah NV Thursday, July 5 – Monday, July 8, 2012 Guest of Honor Fluff the Plush Cthulhu Committee List Chairman: Kevin Standlee Newsletter: Scott Sanford Vice Chair: Kuma Bear Guest Liaison: Kuma Bear Hotel/Facilities Liaison: Business Meeting: Kevin Lisa Hayes Standlee Programming: Bobbie DuFault BM Secretary: Linda Deneroff Dealers Room: David W. Clark Site Selection: Glenn Glazer Hospitality: Sandra Childress Gaming: Tom Galloway Masquerade: John Blaker Logistics: Christian McGuire Operations: Randy Smith Sales to Members: Fanzine Lounge: Chris Garcia Scott Dennis ©2012 Nevada Association for Scientificional Activities, PO Box 242, Fernley NV 89408, with all applicable rights reverting to contributors upon publication. “Westercon” is a registered service mark of the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Soci- ety, Inc. <http://www.lasfs.info/>. Westercon 65 Westercon 65 which were on the ballot may be selected. A site chosen under the provisions of this Greetings from the Chairman section shall not be restricted by any portion of this article except this section and sec- tion 3.1. Kevin Standlee 3.17 Availability of Results Welcome to Tonopah! When the Westercon Business The results of the balloting shall be reported to the site-selection business meeting of Meeting in Pasadena two years ago voted to award the administering Westercon, if one is held. A record of the results of the balloting, Westercon 65 to the committee headed by my wife’s including all intermediate counts and distinguishing between the by-mail and at-con stuffed bear, you can imagine that I was wondering what ballots, shall be published in the first or second progress report of the winning Wester- we were going to do. -

MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW Editor, EDGAR W

MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW Editor, EDGAR W. WOOLARD ____._. ~- VOL. 64, No. 6 CLOSEDAUGUST 3, 1936 W. B. No. 1185 JUNE 1936 ISSUEDSEPTEMBER 15,1936 DUSTSTORMS IN THE SOUTHWESTERN PLAINS AREA By H. F. CHOTJN [Weather Bureau, Denver, Colo., April 19361 Numerous articles, and photographs which apparently period of a normal year. The diurnal range in the wind substantiate them, have in the recent past predicted thn.t movement is large, the velocities being generally higb in either large acreages of land in the dust-bowl area of the the afternoon and dying down at night. Chinook winds southwestern plains must be abandoned, or else continued prevail td a great extent throughout the area, causin depression and failure must be faced by those trying to large daily range in temperature. Occasional dry speHa Is, combat the elements. This paper, while it will verify and periods of abnormally heavy precipitation, persist the seriousness and severity of soil erosion due to wind in over periods of 2 or 3 years with resulting serious droughts the area shown in figure 1, will also show that total and great variations in crop yields. The question of abandonme,nt of the area is not imminent or necessary. whether there has been any progressive 3r retrogressive change in the amount of precipitation since the Plains area was settled, has been the subject of much discussion. The esamination of reliable precipitation records, same of which were begun more than 50 years ago, bears out the view that no appreciable permanent change has taken place that will greatly afl’ect the normal. -

Side Shots 8-08

August 2008 Professional Land Surveyors of Colorado Volume 39, Issue 3 Fall Technical Conference University of Denver November 13-15, 2008 Inside: “It’s All in the Meridian” - page 5 “Surveying Slump?” - page 7 Report from the State Board of Licensure - page 13 PROFESSIONAL LAND SURVEYORS OF COLORADO, INC. P.O. Box 704, Conifer, CO 80433 AFFILIATE - NATIONAL SOCIETY OF PROFESSIONAL SURVEYORS MEMBER - COLORADO ENGINEERING COUNCIL MEMBER- WESTERN FEDERATION OF PROFESSIONAL SURVEYORS OFFICERS (2007-2008) TOM T. ADAMS JOHN B. GUYTON GENE KOOPER DIANA E. ASKEW VICE PRESIDENT PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR SECRETARY-TREASURER 1210 24TH LANE WFPS DELEGATE 8151 W. EVANS AVE. 12322 S. WAMBLEE VALLEY RD PUEBLO, CO 81006 FLATIRONS, INC. LAKEWOOD, CO 80227 CONIFER, CO 80433 H: (719) 296-8262 3825 IRIS AVENUE, STE. 395 O: (303) 989-5424 H: (303) 838-7577 O: (719) 546-5454 BOULDER, CO 80301 F: (303) 989-5598 O: (720) 946-0969 F: (719) 546-5410 O: (303) 443-7001 F: (720) 946-0973 F: (303) 443-9830 DIRECTORS (2005-2008) Dear Fellow Members, LAWRENCE T. CONNOLLY In my previous letter, I pointed out the necessity of spreading the word about the bene- 29210 HIGHWAY 160, UNIT D DURANGO, CO 81303 fits of PLSC membership to non-members, to increase support for our professional H; (970) 759-4477 O: (970) 385-6891 organization during these difficult economic times. F: (970) 385-6295 I am pleased to report that some real progress is being made. Either my pleas for LES E. DOEHLING delinquent members to pay their annual dues, or a large mailing of reminder notices, or 3124 AMERICANA DRIVE GRAND JUNCTION, CO 81504 both, had some effect. -

September 1991

SEPTEMBER 1991 /•*> "...she appeared in a skimpy black skirt brandishing a whip. She toned down her dress later to try to escape the lunatic ^e#" The Province. 1991. to be continued. HOTTEST TOP 40 c STARTS A DANCE CLUB U o G U s THROW A V T PARTY, 1991 FUNDRAISER, OR CORPORATE PARTY, ITSFREE E CALL US. LA ORIGINAL R IDEAS HAPPEN AT IF YOU MISSED TOE CHANCE TO ENJOY ^ FREE COVER, CALL US FOR A FREE PASS. d DON'T MISS OUT THIS TIME 876 315 BROADWAY at KINGSWAY v70©3, OPEN s 8 PM TO 2 AM - TUE. to SAT. SUNDAYS to MIDNIGHT COWSHEAD CHRONICLES byGTH MX FATHER \MJ 1 1 SID IO XIXKE CHOI OLATF SUCK DiSfcOBPEK FRI >M SCR VI 111 I SIM; COCOA. fca^fc: BLAH...RENT,' Mil K.omi kSIR wm INGRE DIENTS \M) \ SIOU, ||()| Ilk IIIXN mi in its oi in II . n SI I.MS NOW III \l Wl REPEAT- ID mis si NDXX NIGIII IR xm mmxak BLAH...TUITDN, HON Ol UN HI 1 I'M AIR XII) AUGUST 1991 - ISSUE #104... ni vi n XSKEDNOW IOKEPLI- i \n i ins si IXHNGLX SIMPLE RECIPI IDHXVEIOPHONETHE Hit; lil X FOR SOXH MIT1 HY BOOKS, BLAH... Sill' INSIkU IIONS. 1 IIXVE. IRREGULARS HOWEVER. NO WISDOM kE- i; XKDINI; x vol M; VIAVS kin s oi PXSSXGF \ND THE WOMEN OF THE FOLK FEST XlXMNIi Ol CHOCOLATE su ci: HI 1 SOMI.ruiNi; IN Ilkl.l.X Dill 1 KIM Ill\l IS1 P- DOING DRUGS IN PUBLIC POSE DOI s | IGl kl IN MY IV The How To (or not how to) 10 mi k XNDOIIII RSTIIXISIIXLL FOR till ll\ll HI INC Will RE- HELP!!! M \IN NXM1 I I.SSBl 1 I'M si KI; Back Alley Fiction 11 1111 \l.l. -

Introduction to Solar Geometry

1 Solar Geometry The Earth’s daily rotation about the axis through its two celestial poles (North and South) is perpendicular to the equator, but it is not perpendicular to the plane of the Earth’s orbit. In fact, the measure of tilt or obliquity of the Earth’s axis to a line perpendicular to the plane of its orbit is currently about 23.5°. We call the plane parallel to the Earth’s celestial equator and through the center of the sun the plane of the Sun. The Earth passes alternately above and below this plane making one complete elliptic cycle every year. Dennis Nilsson [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)] Winter Solstice (z Dec 21) Vernal Equinox (z March 21 ) SUN P L A N E O F S U N Autumnal Equinox (z Sept 23) Summer Solstice (z June 21 ) 2 Summer Solstice On the occasion of the summer solstice, the Sun shines down most directly on the Tropic of Cancer in the northern hemisphere, making an angle δ = +23.5° with the equatorial plane. We call δ the Sun declination angle. In general, the Sun declination angle, δ, is defined to be that angle made between a ray of the Sun, when extended to the center of the earth, O, and the equatorial plane. We take δ to be positively oriented whenever the Sun’s rays reach O by passing through the Northern hemisphere. On the day of the summer solstice, the sun is above the horizon for the longest period of time in the northern hemisphere. -

Western Burrowing Owl in the United States Biological Technical Publication BTP-R6001-2003 © Michael Forsberg

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Status Assessment and Conservation Plan for the Western Burrowing Owl in the United States Biological Technical Publication BTP-R6001-2003 © Michael Forsberg U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Status Assessment and Conservation Plan for the Western Burrowing Owl in the United States Biological Technical Publication BTP-R6001-2003 David S. Klute1,7 William H. Howe4 Steven R. Sheffield6,9 Loren W. Ayers2,8 Stephanie L. Jones1 Tara S. Zimmerman3 Michael T. Green3 Jill A. Shaffer5 1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6, Nongame Migratory Bird Program, Denver, CO 2 Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 3 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 1, Nongame Migratory Bird Program, Portland, OR 4 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 2, Nongame Migratory Bird Program, Albuquerque, NM 5 U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Jamestown, ND 6 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Migratory Bird Management, Arlington, VA 7 Current Address: Colorado Division of Natural Resources 8 Current Address: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources 9 Current Address: George Mason University Author contact information: For additional copies or information, contact: Nongame Migratory Bird Program David S. Klute, (Current address) Colorado Division U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service of Wildlife, 6060 Broadway, Denver, CO 80216. P.O. Box 25486 DFC Phone: (303) 291-7320, Fax: (303) 291-7456, Denver, CO 80225-0486 e-mail: [email protected]. Recommended citation: Loren W. Ayers, (Current address) Bureau of Klute, D. S., L. W. Ayers, M. T. Green, W. -

Mapping Nebraska, 1866-1871: County Boundaries, Real and Imagined

Mapping Nebraska, 1866-1871: County Boundaries, Real and Imagined (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Brian P Croft, “Mapping Nebraska, 1866-1871: County Boundaries, Real and Imagined,” Nebraska History 95 (2014): 230-245 Article Summary: How is it that six nonexistent western Nebraska counties could appear on maps in 1866 and remain on virtually all territorial and state maps for nearly a decade? The story of how this happened reveals the evolving process of county formation during Nebraska’s transition to statehood, and also shows how publishers of maps gathered information about the development of remote areas. Cataloging Information: Names: G W and C B Colton, Augustus F Harvey, Alvin Saunders, Rufus Blanchard Nonexistent Nebraska Counties Shown on Maps: Lyon, Taylor, Monroe, Harrison, Jackson, Grant Keywords: H.R. 104, Twelfth Territorial Session, 1867 (unsigned); S. No. 6, 1867; S. No 11, 1867; 1870 census; Kansas-Nebraska Act; G W and C B Colton and Company; Colton’s Township Map of the