The Iranian Mojahedin's Struggle for Legitimacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRAN April 2000

COUNTRY ASSESSMENT - IRAN April 2000 Country Information and Policy Unit I. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information & Policy Unit, Immigration & Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive, nor is it intended to catalogue all human rights violations. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a 6-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum producing countries in the United Kingdom. 1.5 The assessment will be placed on the Internet (http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/ind/cipu1.htm). An electronic copy of the assessment has been made available to the following organisations: Amnesty International UK Immigration Advisory Service Immigration Appellate Authority Immigration Law Practitioners' Association Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants JUSTICE Medical Foundation for the care of Victims of Torture Refugee Council Refugee Legal Centre UN High Commissioner for Refugees CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.6 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.2 -

Whole Day Download the Hansard Record of the Entire Day in PDF Format. PDF File, 1.19

Tuesday Volume 618 20 December 2016 No. 85 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 20 December 2016 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2016 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 1291 20 DECEMBER 2016 1292 Heidi Alexander (Lewisham East) (Lab): In a year House of Commons when the Health Secretary has spent quite a lot of time knocking clinicians, it is good to hear him speak so positively about them. After four years in the job, what Tuesday 20 December 2016 responsibility does he accept for the lack of suitably qualified individuals—not just clinicians—who are prepared The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock to take on the top jobs in the NHS on a permanent basis? PRAYERS Mr Hunt: I will tell the hon. Lady what I take responsibility for: more doctors, more nurses and more funding than ever before in the history of the NHS. We [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] know that the highest standards are often achieved when there is strong clinical leadership. Only 54% of managers in this country are clinicians, compared with Oral Answers to Questions 74% in Canada and 94% in Sweden. That is why it is right that we do everything we can to encourage more clinicians into leadership roles. HEALTH Andrew Selous (South West Bedfordshire) (Con): Does the Secretary of State agree that the clinical leadership involved in the Getting It Right First Time initiative is The Secretary of State was asked— important, not only because it will save £1.5 billion, Clinical Leadership which could be put back into patient care, but because patients will be in less pain and will end up having fewer revision operations, and some will even survive treatment 1. -

IRAN COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

IRAN COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 28 June 2011 IRAN JUNE 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN IRAN FROM 14 MAY TO 21 JUNE Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON IRAN PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 14 MAY AND 21 JUNE Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Maps ...................................................................................................................... 1.04 Iran ..................................................................................................................... 1.04 Tehran ................................................................................................................ 1.05 Calendar ................................................................................................................ 1.06 Public holidays ................................................................................................... 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Pre 1979: Rule of the Shah .................................................................................. 3.01 From 1979 to 1999: Islamic Revolution to first local government elections ... 3.04 From 2000 to 2008: Parliamentary elections -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Hugh Seton-Watson, Nations and States (London, 1982), 5. 2. Ibid., 3. 3. Tom Nairn, The Break-up of Britain (London, 1977), 41–2. 4. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflection on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London, 1983), 15. 5. Ibid., 20. 6. Ibid. 7. Miroslav Hroch, ‘From National Movement to the Fully Formed Nation,’ New Left Review 198 (March/April 1993), 3–20. 8. Ibid., 6–7. 9. Ibid., 18. 10. Seton-Watson, Nations and States, 147–8. 11. Anderson, Imagined Communities, 127. 12. Ibid., 86. 13. Ibid., 102. 14. In the case of Iran, the Belgian constitution was the model for the Iranian constitution with two major adaptations to suit the country’s conditions. There were numerous references to religion and the importance of religious leaders. The constitution also made a point of recognizing the existence of the provincial councils. Ervand Abrahamian, Iran between Two Revolutions (Princeton, NJ, 1982), 90. 15. Peter Laslett, ‘Face-to-Face Society,’ in P. Laslett (ed.), Philosophy, Politics and Society (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1967), 157–84. 16. Anderson, Imagined Communities, 122. 17. Arjun Appadurai, ‘Introduction, Commodities and the Politics of Value,’ in A. Appadurai (ed.), The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspec- tive (Cambridge, 1986), 3–63. 18. Ibid., 9. 19. Luca Anderlini and Hamid Sabourian, ‘Some Notes on the Economics of Barter, Money and Credit,’ in Caroline Humphrey and Stephen Hugh- Jones (eds), Barter, Exchange and Value (Cambridge, 1992), 75–106. 20. Ibid., 89. 21. The principal issue in the rise of Kurdish national awareness is the erosion in the fabric of the Kurdish ‘face-to-face’ society. -

What Do Iranians Think of the MEK?

Volume 3 Numbers 32&33 Date: Feb/Mar 2019 What do Iranians think of the MEK? Ali Alavi March 03 2019: Reporters who talk about the MEK usually want to talk about the politics and the money. They say, for example, that John Bolton supports them, that they get Inside this issue: money from Saudi Arabia, that they want regime change in Iran. What do Iranians think of the 1 Sometimes these reporters even mention Iranians. MEK? IT’S A MISTAKE TO 2, 3 When they do, they say the MEK doesn’t have much support in Iran be- TREAT THE MEK AS A cause of siding with Saddam Hussein in the war that ended in 1988. NORMAL OPPOSITION That’s all. GROUP Female Defectors Of The 3 Maybe they don’t say anything else because they don’t know anything MKO (MEK) In EU Parlia- else. ment. March 8th THE SPECIAL MOMENT 4, 5 Maybe they don’t care what Iranians think of the MEK because they are TO SAY NO TO THE too busy talking about what America wants and what Europe wants from CULT OF RAJAVI (MEK, NCRI, …) Iran. THE MOJAHEDIN-E 6, 7, Iranians have a lot to say about the MEK. KHALQ AREN’T AMERI- 8, 9 CA’S FRIENDS. EVEN IRANIANS WHO HATE Not just inside Iran. THE REGIME DON’T WANT MEK Not just ex-members. INTERNATIONAL LIBER- 10, TY ASSOCIATION, 11 The Iranian opposition outside Iran has its own view of the MEK. MEK’S SO-CALLED CHARITY BREACHES Let’s hear more from Iranians about the MEK. -

Mujahideen-E Khalq (MEK) Dossier

Mujahideen-e Khalq (MEK) Dossier CENTER FOR POLICING TERRORISM “CPT” March 15, 2005 PREPARED BY: NICOLE CAFARELLA FOR THE CENTER FOR POLICING TERRORISM Executive Summary Led by husband and wife Massoud and Maryam Rajavi, the Mujahideen-e Khalq (MEK) is the primary opposition to the Islamic Republic of Iran; its military wing is the National Liberation Army (NLA), and its political arm is the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI). The US State Department designated the MEK as a foreign terrorist organization in 1997, based upon its killing of civilians, although the organization’s opposition to Iran and its democratic leanings have earned it support among some American and European officials. A group of college-educated Iranians who were opposed to the pro-Western Shah in Iran founded the MEK in the 1960s, but the Khomeini excluded the MEK from the new Iranian government due to the organization’s philosophy, a mixture of Marxism and Islamism. The leadership of the MEK fled to France in 1981, and their military infrastructure was transferred to Iraq, where the MEK/NLA began to provide internal security services for Saddam Hussein and the MEK received assistance from Hussein. During Operation Iraqi Freedom, however, Coalition forces bombed the MEK bases in Iraq, in early April of 2003, forcing the MEK to surrender by the middle of April of the same year. Approximately 3,800 members of the MEK, the majority of the organization in Iraq, are confined to Camp Ashraf, their main compound near Baghdad, under the control of the US-led Coalition forces. -

1 Khomeinism Executive Summary: Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini

Khomeinism Executive Summary: Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the country’s first supreme leader, is one of the most influential shapers of radical Islamic thought in the modern era. Khomeini’s Islamist, populist agenda—dubbed “Khomeinism” by scholar Ervand Abrahamian—has radicalized and guided Shiite Islamists both inside and outside Iran. Khomeini’s legacy has directly spawned or influenced major violent extremist organizations, including Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), as well as Lebanese-based terrorist organization and political party Hezbollah, and the more recently formed Iraqi-based Shiite militias, many of which stand accused of carrying out gross human rights violations. (Sources: BBC News, Atlantic, Reuters, Washington Post, Human Rights Watch, Constitution.com) Khomeini’s defining ideology focuses on a variety of themes, including absolute religious authority in government and the rejection of Western interference and influence. Khomeini popularized the Shiite Islamic concept of vilayat-e faqih—which translates to “guardianship of the Islamic jurist”— in order to place all of Iran’s religious and state institutions under the control of a single cleric. Khomeini’s successor, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, relies on Khomeinist ideals to continue his authoritarian domestic policies and support for terrorism abroad. (Sources: Al-Islam, Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic, Ervand Abrahamian, pp. 15-25, Islamic Parliament Research Center, New York Times) More than 25 years after his death, Khomeini’s philosophies and teachings continue to influence all levels of Iran’s political system, including Iran’s legislative and presidential elections. In an interview with Iran’s Press TV, London-based professor of Islamic studies Mohammad Saeid Bahmanpoor said that Khomeini “has become a concept. -

Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region

KURDISTAN RISING? CONSIDERATIONS FOR KURDS, THEIR NEIGHBORS, AND THE REGION Michael Rubin AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region Michael Rubin June 2016 American Enterprise Institute © 2016 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any man- ner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. American Enterprise Institute 1150 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 www.aei.org. Cover image: Grand Millennium Sualimani Hotel in Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan, by Diyar Muhammed, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons. Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Who Are the Kurds? 5 2. Is This Kurdistan’s Moment? 19 3. What Do the Kurds Want? 27 4. What Form of Government Will Kurdistan Embrace? 56 5. Would Kurdistan Have a Viable Economy? 64 6. Would Kurdistan Be a State of Law? 91 7. What Services Would Kurdistan Provide Its Citizens? 101 8. Could Kurdistan Defend Itself Militarily and Diplomatically? 107 9. Does the United States Have a Coherent Kurdistan Policy? 119 Notes 125 Acknowledgments 137 About the Author 139 iii Executive Summary wo decades ago, most US officials would have been hard-pressed Tto place Kurdistan on a map, let alone consider Kurds as allies. Today, Kurds have largely won over Washington. -

Íránská Opozice Za Vlády Mahmúda Ahmadínežáda Případová Studie Národní Rady Íránského Odporu

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA FAKULTA SOCIÁLNÍCH STUDIÍ Katedra mezinárodních vztahů a evropských studií Obor: Mezinárodní vztahy Íránská opozice za vlády Mahmúda Ahmadínežáda Případová studie Národní rady íránského odporu Bakalářská práce Karolína Pawlusová Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Pavel Pšeja, Ph.D UČO: 416684 Obor: MV Imatrikulační ročník: 2012 Brno, 2016 Čestné prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci Íránská opozice za Ahmadínežáda: Případová studie Národní rady íránského odporu vypracovala samostatně za použití uvedených zdrojů. V Brně, 18. 12. 2016 …………………………………. Karolína Pawlusová Poděkování Tímto bych chtěla poděkovat PhDr. Pavlu Pšejovi, Ph.D za odborné rady, trpělivost a vstřícný osobní přístup během konzultací. Anotace Tato bakalářská práce se zabývá íránskou opozicí, konkrétně Národní radou íránského odporu. Cílem práce je zjistit, jakým způsobem probíhala interakce mezi touto organizací a íránským režimem za Ahmadínežádova prezidentství. První část práce je věnována popisu íránského režimu a identifikování základních konfliktů zájmů a hodnot. Na základě Hlaváčkovy definice a typologie opozice v nedemokratických režimech je pak v druhé části Národní rada íránského odporu analyzována ze čtyř různých úhlů, a to v širším kontextu existující íránské opozice let 2005 – 2013. Klíčová slova Írán, NCRI, MKO, MEK, PMOI, Národní rada íránského odporu, Lidoví Mudžahedíni, Ahmadínežád, Rajavi, Nedemokratické režimy, Opozice. Abstract This Bachelor’s thesis handles the Iranian opposition, in more particular the National Council of Resistance of Iran. The goal of this Study is to ascertain in which way the interaction between this organization and the Iranian regime during Ahmadinejad’s Presidency takes place. The first part of the Study is dedicated to describing the Iranian regime and identifying the basic conflicts of values and interests. -

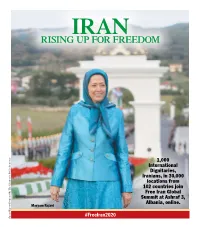

Rising up for Freedom

IRAN RISING UP FOR FREEDOM 1,000 International Dignitaries, Iranians, in 30,000 locations from 102 countries join Free Iran Global Summit at Ashraf 3, Albania, online. Maryam Rajavi #FreeIran2020 Special Report Sponsored The by Alliance Public for Awareness Iranian dissidents rally for regime change in Tehran BY BEN WOLFGANG oppressive government that has ruled Iran from both political parties participating has proven it can’t deliver for its people. tHe WasHInGtOn tImes since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Leaders represented a who’s who list of American “The Iranian people want change, to of the NCRI, which is comprised of multiple “formers,” including former Sen. Joseph I. have democracy, finally to have human Iran’s theocracy is at the weakest point other organizations, say the council has seen Lieberman of Connecticut, former Penn- rights, to finally have economic wealth, of its four-decade history and facing un- its stature grow to the point that Iranian sylvania Gov. Tom Ridge, former Attorney no more hunger. The will of the people precedented challenges from a courageous officials can no longer deny its influence. General Michael Mukasey, retired Marine is much stronger than any oppressive citizenry hungry for freedom, Iranian dis- The NCRI has many American support- Commandant James T. Conway and others. measure of an Iranian regime,” said Martin sidents and prominent U.S. and European ers, including some with close relationships Several current U.S. officials also delivered Patzelt, a member of German Parliament. politicians said Friday at a major interna- to Mr. Trump, such as former New York remarks, including Sen. -

Iran and the Islamic Revolution International Relations 1802Q Brown University Fall 2018

Iran and the Islamic Revolution International Relations 1802Q Brown University Fall 2018 Instructor: Stephen Kinzer Office: Watson Institute, Room 308 Office Hours: Wednesdays 10-12 Email: [email protected] Class Meeting: Wednesdays 3-5:30, Watson Institute 112 Course Description The overthrow of Mohammad Reza Shah in 1979 and the subsequent emergence of the Islamic Republic of Iran shook the Middle East and reshaped global politics. These events have continued to reverberate for four decades, in ways that no one could have predicted. Hostility between the US and Iran has remained almost constant during this period. Yet despite the growing importance of Iran, few Americans know much about the country or its modern history. The shattering events of 1978-80 in Iran unfolded against the backdrop of the previous decades of Iranian history, so knowing that history is essential to understanding what has become known as the Islamic Revolution. Nor can the revolution be appreciated without studying the enormous effects it has had over the last 39 years. This seminar will place the anti-Shah movement and the rise of religious power in the context of Iran's century of modern history. We will conclude by focusing on today's Iran, including the upheaval that followed the 2009 election, the election of a reformist president in 2013, the breakthrough nuclear deal of 2015, and the United States’ withdrawal from the deal three years later. This seminar is unfolding as the United States launches a multi-faceted global campaign against Iran. Given the urgency of this escalating crisis, we will devote a portion of every class to discussion of the past week’s events. -

Iranian Weapons of Mass Destruction

- IRANIAN WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION: THE BROADER STRATEGIC CONTEXT Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy And Adam C. Seitz [email protected] [email protected] Working Draft for Review and Comments: December 5, 2008 Cordesman and Seitz: Iranian Weapons of Mass Destruction 12/8/08 Page ii Table of Contents THE STRATEGIC CONTEXT .................................................................................................................. 1 IRAN‘S CONVENTIONAL AND ASYMMETRIC FORCES .................................................................................. 2 THE IMPACT OF WEAK AND AGING CONVENTIONAL FORCES ..................................................................... 4 The Lingering Impact of Past Defeats .................................................................................................. 4 Resources: The Causes of Iranian Weakness ....................................................................................... 5 Iran and the Regional Conventional Balance ......................................................................................13 IRAN‘S OPTIONS FOR ASYMMETRIC WARFARE ..........................................................................................32 THE INTERACTION BETWEEN WMDS, CONVENTIONAL FORCES, AND FORCES FOR ASYMMETRICAL WARFARE ..................................................................................................................................................32 IRAN‘S ASYMMETRIC WARFIGHTING CAPABILITIES (REAL AND POTENTIAL) ...........................................33