The Ecstatic Geography of Walt Whitman and Frank Lloyd Wright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Looking for Usonia : Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's Post-1935 Residential Designs As Generators of Cultural Landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University

Masthead Logo Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2006 Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Brown, William Randall, "Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes" (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 18982. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/18982 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes by William Randall Brown A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Architectural Studies Program of Study Committee: Arvid Osterberg, Major Professor Daniel Naegele Karen Quance Jeske Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright ©William Randall Brown, 2006. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate C of I ege Iowa State University This i s to certify that the master' s thesis of V~illiam Randall Brown has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University :atures have been redact` 111 LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The state of Usonia 8 A brief history of Usonia 9 The evolution of Usonian design 13 Preserving Usonia 19 Toward a cultural landscape 21 METHODOLOGY 26 CASE STUDIES: HOUSE MUSEUMS ON PRIVATE LAND No. -

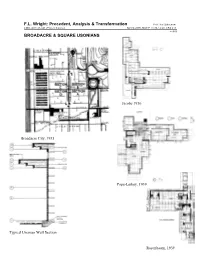

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C. -

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Frank_... Frank Lloyd Wright From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Frank Lloyd Wright (born Frank Lincoln Wright, June 8, 1867 – April 9, Frank Lloyd Wright 1959) was an American architect, interior designer, writer and educator, who designed more than 1000 structures and completed 532 works. Wright believed in designing structures which were in harmony with humanity and its environment, a philosophy he called organic architecture. This philosophy was best exemplified by his design for Fallingwater (1935), which has been called "the best all-time work of American architecture".[1] Wright was a leader of the Prairie School movement of architecture and developed the concept of the Usonian home, his unique vision for urban planning in the United States. His work includes original and innovative examples of many different building types, including offices, churches, schools, Born Frank Lincoln Wright skyscrapers, hotels, and museums. Wright June 8, 1867 also designed many of the interior Richland Center, Wisconsin elements of his buildings, such as the furniture and stained glass. Wright Died April 9, 1959 (aged 91) authored 20 books and many articles and Phoenix, Arizona was a popular lecturer in the United Nationality American States and in Europe. His colorful Alma mater University of Wisconsin- personal life often made headlines, most Madison notably for the 1914 fire and murders at his Taliesin studio. Already well known Buildings Fallingwater during his lifetime, Wright was recognized Solomon R. Guggenheim in 1991 by the American Institute of Museum Architects as "the greatest American Johnson Wax Headquarters [1] architect of all time." Taliesin Taliesin West Robie House Contents Imperial Hotel, Tokyo Darwin D. -

Communities by Design in THIS ISSUE

EDUCATION | ADVOCACY | PRESERVATION THE MAGAZINE OF THE FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BUILDING CONSERVANCY THE MAGAZINE OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BUILDING CONSERVANCY FALL 2016 / VOLUME 7 ISSUE 2 FALL IN THIS ISSUE Communities by Design Guest Editor: Jane King Hession editor’s MESSAGE communities by design Communities can take many forms and mean different things to different people. Vary though they may, all communities are fundamentally alike in that they are all composed of individuals who, col- lectively, share common interests, characteristics or geography. The whole of a community comprises its parts. Frank Lloyd Wright was no stranger to this concept: for decades he lived and worked at the center of the Taliesin Fellowship, a community of his own creation. However, as the essays in this issue make clear, Wright also explored the idea of community—at multiple scales—in his architecture and planning. In his article on the politics of community, Robert Wojtowicz considers the philosophical divide between Wright and his longtime friend (and sometime foe), cultural critic Lewis Mumford, on the subject. As Wojtowicz describes, the two men often argued their polar positions on the pages of the country’s leading publications. The roots of one of Wright’s best known communities, Usonia in Pleasantville, New York, are revisited by an original owner in the community, Roland Reisley. In ad- ABOUT THE EDITOR dition to taking a backward glance at its origins, Reisley also reveals the impact of Wright’s vision on successive generations of residents. Neil Levine describes Wright’s application of “the power of ge- ometry” to create community at the scale of the individual house and the residential block. -

Save the Date Wright & Like 2012

VOLUME 17 ISSUE 1 FEBRUARY 2012 n NEWSLETTER OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT® WISCONSIN n SC Johnson Conserves FLLW Artifacts by Mark Hertzberg Seventy-five years after H. F. Johnson, Jr. met Frank Lloyd Wright and hired him to design his company’s new office building, Johnson’s grandson Fisk and the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation have announced a 99-year loan agreement between SC Johnson and the Foundation for 60 artifacts from the Foundation’s archives. The loan grew out of discussions after the Foundation applied for a grant from the SC Johnson Fund for a fire suppression system for the archives at Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona and explored ways to raise money for a building to house the archives. Last year Wright bloggers expressed concern about rumors that the archives might be sold to private interests and no longer be accessible to researchers. The Johnson loan agreement not only helps ensure the preservation of the artifacts, some of which are not stored in optimal conditions, but also makes them available to the public. SC Johnson will conserve the artifacts including china, a hanging lamp and windows from the Heath House in Frank Lloyd Wright and H. F. Johnson, Jr. Buffalo (1905), a wooden armchair from Taliesin West Photo Credit: Courtesy SC Johnson (1946), a slant-back dining room chair from the Hillside outside the SC Johnson Research Tower. Home School (1902), a reception chair from Wright’s Oak Park studio (1895), carpets, and a grand piano that The Johnson exhibition will focus on Wright’s influence belonged to one of Wright’s sisters. -

The Architecture of Local Performance: Stages of the Taliesin Fellowship

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre (JADT) https://jadtjournal.org The Architecture of Local Performance: Stages of the Taliesin Fellowship by Claudia Wilsch Case The Journal of American Drama and Theatre Volume 32, Number 2 (Spring 2020) ISNN 2376-4236 ©2020 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center During the Great Depression, architect Frank Lloyd Wright founded the Taliesin Fellowship, an apprenticeship program for students of architecture and related trades that valued physical labor as an educational tool. Based at Wright’s family home and the adjacent former Hillside Home School in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and later expanding to Taliesin West near Scottsdale, Arizona, the Fellowship offered tuition-paying students a hands-on alternative to a college education by conveying Wright’s theory of organic architecture through practical experience. Echoing certain aspects of the British and American Arts and Crafts movements, the German Bauhaus, and the Eastern mystic Georges Gurdjieff’s Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, the Taliesin Fellowship was an experiment in communal work, living, and learning. Like the collectives that inspired it, the Taliesin Fellowship engaged its members in a variety of artistic pursuits, and its amateur performing arts activities became cherished entertainment for local audiences. Beginning with apprentice-staged concerts, skits, and film screenings in the 1930s and presenting Gurdjieff-inspired physical movements in the 1950s, the Fellowship’s performances by the 1960s culminated in original dance dramas, written and choreographed by Wright’s daughter, Iovanna Lloyd Wright. Taking inspiration from Gurdjieff’s philosophy and from her father’s architectural concepts, Iovanna’s work, though created in isolation, echoes aspects of the physical culture movement and connects with twentieth-century expressive dance. -

Protecting Usonia a Homeowner’S and Site Manager’S Resource for Understanding and Addressing Common Preservation Concerns in Frank Lloyd Wright’S Usonian Home

PROTECTING USONIA A HOMEOWNER’S AND SITE MANAGER’S RESOURCE FOR UNDERSTANDING AND ADDRESSING COMMON PRESERVATION CONCERNS IN FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT’S USONIAN HOME A THESIS SUBMITTED ON THE 29TH DAY OF APRIL 2018 TO THE DEPARTMENT OF PRESERVATION STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE OF TULANE UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PRESERVATION STUDIES BY EMILY BUTLER APPROVED: __________________ Professor John Stubbs Director 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Personal Statement……………………..………………………………………………………………………………..3 Primary Goals…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 Methodology………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….7 Chapter 2 Understanding Wright……………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Historical Background…………………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Organic Architecture As Described By Wright……………………………………………………………….13 Usonia: Concept to Reality……………………………………………………………………………………………16 Usonian Forms: Module and Unit System…………………………………………………………………….25 Common Building Materials and Elements……………………………………………………………………30 A Note on Sustainability……………………………………………………………………………………………….32 Chapter 3 Case Studies in Preserving Usonian Homes………………………………………………………………33 Case Study: Herbert Jacobs House……………………………………………………………..…………………33 Case Study: Kentuck Knob – I.N. & Bernardine Hagan House………………………………………..40 Case Study: Rosenbaum House…………………………………………………………………………………….57 Case Study: Pope-Leighey House………………………………………………………………………………….66 Chapter 4 Homeowners -

2018 Member Newsletter Celebrating the Legacy of Frank Lloyd Wright

Volume 23 Issue 3 SEPTEMBER 2018 MEMBER NEWSLETTER CELEBRATING THE LEGACY OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT Retreat to Delavan Lake A FRESH LOOK AT THE HENRY H. WALLIS SUMMER COTTAGE page 8 © Mark Hertzberg © Mark Welcome Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy Wright in Wisconsin is excited to wel- The FLWBC’s mission is focused exclu- While our mission shares the FLWBC’s come the Frank Lloyd Wright Building sively on the preservation and mainte- commitment to preserving Wright’s President’s Message Conservancy (FLWBC) back to Wiscon- nance of all of Wright’s remaining work (e.g., our restoration of Wright’s by MICHAEL DITMER sin. This will be the second time the buildings. Simply put, the group works American System-Built homes in Mil- group has held its annual event at the to “save Wright” through a mix of educa- waukee), we also are committed to pro- Monona Terrace Community and Con- tion, advocacy and technical services. To mote Wright’s legacy and that of his vention Center in Madison. this end, the FLWBC has worked on apprentices in his home state. Our most more than 100 cases involving Wright recent success in that area was the crea- Members of our board of directors have buildings across the country. tion of the Frank Lloyd Wright Trail. been working with the FLWBC staff and volunteers for many months to assist in It truly is a nationwide, even worldwide, There is no richer landscape in which to “So here I stand before you preaching or- I have come convinced the future is in good hands. -

Frank Lloyd Wright Architectural Drawing

CLIENT NAME PROJECT NO. ITEM COUNT PROJECT TITLE WORK TYPE CITY STATE DATE Ablin, Dr. George Project 5812 19 drawings Dr. George Ablin house (Bakersfield, California). House Bakersfield CA 1958 Abraham Lincoln Center Project 0010 53 drawings Abraham Lincoln Center (Chicago, Illinois). Unbuilt Project Religious Chicago IL 1900 Achuff, Harold and Thomas Carroll Project 5001 21 drawings Harold Achuff and Thomas Carroll houses (Wauwatosa, Wisconsin). Unbuilt Projects Houses Wauwatosa WI 1949 Ackerman, Lee, and Associates Project 5221 7 drawings Paradise on Wheels Trailer Park for Lee Ackerman and Associates (Paradise Valley, Arizona). Trailer Park (Paradise on Wheels) Phoenix AZ 1952 Unbuilt Project Adams, Harry Project 1105 45 drawings Harry Adams house (Oak Park, Illinois). House Oak Park IL 1912 Adams, Harry Project 1301 no drawings Harry Adams house (Oak Park, Illinois). House Oak Park IL 1913 Adams, Lee Project 5701 11 drawings Lee Adams house (Saint Paul, Minnesota). Unbuilt Project House St. Paul MN 1956 Adams, M.H. Project 0524 1 drawing M. H. Adams house (Highland Park, Illinois). Alterations, Unbuilt Project House, alterations Highland Park IL 1905 Adams, Mary M.W. Project 0501 12 drawings Mary M. W. Adams house (Highland Park, Illinois). House Highland Park IL 1905 Adams, William and Jesse Project 0001 no drawings William and Jesse Adams house (Oak Park, Illinois). House Chicago IL 1900 Adams, William and Jesse Project 0011 4 drawings William and Jesse Adams house (Oak Park, Illinois). House Longwood IL 1900 Adelman, Albert Project 4801 47 drawings Albert Adelman house (Fox Point, Wisconsin). Scheme 1, Unbuilt Project House (Scheme 1) Fox Point WI 1946 Adelman, Albert Project 4834 31 drawings Albert Adelman house (Fox Point, Wisconsin). -

Authenticity and the Popular Appeal of Frank Lloyd Wright Daniel J

Architecture Publications Architecture 2008 Authenticity and the popular appeal of Frank Lloyd Wright Daniel J. Naegele Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ arch_pubs/36. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authenticity and the popular appeal of Frank Lloyd Wright Abstract The inside cover of the January 17,1938 Life magazine featured a photograph of the recently completed Kaufmann weekend house,'Fallingwater,' designed by America's best known architect, the then 70-year-old Frank Lloyd Wright: The house is shown emerging from thick woods, hovering above flowing water.The view is not from the approach to the house or from within, but from the outside, downstream, a vantage point that renders the conceptual idea of the house in its entirety: the magic of immense heaviness levitating; the Biblical metaphor of water from rock; an exclusive retreat alone in acres of wooded paradise. Disciplines Architectural History and Criticism Comments This chapter is from Amerikaanse dromen Frank Lloyd Wright en Nederland, ed. Herman van Bergeijk (Rotterdam: Uitgeverij 010, 2008). -

BROADACRE CITY: AMERICAN FABLE and TECHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY by WILLIAMR SHAW a THESIS Presented to the Department of Architecture A

BROADACRE CITY: AMERICAN FABLE AND TECHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY by WILLIAMR SHAW A THESIS Presented to the Department ofArchitecture and the Graduate School ofthe University of Oregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArchitecture December 2009 11 "Broadacre City: American Fable and Technological Society," a thesis prepared by William R Shaw in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master ofArchitecture degree in the Department ofArchitecture. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: Date Committee in Charge: Alison Snyder, Chair James Tice Deborah Hurtt Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School 111 © 2009 William R Shaw IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of William R Shaw for the degree of Master ofArchitecture in the Department ofArchitecture to be taken December 2009 Title: BROADACRE CITY: AMERICAN FABLE AND TECHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY Approved: -- yder In the 1930s Frank Lloyd Wright began working on a plan to remake the architectural fabric ofthe United States. Based on the principle ofdecentralization, Wright advocated for the abandonment ofthe industrialized city in favor ofan agrarian landscape where each individual would have access to his or her own acre ofland. Wright's vision, which he called Broadacre City, was to be the fruit ofmodem technology directed towards its proper end - human freedom. Envisioning a society that would be technologically advanced in practice but agrarian in organization and values, Wright developed a proposal that embodied the conceptual polarity between nature and culture. This thesis critically examines Wright's resolution ofthis dichotomy in light of the cultural and intellectual currents prevalent in America ofhis time. v CURRICULUM VITAE NAME OF AUTHOR: William R Shaw GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOLS ATTENDED: University of Oregon. -

Frank Lloyd Wright's 1956 Mile-High Skyscraper – the Illinois Peter

Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1956 Mile-High Skyscraper – The Illinois Peter Lobner, 9 May 2020 1. Introduction to the Mile-High Skyscraper On 16 October 1956, architect Frank Lloyd Wright, then 89 years old, unveiled his design for the tallest skyscraper in the world, a remarkable mile-high tripod spire named “The Illinois,” proposed for a site in Chicago. Frank Lloyd Wright. Source: Al Ravenna via Wikipedia Also known as the Illinois Mile-High Tower, Wright’s skyscraper would stand 528 floors and 5,280 feet (1,609 meters) tall plus antenna; more than four times the height of the Empire State Building in New York City, then the tallest skyscraper in the world at 102 floors and 1,250 feet (380 meters) tall plus antenna. At the unveiling of The Illinois at the Sherman House Hotel in Chicago, Wright presented an illustration measuring more than 25 feet (7.6 meters) tall, with the skyscraper drawn at the scale of 1/16 inch to the foot. 1 Frank Lloyd Wright presents The Illinois at the Sherman House Hotel in Chicago on 26 October 1956. Source: IBM.com/blog 2 Basic parameters for The Illinois are listed below: • Floors, above grade level: 528 • Height: o Architectural: 5,280 ft. (1,609.4 m) o To tip of antenna: 5,706 ft. (1,739.2 m) • Number of elevators: 76, divided into five groups, each serving a 100-floor segment of the building, with a single elevator serving only the top floors • Gross floor area (GFA): 18,460,106 ft² (1,715,000 m²) • Number of occupants: 100,000 • Number of parking spaces: 15,000 • Structural material: o Core: Lightweight reinforced concrete and steel o Cantilevered floors: Lightweight reinforced concrete and steel o Tensioned tripod: Steel The Illinois was intended as a mixed-use structure designed to spread urbanization upwards rather than outwards.